Washington could follow in the example of Oregon and California by chipping away at the predominance of single-family zoning across the state with new proposed legislation, House Bill 1782 and companion Senate Bill 5670.

“It’s time for Washington to lift bans that prevent the construction of modest home choices like duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and cottages,” Representative Jessica Bateman (D-22nd District), one of the bill’s sponsors, said in an email. “We are experiencing a housing crisis in every corner of the state with families spending up to half their income on rent.”

That crisis is racialized and linked to the homelessness crisis.

“This disproportionately hurts communities of color, who have been historically harmed by redlining and are more likely to be renters,” Bateman added. “By allowing these modest homes choices, in high opportunity and amenity rich areas we can unlock opportunity for Washington families and ensure everyone has a place to call home.”

In addition to Representative Bateman, the bill was sponsored by Nicole Macri (D-43rd District), Liz Berry (D-36th District), Joe Fitzgibbon (D-34th District), and Cindy Ryu (D-32nd District), and a companion piece has been filed in the State Senate by Senator Mona Das (D-47th District) and Patty Kuderer (D-48th District). The bill was requested by Governor Jay Inslee and included within his proposed homelessness plan.

The key to increasing density in this bill is missing middle housing, for example small multifamily developments like duplexes, townhomes, rowhouses, and courtyard apartments.

