As the city works to integrate its different modal plans — pedestrian, bicycle, freight and transit — into one unified “Seattle transportation plan” in advance of the major update to the Comprehensive Plan in 2024, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is working to clarify when it might create dedicated space for large freight trucks, a mode a number of city policies seek to prioritize but which has no specific dedicated lanes on the city’s streets. With this new policy, the department is adding a new factor to debates over some of the city’s most contested street space.

Seattle’s freight master plan, adopted in 2016, calls for the city to “explore and test the use of truck-only lanes to improve freight,” but until now the department had not developed any framework for that that looks like. Last year, in developing its modal integration policy, SDOT moved in that direction by establishing that freight vehicles should get priority over street improvements for other modes (like pedestrian or bicycle facilities) inside the city’s Manufacturing and Industrial Centers (MICs). Now, a draft policy statement builds on that to more concretely identify where dedicated freight facilities should be considered. The policy statement also includes the concept of large freight vehicles being allowed in transit-only lanes as well.

Dedicated freight-only lanes and transit lanes that allow freight will be considered in locations where they can improve freight mobility and avoid negative impacts to other transportation system users.

-SDOT’s draft freight lane policy statement

One obvious takeaway from the policy statement: it’s very broad and quite vague. The details that will make or break this policy will have to be fleshed out in other places. The fact that freight lanes should “avoid negative impacts to other transportation users” is probably the biggest red flag here: there are lots of ways that reallocating street space, the vast majority of which is currently for general purpose traffic or parking, in order to create dedicated freight lanes could “negatively” impact the users of those lanes. The very instances where freight lanes are going to be most beneficial are when general purpose lanes are already constrained.

Last month, SDOT presented to both the freight and the transit advisory boards, detailing how initial tactics for dedicated space will look at how current and future transit lanes can be modified to accommodate large freight vehicles, creating what are being called Freight and Bus (FAB) lanes. Streets with bus volumes that exceed twenty buses per hour are being ruled out, which would exclude streets like Jackson Street, the Fremont Bridge, and NE Pacific Street.

Current SDOT policy allows people riding bikes to use most of the transit only lanes in the city, but Radcliffe Dacanay, an SDOT planner working on the policy, told the freight advisory board that if large freight vehicles were allowed in transit lanes, signage would have to be changed to prohibit people on bikes from using those lanes as well for safety reasons. Here is another possible repercussion of this new policy: banning people on bikes from a small piece of infrastructure that they may feel comfortable using, with no alternative provided. A bus only lane is not an all-ages-and-abilities bike lane but it’s often better than nothing. Given how often freight is cited when discussing road diets, creating dedicated space for freight, even if shared with transit, should provide a door to providing more walking and biking space, but you likely won’t find any multimodal advocates holding their breath for that.

