Unlike Tesla, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and our state legislature have designed an effective autopilot — an autopilot that, instead of driving cars, drives roadway expansion. The agency justifies large highway projects with claims of reducing congestion, improving safety, or adding pedestrian or multimodal features. These claims and their price tags deserve more scrutiny, but the routes highway projects take to legislative approval are largely free of public process or transparency.

The Washington State Legislature is currently considering a large transportation funding and spending plan. While previous large transportation packages overwhelmingly proposed highway expansion (composing usually 85% or more of packages ranging from $6 billion to $19 billion in 2021 dollars), the Move Ahead Washington package splits transportation spending into thirds allocated between highway spending (expansion, preservation and maintenance), transit, and infrastructure for walking and biking. Previous packages have invested overwhelmingly in highway expansion, despite the ever-growing backlog of road and bridge maintenance needs, as well as the climate and equity imperatives to fund transportation for people who cannot drive and to induce more people to drive less.

As in the past, the highway expansions the state legislature proposes include very little information as to whether they are really necessary or serve the long-term needs of Washingtonians. The proposed SR 18-Issaquah/Hobart Road to Deep Creek-Widening is a case in point. As we found during last spring’s session when we began looking into the proposal, trying to get basic facts about its origin and need required a level of effort unreasonable to expect for anyone but full-time lobbyists — which we are not. The SR 18 expansion has been on autopilot for over a decade, making its way to the highway funding spigot. We did spend that unreasonable amount of time and effort digging up this basic project information. This post lays out what we found using data obtained from the public disclosure request and the questions our findings raise about how highway projects in our state get funded and built. (Throughout this post we link to the relevant files received from the PDR. Full files can be accessed here.)

The current Move Ahead Washington package offers new investments in non-highway transportation because a new revenue source will be available starting in 2023 as a result of last year’s passage of the Climate Commitment Act (CCA). The CCA requires that its revenue be used to reduce carbon emissions. A large fraction is required to go to transportation projects that reduces how much our transportation system worsens climate change. The CCA revenue in the package ($5.41 billion over 16 years) cannot be used to fund highway expansion.

The revenues that can, however, go toward highway expansion include large funding amounts from federal infrastructure bill money ($3.4 billion), an exported fuel tax imposed on fuel exported to states with lower gas taxes ($2.05 billion over 16 years), a one-time transfer from the operating budget ($2 billion) and license plate fees ($1.39 billion). But approximately 36% of non-CCA revenues would go to new and existing highway projects, 21% to fish barrier projects, and 26% to preservation and maintenance.