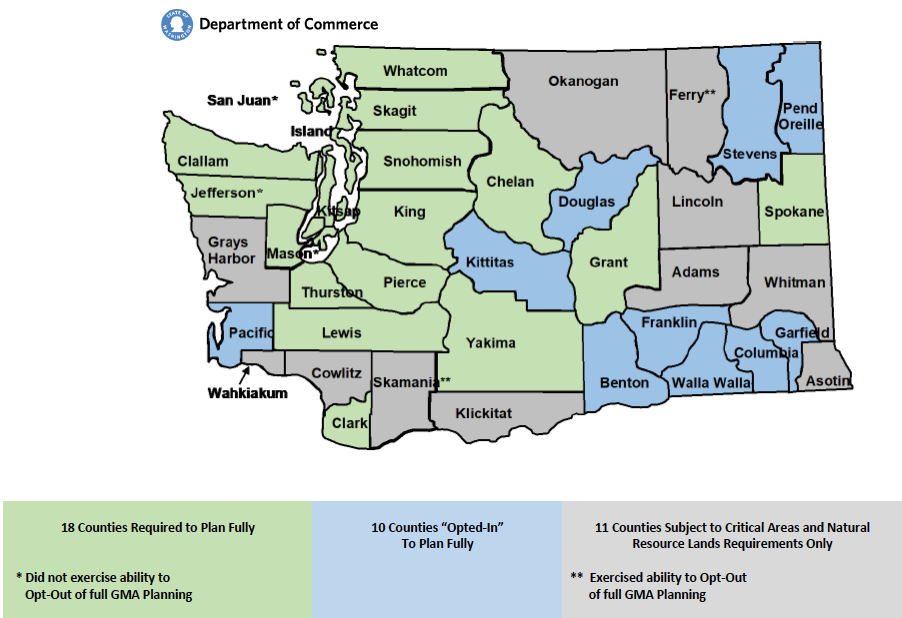

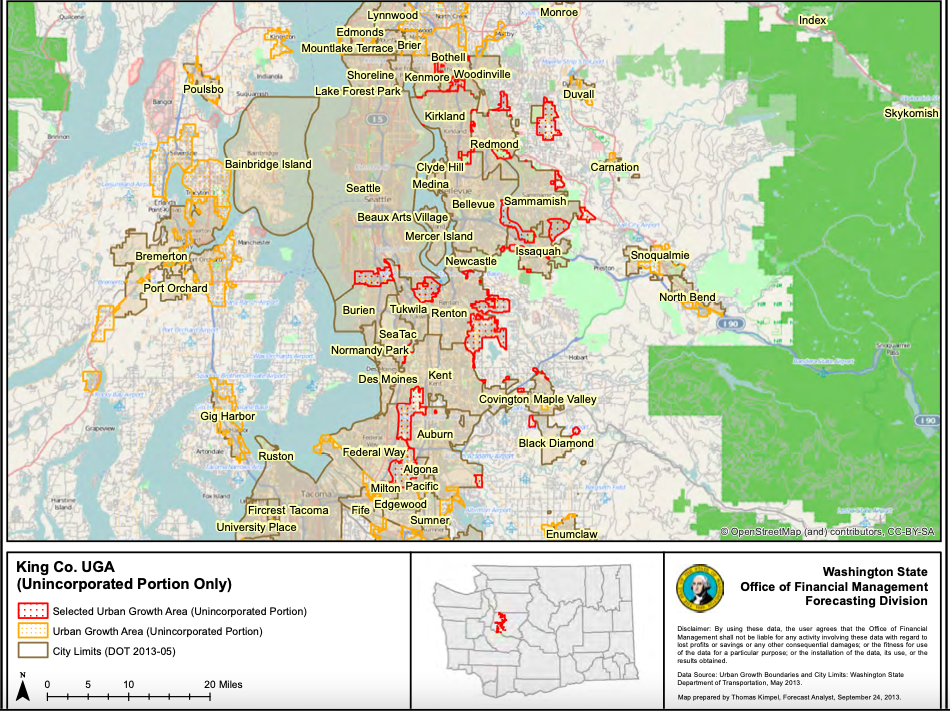

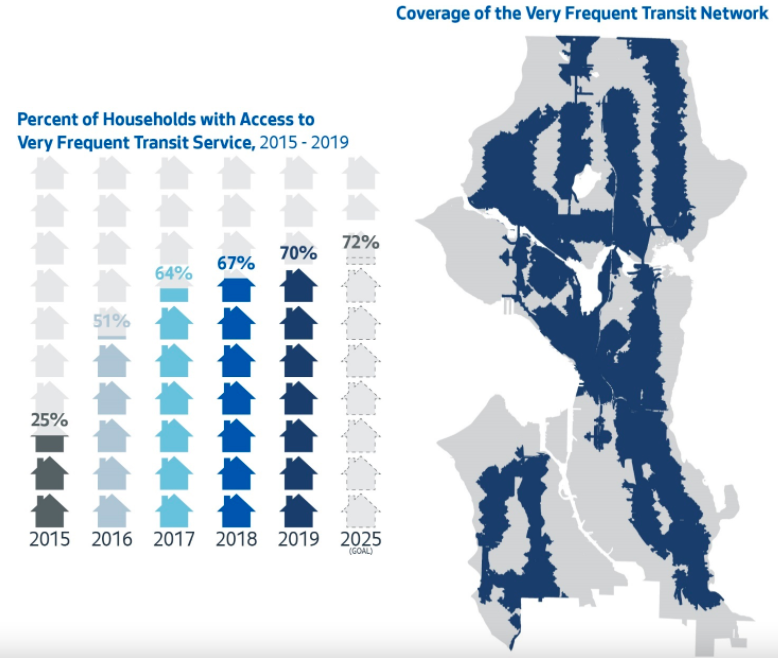

If it were to pass as written, the law would require cities with a population of at least 20,000 and planning under the state’s Growth Management Act (GMA) to allow for duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes to be constructed on all lots zoned for detached single-family homes. In areas within a half-mile of a major transit stop, which is defined as a stop for high capacity transit (e.g., light rail), commuter rail, fixed rail (e.g., monorail and streetcar), bus rapid transit, state ferry terminals, or any bus stop providing service at least every 15 minutes during certain weekday peak hours, these cities would also need to allow for all missing middle housing types, including sixplexes and townhouses.

In Seattle, most residential areas have transit service that meets that benchmark, meaning sixplexes and townhouses could be built in much of the city under the proposed law. In 2019, the Seattle Department of Transportation calculated that 70% of Seattle households lived within a 10-minute walk of very frequent transit service, defined more stringently than that state threshold with 10-minute headways during peak hours.

