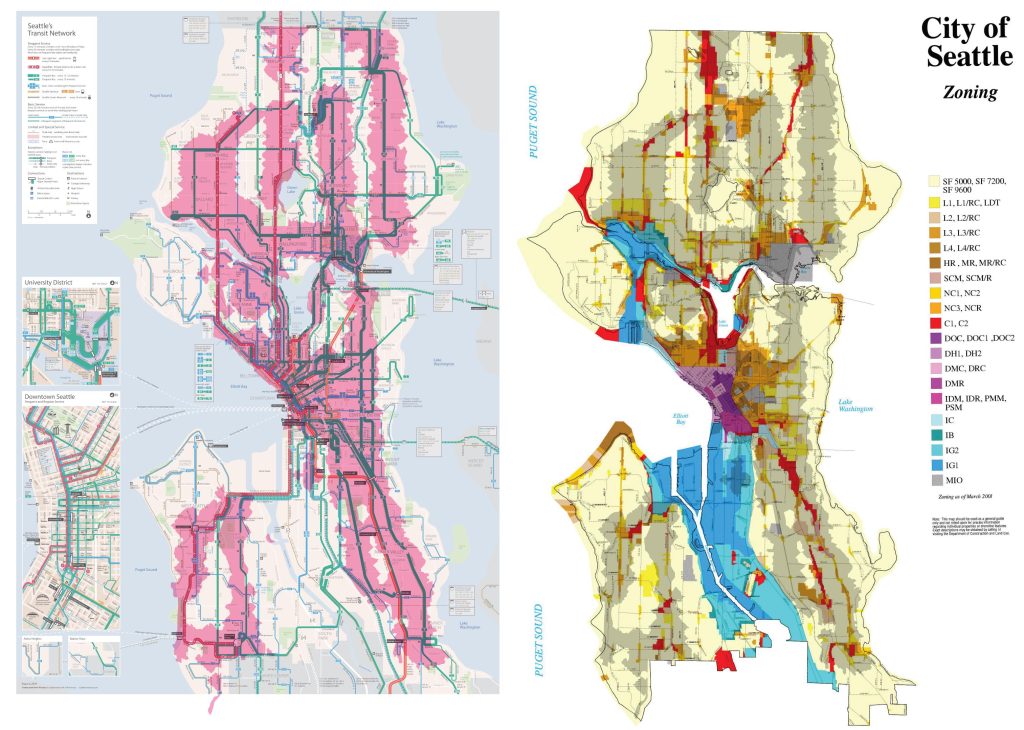

Seattle city planners have long heard the same tired request from neighbors, “Put all housing near transit.” For decades this is exactly what has been done. Seattle created urban villages along arterial streets, some of which are high-crash corridors, on the grounds of enabling “transit access” for residents. As those urban villages areas grew in housing, so did the transit ridership. Over the last 25 years, Seattle’s population has soared, and through this time of population and job growth, single-occupant commuters decreased while transit riders increased.

It’s no surprise that people prefer to read a book or their phone and walk right into their destination rather than sit in aggravating traffic and circle for blocks while looking for high-priced parking. Transit provides easy access from point A to B, and Seattle is getting so close to providing that for nearly all residents. We have arrived at a moment where we are daring to become a real city after all. But doing so will require planning for frequent transit — and subsequently housing — in all areas of the city.

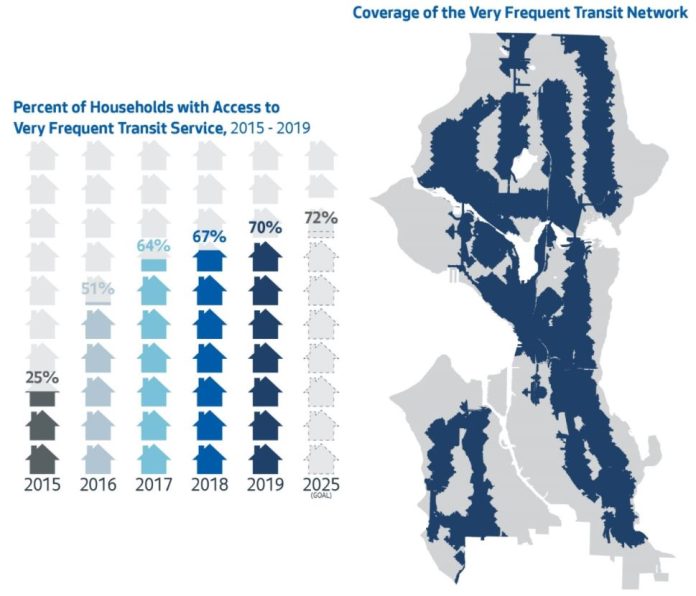

As of 2019, Seattle’s very frequent transit, defined by the City as 10-minute or better all day transit access, reaches 70% of households within a 10-minute walk and housing growth continues to be strongest within these areas.

