From now until March 2nd, Seattle is taking comments on a proposal to change the zoning rules in the city’s industrial zones. Based on the work of the former mayor’s Industrial and Maritime Strategy group, the changes will address evolving manufacturing and maritime industries while protecting the lands from being gobbled up by big box stores and other commercial uses. As we have covered, you should comment on Environmental Impact Statements because that’s where the city considers the widest array of options before making a decision.

The idea to rezone the city’s industrial lands is a good one. The specifics will be better once fine tuned. The underlying justification needs a lot of help. The Environmental Impact Statement must struggle with the racialized history that formed our industrial areas in the first place.

Updating Industrial Zones For The Future

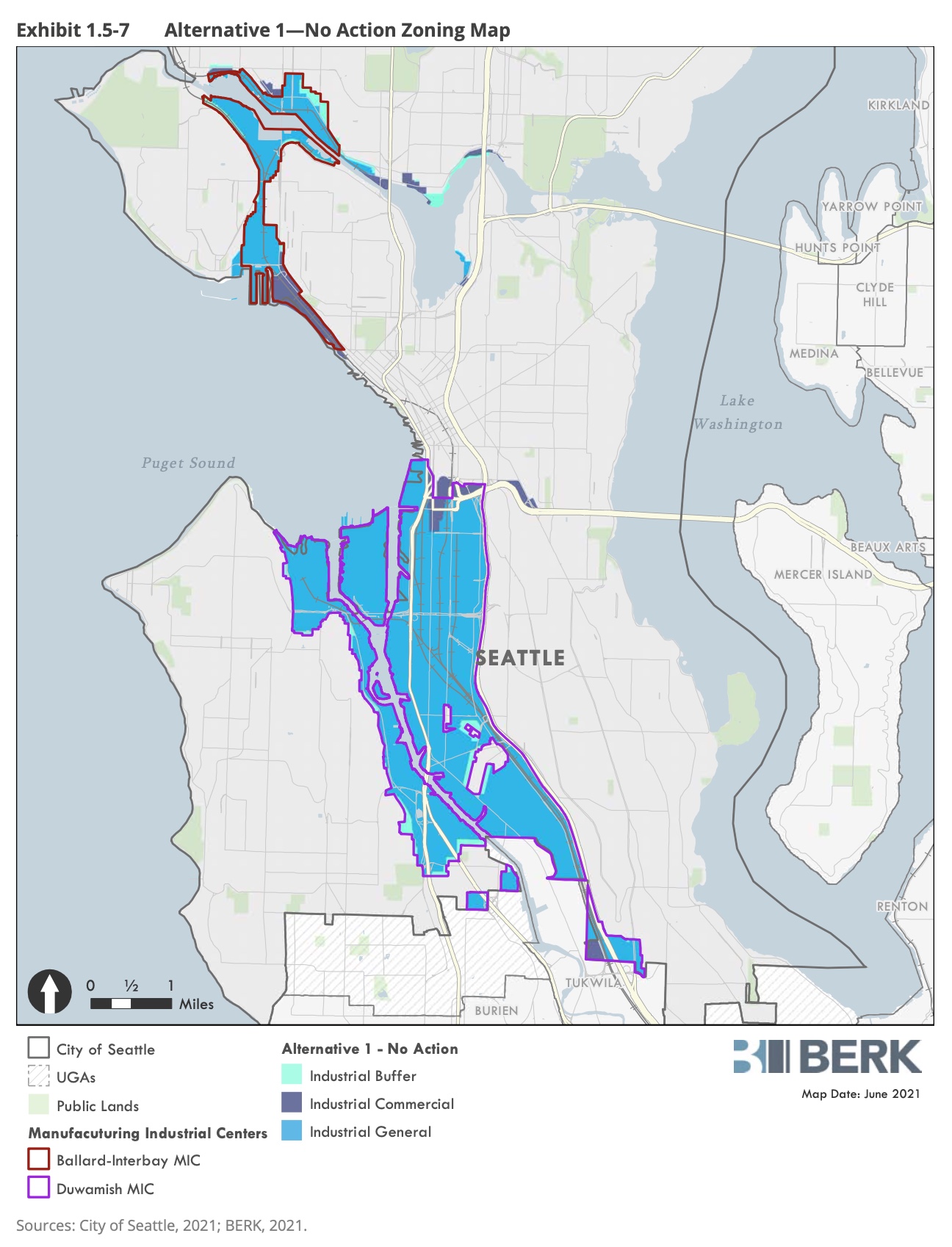

Seattle currently has four industrial zoning designations spread across its two major industrial centers in the Duwamish and Interbay/Ballard. The zones are failing. The general industrial zones are worded so broadly that grocery stores and mini-storage proliferate instead of employers who manufacture things. Car-intensive commercial uses are taking up space next to ports, rail, and vital infrastructure that cannot be moved or replaced.

The three proposed industrial zoning designations recognize the changing needs of industry and its employment role. More importantly, the new zones are established to respect legacy industries, while opening opportunities for new employers with different space needs. These are not soot-spewing coal incinerators of the past, but there’s plenty of allowance for fishing and brewing.