A partial alternative, however, exists for cities that don’t prefer to fully pursue the sweeping zoning change scenario on lots outside of major transit stop overlays. Under the law, cities could opt out of the requirement by adopting an average minimum density equivalent set by the city’s size. Even so, for all cities planning under the GMA with at least 10,000 residents, duplexes would be allowed on all lots zoned for detached single-family homes whether or not they adopt the minimum density equivalent.

Washington is not the first to pursue statewide zoning reform. Last fall, the State of California effectively ended single-family zoning when it signed into law State Bill 9, which permits duplexes (and in some cases triplexes and fourplexes) in all areas zoned for single-family housing. Aimed at facilitating “gradual density,” under the new rules, up to 700,000 new homes could be added across California, a number representing the proverbial drop in the bucket when compared to the state’s current 7.5 million single-family homes.

While the long-term impact of SB 9 on the Golden State remains to be seen, it did move the needle a bit further forward in the fight to end exclusionary zoning than a bill passed in 2019 by the Oregon state legislature that requires cities with more than 10,000 residents to allow duplexes in areas zoned for single-family homes. That bill also increased density allowances in the Portland metro area to include triplexes, fourplexes, and courtyard apartments.

Increasing residential density in the Evergreen State

Washington’s HB 1782 has some features that make it unique from the approaches taken by California and Oregon.

The first important feature to point out that HB 1782 only pertains to cities planning under the GMA with populations of 10,000 or more residents. That leaves out smaller and often wealthier cities and towns like Woodway, Hunts Point, and Medina as well as other urban growth areas in GMA counties and non-GMA code cities and towns. Thus, while the majority of the state’s most populated areas would be forced to comply, unincorporated areas that have already been experiencing the impacts of suburban sprawl and smaller communities would be exempt.

Another notable feature of the bill is the provision it makes for cities planning under the GMA to forgo the prescribed single-family zoning changes outside frequent transit areas by adopting an alternative based on an average minimum density equivalent. Back in 2018, former Senator Guy Palumbo (D-1st District) introduced a minimum density bill focused around transit that failed to garner support. The minimum density equivalent requirement in HB 1782 works a bit differently than Palumbo’s proposal. Instead of requiring to nodes of density centered around transit, HB 1782 would establish baselines for minimum density equivalents based on city population size, but otherwise grant cities considerable freedom in how they fulfill the density requirement.

As the state’s only city with a population topping 500,000 residents, Seattle would have to “alter local zoning to allow an average minimum density equivalent to 40 [homes] or more per gross acre across the entirety of the city’s urban growth area.” While that requirement might appear steep, using content from the book Visualizing Compatible Density for reference, that amount of housing could be visualized as “urban townhouses and live-work units served by underground parking and containing private patios and a centralized, shared courtyard space.” Thus, a fairly moderate density scenario.

However, some ambiguity exists in the language around what city land would be included in the count toward the density equivalent. Hammering out that detail will provide more clarity as to how much residential density would be required under the alternative.

It’s also important to highlight use of the word “average” in the context of the rules. Although the law would allow for duplexes to be built in all single-family zones in the city, by averaging out its zoned density to meet the minimum requirements, Seattle could leave at least some single-family zoned areas relatively untouched. Such an approach to growth could perpetuate existing land use patterns that have funneled growth in urban villages. In an attempt to mitigate this outcome, the HB 1782 mandates that cities “adopt findings of fact demonstrating that actions taken to implement that average minimum density will not result in racially disparate impacts, displacement, or further exclusion in housing.”

Seattle will likely find it difficult to make the case that preserving exclusionary zoning would not come at a cost. A study completed by PolicyLink for the City of Seattle last year was unequivocal in its findings on the negative impact of single-family zoning on racial equity.

Given its racist origins, single-family zoning makes it impossible to achieve equitable outcomes within a system specifically designed to exclude low-income people and people of color.

