Having attended a number of community meetings around Seattle, I can say that there are few things worse than watching a newcomer with ideas get shut down for not having done the reading.

Oh, you didn’t know that there was prerequisite reading necessary to attend community meetings? Yes, in Seattle, there is. While the Seattle Freeze is generally untrue and residents here are genuinely nice and welcoming folk, there is a solid barrier to participating in community groups for established neighborhoods. Joining one of these neighborhood meetings is as close to storming a castle as we can get this side of The Princess Bride.

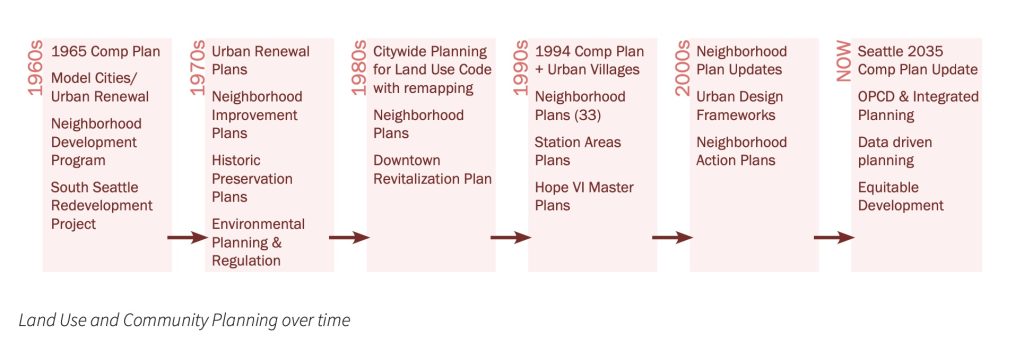

Unfortunately, to get a perspective of what’s being talked about in these meetings and why it’s terrible, we have to go back to the 1990’s when many of these reading lists were established. That’s when neighborhood plans were put in place that devolved many citywide planning issues to neighborhood councils. While the councils themselves are now more or less powerless, most of the plans are still in effect and form the foundation of all the city’s comprehensive planning today. If you have the misfortune of walking into a community meeting as a new resident, the neighborhood’s plan will be quoted at you.

You Oughta Know

In 1994, Seattle approved a Comprehensive Plan that created the Urban Villages across the city. Over the next five years, 33 neighborhoods completed localized plans. Five extras popped up for different purposes. The city maintains links to all 38 of the neighborhood plans on their website here.

Should one choose to review all these documents, there’s a couple things to be found. First, the plans are all different quality scans of the original documents. That makes eight of them unsearchable for important terms. An argument could be made that documents only available as unsearchable PDFs should not be the basis for any contemporary planning, but we’ll leave that there.

Second, there’s 3,544 pages of plans. They range from the relatively brief 23 page Crown Hill/Ballard plan to the hefty 267 page Eastlake Plan.

The searchable documents offer the opportunity to pull out some important words and see what folks were concerned about just before the turn of the 21st century. After toying around with the algorithm to purge some words (mentions of the community itself, street directions, etc) a few repeated words floated to the top.

| Neighborhood Plan | Pages | Date | Character | Process | Traffic | Design | Climate | Equity | Affordab+ |

| Admiral | 90 | December 1998 | 73 | 25 | 60 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Aurora-Licton | 77 | March 1999 | 7 | 21 | 45 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Belltown/Denny Regrade | 69 | December 1998 | |||||||

| BINMIC | 56 | January 1998 | 6 | 28 | 59 | 26 | 2* | 0 | 0 |

| Broadview-Bitter Lake-Haller Lake | 61 | June 1999 | 3 | 9 | 57 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Capitol Hill | 73 | December 1998 | 37 | 16 | 22 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Central Area | 133 | June 1998 | 21 | 27 | 15 | 125 | 0 | 9 | 8 |

| Chinatown-International District | 48 | June 1998 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Columbia City | 86 | February 1999 | 13 | 28 | 32 | 40 | 1* | 0 | 4 |

| Crown Hill/Ballard | 23 | February 1999 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Delridge | 120 | March 1999 | 11 | 33 | 61 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Denny Triangle | 26 | September 1998 | |||||||

| Downtown Commercial Core | 44 | February 1999 | 17 | 13 | 7 | 117 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Downtown Urban Center | 93 | April 1999 | 70 | 22 | 34 | 192 | 2* | 1 | 31 |

