Who should generally have the burden of proving liability in a crash between someone walking or rolling and someone driving a car: the person using the several thousand pound vehicle or the person on the receiving end of the kinetic energy of that vehicle? This is an issue that the state legislature may have to grapple with in the coming weeks as it considers a proposed bill. The context is a pedestrian-related safety crisis in Washington, as the number of pedestrians seriously injured or killed in traffic collisions continues to increase every year.

According to Washington State law, if a street has a sidewalk alongside it, any pedestrian using the street is required by law to use it. “Where sidewalks are provided it is unlawful for any pedestrian to walk or otherwise move along and upon an adjacent roadway,” RCW 46.61.250 states. “Where sidewalks are provided but wheelchair access is not available, persons with disabilities who require such access may walk or otherwise move along and upon an adjacent roadway until they reach an access point in the sidewalk.” If a pedestrian encounters a sidewalk that is in such poor condition that it isn’t usable, a common occurrance in cities like Seattle, to comply with the law a pedestrian would actually need to cross to the other side of the street if there is a sidewalk on that side.

If a street is missing a sidewalk, the law requires pedestrians to use a shoulder, and if a shoulder isn’t available, pedestrians are required to move out of the way of oncoming traffic if they are able. “Where sidewalks are not provided, any pedestrian walking or otherwise moving along and upon a highway…shall, when practicable, walk or move only on the left side of the roadway or its shoulder facing traffic which may approach from the opposite direction and upon meeting an oncoming vehicle shall move clear of the roadway,” the law continues. The law dictates where pedestrians should be walking on a street without a sidewalk and forces them to cede the right of way to an approaching vehicle if it is “practicable,” which is clearly subjective.

In contrast, state law governing the behavior of a driver encountering a pedestrian walking along a roadway for whatever reason is that “every driver of a vehicle shall exercise due care to avoid colliding with any pedestrian upon any roadway” — in other words the statute assumes the driver has a right to be there that is not similarly afforded to the person walking, an imbalance that can impact the legal standing of any pedestrian who finds themselves in court as a result of a collision.

In late 2020, the Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Council, the secretive offshoot of the Traffic Safety Commission whose mission is to address safety issues that impact people who walk and roll, released a report recommending a way that this statute be amended to address some of the problematic elements — by applying the same “due care” standard that applies to drivers to pedestrians.

SB 5687, introduced by Senators Claire Wilson and Marko Liias, would do just that. “When walking or otherwise moving along and upon an adjacent roadway, a pedestrian shall exercise due care to avoid colliding with any vehicle upon the roadway,” is how the added language is stated in the bill. Tomorrow, the bill gets a public hearing in the senate transportation committee following a work session on the current state of traffic safety in Washington. (You can sign up to testify in person or in writing here.)

The 2020 report notes that dictating by law which side of a street a pedestrian should be walking along when there isn’t a sidewalk present is problematic. “People on foot should legally be allowed to determine which side of the road is safest for them. Because for drivers, their ability to see pedestrians is the same whether they are looking at them from the back or front,” it said.

Shelly Baldwin, Director of the Washington Traffic Safety Commission, explained the impetus behind asking for the language to be added. “The standard for liability for drivers is due care,” she said, “but the pedestrian cannot legally be in the roadway. By adding the due care clause [for pedestrians] the Active Transportation Safety Council is trying to allow that legal defense.”

But Bob Anderton, the founding attorney at Washington Bike Law, doesn’t see the added language as being clearly beneficial to a pedestrian trying to defend their presence in the roadway. Anderton notes that Washington’s pattern jury instructions, summaries of current laws provided by a presiding judge to a jury, already notes that a pedestrian has a standard of due care. “It is the duty of every person using a public street or highway [whether a pedestrian or a driver of a vehicle] to exercise ordinary care to avoid placing [himself or herself or] others in danger and to exercise ordinary care to avoid a collision,” WPI 70.01 states.

“I worry this adds complexity… if the goal is to make it safer for pedestrians, we should clarify the law and not add stuff nobody understands,” Anderton told me. He would modify the existing language, not simply add additional sentences onto it, to clarify what it means for a pedestrian to be exercising due care when using a roadway with or without a sidewalk. In the meantime, Anderton is concerned this change in law could be worse than the status quo.

