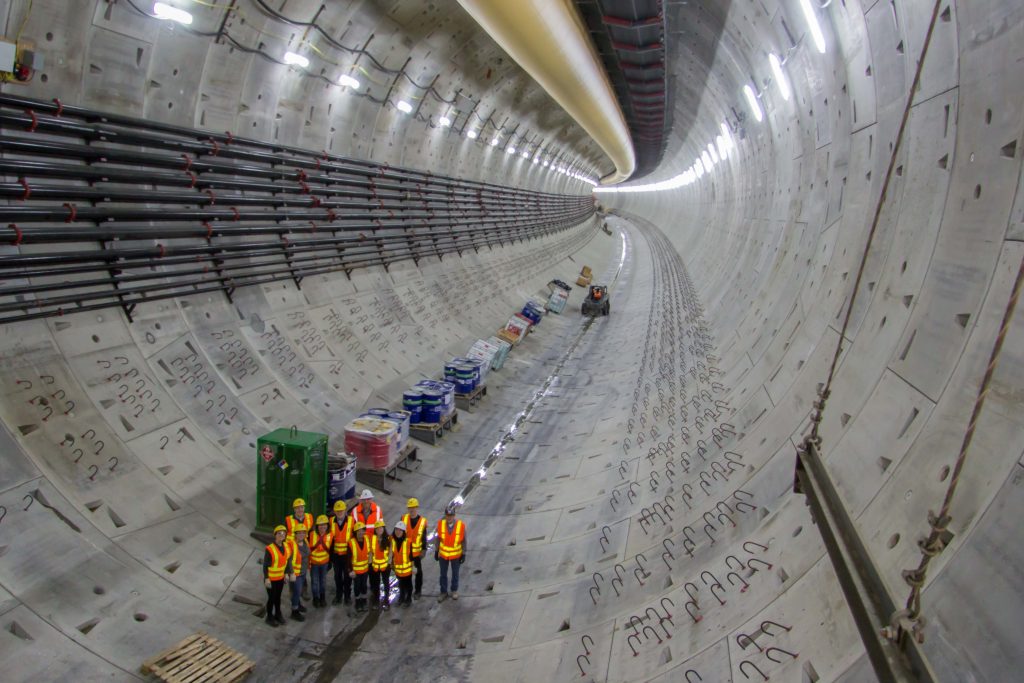

Boosters of the SR-99 tunnel replacing the Alaskan Way Viaduct promised transit improvements to Seattle voters, hoping to win their favor. It turns out, however, the opposite was true. No King County Metro buses use the tunnel, even three years after its opening, and now the tunnel is complicating plans for a second light rail tunnel through Downtown.

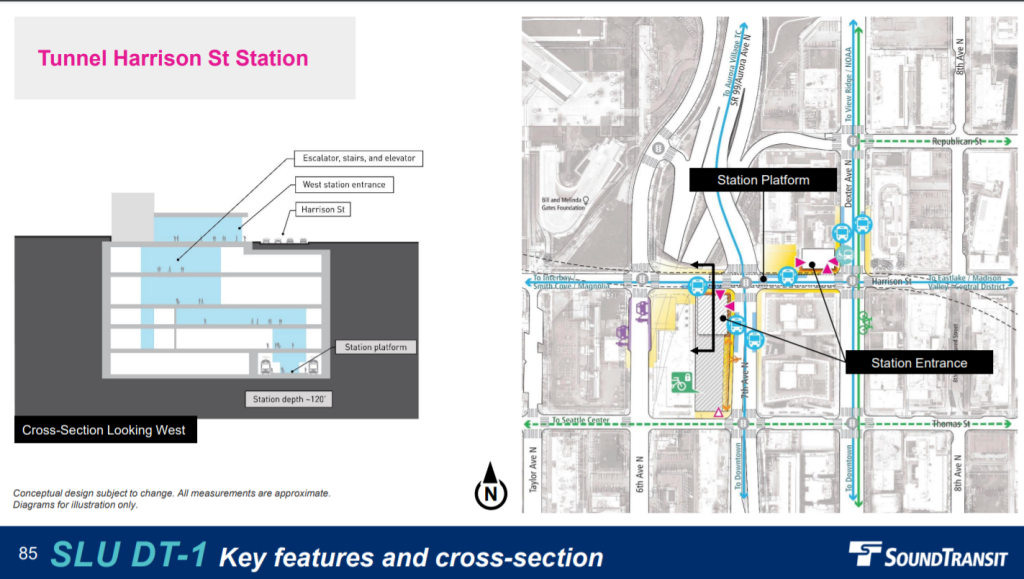

Sound Transit’s preferred alternative would put an underground station at Harrison Street and SR-99. Since this location is right where SR-99 enters a tunnel, it means the light rail station has to be quite deep to clear the car tunnel — 120 feet deep in the agency’s plan. This depth could add nearly five minutes to a transit trip just in navigating the cavernous station and dealing with long escalators or elevators that could have significant queues at a station projected to get 10,500 daily boardings. It will also make the transit station more expensive to build for a transit agency already facing major cost escalation issues.