But there is new impetus to improve transit frequency. HB 1782, SB 5670, and HB 2020, all currently circulating in the halls of Olympia, would bring housing growth to areas served by frequent transit. According to the requirements of HB 1782 (and its companion bill SB 5670), the current bus network in Seattle makes most of the city eligible for the missing middle housing growth, ranging from duplexes to sixplexes, including townhomes and courtyard apartments. This is because the bills only require area to be located within a half-mile of transit service arriving 15-minute or better frequencies during peak hours on weekdays.

HB 2020, which makes it easier to create low and moderate income housing, has some more specific requirements, but also provides greater density bonuses. It operates on the same principle of 15-minute transit frequency as the aforementioned bills, but allows for the construction of affordable housing at nine stories within a quarter-mile of eligible transit, six stories within a half-half mile, and five stories within a mile.

But going beyond that benchmark to make improvements to transit that meet Seattle’s stated goal of 10-minute frequency can help ensure more people are using transit, potential creating a virtuous cycle of housing and transit growth. King County Metro planners should be looking for upgrades to existing routes so none of their service areas are left out of the city’s defined 10-minute transit frequency. With almost the whole city captured in frequent transit walksheds, we can grow homes on quiet streets people like to live on and we won’t have any reason to shove all housing growth to arterials in the guise of “transit access.”

Currently, Seattle has far too much single-family zoning within these walksheds, which means most of the transit investments we have made are going to neighborhoods unable to add housing.

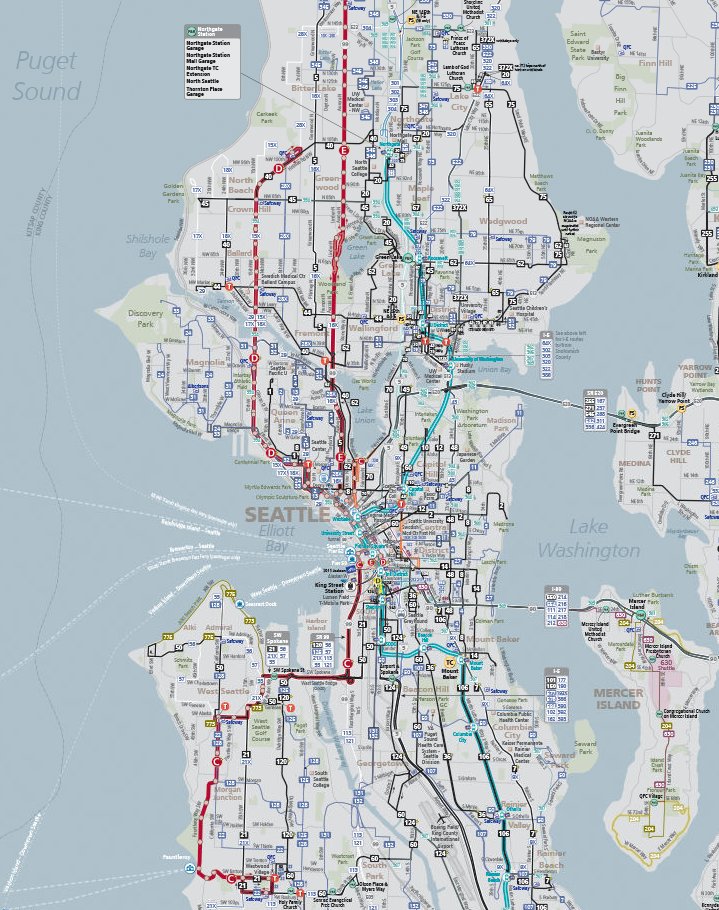

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Seattle has more than 100 bus routes that branch out in every corner of our city. Since most routes meet the requirements of HB 1782 and HB 2020, we only need modest upgrades to be implemented so they can reach the standard of the City’s 10-minute walkshed, further justifying housing growth citywide. This is a simple change that would improve transit access and support growth in neighborhoods like Magnolia, Phinney Ridge, Wedgewood, Queen Anne, and West Seattle. In fact, some of the routes in these neighborhoods already meet the standard or fall just shy. Only a few routes need more attention so their walkshed is captured and the neighborhoods they serve can better contribute to housing growth.