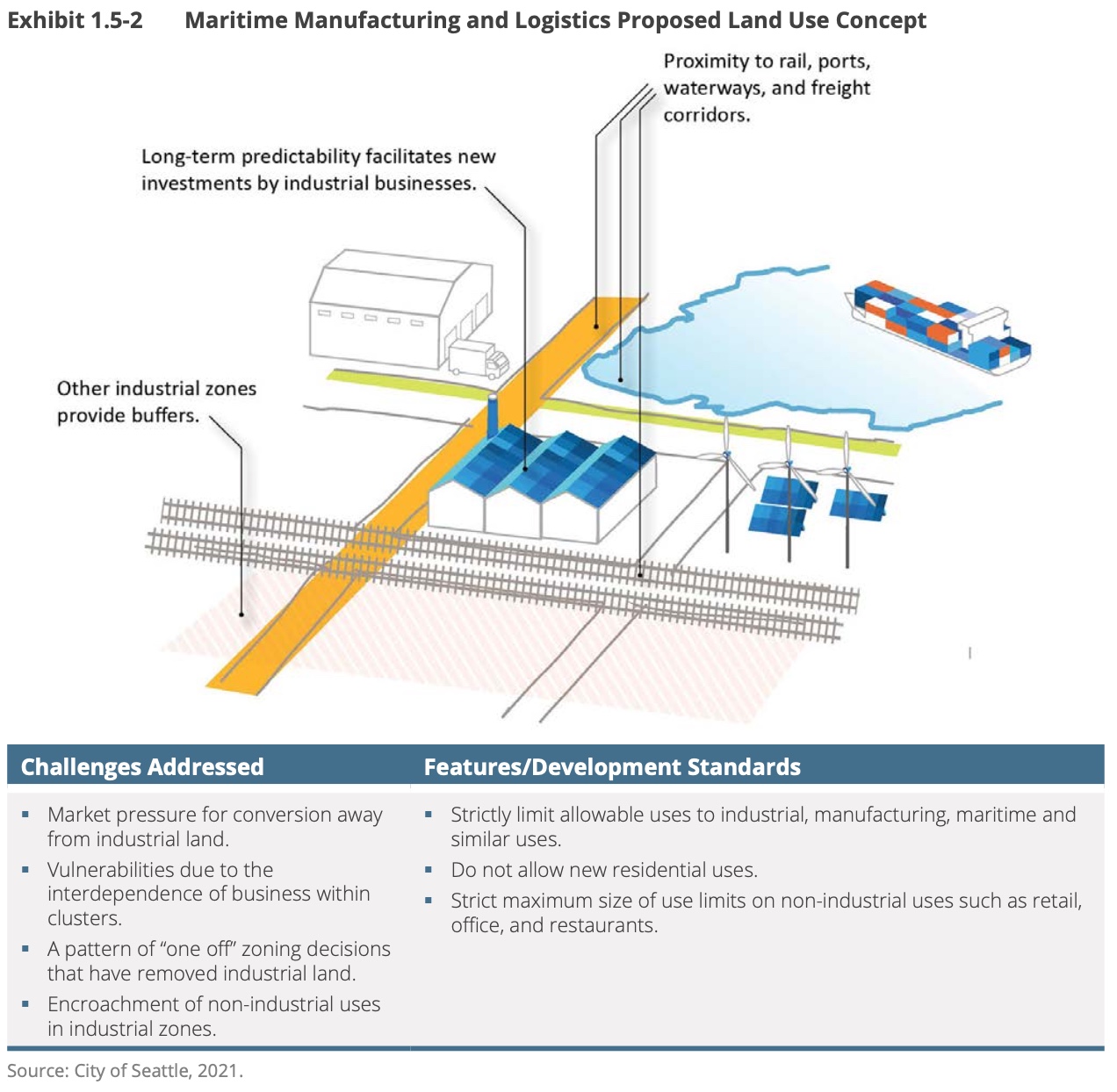

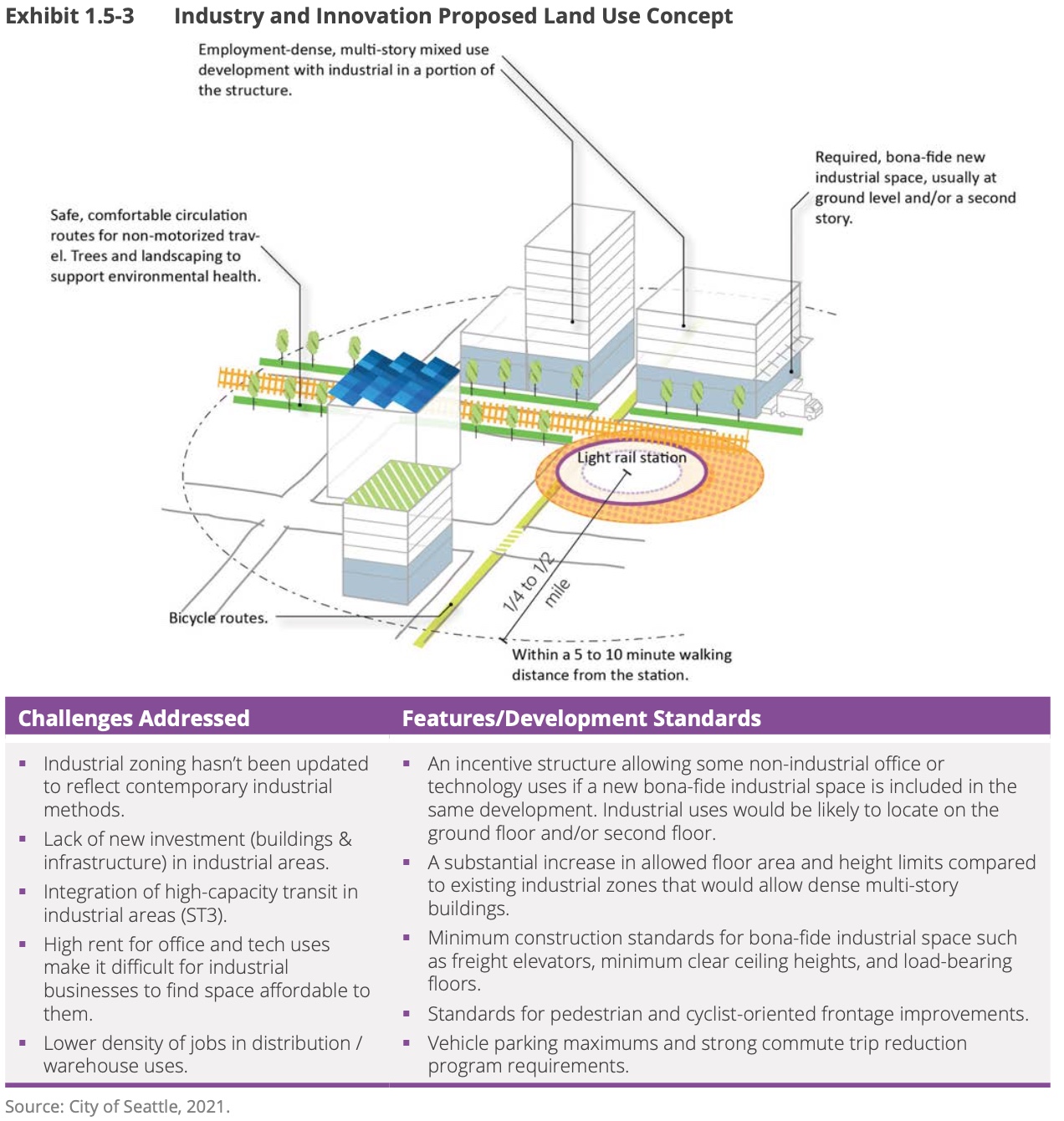

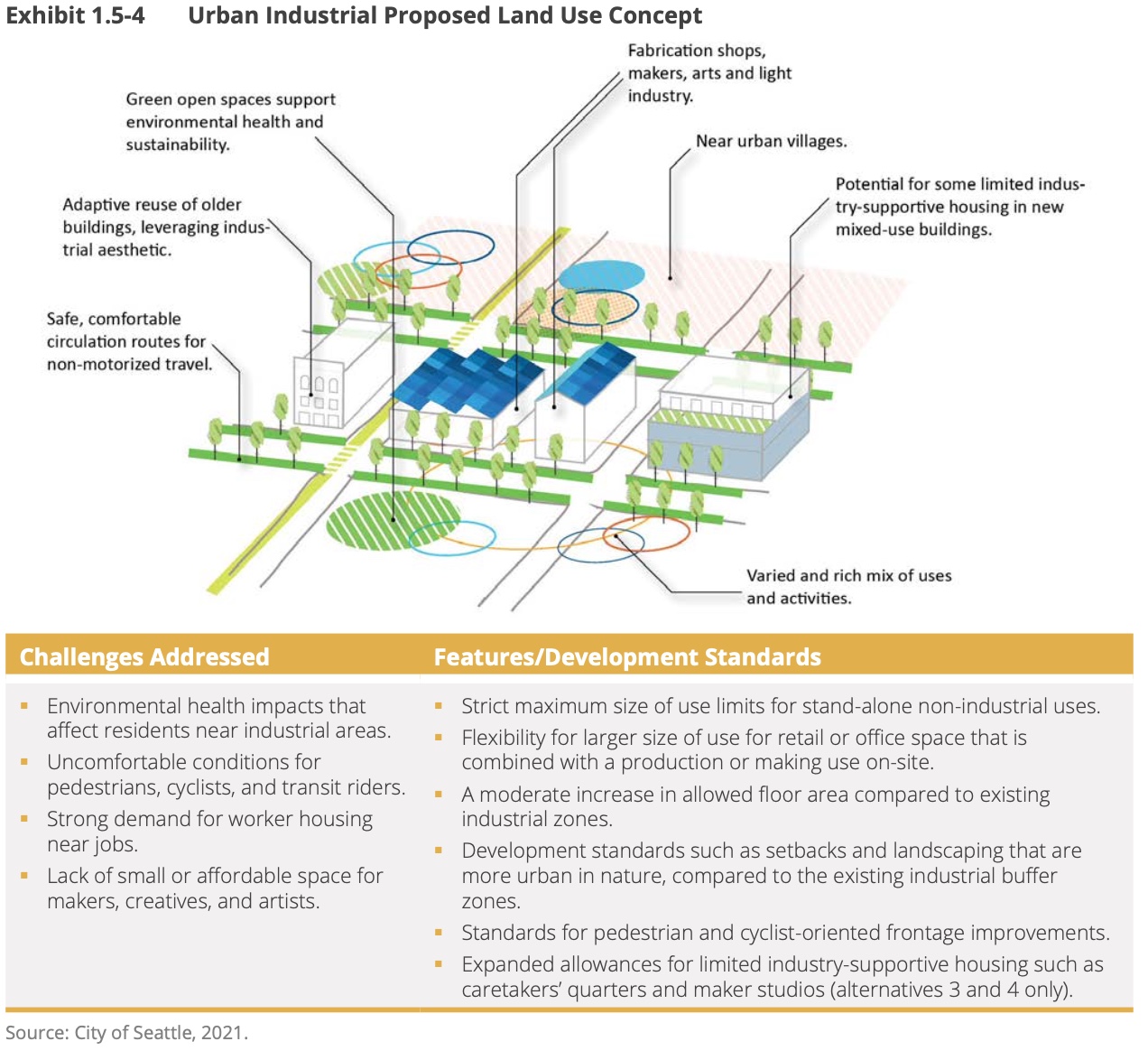

The Manufacturing, Maritime, and Logistics (MML) zone will replace most of the current general industrial zoning, allowing traditional port, warehouse, and manufacturing uses but restricting the retail and commercial uses that are gobbling up space today. The Urban Industrial (UI) zone will be established at the boundaries between industrial areas and urban villages, allowing maker spaces and industry supportive housing. Industrial Innovation (II) zones are for areas around transportation hubs where office and manufacturing can coexist with transit.