In order to advance racial equity at the scale codified in Resolution 31577, the City must end the prevalence of single-family zoning. This will not only create much-needed additional housing opportunities in high opportunity neighborhoods for low-income residents, is also a reparative approach with the potential to create intergenerational economic mobility for BIPOC Seattleites.

PolicyLink Report on Residential Zoning for the City of Seattle , 2021

In an effort to further limit potential negative consequences arising from zoning changes, HB 1782 also requires that cities adopt anti-displacement measures within nine months of implementation.

Other Washington cities that decide to opt for an average minimum density equivalent would receive lower density requirements tiered by size. For example, cities like Spokane, Tacoma, Vancouver, Kent, Everett, Renton, Spokane Valley, and Federal Way, which each have over 100,000 residents, would receive an average minimum density equivalent of “30 [homes] or more per gross acre across the entirety of the city’s urban growth area.”

The number would continue to dip for cities with lower populations: 25 homes per gross acre would be required for cities with 20,000 to 100,000 residents; and 15 homes per gross acre for cities with fewer than 20,000 residents.

In order to avoid potential barriers arising from design review, environmental review, and permitting processes, HB 1782 is explicit that cities must use same standards and processes for missing middle housing (e.g., duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, and courtyard apartments) that are used for detached single-family dwellings.

Another aspect of the bill worth mentioning is that it provides a safe harbor provision for jurisdictions implementing the laws. Actions taken under the laws would be fully exempt from environmental review (State Environmental Policy Act) appeals. That’s a big deal because it would eliminate a lot of red tape and delays that could be created in the courts. As has been well documented, opponents to small projects like the Burke-Gilman Trail “Missing Link” have managed to tie Seattle up in the courts for years over the adequacy of environmental review documents and baseless assertions. So closing that as an adversarial avenue would help realize the benefits of the laws sooner and ensure certainty for all.

In regards to parking, cities cannot require off-street parking for missing middle housing within a half-mile of a major transit stop.

For developments that do not fall under the major transit stop umbrella, only one parking space per lot could be required on lots smaller than 6,000 square feet, and no more than two off-street parking spaces per lot could be required for missing middle housing constructed on lots greater than 6,000 square feet.

As a whole, for cities planning under the GMA, the bill would result in substantive land use changes. It will still need to work its way through the House and Senate for approval, so it’s possible for significant provisions in the bill to change as part of the negotiation process.

To recap, the bill would make the following changes:

- For cities with between 10,000 and 20,000 residents planning under the GMA, duplex zoning replaces single-family zoning citywide. Such a city may opt to allow for other types of missing middle housing (e.g., triplexes, quadplexes, and courtyard apartments).

- For cities with at least 20,000 residents, within a half-mile radius of major transit stops, sixplex zoning essentially replaces single-family zoning and parking minimums are voided. Cities opting for an alternate minimum density plan must still abide by this condition.

- For cities greater than 20,000 residents, in areas not located within a half-mile of major transit stops, fourplex zoning essentially replaces single-family zoning citywide unless the city adopts a citywide minimum density measure laid out in the bill. Parking minimums are capped at one parking spot per lot, or two for larger lots (6,000 square feet or more).

- If Seattle chooses this option, it must hit a 40 dwelling unit per acre threshold with its rezone plan across the city.

- Cities choosing a minimum density alternative outside major transit stop areas with a population between 100,000 and 500,000 must hit a 30 dwelling unit per acre threshold across their urban growth area with their alternate plan. This density is essentially on par with fourplexes. As of the 2020 Census, cities of this size include Bellevue, Tacoma, Everett, Vancouver, Kent, Renton, Kirkland, Spokane, and Spokane Valley.

- Cities choosing a minimum density alternative outside major transit stop areas with a population between 20,000 and 100,000 must hit a 25 dwelling unit per acre threshold across their urban growth area with their alternate plan.

Want to learn more? Join Representative Nicole Macri and Senator Rebecca Saldaña at The Urbanist’s January Meetup on Thursday, January 6, 2022 at 6:15pm. Full details and registration are available in the link below.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.