Routes already slated for upgrades to meet the 10-minute standard:

- Route 11 (RapidRide G)

Routes that already met the city’s 10-minute standard in 2019:

- RapidRide C

- RapidRide D

- RapidRide E

- Route 36

- Route 40 (Some upgrades planned)

- Route 44 (Some upgrades planned)

- Route 45

- Route 120 (Also getting upgraded to RapidRide H for good measure)

Routes that need a little boost to reach the 10-minute frequency standard but meet the 15-minute standard:

- Route 2

- Route 3

- Route 5

- Route 8

- Route 10

- Route 12

- Route 14

- Route 21

- Route 48

- Route 49

- Route 50

- Route 60

- Route 62

- Route 65

- Route 67

- Route 70 (RapidRide J will upgrade southern half circa 2024)

- Route 73

- Route 75

- Route 79

- Route 106

- Route 372

Routes that need a big boost or to be redesigned to streamline access and meet either frequency standard:

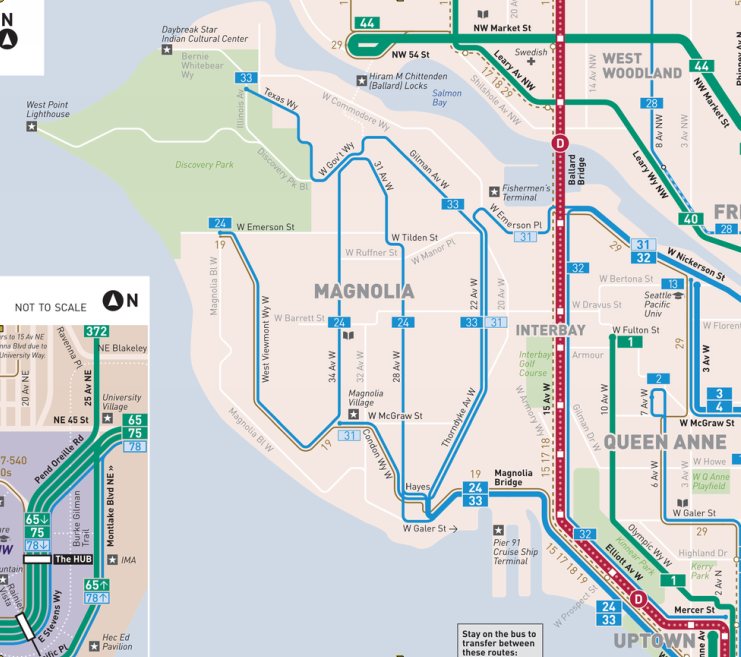

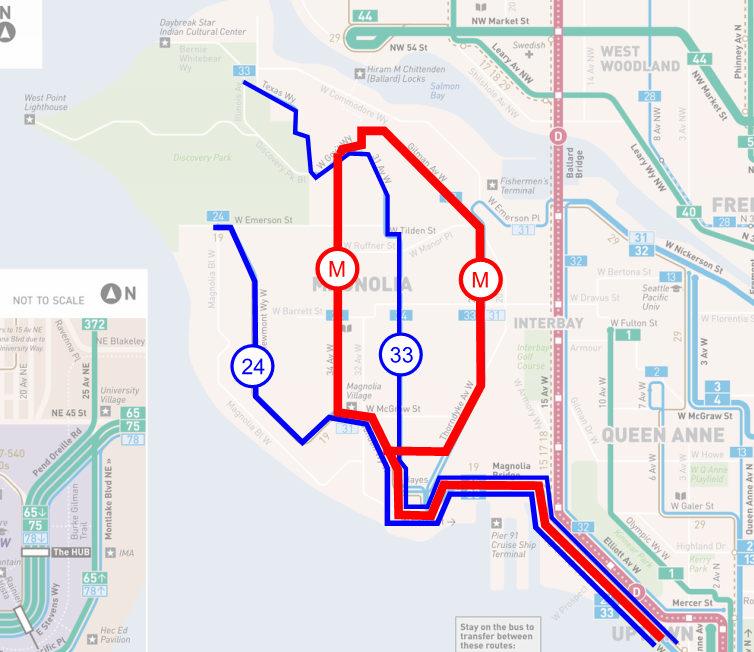

- Route 24

- Route 33

- Route 28

- Route 32

- Route 124

- Route 125

- Route 128

We should also identify areas of the city where these upgrades would make the most significant impact. One area that immediately stands out is Magnolia, which is currently not an urban village, despite being centrally located in the city. A larger planning study could be undertaken to see if a new Magnolia RapidRide route should be added to justify more housing growth. Making Magnolia an urban village and adding denser housing to the neighborhood would help make the expensive replacement of the Magnolia Bridge worthwhile by ensuring the bridge would carry large numbers of transit riders rather than a small amount of residents who want to shave a few minutes off their drive. A new RapidRide route in Magnolia would allow for lines 24 and 33 to streamline, straighten