To add insult to injury, it also puts a station entrance right next to the car pollution venting out of the tunnel, including the four yellow tubes that vent out smoke in case of a fire in the tunnel — hardly a pleasant environment for riders accessing the long station escalators or 11-story deep elevators. Nor is it an ideal location for transit-oriented development. Who wants to live sandwiched next to a busy highway trench and a smokestack?

As co-founder of the People’s Waterfront Coalition, Cary Moon pushed the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to abandon its tunnel plan and support surface transit alternative instead. Unfortunately, WSDOT and other tunnel boosters were relentless and eventually forced through the controversial project despite the fierce opposition from transit advocates and Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn. The tunnel failed a public advisory vote in 2007, but tunnel boosters kept pushing and spinning the project.

False transit promises from highway tunnel boosters

The promise of transit upgrades from highway tunnel boosters, who branded their campaign as “tunnel plus transit,” was intended to outmaneuver and undercut the surface transit alternative that tunnel opponents were pushing. “What does this ‘surface option’ mean for you? More traffic, more delay, buses and freight caught in gridlock,” the pro-tunnel crowd wrote in their 2011 referendum statement. Why back the surface transit alternative when boosters promised Seattle could have a highway tunnel and transit upgrades too?

Unfortunately for riders, the tunnel’s transit plan was built on a hill of lies. Moon and advocates hit the nail on the head when it came to the transit implications, and she points out that the City should have seen this coming.

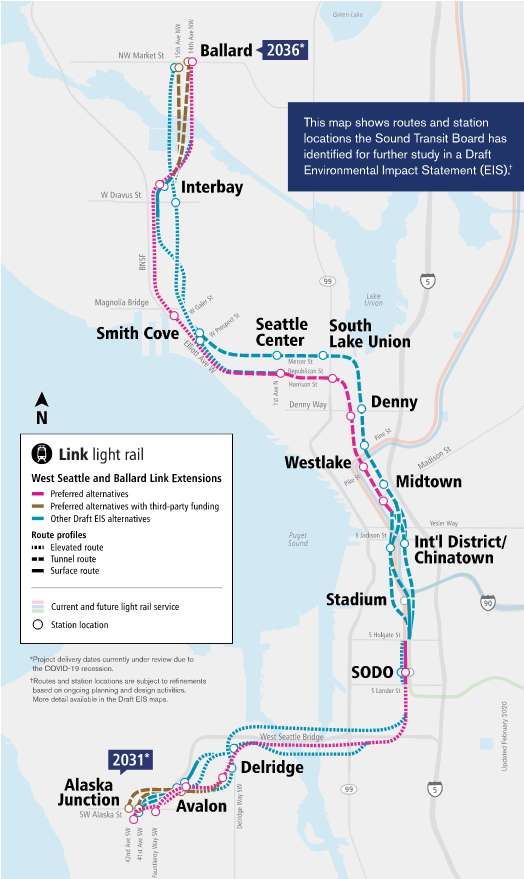

“The City knew back in 2005, when the proposed monorail expansion project was killed, that we would need another approach for rapid grade separated transit to Ballard and West Seattle,” Moon said in a text. “We realized then we’d need another transit tunnel downtown.”

The opportunity cost was enormous.

“What if our region had prioritized Sound Transit as our future then instead of building WSDOT’s four-billion-dollar car tunnel?” Moon asked. “We wasted much time and money and precious underground terrain on perpetuating car culture. We could be choosing a shallower, lower cost, and more accessible second transit tunnel now if we hadn’t.”

The issue of the tunnel has been a wedge in Seattle politics for more than a decade. During his administration from 2009 to 2013, McGinn fought to block the tunnel, but was defeated in his reelection bid by Ed Murray, a major tunnel supporter with robust backing from both the corporate and state Democratic party establishment, who also backed the tunnel. Cary Moon ran against Murray’s successor, Jenny Durkan, and she again took up the cause of transit, climate action, and safe streets for people walking, rolling, and biking over car-focused megaprojects, earning The Urbanist Elections Committee’s endorsement. But Durkan rode a wave of establishment support and bludgeoned her opponent on the issue of homelessness, including hitting her for suggesting the City should build shelter for every homeless person in its borders — a position pretty similar to that held by Durkan’s successor Mayor Bruce Harrell. Harrell, another highway tunnel supporter, now seeks to address a homelessness crisis that worsened under Durkan’s watch despite her campaign pledges to address it.

