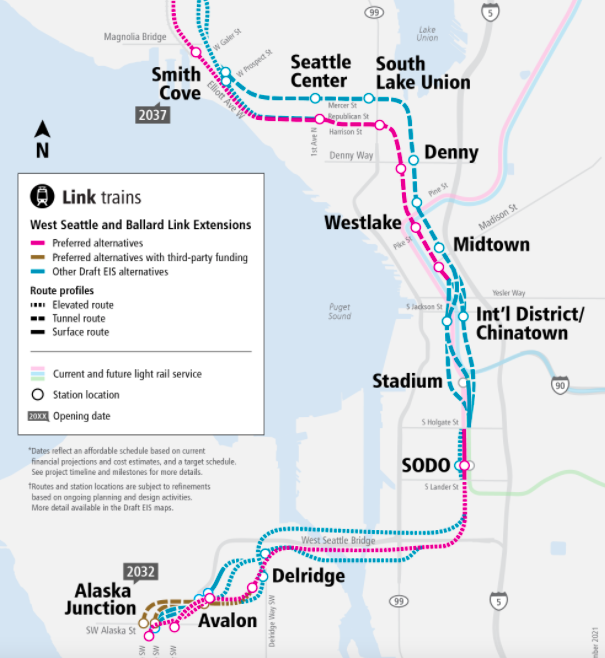

Sound Transit is planning a pair of new transit lines through Seattle to build on the rapidly expanding Link light rail system. The West Seattle and Ballard Link Extensions (WSBLE) will serve 13 new stations through some of the city’s densest neighborhoods, requiring a second downtown tunnel and new tracks south of downtown paralleling the existing Link 1 Line. This new infrastructure could instead support a new rail system using driverless train technology, the global standard for high-capacity rapid transit lines (such technology is often referred to as “driverless metro” or “automated metro”). Sound Transit is planning to build WSBLE using costlier operator-driven light rail technology that cannot operate as frequently as a driverless metro system.

Automated metro systems have a number of benefits over traditional light rail. Because the automated trains don’t need a driver, they can be operated at higher frequencies than traditional light rail or subway systems, and at a fraction of the cost. This also means that an automated metro line can have much higher passenger capacity than a light rail line, even though the latter uses larger trains. Implementing four-car automated metro trains instead of four-car light rail trains would mean station platforms could be shorter — less than half the length of the platforms Sound Transit’s Link system uses today. As stations contribute a large portion of the expense of constructing new transit lines, shortening the length of the platforms has the potential to significantly reduce capital construction costs.

For comparison, here’s a statistical breakdown of Vancouver, Canada’s next SkyTrain automated metro Broadway Extension and the WSBLE:

| SkyTrain Broadway Extension | West Seattle + Ballard Link | |

| Train Technology | Driverless Automated Metro | Traditional Light Rail |

| Project Cost (USD) | $2.2 billion | $12.1 billion |

| Extension Length | 3.5 miles | 11.8 miles |

| # of Stations | 5 stations | 13 stations |

| Cost Per Mile | $634 million per mile | $1.025 billion per mile |

Of course, these cost estimates don’t tell the whole story, but they hint at why light rail is not the ideal mode for WSBLE. While transit infrastructure projects in the United States tend to cost several times the global average, Link’s per-mile cost for WSBLE has ballooned out of control to the point where it is higher than the US average for subway tunneling, despite being largely above ground. Vancouver’s automated SkyTrain has also seen construction costs increase over the years, but its system expansions are still estimated to be significantly cheaper than Seattle’s.

The operational argument

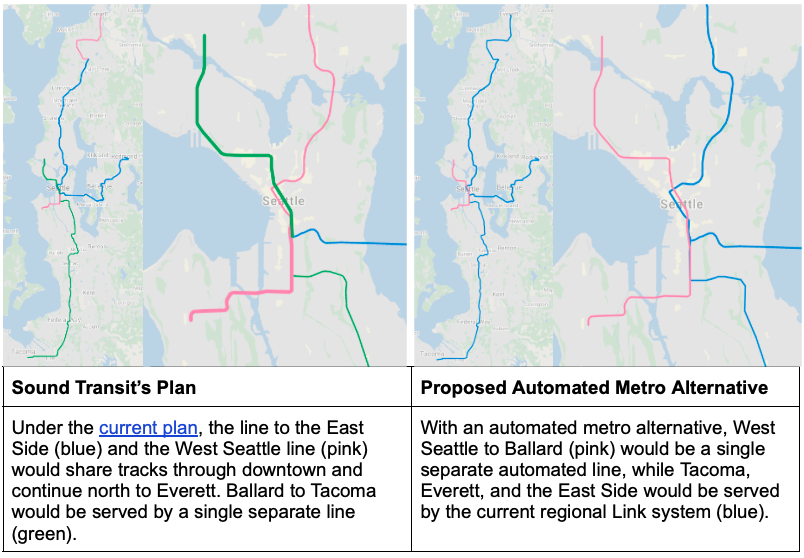

Sound Transit’s plans for WSBLE call for a line between Alaska Junction in West Seattle and Everett, and another between Ballard and Tacoma. The West Seattle line would have its frequency limited to a maximum of one train roughly every four to six minutes due to using the same tracks as the East Link line (also projected to be very busy) through downtown. The line to Ballard would have its frequencies similarly limited by the existing in-street section through the Rainier Valley, which can only handle one train every six minutes. Such low capacity could prove critically inadequate in the future for lines serving some of the busiest transit corridors in the region.

