As a coordinator for an outdoor preschool, Eya Lazaro helps families of color find greenspaces across the Puget Sound for their young children to safely learn, explore, and play in nature. But in South King County, finding parks that families live near or can access is challenging.

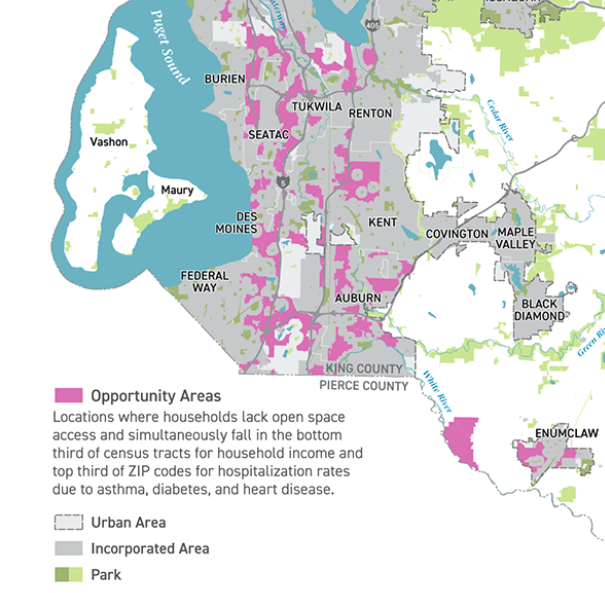

According to an open space disparities map, at least eight cities south of the Seattle limits lack open space in communities that are low-income and who experience high hospitalization rates for asthma, diabetes, and heart disease. The most racially and ethnically diverse populations of South King County are concentrated in this same area.

“One of the things in Tiny Trees that we are mindful about when we’re opening up new classrooms is the communities we are in, and how we can be more accessible to them. We had a classroom in Federal Way that we had to close, because it wasn’t very accessible or known to families,” Lazaro said. “Communities of color are three times more likely to not have access to greenspaces. And that’s because of systemic racism.”

To show just how wide the gap is for her preschool’s families, Lazaro recorded a video of herself taking the bus and walking from central Seattle to the beach at Seahurst Park – one of her classrooms in Burien. It took her three hours round-trip.

Federal funding through the Outdoors for All Act (OFA) would address both greenspace deficiencies and park access inequities.

OFA would expand the Outdoor Recreation Legacy Partnership (ORLP) and deliver funding to build new parks and amend existing ones in communities, many of which are low income and have a greater proportion of Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Cities of 50,000 are currently eligible to apply to the ORLP program; OFA would expand access to the program to communities of 30,000 or more. That exceeds the population of many South King County cities including Burien, where about 21% of people don’t have a park within a 10-minute walk of their home, according to The Trust for Public Land. The Seattle Parks Foundation, REI Co-Op, and Wilderness Society – who promoted Lazaro’s video – endorsed the legislation. Unfortunately, the OFA is in a holding pattern as Congress negotiates the next steps with the stalled Build Back Better package. However, the OFA can move beyond Build Back Better, because it is standalone legislation and can be attached to various other policy frameworks that start to emerge this year.

If OFA passes, cities would first need to apply for ORLP funding through Washington state, who would vet and send applications to the National Park Service for selection. For any recreational federal funding granted to Washington state, a bulk of it goes through the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO) for management and delegation to local governments and organizations, who then apply for it through state grants. Not all communities are able to participate in the highly competitive and long process, or they cannot afford to match funds.

“The communities have to put in funding as well, and initially that was 50%. For a city like Seattle, they have a good tax base, and they can come up with a 50% match on projects relatively easily, whereas a lot of smaller communities, you know, they want to do a $500,000 park, they don’t have that given $250,000, and that’s especially the case for several communities in South King County,” said Christine Mahler, the executive director of the Washington Wildlife & Recreation Coalition – who advocates for park funding for cities like those in South King County. “It’s also a matter of making sure those greenspaces are appropriate for the community and the environment.”

Match reduction has been decreasing since 2016 for some communities. The 2021 Washington legislative session dedicated $375,000 in operating funds to RCO for a comprehensive equity review that will identify changes to policy, operations, and practices to better serve historically underinvested communities. RCO will complete the full equity review in June and give its funding board a report in mid-January.

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.