The Process is Hidden from View

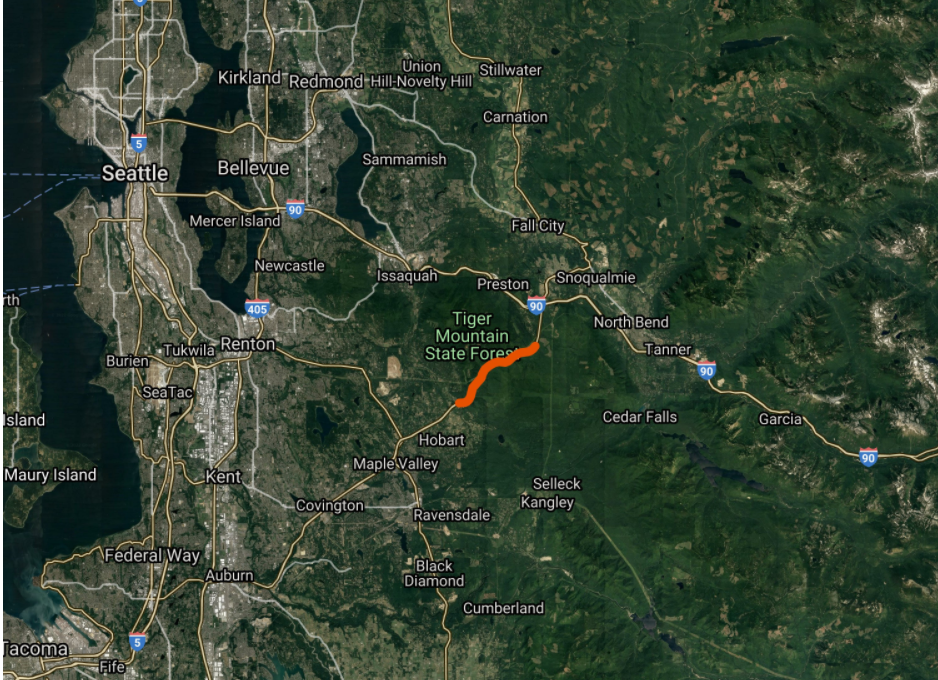

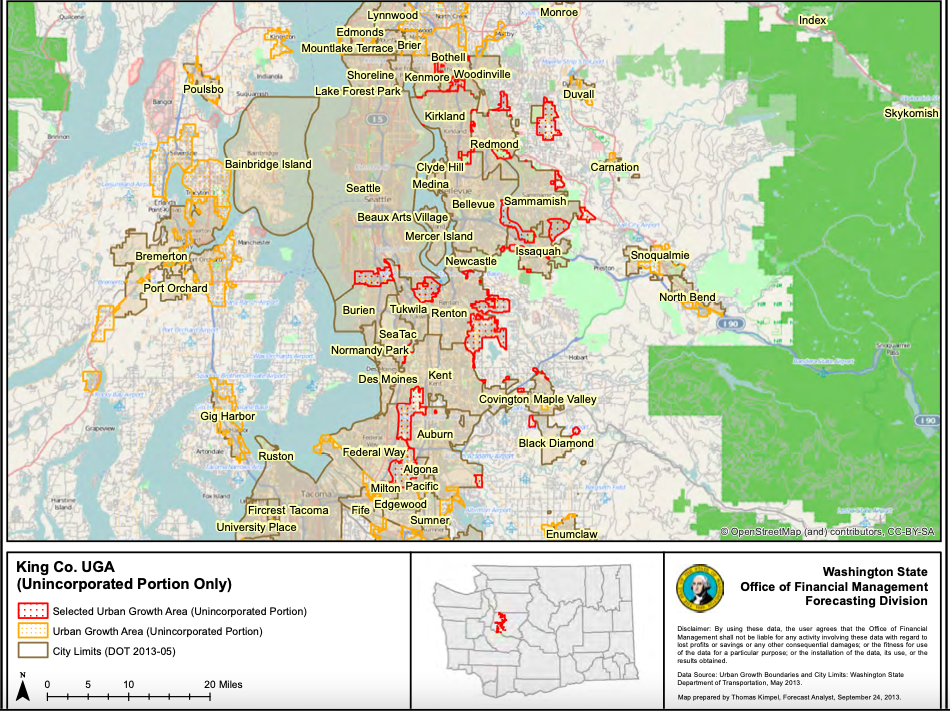

The project area is a five mile section of SR 18 from the Issaquah/Hobart Road to Deep Creek, a couple of miles west of the I-90 interchange. The highway passes by Tiger Mountain State Forest and its popular trailheads but no population centers. Maple Valley, a suburban city of about 28,000, is a few miles southwest of the project area, while Snoqualmie, a city of 14,000, is a few miles northeast. The project website made few details available beyond that the expansion would involve widening the current one lane plus truck-climbing lanes in each direction to two lanes in each direction (keeping the truck lanes on each). Safety improvements and congestion relief were offered as the primary rationale, but the project site did not, and still does not, link to any supporting documentation.

When Rachael e-mailed the project contact requesting that documentation, she was told she would have to submit a public disclosure request (PDR). She almost dropped things there. The PDR process is arcane, not user-friendly for requests that return larger amounts of responsive documents, and despite requiring digital request submissions, only accepts payment for records by check or money order. After narrowing down her initial search terms to a more manageable bill of $91.25 (which started out at thousands of dollars), a full summer of e-mail exchanges with the PDR contact to receive and then download the large numbers of files (around 10,000, although many were not exactly what she had intended to request, like configuration files for vehicle counting software), Rachael was finally ready to dig in.

Before we share what she found, though, let’s raise the first of our questions about how highway expansion autopilot operated in the case of this project:

- Why was the public required to submit PDRs to get basic details about project proposals, and subsequently do the considerable labor in sussing out those details from responsive documents?

- Why is the crash data not on the project website?

- WSDOT believes the crash risk here is too high, but how does it compare to other WSDOT managed roads?

- Why was none of this basic information with supporting documents not posted to a public website by the time of or reasonably in advance of a legislative session in which the project was put forth for funding?