| Duwamish | 133 | April 1999 | 24 | 50 | 72 | 44 | 1* | 1 | 0 |

| Eastlake | 267 | January 1999 | 87 | 55 | 11 | 293 | 0 | 4 | 12 |

| First Hill | 45 | November 1998 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 33 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Fremont | 71 | May 1999 | 23 | 61 | 45 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Georgetown | 32 | June 1999 | 9 | 24 | 20 | 80 | 1* | 0 | 10 |

| Green Lake | 136 | January 1999 | |||||||

| Greenwood-Phinney Ridge | 35 | April 1999 | |||||||

| Lake City | 247 | February 1999 | 20 | 22 | 82 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| MLK @ Holly St | 82 | July 1998 | 12 | 101 | 19 | 60 | 2* | 0 | 19 |

| Morgan Junction (MOCA) | 87 | January 1999 | 21 | 42 | 61 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| North Beacon Hill | 87 | March 1999 | 18 | 34 | 32 | 87 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| North Rainier/Mount Baker | 72 | February 1999 | |||||||

| Northgate | 203 | September 1993 | |||||||

| Pike/Pine | 169 | November 1998 | 37 | 21 | 77 | 122 | 0 | 0 | 49 |

| Pioneer Square | 25 | March 1998 | 17 | 25 | 41 | 76 | 2* | 0 | 5 |

| Queen Anne | 166 | June 1998 | 83 | 91 | 38 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Rainier Beach | 88 | March 1999 | 22 | 18 | 25 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Roosevelt | 137 | March 1999 | 43 | 41 | 50 | 148 | 1* | 0 | 10 |

| South Lake Union | 35 | December 1998 | 26 | 11 | 14 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| South Park | 125 | August 1998 | |||||||

| University District | 103 | August 1998 | 27 | 28 | 6 | 96 | 0 | 3 | 21 |

| Wallingford | 101 | September 1998 | 14 | 57 | 110 | 61 | 1* | 3 | 21 |

| West Seattle Junction | 56 | January 1999 | 20 | 25 | 57 | 73 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Westwood Village/Roxhill-Highland Park | 43 | April 1999 |

The plans average 25.6 mentions of the word “character,” 32 mentions of the word “process,” and 39 mentions of “traffic.” The Eastlake plan wins for mentioning character 87 times. But it’s a big document at 267 pages. On a per-page basis among these words, Wallingford wins by mentioning traffic more than once on each of its 101 pages.

By far, the most prolific word was “design.” That showed up on average 77.2 times in each of the searchable plans. The two downtown plans and Pioneer Square featured the word almost three times on each page. Since the search picked up variations of the word, including “designation” as well as the use as a title for a listed staff “designer,” the frequency shows how much emphasis these plans put on categorizing features of the neighborhood and setting rules for the shape of buildings.

On the other side, there are words of importance now but rarely mentioned in these 1990’s documents. First, equity. Only 10 of the plans actually use the word “equity” anywhere, and often only once mentioning “sweat equity” or finance. There are 9 mentions in the Central Area plan due to a proposal for a Community Equity Fund for local development corporations.

Across those thousands of pages, the word “climate” is only mentioned 13 times. Every single one of them uses the phrase “business climate” and nothing in terms of a choking atmosphere. Contrast that with concern about traffic, above.

Lastly, there was actually significant mention of “affordability,” searched in a way to scoop up the most variations on the term. The word was used in 26 of the 30 searchable plans, most often between three to six times. The Capitol Hill plan used it the most frequency, with it appearing on 1/3rd of the pages. However, the plan made several recommendations about “affordable structured parking.” For the plans where it was applied to housing, once could argue that it shows how many of their recommendations failed.

There are quirks like this in each of the neighborhood plans. But there are so many plans that few ever examine them as a whole. And searches like this are only possible by treating these like bags of words rather than rules governing the city’s development. A newcomer doesn’t stand a chance.

I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing

Of course, deep diving into 20 year-old plans is going to turn up questionable recommendations. Twenty years from now folks are going to laugh at how many of today’s plans actually mention vaporware like Hyperloop. In 2042, someone in my position will be like “Haha, they thought vacuum tubes could be built at scale. That ~literally~ sucks. Pass the Tesla icethrower, there’s a heat resistant squirrelfish gnawing on my foot.”

However, neighborhood plans are the basis for all Seattle’s planning work that’s happening now. There is a direct line through the neighborhood plans connecting the 1994 Comprehensive Plan to today. The lineage is literally drawn out in the current 2015 Comprehensive Plan.