Governor Jay Inslee called the highway tunnel the “eighth wonder of the world” at its ribbon-cutting ceremony back in 2019 — three years later than promised after the world’s largest tunnel boring machine broke down trying to chew through 1,000 feet of sloppy Seattle soil. The project’s cost overruns were significant even before toll revenue came in far under projections due to WSDOT’s unrealistic and exaggerated traffic modeling — a persistent problem for the agency and the industry. Now, this gift that keeps on giving is driving up Sound Transit 3 costs and worsening future outcomes for riders.

“They told us they were burying the highway through the city, but in fact what they were doing is burying it for part of the city and putting a lot of car infrastructure right into the middle of the city right there in South Lake Union,” McGinn said in an interview. “All of the infrastructure to move cars fast through the neighborhood are inconsistent with what we need to move people in transit in and out of the neighborhood.”

The lack of bus lanes and traffic-clogged bus weave to exit Aurora Avenue is one legacy of that planning mistake, as is the difficulty in moving the bus stop to be next to Sound Transit’s planned light rail station. Like Moon, former Mayor McGinn said the looming issues were obvious.

“We knew that from the start. It’s just that the highway builders really wanted their highway and they didn’t really care that much about the transit users,” McGinn said. “A big highway interchange in the middle of a city is bad urban design. It doesn’t take any particular genius from the planners to see that.”

To McGinn, it all goes back to a flawed philosophy undergirding the deluxe underground highway bypass of Downtown Seattle.

“Why did we build something to skip Seattle instead of to make Seattle better?” McGinn lamented. “The thing about a nice fine-grained street grid is that it supports so many things. It supports buses. It supports walking. It support biking. It supports small local businesses. It can support housing,” McGinn said. “That big [tunnel] portal, what does that support? It supports people who want to miss, in my opinion, the best part of whole damn state and Pacific Northwest. To skip Seattle.”

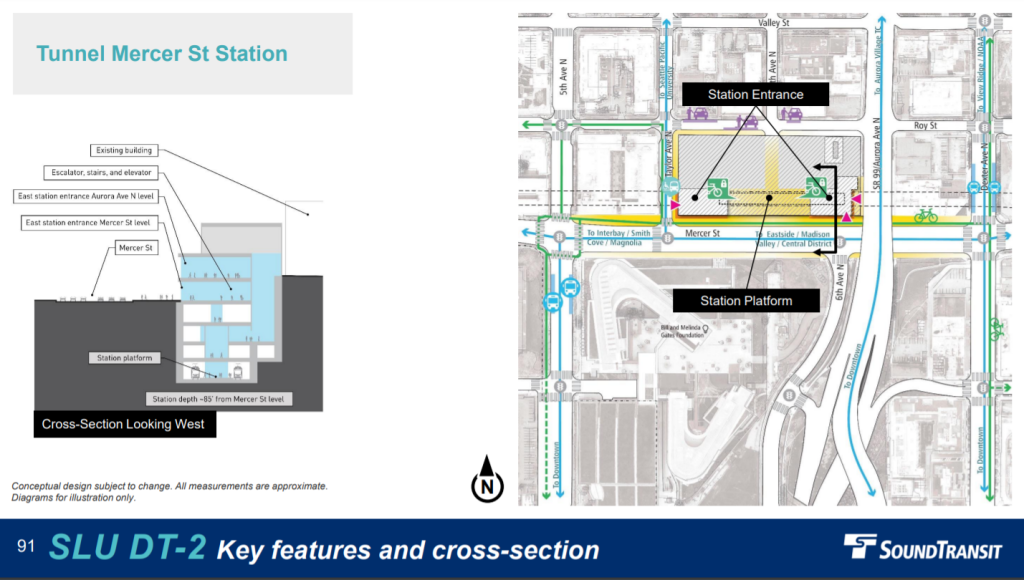

Mercer station alternative also ruined by car tunnel

Unfortunately, the only alternative that Sound Transit is still officially considering was also sabotaged by the highway tunnel project. The other option puts the station at Mercer Street and Aurora Avenue; on the plus side, since it’s north of the tunnel it’s shallower at about 85 feet deep, which should shave a minute or two from the time to surface. However, the bus transfer environment is much worse and the car tunnel project is largely to blame.