According to Sound Transit, the reason for this line configuration is that operating a single light rail line that is more than 60 miles long between Everett and Tacoma would be challenging. They also point to splitting passenger loads between a pair of light rail alignments so that riders on the major northern and southern arteries of the Link system do not all end up in the same packed trains through downtown.

While Sound Transit’s plan alleviates the operational and capacity constraints of the current regional Link system, doing so at the expense of the new urban lines’ frequencies will immediately hamstring WSBLE’s usefulness.

In addressing the operational challenges Sound Transit brings up, individual light rail trains do not need to operate all the way from Everett to Tacoma. Track switches and spare pocket tracks that already exist at certain stations would allow trains to turn around and only serve the busier core parts of the system. For example, trains from Tacoma could turn around at the Northgate Transit Center and Everett trains could do the same at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport or head to the Eastside rather than Tacoma. Long-term investments in train throughput, such as signaling improvements, and higher train frequencies in core sections would be a more proactive way to distribute rider loads and prepare for the Link system’s long term capacity challenges.

The proposal

Combining WSBLE into a single automated metro line would enable significantly higher frequencies to West Seattle and Ballard. Automated metros in cities around the world are inexpensively operated at headways (the time between trains) of every three minutes or less, meaning passengers never have a long wait before their train arrives. Such high frequencies reduce crowding during busy times of day and enable a kind of turn-up-and-go flexibility that makes automated metro service much more appealing to potential riders. That flexibility will be crucial if we expect people living near WSBLE to depend on the line for their day-to-day needs.

In the future, automated trains could theoretically operate across the existing Link system as well, but this would require reconstructing or diverting trains around the capacity-constrained portions of the system that run in the middle of streets through Bel-Red and the Rainier Valley. While doing so might make sense as a long-term investment, automating WSBLE is the lowest-hanging fruit because the expansion is planned to be fully grade separated.

The realities of automated metro trains in Seattle

Automated metro trains on WSBLE could be feasibly implemented using existing technology, which dozens of systems across the world have already proven to be effective. Using driverless train technology, cities like Milan, Italy, run four car trains that are 167 feet long and, capable of running once every minute, have a maximum capacity of more than 24,000 passengers per direction per hour (ppdph). Link’s current light rail technology requires 400-foot long trains, resulting in longer stations. Even with optimal frequencies in core sections, the light rail system’s maximum passenger capacity is just 16,000 ppdph.

While automated metro systems provide a number of operational benefits, implementing such a system in Seattle would not be without a few drawbacks. The most obvious is that, because the automated metro trains would be incompatible with existing light rail trains, a new operations and maintenance facility (OMF) would have to be built. This wouldn’t be cheap. Recent estimates for Link’s future OMF South in Federal Way put the cost as high as a whopping $1.4 billion to store a hundred or so additional trains. A new OMF for the WSBLE would need to be built somewhere near the line’s planned route, which passes by plenty of parking lots, rail yards, and industrial warehouses through SODO and Interbay that could fit such a facility. However, a new automated metro maintenance facility could potentially eliminate the need for the planned OMF North, negating or significantly reducing the added costs. Other drawbacks would be the upfront cost of the automation system and a lack of fleet commonality, requiring two distinct maintenance crews.

These added expenditures would be dramatically outweighed by the financial benefits of being able to construct smaller stations, combined with the immediate and long term operating cost savings of an automated system. The lack of drivers means increasing serving levels has a negligible impact on operating costs. That is a stark contrast with the current plans, in which every train we run would add labor costs that we could be spending to increase service on other parts of the system. The precision and efficiency of computer-driven automated trains also allows them to use up to 30% less energy than driver-operated vehicles. Driver error would no longer be a factor, platform screen doors at stations could keep people off of the tracks, and higher frequencies would drive ridership. Overall, automated metro could prove extremely beneficial to the Seattle area, if only we are willing to look outside our comfort zone and consider the best technology for the region’s long-term needs.

Sound Transit deserves tremendous credit for the success of its light rail system and the steady momentum of expansions. However, that momentum shouldn’t close us off to the world outside of what we already know. Link in its current form can only take us so far; the boom in automated systems suggests driver-operated light rail is becoming an outdated technology. If we were willing to open our eyes to the successes of cities across the globe, it would become apparent that we need to be building WSBLE as an automated metro line.

Emmett Broustis (Guest Contributor)

Emmett Broustis is a high schooler in North Seattle. He likes to walk or take the bus whenever he can, and is passionate about the ways public transportation can change the urban fabric of cities. Emmett has pragmatic views on urbanism and transit, and is generally excited for the much-needed changes Seattle is embarking on.