For example, take the affordability comment from Capitol Hill. Affordable housing makes it into the neighborhood’s section of the 2015 Comprehensive Plan policies and goals. As part of a diverse community character goal, the plan proposes policy CH-P4: “Strengthen and enhance the character of the major residential neighborhoods and encourage a greater range of housing choice affordable to a broad spectrum of the entire community.” And as part of a diverse housing goal, the plan proposes policy CH-P11: “Seek tools to retain and increase housing affordable to households with incomes at and below the median income.”

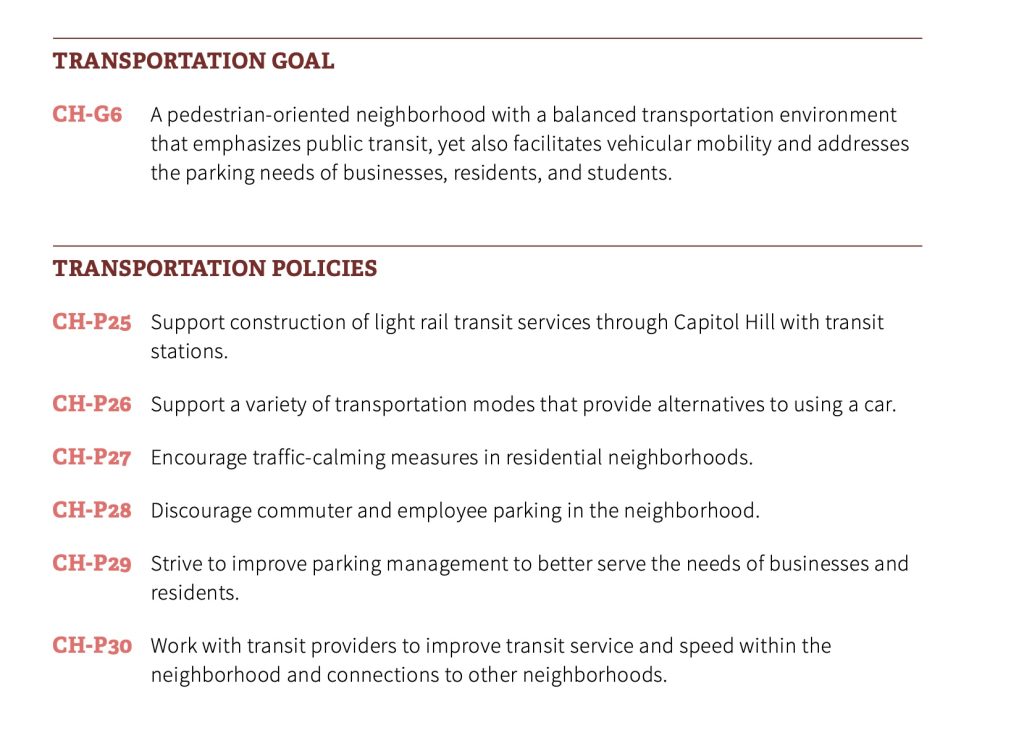

However, the balance of policies is shifted towards the neighborhood’s other affordability concern. Parking is part of the Capitol Hill’s overall transportation goal, which is a level that affordable housing does not achieve. Under that goal, Capitol Hill gets multiple policies about parking. Yes, the policies mention transit, but also give more specifics about affordable parking than affordable housing.

A perspective on this lineage is only available to people who have the time and inclination to actually run down such threads. And this is only one tract through the city’s planning and approval apparatus. Running parallel to the Comp Plan/Neighborhood Plan thread is a parallel line of plans for neighborhood design, with 25 separate plans and the interminable Design Review meetings waiting at the end. There are city-wide plans for cycling, freight transportation, and the often mentioned industrial lands EIS. Each has its own board and/or meeting schedule. Then there are dozens of smaller plans and sketches. And a new Comprehensive Plan is on the horizon.

Seattle’s Department of Neighborhoods (DON) and Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) do admirable, but incomplete, work keeping many of these documents available. DON has a short list of applicable plans on each of their Neighborhood Snapshots. Yes, most plans are online for download. But, as above, many are unsearchable within the document so it’s very difficult to pinpoint an important topic without reading the whole thing.