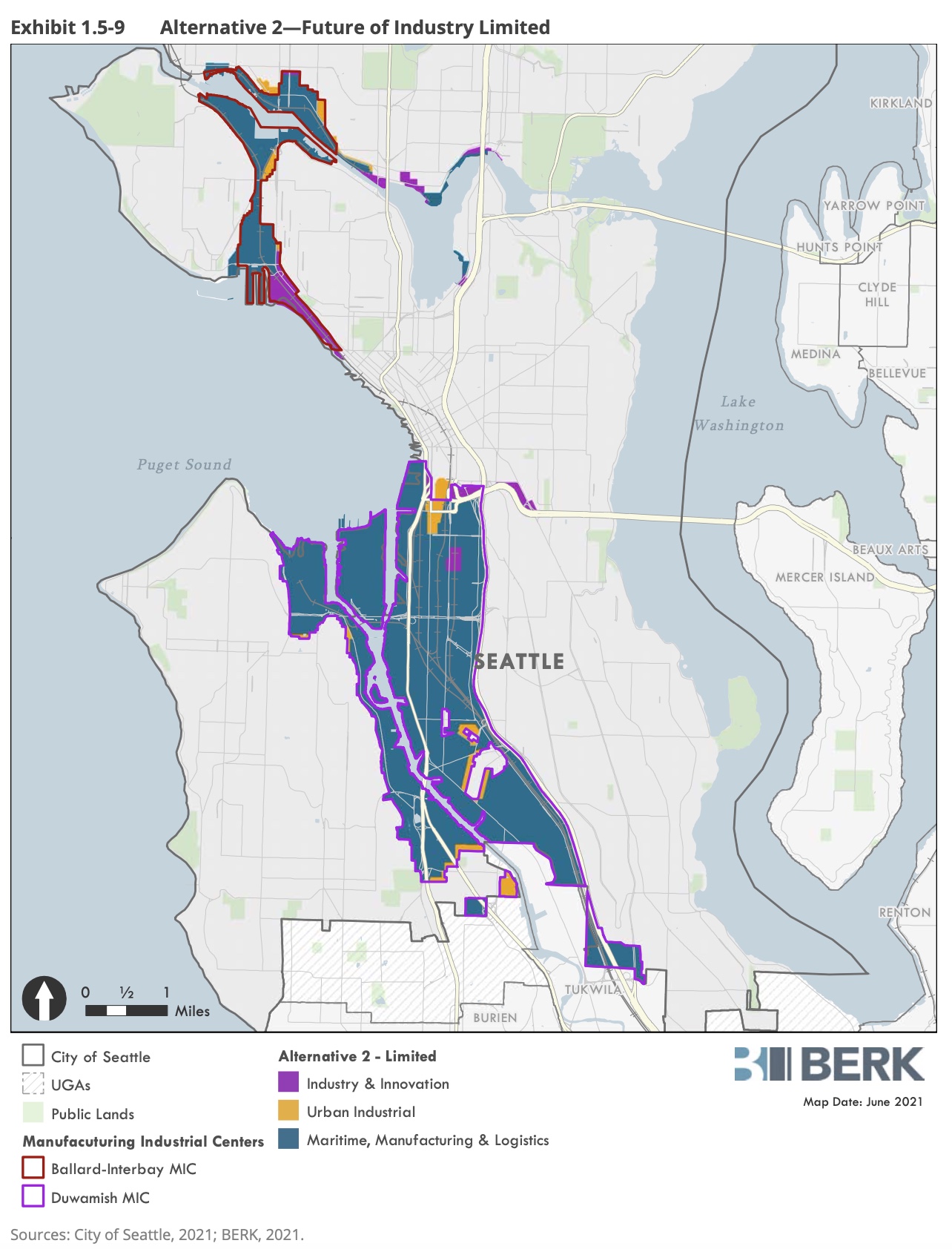

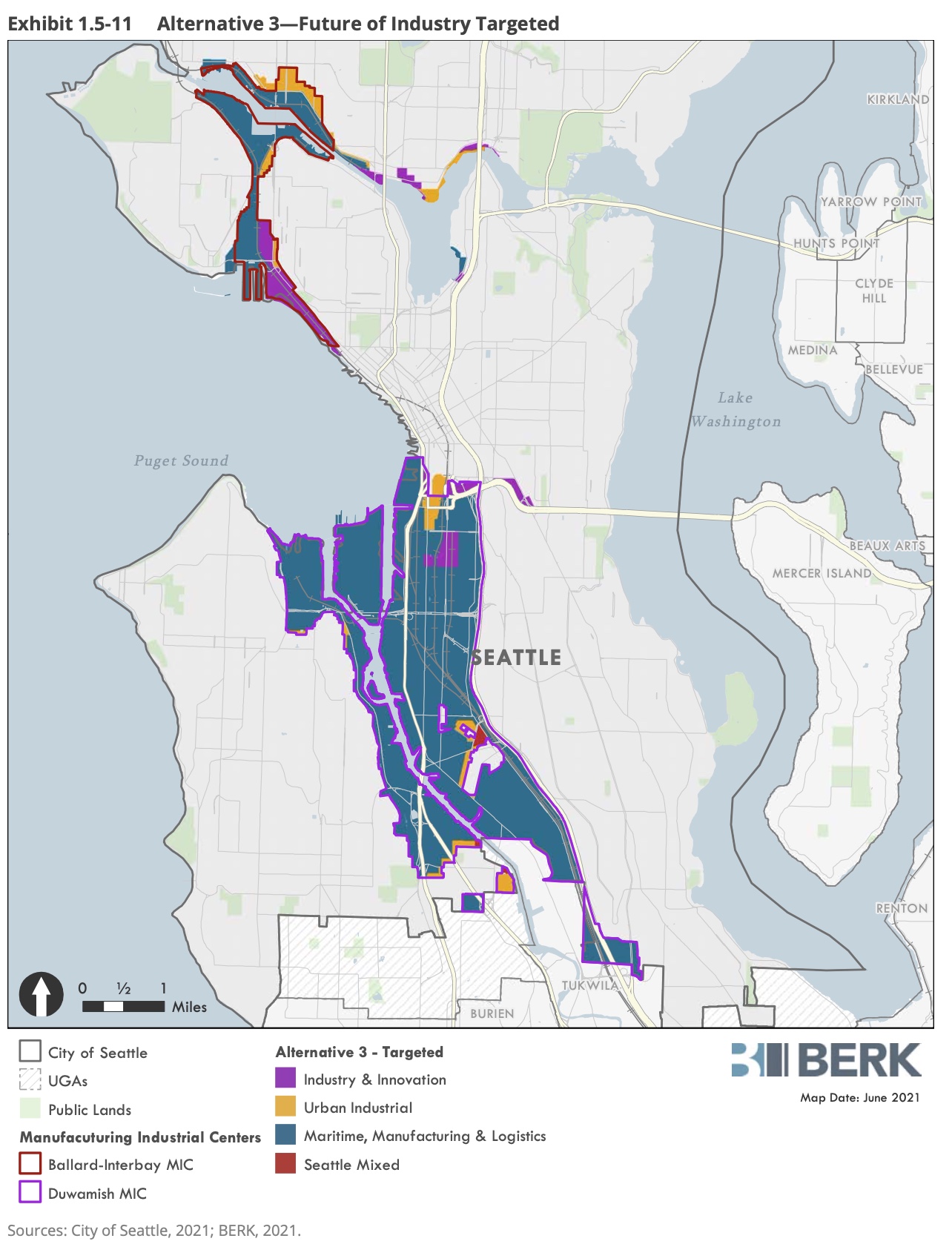

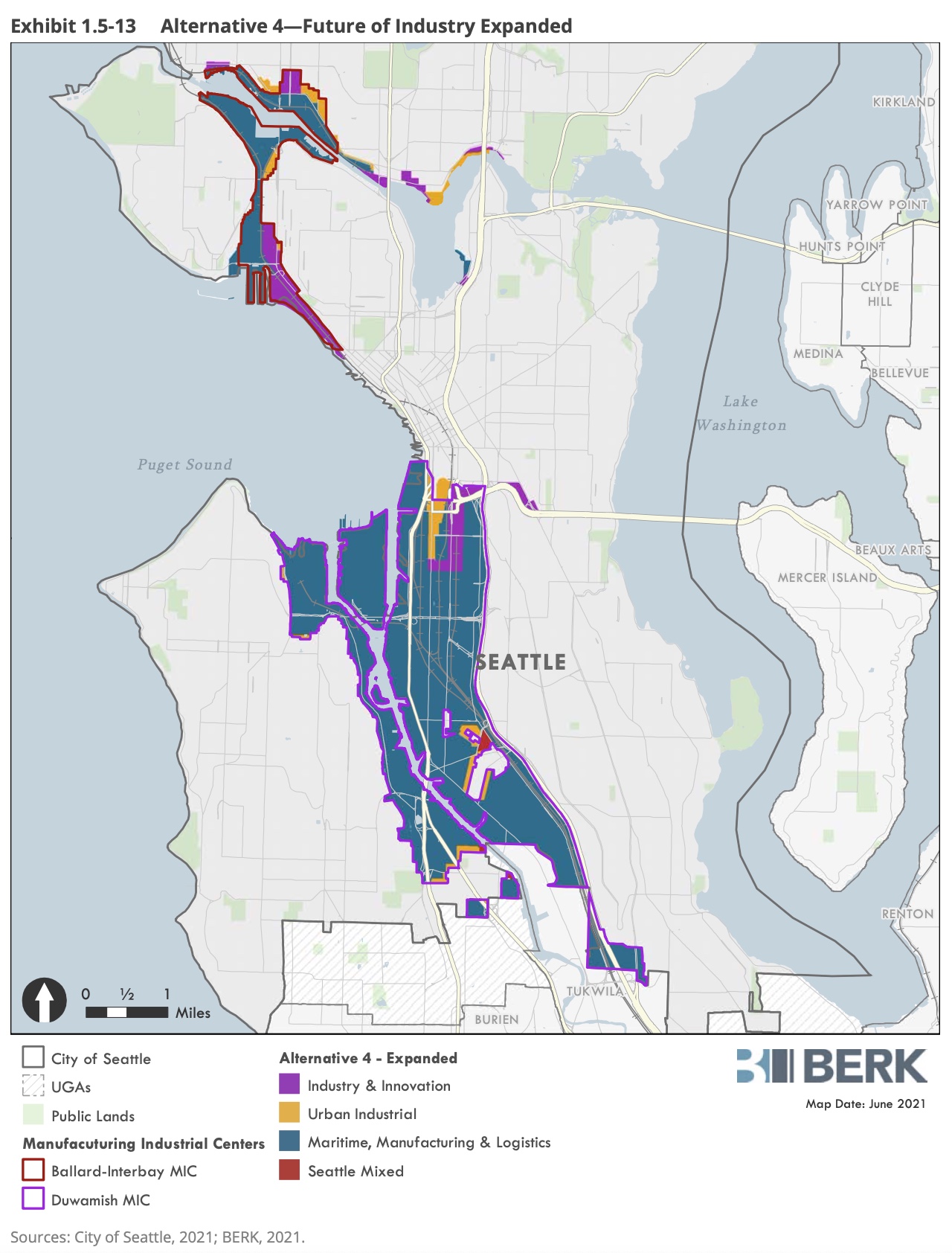

Confusing to many is the fact that the EIS is not about the potential zones. The actual terminology of the new zones is outlined, but specifics are left for the City Council to hash out over the next year. Instead, the EIS examines about how much of the new zones will be laid out across the city’s existing industrial areas. This is a smart way of setting up the EIS because it focuses the discussion on specific locations rather than ephemeral concepts in zoning. The document analyzes four options, each a different mix of the new zones.

As usual and required by law, the first EIS alternative is a “No Action”. This would maintain the existing mix of zones as they are currently written. The remaining three alternatives change the number of acres zoned under each of the II and UI zones. Alternatives 3 and 4 also remove several acres of industrial land in South Park and Georgetown, converting them to Seattle Mixed zoning.

| Description | Alternative 1: No Action | Alternative 2: Future of Industry Limited | Alternative 3: Future of Industry Targeted | Alternative 4: Future of Industry Expanded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maritime Manufacturing and Logistics (MML) | Maintain 90% of area as Industrial General | 89% of area | 86% of area | 86% of area |

| Industry and Innovation (II) | Maintain 5% of area as Industrial Commercial | 5% of area 1/4 mile around transit. | 7% of area 1/2 mile around transit. | 8% of area. 1/2 mile around transit. |

| Urban Industrial (UI) | Maintain 5% of area as Industrial Buffer | 6% of land area. Near transitions. | 7% of land area. Expanded in Ballard. | 6% of land area. Expanded in Stadium district. |

| Housing | Caretaker’s quarters and artist housing. | Caretaker’s quarters and artist housing. | 600 units in UI zones. | 2,000 units in UI zones. |

| Removed areas | None | None | Nodes in Georgetown and South Park. | Nodes in Georgetown and South Park. |

Between Alternatives 2, 3, and 4 the actual variation is very minor. Option 4 offers the most opportunity for new uses near transit. Alternative 3 offers more buffer with urban villages.

As the City Council moves to adopt the new industrial zones and the accompanying zoning map, they will be able to pick and choose between parts of these options. That means the boundaries can end up erratic and narrow due to legislative horse trading. The EIS must do a better job establishing why areas change under each of these Alternatives, and which areas should be treated as a cohesive cluster.