With the viaduct replacement project, WSDOT redesigned Aurora Avenue to have a left exit for traffic not entering the car tunnel under Seattle. This traffic included buses weaving over from the right-hand bus lanes on Aurora. Because they’d be in the process of weaving and exiting the off-ramp, there’s no good place for southbound Aurora buses to stop near the Mercer Street station. The weave has also slowed buses down, especially during peak times, which is exacerbated by the fact WSDOT provided no bus lanes on the new off-ramp and no transit priority on the widened 7th Avenue. Needless to say, this was not a transit-oriented project. And there’s not an easy or cheap way to fix it since the left-hand exit is baked into the street design now, barring a complete overhaul.

Salvaging the situation

What’s done is done, but hopefully we learn our lessons from it and adapt the best we can.

The station may have to go at Harrison since getting the bus transfers right is important, but we can mitigate the ill effects of the highway tunnel. WSDOT could help pay the additional cost of excavating the station deeper since it was their project that caused the issue, failing to make good on promises to improve transit. WSDOT could also fund a sound wall to deaden the sound of the highway emanating up to Harrison Street, which would make for a more pleasant station area.

Sound Transit should also do everything possible at other station sites to ensure stations are user-friendly and closer to the surface. South Lake Union Station may need to be 120-feet-deep to clear the SR-99 tunnel, but perhaps the agency will engineer a way for the new Westlake Station to be shallower than the 135 feet planned and find a way to make the 80-foot-deep option at Chinatown-International District work instead of alternatives ranging as deep as 190 feet. The Westlake and Chinatown stations will be essential to get right as the busiest stations and the only ones providing transfers between all three future light rail lines.

The zoning in this part of South Lake Union already allows for 240-foot residential towers, while 160-foot towers are allowed on the Uptown side (west of Aurora). These height limits could be doubled or tripled to allow for a double or tripling of the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements in the area. A doubling could take the mandatory affordability requirement from its current 3.9% of units or a fee of $11.59 per square foot to 8% or $24 per square foot. A tripling could take it to 12% of units or $35 per square foot — a highrise project might pay something like $20 million under such a fee. This would aid in a dense mixed-income neighborhood growing around the station, overcoming the obstacle that the nearby highway presents.

Eventually with more electric vehicles on the road, the tunnel exhaust tubes in the neighborhood would stop belching out as much pollution, although the tire dust from electric cars will still be a significant source of pollution threatening salmon runs. Electric cars would still be noisy at high speeds and remain a drawback on the section of Harrison Street near the station, but a sound wall could mitigate the situation a bit. Transit-oriented development will still arrive near the station, including a social housing tower above the Sound Transit site.

The Gates Foundation is planning an expansion of its campus situated northwest of the station site, which breaks up Taylor Avenue due to a dubious street vacation from decades past. While the Gates Foundation operates a closed campus — it’s literally fenced off from the rest of the city — a pedestrian pathway through the large superblock would improve the walkshed to the station.

Long before the City sold the site to the Gates Foundation for its headquarters, it hosted a trolley barn for the Seattle Electric Company’s extensive streetcar network. Those streetcars were phased out and tracks were ripped out or paved over in the 1940s — although some of the routes were converted to electric trolley buses using the overhead wire for the former trams. Now in the 2020s, we find ourselves trying to shoehorn rapid transit back into a neighborhood that used to be at the nexus of Seattle’s transit network.

The central artery of the neighborhood will likely be Thomas Street, just one block south. Thomas Street is designated a greenway and has been envisioned as a pedestrianized corridor. The City backed off from developing a fully pedestrianized street and closing it to cars, but it did add flexpost protected bike lanes from the Seattle Center to Cascade, providing some street calming. Another plus: Thomas Street isn’t directly adjacent to a highway trench, which confers a basic urban ambiance lacking one block over. Along the street is a mix of recently added or planned mid-rise and older low-rise building that could great transit-oriented redevelopment opportunities. Seattle City Light has a large site that includes a substation. Some of it may have to remain, but perhaps a TOD site could be carved off the campus to add social housing on a city-owned property.

The whole situation would be more favorable without a busy highway next door, but that is the mess we find ourselves in. A whole generation of political leaders assured us Seattle could have a downtown highway tunnel, great transit, and high quality public spaces too. Plans to add a light station in South Lake Union and connect it to pedestrian corridors and Aurora buses will put those assurances to the test.

Correction: An earlier version incorrectly stated the exhaust tubes on Harrison regularly vented car exhaust. In fact, they’re only used in emergency situations like fires. Most of the car pollution vents out the tunnel portals due to “piston action” which still leaves the South Lake Union Station site getting a heavy dose of car pollution.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.