New Decade, Old Claims About Congestion

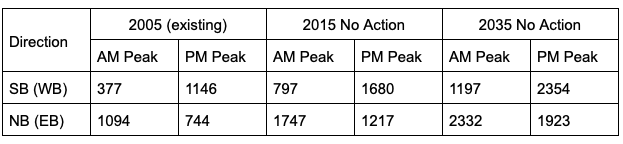

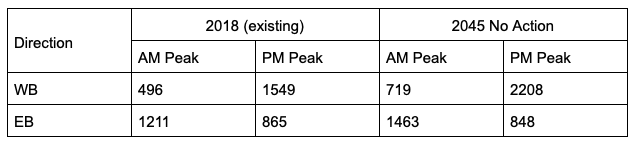

Now we turn to the documents returned by the PDR. Unsurprisingly for a highway project, a lot of work goes into showing current traffic patterns, running them through models and showing disastrous future congestion. The PDR helpfully included data and projections made in 2005 to compare against these current project documents. In brief, the 2005 projections made for 2015 were higher than the actual traffic WSDOT measured in 2018, delegitimizing the claim that the highway needed to be expanded to handle congestion.

This is what they said in 2005:

This is what the current project documents say:

In other documents and several presentations, including one to Washington Secretary of Transportation Roger Millar in February of 2021, WSDOT presents graphics summarizing their peak period congestion data that show most current congestion — near the I-90 and SR 18 interchange — is projected to largely disappear (as a result of the I-90 and SR 18 interchange project set to begin construction this year). The only remaining projected congestion is for 2045 — plenty of time to address transportation needs in other ways than roadway expansion.

This information raises several critical questions:

- Why should we believe WDSOT’s congestion predictions?

- These are peak period numbers; how much congestion during peak hours justifies spending over $100 million per mile?

- Does expanding the roadway through the entire corridor actually solve congestion? Or will it encourage more development with no transportation options other than highways?

- If the worst congestion is projected to be so far in the future (often decades out), could we do something other than expand the highway?

Rachael lives near I-90 and Rainier Avenue in Seattle and has to wait 90 seconds, regardless of time of day, to cross Rainier to get to the northbound bus stop. That’s just one example, too. Neither of us can drive, and we struggle to recall the last time any of the countless delays and insufficiencies of so-called alternative modes of transportation like transit or active transportation and accessible infrastructure were treated with the kind of urgency and financing that highway expansions are offered. About 25% of our state cannot drive and almost 50% of people in the Puget Sound region are not served well by our current car-centric transportation system.

Non-drivers are much more likely to be Black, Indigenous, people of color, immigrants, poor, elders, or disabled, and to live the consequences of climate catastrophe. Spending $100 million a mile to address congestion decades in the future is inequitable and absurd when we are doing so little today to address more pressing transportation needs to provide for development that doesn’t feed the appetite for ever-expanding highways.

This is how seemingly neutral congestion claims drive highway-expansion: a model that always assumes increasing traffic volumes over time will always show (decades in the future) extreme congestion that mandates the need for more road space, even as we ignore or underfund ways to decrease demand.

Safety Is Complicated

The safety claims on the project website were vague, so we looked at the segment’s collision history to understand why widening is seen as a solution. As we saw in the pandemic where many areas saw much lower vehicle traffic volumes, less congestion by itself on a road that is built for more volume can result in more severe crashes.

The SR 18 project area already has climbing lanes in places where one vehicle might get “stuck” behind another. Could widening the roadway lead to more serious crashes because people who speed or otherwise drive recklessly can easily pass other vehicles? WSDOT’s analysis assumes that conflicts occur when the climbing lanes disappear, but there is no information specifically showing a disproportionate number of serious crashes occurring at any single type of location.

Once we dug into our PDR and crash data, we found that project documents’ safety analyses were limited to the years of 2015 to 2019. In that time frame, they note there were two fatalities and six serious injuries crashes. Our separate request for crash data for the twelve-year period of 2008 to 2020, records six fatalities (in five crashes) and ten suspected serious injuries. This is not by Washington State standards a particularly dangerous roadway: SR 99 (Aurora Avenue) in Seattle has at least a three times higher fatality and serious injury crash rate per mile.

What is more concerning about using this safety data to push to expand the roadway is there is little to no evidence that the crashes here are due to congestion or that adding a lane would help. Many documents cite issues at merge points (where climbing lanes start or end), but serious crashes are spread out and not necessarily at these points. Almost all the serious injury and fatality crashes recorded in the 2015 to 2019 data occurred at low congestion time periods.

The 2008 to 2020 data records only two peak-hour fatalities; one of those notes speed as a factor in the crash data, suggesting traffic was not congested at the time. Four of seven recent fatalities noted in this 2018 Living Snoqualmie post about SR 18’s safety record occurred in a significantly shorter stretch of SR 18 between Deep Creek and I-90. Safety improvements for that section of SR 18 are presumably being addressed by the interchange project about to get underway.