SDOT moves toward a pilot project by the end of 2022

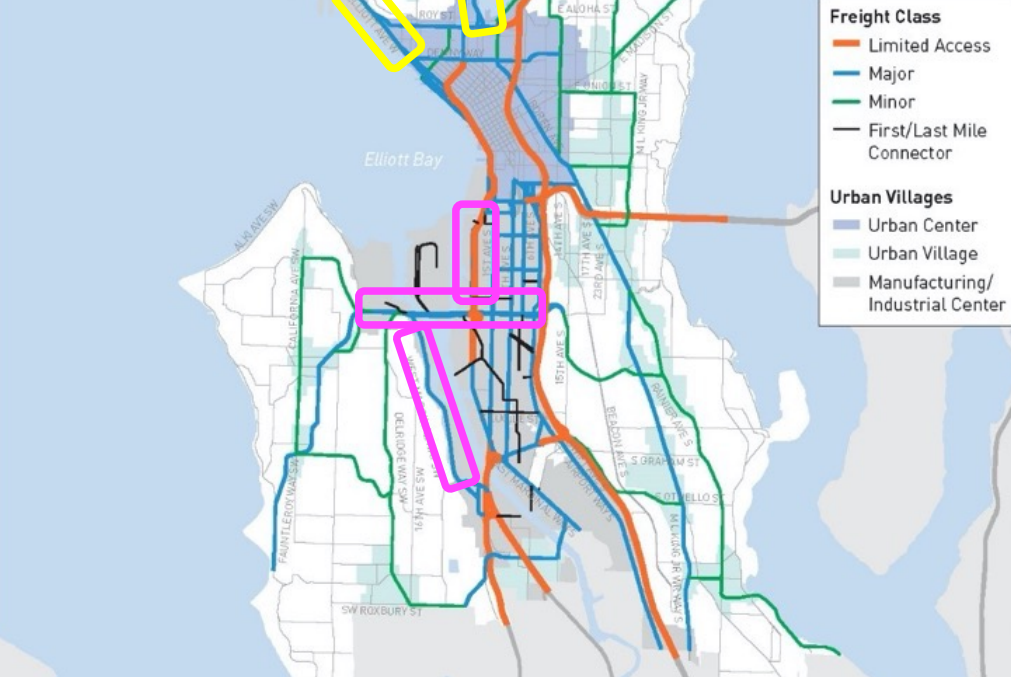

With this framework established, SDOT is moving toward installing a pilot freight only lane, or FAB lane, by the end of this year. Right now we only have a list of some potential candidates, but that list gives us a very good idea of how the department expects the program’s rollout to go. On the north end, on streets that connect to the Ballard Interbay Northend Manufacturing Industrial Center (BIN-MIC), SDOT envisions installing just freight and bus lanes. The streets that have been identified are Aurora Avenue N north of Fremont, 15th Avenue W and Elliott Avenue W in Interbay, and Westlake Avenue N.

Westlake Avenue N is notable on this list because it doesn’t currently have dedicated transit lanes. SDOT is currently moving forward with upgrades to Metro’s Route 40 that would include 24/7 transit lanes along Westlake Avenue, but those plans have run into resistance from the North Seattle Industrial Association. NSIA’s President, Eugene Wasserman, has used overheated rhetoric to argue that all-day bus lanes are a waste of space. Allowing freight vehicles to use these lanes as well could get the department a bit further in getting freight interests in the BINMIC to sign off on the project, but right now it’s too early to tell.

On the other side of town, near the Duwamish Manufacturing and Industrial Center, SDOT is considering freight only lanes, without transit, on three other corridors: East Marginal Way, SW Spokane Street, and West Marginal Way. East Marginal Way is about to get a massive upgrade to make the street better able to accommodate freight traffic, and is a street with many more direct alternatives for general purpose traffic. SW Spokane Street, i.e. the West Seattle low bridge, is currently restricted to freight, transit, and other authorized users with the West Seattle high bridge closed for repair, and it looks like SDOT is exploring what it might look like to keep restrictions for freight in place after the high bridge reopens.

As for West Marginal Way, that street is at the center of another fight over allocating lanes: the freight advisory board has spent months advocating against installing a short segment of protected bike lane in place of an underutilized travel lane to connect the Duwamish Trail. That body has been advocating a rather extreme position that a safety improvement at the Duwamish Longhouse be removed so that the entire corridor goes back to having five lanes. Without doing that, a southbound freight lane is likely not feasible (there are no other lanes), but it’s possible a northbound only bus lane could be considered: SDOT looked at the feasibility of doing so after the West Seattle bridge closed but discarded the idea.

The data supports the separate approaches SDOT is taking on the north and south end: a freight emissions study conducted by the University of Washington showed that 2% of vehicles in Interbay are freight vehicles compared to 5% of vehicles in SODO. Dedicated freight lanes in SODO will likely be more heavily utilized, according to the data.

Will dedicated freight lanes prove effective at being able to keep goods moving through the city as passenger vehicles sit in traffic? If they are, it will be because they will able to be enforced. Seattle currently has special authority to enforce restricted lanes via automatic ticket cameras, but a permanent authorization of that authority is far from certain. Getting freight and industry advocates on board, though, could prove valuable in convincing the legislature to let Seattle keep that authority.

Since freight traffic is currently mostly used as a smokescreen for general traffic, establishing a clear freight lane policy that works well could be a huge first step in clarifying discussions over allocating street space in Seattle. With many elements of SDOT’s proposal modal integration policy problematic, such as the establishing of “critical” streets for people on bikes to use, or the assumption that no street will ever be able to be open to people walking and rolling rather than vehicle traffic, a freight lane policy itself should be absolutely invaluable if developed correctly. But as the department continues to refine the policy, we’ll see how it plays out in practice.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.