The winter holidays gifted Seattle thousands of cancelled flights, likely affecting over 100,000 travellers. Today, weeks later, people are feeling the impacts as airlines try to work through the backlog. I can relate. I’ve had my fair share of terrible flying experiences, including a trip just last November. These experiences are so common that virtually everyone is numb to complaints. I personally hope there’s enough exasperation with airlines that people might consider real solutions, like high-speed rail.

My last terrible flying experience was a trip from Columbus to St. Louis. There are no direct flights between these to major cities, so you can drive 6.5 hours, bus 7.5 hours, or spend 4.5 hours flying through Chicago.

Since we were just spending three days in St. Louis, we chose to fly. Our flight departed 40 minutes late and then spent 45 minutes on the tarmac in Chicago. We ran to our connection and saw the airplane still attached to the jet bridge, but alas, they didn’t let us board. The gate was closed. A customer service agent told us the problem was coded as “weather” — so no compensation — and the earliest flight we could get on would be 1pm the following day. Our three day trip turned into a two day trip.

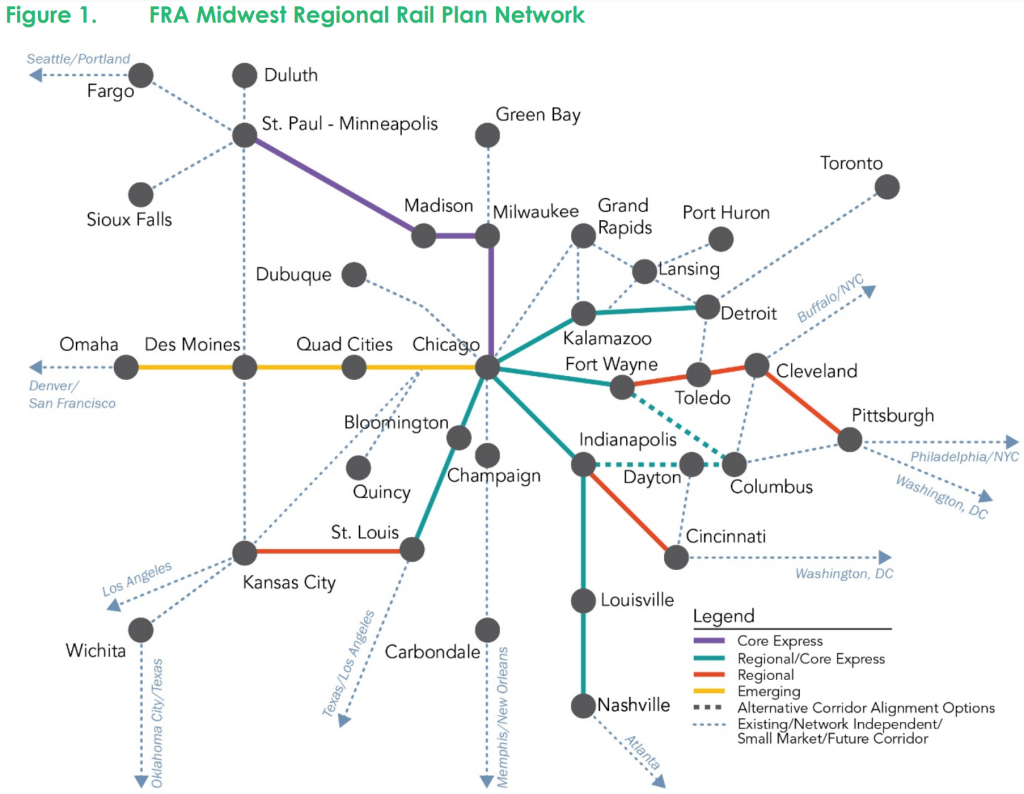

A high-speed rail network could dramatically change this situation. And recently, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) worked with states and local organizations to lay out what that Midwest network might look like.

Unfortunately, the proposed alignments still don’t have a direct route from any Ohio cities to St. Louis. Instead, the proposal recommends a hub-and-spoke system where nearly everything runs through Chicago. Much of it is not really a high-speed rail network, more like “higher” speed. Only on “Core Express” corridors will train speeds exceed 125 mph, while the “Regional” sections will be in the 90 mph to 125 mph range under the FRA plan. An incremental upgrade on the Chicago to St. Louis segment is already under development and last month saw speeds on some segments increase to 90 mph and will see some 110 mph sections once it’s done. When that corridor will achieve its planned “Core Express” status, with speeds above 125 mph, is not yet clear. As of now, the total travel time is 5.5 hours to cover 284 miles.

It’s an improvement but hard to get excited about when compared to a truly high-speed train, which could cover that distance in less than two hours with stops. In a world with high-speed rail, we would’ve skipped the flight entirely, choosing the climate friendly option. And any route connecting Columbus to St. Louis — even a route through Chicago — would likely be faster than flying.

Any list of potential benefits could be long. Trains could be automated and run with minimal staff, allowing around the clock service at a low cost. Economic benefits would flow to mid-size cities that have seen their airport service gutted following the deregulation of airlines under the Carter and Reagan administrations. Downtowns would benefit, improving urban life.

The list could go on and on but one under-discussed, big benefit is that it would create real pressure on airlines to provide better service. It would reduce their lobbying power, making regulation more likely. It would give people a choice between a tiny coach seat and a comfortable train ride. A choice between tiny, salty snacks with half a can of pop and a proper dining car.

Most recently in Seattle, Cascadia Rail might have provided an alternative for the people stranded at Sea-Tac Airport since there are about 21 direct flights to Portland, 14 to Vancouver and 17 to Spokane every day. Cascadia Rail may have reduced the pressure on the airport and many people would have arrived at their destinations a whole lot sooner.

And yes, complaining about airlines may seem privileged but it’s worth noting there can be more serious impacts. When I get stranded, I can afford a hotel but some people can’t and the airlines aren’t paying for that. When we were waiting to get our flight rescheduled, the person next to us was trying to get a new flight to Buffalo, New York. They were a photographer with a wedding gig the next day. Unfortunately, the earliest flight American Airlines would put them on arrived after the wedding was over. Tough luck, I guess.

Update: This article has been updated to clarify what planned speeds are under the Federal Railroad Administration’s Midwest Regional Plan.

Owen Pickford

Owen is a solutions engineer for a software company. He has an amateur interest in urban policy, focusing on housing. His primary mode is a bicycle but isn't ashamed of riding down the hill and taking the bus back up. Feel free to tweet at him: @pickovven.