Traffic safety engineering rightly focuses on reducing serious injuries and deaths. A fender bender can be jarring, inconvenient, and costly. But when people can walk away from traffic collisions with few to no injuries, that result is our traffic safety system working. Roadway expansion might reduce fender benders during peak hours (at least until induced demand catches up). Is it worth spending $100 million per mile to reduce congestion and fender benders a little while increasing the risk of more serious injuries and fatalities as a result of higher average speeds?

Not being specific about what kinds of crashes happen where and when, or how the proposed changes address them in the long-term, is a way of pushing highway expansion without consideration. There are other ways to improve safety on mostly two-lane highways which WSDOT did consider, including center barriers. But the project team’s preferred center barriers require more roadway width — which is used to justify widening in general. Lower cost and space efficient offerings exist, but widening to two full lanes each way was assumed from the start because previous reports from WSDOT model traffic and safety issues predict increased traffic. During the first round of analysis (Level 1 Screening in WSDOT jargon), they narrowed the possible project down to three alternatives. It’s worth noting that the process started with the assumption of expanding capacity for all motor vehicles (because WSDOT assumes future demand), that assumption remained unquestioned as the process moved ahead, and no option to address safety without expansion was ever considered before arriving at a preferred alternative in November 2020.

Cost and Transparency

The current transportation spending package proposes to spend $640 million on this project. If you’ve followed the news on cost escalations for all kinds of large projects around the state you would look at the previous session’s $500 million and this year’s $640 million and you might assume that increase is mostly related to increased cost projections. You would be wrong.

When this project’s recommended preferred alternative was finalized in late 2020, the cost was estimated at over $800 million, a figure that appears would only have been publicly available as a result of a PDR. The only public cost figure was a $500 million item in the January 2021 budget proposal. The records received do not appear to include direct emails between legislators and the project team about legislative concerns, but emails among the project team in December 2020 and January 2021 show concern about cost escalation from the previous scoping estimate. Subsequent presentations given to Secretary Millar and the project’s advisory group in early 2021 show the team was asked to reduce scope while trying to achieve safety and congestion goals on a smaller budget.

The project website currently reflects a scaling back of the proposal to two lanes in each direction with wider shoulders and no truck climbing lanes. The site provides no information on whether fish-passage or active transportation or transit improvements are part of the current proposal, or how the project specifically addresses safety. Four locations in the project area are part of a 2013 injunction to address fish access. Regional transportation planning and PDR documents claim that the wide shoulders provide non-motorized access. However, given the lack of transparency about the current project elements, it is unclear what, other than expanded capacity, are part of the project.

From a presentation in February 2021, different possible project variations costs were offered:

If the listed safety-only project does have a cost estimate, we have not found it. The original project scoped at the end of 2020 included addressing fish barriers. While the legislative proposal includes $2.4 billion for fish passage work, it is unclear if this SR 18 project includes fish passage work, as the original scope did. Should we be expanding any highway without a firm plan to fix a problem created by that highway? Why is expanding the roadway seemingly a higher priority than meeting a legal injunction?

The documents that discuss scope reductions do not show how these scoped-down projects would address safety meaningfully or how alternate projects that do not expand the roadway could address safety. What exactly is in the project the legislature is considering funding right now, using revenue sources that include significant unrestricted revenue sources such as federal money and operating fund transfer?

What about the other projects?

The current proposed state transportation package has twenty nine other proposed new projects to fund using both restricted funds (the gas tax is a problem) and unrestricted federal and state money. Some of those projects, like the Interstate (more than a) Bridge Replacement program, have slightly more critical attention paid to them. Some projects like the US 2 Trestle Replacement actually have significant public documents on WSDOT’s own website. Other projects listed in the legislative proposal like “SR 3/Gorst Area – Widening” do not even appear to have a WSDOT project page – or at least not one a regular, non-expert resident can find easily.

Suffice it to say it’s hard to understand every project in these huge budget proposals and what WSDOT publishes publicly may not help. We can’t request public records on all of them, nor should we have to. What questions should we be asking before funding highway expansion projects? We submit the following:

- How many crashes and how severe are there? How do they compare to other parts of the state?

- How would widening the roadway reduce serious crashes, including at off peak periods?

- What other transportation modes could better serve this area and how are they funded? (Are they even funded?)

- How much more demand and carbon emissions could a widening project create? The Rocky Mountain Institute has a calculator for this.

- Most importantly: what other projects would not have funding if a particular widening project is funded? Widening projects are increasingly expensive and we continue to fund them faster than we fund maintenance.

The many questions we have raised here should be better answered for the SR 18 widening and all of our state’s large highway projects well before the legislature spends hundreds of millions or billions of dollars in public funds that could be better invested meeting the far more pressing — and far less debatable — needs of Washington residents.