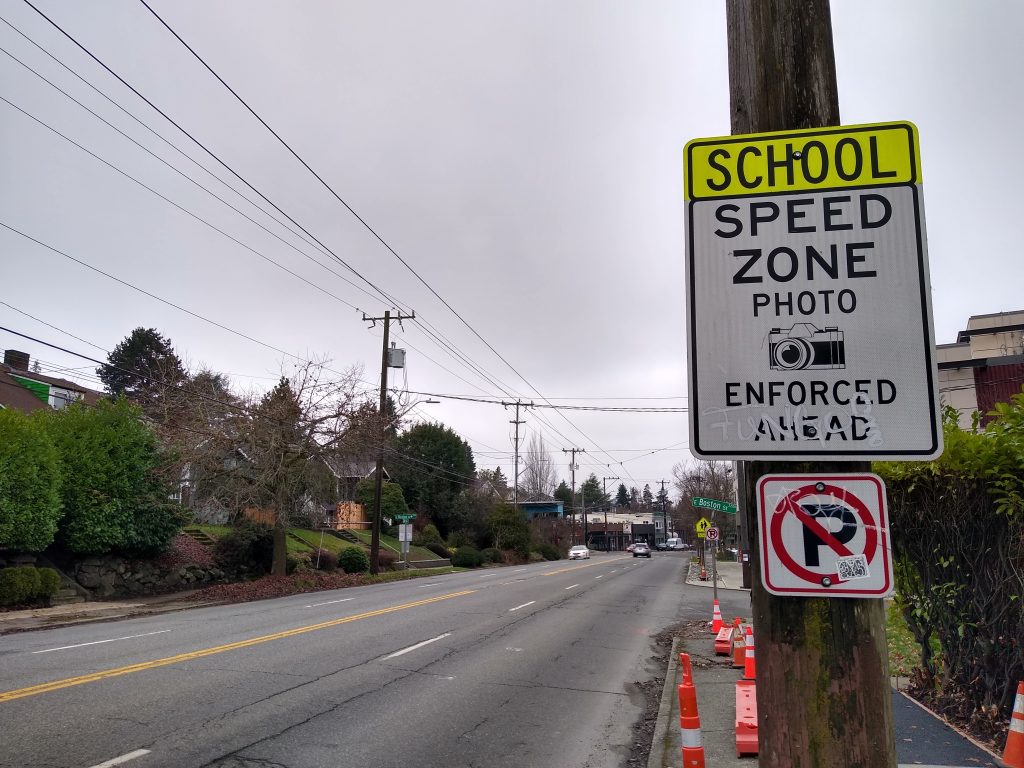

The change to add a due care standard for pedestrians isn’t the only modification to current traffic laws that would be made by SB 5687 — there are several other modifications around traffic safety included in the bill. One additional big change is that it would allow municipalities across the state to expand where they place automatic cameras to ticket speeding drivers around schools. Currently cameras can only be placed close to a crosswalk immediately adjacent to the school — this bill would allow speed cameras to be placed in an entire school’s designated safe walking and biking route, which generally extends a mile or so away from the school.

There are several other bills dealing with automatic speed cameras that have been introduced so far this session. In the House, HB 1915 would simply allow speed cameras to be placed near parks and hospitals. HB 1969 is more complicated, allowing speed cameras to be placed at locations with frequent collisions, as well as near parks and community centers, and locations with a history of street racing. It would restrict the number of new cameras allowed in a city under the law based on its population (1 per 10,000 residents), a restriction that doesn’t currently exist. And it would siphon away 50% of the revenue generated locally and give it to the state, in the same way that Seattle’s current block-the-box camera pilot does. That bill also includes a section requiring cities to evaluate “livability, accessibility, economics, education, and environmental health” when considering where to place cameras.

Director Baldwin noted that a vehicle’s speed is the single biggest determinant of whether a pedestrian involved in a traffic collision survives: “Camera enforcement is a really good way to keep speeds down,” she told me. “I think it’s great to see these [speed camera] bills.”

Back to SB 5687, there are a few more tweaks it would make to state law. It would fully codify the rights of cities and towns to set up open streets, like the Stay Healthy and School Streets that have been deployed by Seattle since the early days of the pandemic. Previously state law wasn’t completely clear on whether cities could permit pedestrians to walk in the roadway via signage: Seattle’s open streets have tried to adhere to the law by utilizing “street closed” signage even when the streets were intended to be open to vehicles for local access. The sections of the law regulating when pedestrians can and cannot use the roadway “do not apply when the roadway is duly closed to vehicular traffic by placement of official traffic control devices for the sole purposes of pedestrian and bicyclist use of the roadway.”

Another tweak would codify the ability of jurisdictions around the state to set a 20 mph speed limit on all non-arterial streets; a previous change to state law only allowed that in “residence or business districts.” Those are a lot of small but impactful changes to how state traffic law handles the current pedestrian safety crisis as Washington comes out of a year where traffic fatalities statewide were at their highest levels since 2006. Grappling with the introduction of a new “due care” standard for pedestrians may prove more complicated for lawmakers to handle than the other changes that have been proposed.

SB 5687 will get a hearing tomorrow at 4pm in the senate transportation committee; you can submit comments online or sign in “pro” and “con” without testifying in person here.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.