out, and access more of the neighborhood directly, without having to zig and zag through the low-density suburban planning. It would capture the core of the neighborhood — which is the only area currently allowed for housing growth — and justify future denser housing investments.

Housing needs to keep up with jobs

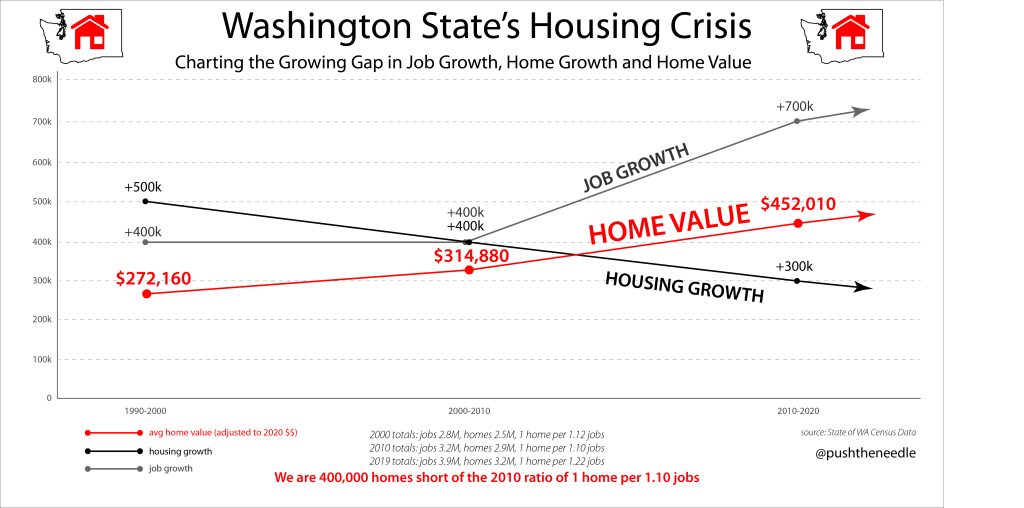

Seattle must do its part to keep up with the increased job growth. Job growth attracts people and drives up housing costs if not accompanied by an increase in housing supply. As it currently stands, the city is 45,000 homes short of matching the jobs to homes ratio defined in 2010. Zooming out, the state is in an even more dire situation. Washington State is 400,000 homes short of matching the ratio from ten years ago, so it is no wonder the state legislature is stepping in.

Let’s include the whole city

The bottom line is that no areas of Seattle should be off limits from housing growth. However, simply increasing zoning capacity without upgrading services like transit will only bring on community resistance to change. With the current proposed legislation, the state is giving Seattle the opportunity to allow housing growth in every neighborhood instead of shoving density on arterial streets while leaving single family neighborhoods untouched. Seattle should embrace this opportunity — and we should make sure we bring housing and transit to all areas of the city.

Ryan DiRaimo

Ryan DiRaimo is a resident of the Aurora Licton-Springs Urban Village and Northwest Design Review Board member. He works in architecture and seeks to leave a positive urban impact on Seattle and the surrounding metro. He advocates for more housing, safer streets, and mass transit infrastructure and hopes to see a city someday that is less reliant on the car.