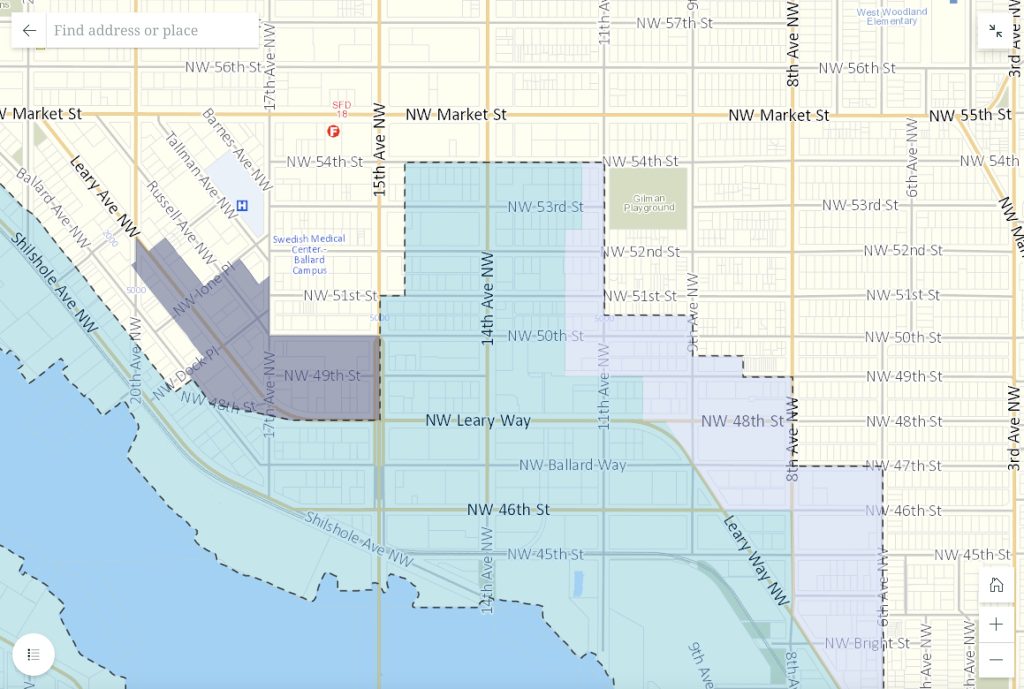

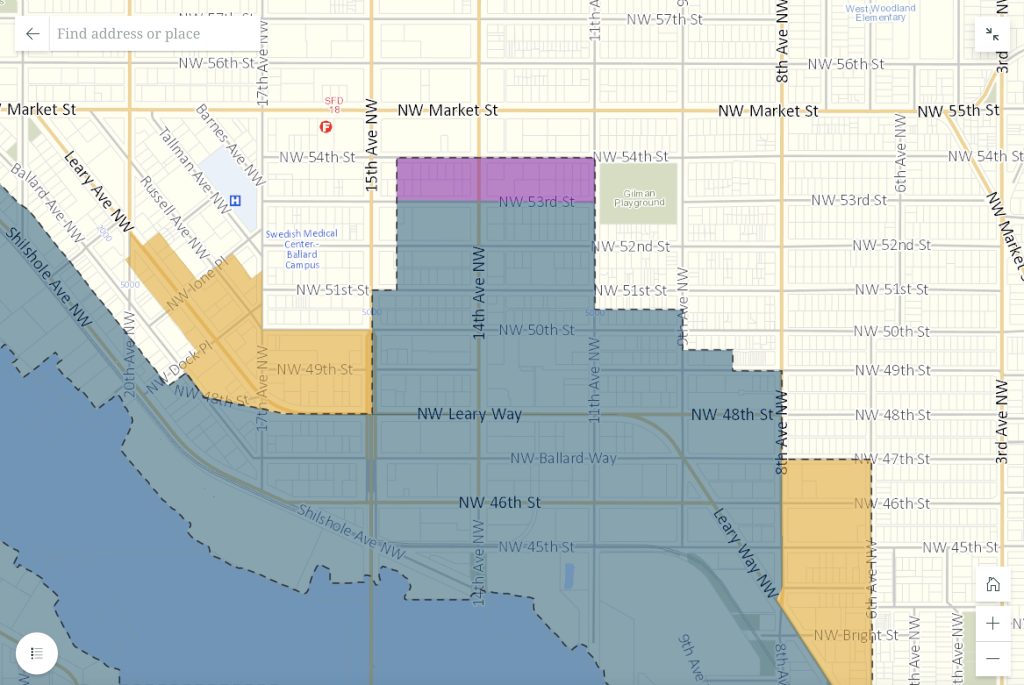

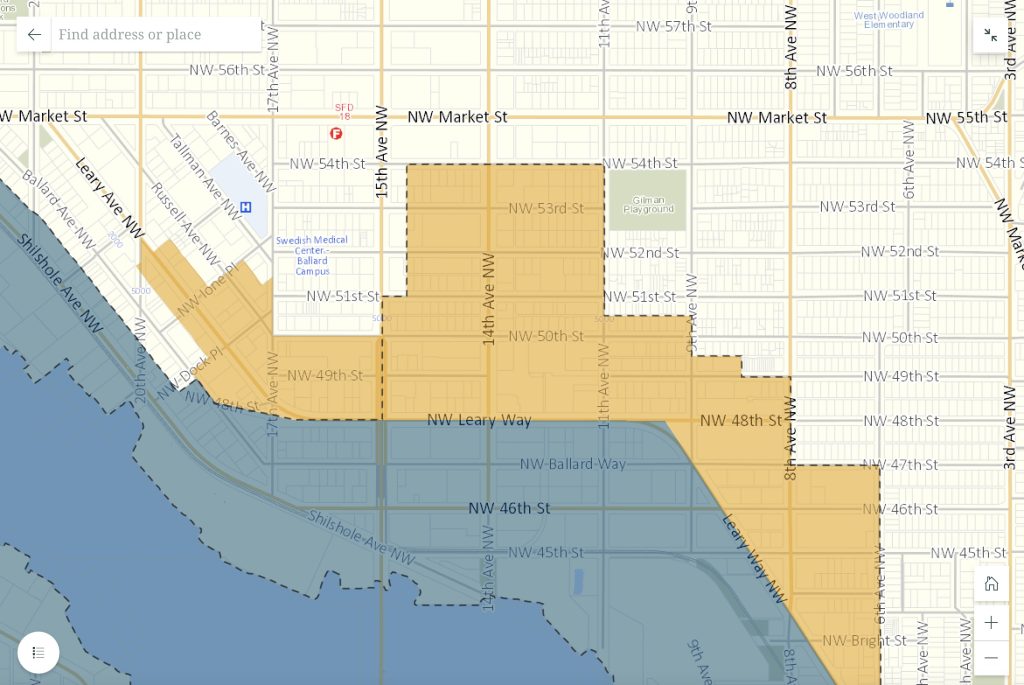

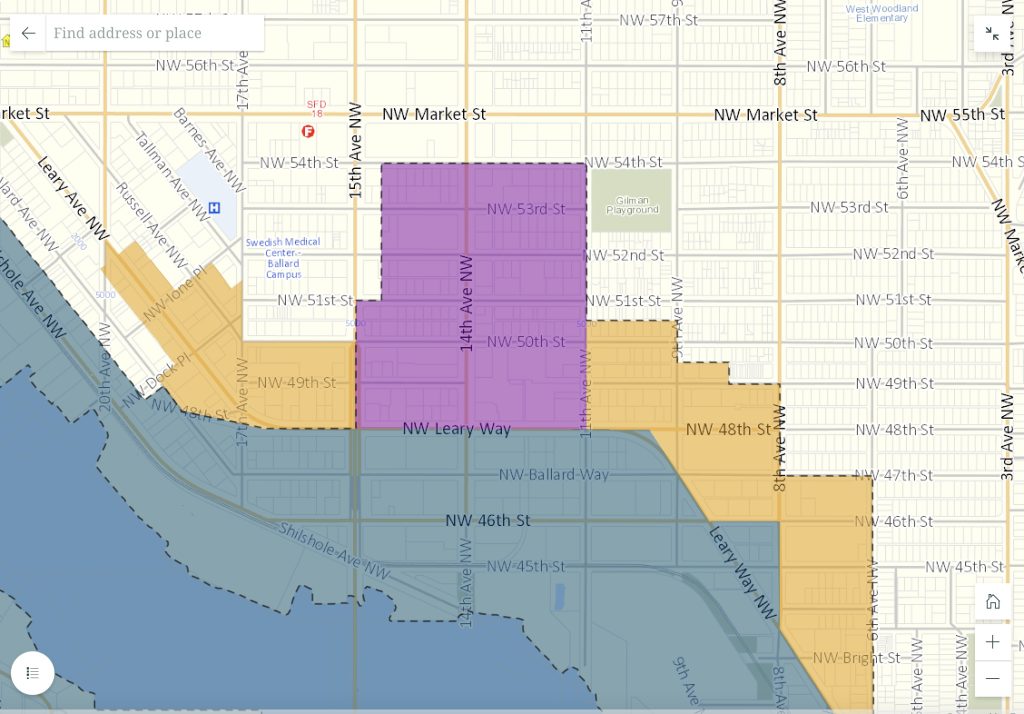

At the neighborhood level, the proposed maps do not offer a picture of cohesiveness. Besides raw acreage or numbers of houses, what does it mean if blocks are divided? Ballard’s Brewery District is a good example. It’s the area north of Leary Avenue on either side of 14th Avenue. Alternative 2 puts it in MML, Alternative 3 in Urban Industrial, and Alternative 4 sets it as Industry and Innovation. But the legislative process can split that apart. The EIS does not strongly justify what is keeping these clusters together.

Speaking of splitting the baby, it must be said that Alternative 1 should be considered a non-starter in its entirety. Even a compromise where some of the current industrial zones are maintained in certain areas should be dismissed completely. The current zoning ordinance is 1,400 unreadable pages. Adding a couple hundred more without removing any of the existing would be idiotic.

While the proposed EIS Alternatives offer needed updates to industrial and manufacturing centers, they are stuffed within the existing boundaries of the current industrial zones. And that’s where we run into a much deeper problem.

Don’t Forget What Concentrated Pollution

It may sound weird to suggest that something is missing from a 700 page document with five appendixes. SDCI staff and consultants have made an extensive analysis of Seattle’s industrial areas across 14 different categories, including land use, public services, geology, and noise. Each of these sections deep dives into the topic and compares possible impacts of each alternative.

But the EIS doesn’t tell the story. Take this paragraph from the Land Use section:

“Historical land use decisions also led to the location of multi-family housing in areas bordering industrial lands that caused environmental justice harms. Seattle’s first zoning ordinance in 1923 and its major update in 1956 located multi-family residential districts at the edges of rail lines, industrial districts, and manufacturing districts. Relatively less affluent renters were exposed to noise and air quality and other impacts, while single family districts removed from the edges of industrial areas were not. The continued pattern of multi-family housing and zoning districts bordering MICs. Continues to be evident today in areas including Interbay and the northeast edge of Ballard.”

While accurate, this obscures two important facts. First, not only were apartments located near industrial areas, but both industrial and multi-family uses were excluded from a vast majority of the city. Second, the pattern isn’t just evident today. It is our city’s current policy.

Between racially restrictive covenants and apartment bans written into zoning, multifamily housing was actively pushed out of many Seattle neighborhoods. Exclusion from the remaining city is important in understanding the issues that the EIS is trying to address. The document lists six emerging factors affecting industrial lands:

- Pressures to convert industrial lands

- Emerging technologies and processes

- Unintended development

- Pending port, transportation, and new industrial building typology

- Environment and climate change

- Equity and accessibility

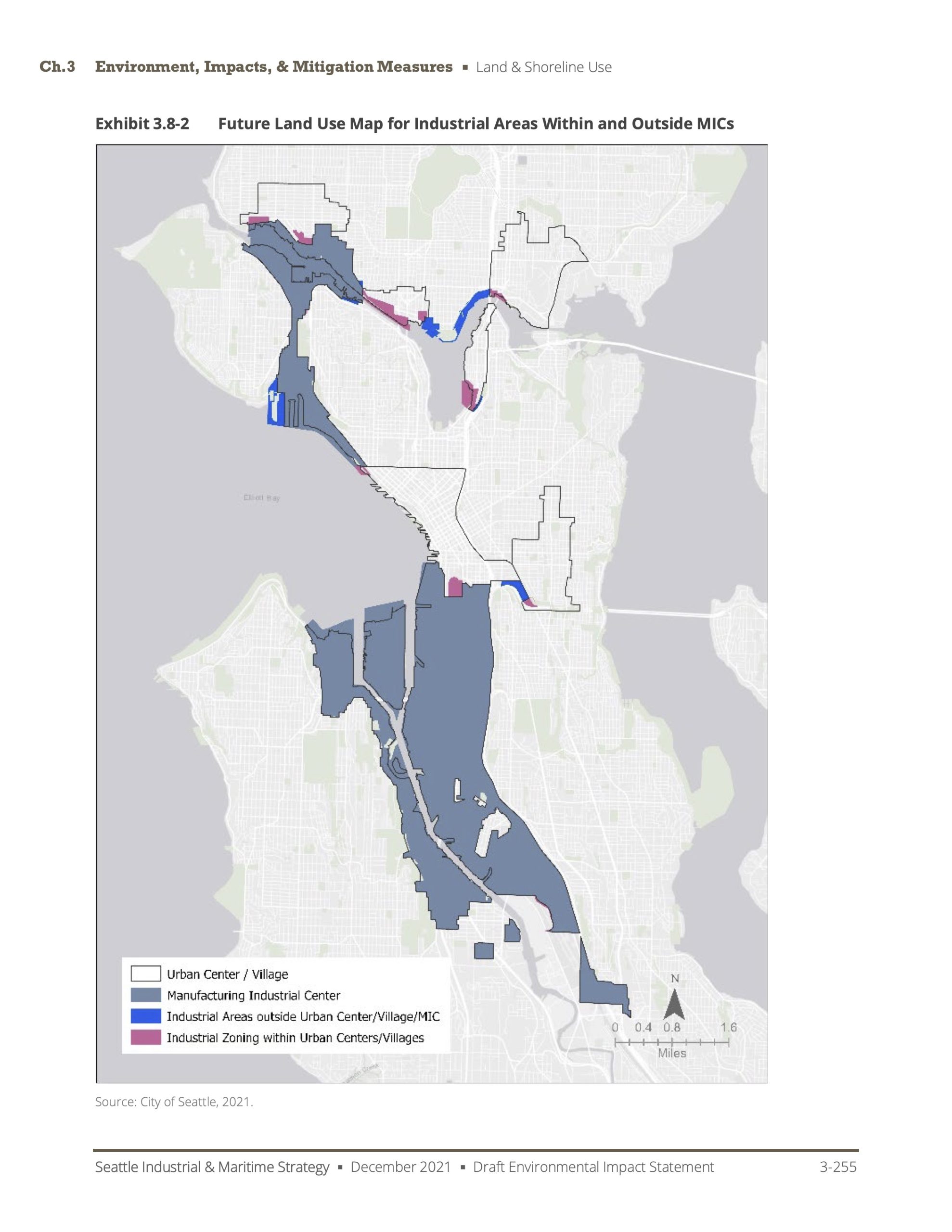

Three of these – conversion pressures, unintended development, and equity – are directly tied to forcing apartments and shops and factories to compete over a small portion of the city’s land. The fourth, Environment and Climate Change, is deeply tied to how pollution is concentrated in small areas and poisoning neighboring communities of color. There is not a map of the entire city in the EIS. They all cut off just above Greenlake. This is a city-wide rezoning of industrial lands, yet it does not show the whole city. To try and develop policies that address land use and zoning issues without once mentioning the other side of the story – the portion of the city devoted exclusively to single-family housing – fails the sniff test.

More broadly, the EIS mentions patterns of exclusion and redlining as if they happened in the past. They are current issues supported by current policy. The EIS did an amazing thing by combining the Urban Villages map with the Industrial Centers map, two that are not normally put together. They show that density never touches water, only industrial waterfront. Beaches are reserved for Seattle’s homeowners.

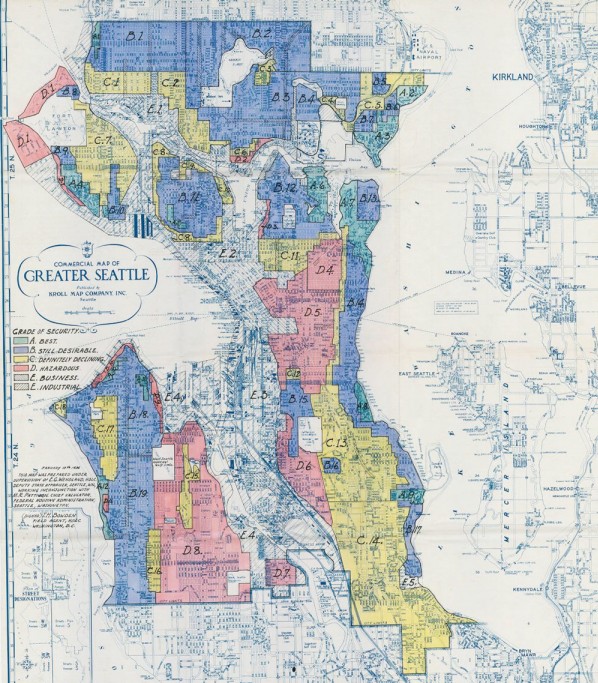

Having this map side-by-side with the 1930’s HOLC maps of redlining shows that nothing has changed in 100 years of Seattle’s zoning. The lines identifying industrial and residential in the 1920s became the boundaries between White and Black mortgagees in the 1930s. Those walls grew taller with restrictive covenants in the 1950’s and then set the routes for highways in the 1960’s. Those freight routes are the basis for the neighborhoods designated as apartment corridors in urban villages and specified manufacturing industrial centers in the 1990’s. It’s the basis for zoning we have today. The EIS states “since MICs were established in 1994, there have not been large-scale alterations to their geographic boundaries.” That same recognition can go back decades earlier.

The EIS struggles to explain how new zones will overcome some of the disparate impacts to communities burdened by the impacts of industry. As extensively documented by the Duwamish River Community Coalition, many of those mitigation measures come down to “new zones will prompt construction of new buildings that will be better.”

Buildings did not concentrate the disparate impacts of pollution and poverty. That was the city specifying factories and manufacturers were only allowed in certain areas that happened to be next to communities of color. The boundaries are the segregation. This EIS maintains each and every one of them.

And that’s the reason it’s vitally important that this story be told within this EIS. There are 100 years of policies squeezed between that first Seattle zoning code in 1923 and today. Each one builds upon the last. Unquestioningly carrying forward the framework of racial segregation and exclusion from one copy to another is just putting a new book cover on the same redlining manual. This EIS fails to recognize that chain, much less break it.

You Get A Say

In our explainer about Environmental Impact Statements, we suggest that there are two important things to look out for when reading an EIS: Does the EIS present information that contradicts something we know? And does the EIS make a “decision before the decision” by dismissing options for no reason?

For the Industrial Zones, there has been a decision made that the city and its residents don’t get a say about. That decision was to stick with the current, segregationist boundaries around industrial zones. The EIS proposes a city-wide zoning decision, without looking at the city as a whole.

DRCC’s list of comments is extensive. Please boost them, add your personal interests, and send them by email or storymap link to SDCI by March 2nd. Here are a few more potential additions to the EIS that may be useful for your comments, if the spirit moves you:

- Add documentation, analysis, and maps that connect Seattle’s historic segregation, redlining, and exclusion to the present day location of industrial uses.

- Complete a city-wide analysis of zoning that looks specifically at the ways commercial and multi-family exclusions in other parts of the city leads to the competition for industrial land.

- Examine which recommendations and boundaries are carried over from older plans that have never been vetted for equity or impact, including transportation and public facilities.

- Specify which groups of zoning changes within each alternative should be treated as divisible or as a cluster/group and describe why.

These criticisms do not try to blow the entire Industrial and Maritime EIS out of the water. As said, the proposal to update the city’s industrial zoning is good. The proposed zones have a lot of potential to reflect the new realities of manufacturing. They offer a chance for employers to be good neighbors to the transit and neighbors. The actual locations and minutiae of the zones themselves will require attention to prevent drafting in all sorts of petty, classist, or biased exceptions. But the proposal is strong and having it on the table is a massive step forward.

What is missing is a level of self-awareness. These historical boundaries made their own problems, and we’re left to unquestioningly continue being constrained within them. Environmental Impact Statements should make robust efforts to understand history and the sources of inequity in shaping land use decisions. Without those components, the City will set itself up for unlimited challenges as it moves ahead with this rezoning and the coming 2024 Comprehensive Plan.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.