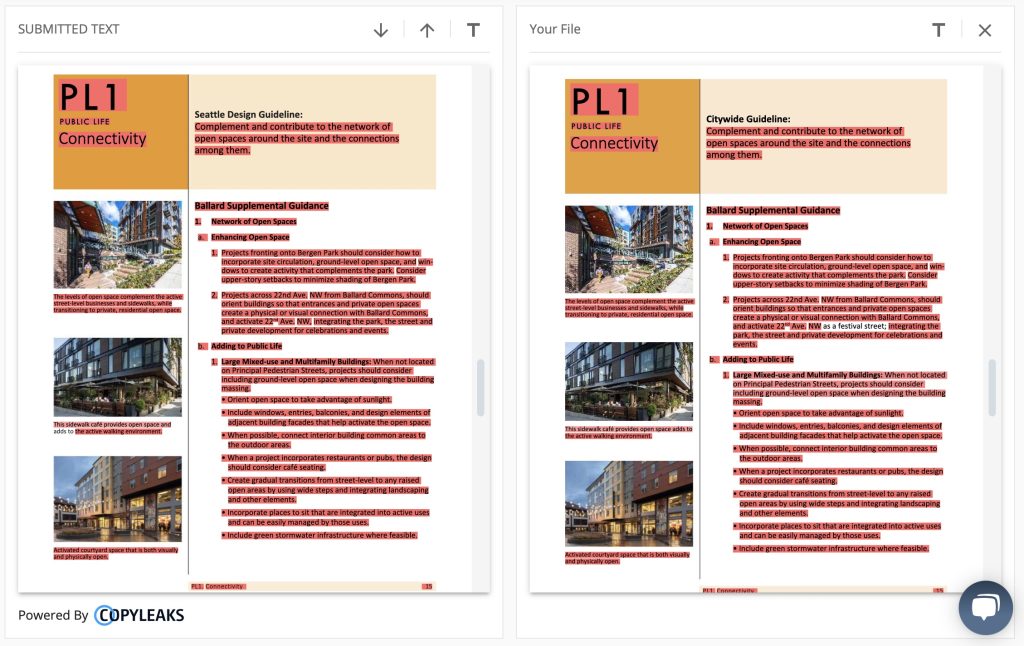

There’s also the problem of getting to the documents in the first place. Google searching for Ballard Urban Design or linking through the Neighborhood Snapshot gets you to the draft of the urban design standards. The official adopted version requires clicking through the Design Review webpage, then navigating to the guidelines tab. Only there is the official adopted version. The differences between the draft and final is small, but somewhat important if dealing with, say, festival streets.

Wonderwall

Besides the technical objections, there’s a very material way these documents prevent public participation. They build walls around each of the neighborhoods. No one reads all these documents, unless, of course, they’re being paid as an architect or planner. But even the pros working on projects in the neighborhoods glean what they need from each document and move on to the next. Few people have the time or expertise to hold a complete picture of the city’s 38 neighborhood plans and the Comp Plan in their heads. Much less the hundred other plans and studies in the city.

Which means that the price of participation on city-wide issues is far too high. The unified city gets shredded to little castles. It’s incredibly difficult to advocate for affordable housing across all the neighborhoods where it’s allowed. It’s virtually impossible to advocate in the other neighborhoods whose local plans are aggressively anti-development. The organizations who try have done immense leg work to build connections with advocates in each neighborhood. Seattle’s a fairly small city, yet needs tour guides for working across neighborhoods. Fiefdom neighborhood plans make the current mayor’s vision of One Seattle a structural impossibility.

Further, having so many outdated plans dilutes the power of the neighborhood plans we need. There are neighborhoods in the city that are suffering displacement. Such diverse neighborhoods don’t get a chance to use the tools of design and public process because other neighborhoods have stolen the resources for themselves. Process displacement and budgetary gentrification, if you will.

The problem with carrying this long library of plans within each neighborhood is that it’s a method of Dead Hand Control, a way of controlling outcomes far into the future. Forcing everyone to do the same reading before participating shuts out far too much of the population. Only those that agree get through the books. The neighborhood plans stop being about improvement, and simply prevent any change outside of boundaries set in the last millennium. Who knows whether your neighborhood will be improved by your great idea. Unless it meets the narrowly defined affordable parking provisions or balcony design rules established while listening to the Spice Girls, too bad.

Neighborhood and community planning is about feedback. It’s about expert planners engaging a diverse community to raise up the issues and concerns that normally get ignored. Perhaps that happened sometime between 1996 through 1999. But since then, the neighborhood plans have been the mechanism used to ignore other issues and concerns. Seattle’s community engagement is suffocating under thousands of pages of documents. Nowhere in those piles of paper is a recipe for climate resilience, affordable housing, or moving the city to an equitable future.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.