The failure of the City of Seattle to achieve its long-envisioned goal of creating a trail along Shilshole Avenue in Ballard to complete the “Missing Link” in the Burke-Gilman Trail has been going on for so long it has become a running joke. It was recently made into a Valentine by The Seattle Times, even. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) now says they hope to complete the approximately one mile of trail by 2024, just as the nine-year Levy to Move Seattle is expiring. If that’s true, it will be the culmination of a project that officially started in 2008 with the environmental review of a trail along Shilshole and Market Street, but which in reality goes back decades.

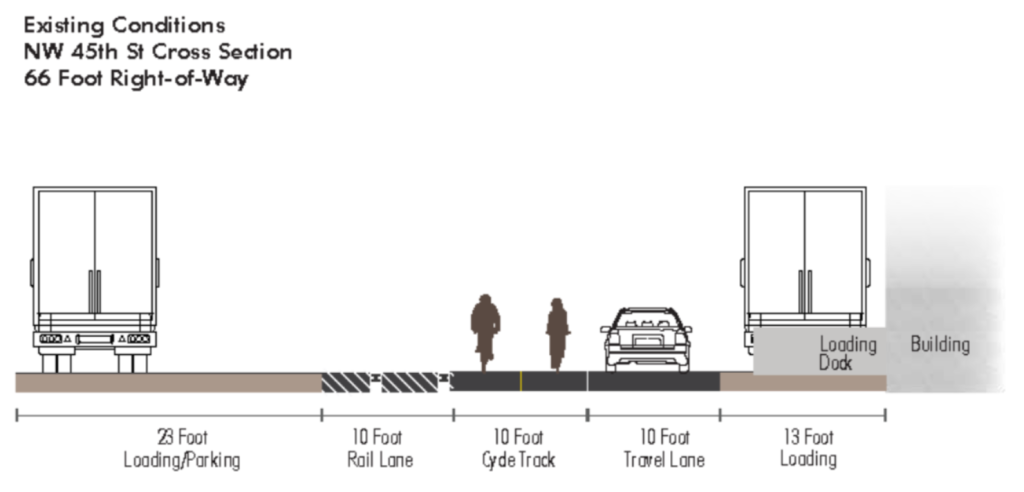

In the meantime, though, the path that people biking use today underneath the Ballard Bridge, where a two-way bike lane crosses a portion of railway maintained by the Ballard Terminal Railroad, is still incredibly dangerous.

“We acknowledge that multiple and ongoing legal challenges by industrial opponents have prevented the City from completing the Burke-Gilman Trail in this portion of the Missing Link,” Rob Levin, an attorney with the firm Washington Bike Law, told me. “But the City still has a duty to make this street reasonably safe for travel by bicycle.” Levin’s firm is preparing a lawsuit to push the city and the Ballard Terminal Railroad to take action before anyone else is hurt, regardless of the timeline for the permanent trail’s completion.

Something unusual about these particular railroad tracks is that the City is indemnified against lawsuits regarding the operation of the railway. In 1997, BSNF, which had operated in Ballard, ceased operations on Shilshole. Ballard Terminal Railroad was created to provide rail service to businesses in the area, and a franchise ordinance signed that year notes that Ballard Terminal Railroad “shall defend,…and shall fully indemnify and hold the City and its officers, employees, and agents harmless from any and all losses, claims, actions, judgments, property damages, death, personal injuries, or damages suffered by any person or entity” in the railroad right of way, even if the City or city employees were found partially responsible.

Levin argues that the 1997 agreement has removed the sense of urgency that might otherwise exist at this location if the danger was the city’s responsibility to fix. “It feels as though that agreement may have removed the financial incentive that tort claims typically provide to take action to prevent future serious injuries or deaths,” he said. Just last July, someone on a bike crashed on the tracks, suffering a severe concussion and fractures to their face and wrist. Upon receiving a claim for damages, the city forwarded it to the Ballard Terminal Railroad.

That doesn’t mean the City of Seattle has left the area completely alone. In 2014, a two-way bikeway was installed intended to give people on bikes a safe path over the railroad tracks. Before that time, people on bikes were expected to follow arrows to cross the tracks at a right angle. But that didn’t stop the crashes. The continued frequency of those crashes pushed the city to take additional action, but it was slow to act: between 2015 and 2020 the Seattle Fire Department responded to at least 39 incidents of people on bikes crashing on the tracks. At least nine of the people involved in those crashes are being represented by Levin.

In late 2020, the City made further adjustments to the area, refreshing the paint and adding additional plastic posts and signage to direct riders. Those improvements may have been enough to prevent some of the crashes, but Levin and other advocates argue they still aren’t adequate. During a visit to the site earlier this year, Levin pointed out how the design doesn’t take into account how people on bikes would actually use the facility, and leaves little margin for error.

One solution could be flangeway gap fillers, which are rubber or polymer strips installed in the gap of a railway bed that still enable railway operation but which make it harder for a bike tire to get stuck in a track gap. In 2018, the City of Seattle settled with the family of Desiree McCloud following a fatal crash involving the tracks of the First Hill Streetcar in 2016. In a 2018 deposition for the case, SDOT project manager Jessica Murphy, who worked on the streetcar project, disclosed the dangers posed by railroad tracks for people on bikes, but argued that flangeway gap fillers were more appropriate for heavy rail lines with low speed traffic, making them exactly the right fit for the Missing Link’s tracks.

SDOT has been told for years that flangeway gap fillers could be the right fit here. But installing them likely requires cooperation of the railway. Ballard Terminal Railroad does not appear to be interested in systemic changes at this location to keep people safe, and Levin says he isn’t aware of a single action that Ballard Terminal Railroad has taken in the last twenty years to make conditions safer for people on bikes. Ballard Terminal Railroad is also a part of the coalition that has been fighting the Shilshole alignment for the completed trail in court for many years now. If changes are to happen, they will likely have to be entirely city-led.

In the meantime, Levin said he is sad and angry that inexpensive fixes that would have prevented serious injury haven’t been done here. “We can’t wait for the Missing Link to be solved in another year or ten,” he said. “We need this street to be safe now.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.