Puget Sound cities cannot continue to neglect sidewalks, bus routes, bike lanes, and multimodal trails when winter storms hit.

Today King County Metro finally (mostly) restored normal transit operations after an eight-day hiatus due to winter weather — albeit with a big dose of canceled trips. Metro had retracted bus service to a skeleton network of 60 routes leaving many riders without access to reliable transit. Sidewalks were also an icy mess across the region, which made it very difficult to get anywhere, especially for those without access to a car. Throughout this period, leaders urged people not to drive but failed to provide viable alternatives.

Such a severe blizzard and cold snap used to be fairly foreign to a city as temperate as Seattle, but it’s likely to be the new normal as climate change accelerates and temperatures extremes at both ends of the spectrum will get more commonplace. As a result, cities in Western Washington must get serious about preparing for winter storms like other northern cities do. We must devise a set of policies that ensure sidewalks are cleared, bus routes plowed and treated in a timely fashion, and bike lanes and trails are not forgotten so that everyone can get around the city. Week-long shrugs and advice to stay home will not cut it.

On the issue of sidewalk clearance, two main camps have emerged emphasizing either government or greater landlord responsibility using enforcement and education to rally property owners.

The public option camp believes the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) must take on responsibility for sidewalks because expecting property owners to clear sidewalks is unfair, hard to enforce, and will result in gaps where residents are not able to handle this responsibility. They point out to shoveling-related injuries, temporary shortages of shovels, and the not insignificant cost of deicer and road salt to bolster their case.

The greater property owner responsibility crowd, meanwhile, point out the cost of tackling snow clearance for the city’s entire sidewalk network would be expensive and would result in bottlenecks as one centralized entity is forced to prioritize limited resources across an 84-square-mile city. It would also let corporate landlords off the hook when they have ample resources to tackle the problem themselves. Mobilizing landlords to take responsibility for snow clearance offers the possibility of a faster response.

The ideal solution could well be a hybrid approach to snow and ice removal. Increasing resources at SDOT could fill in key gaps, such as sidewalk networks near transit stops and the bus routes themselves. But keeping the requirement and responsibility on landlords, especially with increased enforcement on the largest landholders, would avoid spreading SDOT too thin.

Rochester, New York offers a model for government intervention in sidewalk snow clearance with its policy of stepping in when four inches of snow falls. To fund the private contractors it employs, Rochester charges an embellishment fee on the property tax bill of the owner receiving the service. Some property owners would grumble, but it would be a system that ensures the job gets done. When less than four inches fall, Rochester puts the responsibility on the landlord and use fines to increase compliance.

Being a walkable city isn’t just a slogan or something to brag about in a real estate listing. It requires treating sidewalks as an essential public asset and ensuring they are passable 365 days a year. Owning property in a city entails this responsibility, just as the public stewards of our public right-of-way must devise policies that work in every season and don’t take a week or two off for inclement weather. Officials seem to be enthused about the 15-minute city concept, but ensuring residents can meet their basic needs within a 15-minute walk of home will require doing a better job of handling extreme weather.

It’s ultimately a matter of prioritization. Stockholm and other Swedish cities show a better way to handle snow clearance. Swedish authorities radically (from an American mindset anyway) clear sidewalks first and roads second. Officials reasoned many of the most essential trips were happening via walking or rolling, and residents who are disabled or do not own cars should be their first concern in ensuring mobility. Officials found the change was particularly beneficial to women, who made up the lion’s share of pedestrian trips.

After clearing sidewalks and emergency routes, snow clearance crews should focus on bus routes to reduce impacts on the transit network. That may allow Metro to restore full service sooner. If not, Metro would be wise to plan a more robust Emergency Snow Network so the drop off in service isn’t so steep. Skipping large swathes of dense neighborhoods isn’t sufficient or a viable solution, particularly when the emergency network is in effect for a whole week at a time.

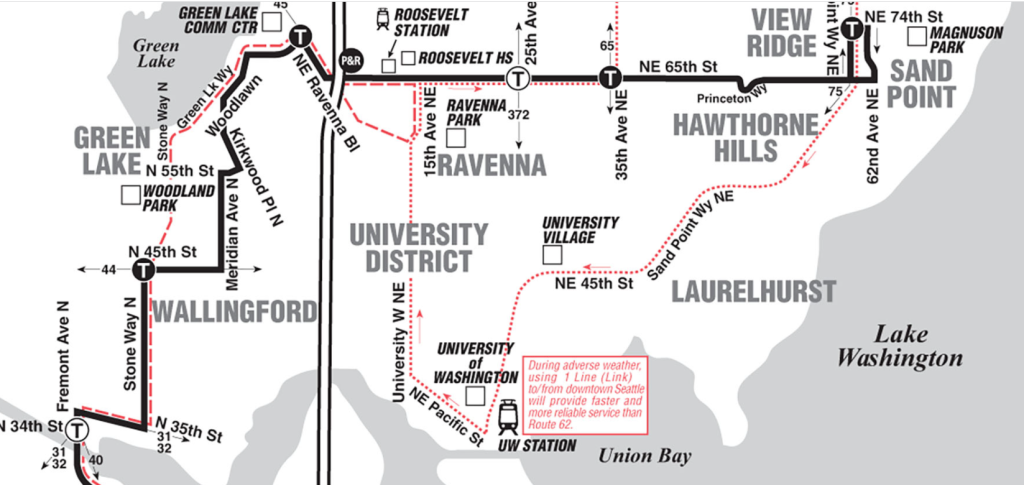

Take Route 62, for example, it skips most of Wallingford and Tangletown under its snow route as it takes the alternate path of a more direct East Green Lake Way route to Roosevelt, making no stops along the way. Transfers to Route 44 could piece together a trip for some, but also add more waiting time out in the cold. The 62 also uses Westlake Avenue instead of Dexter Avenue, making it tougher to get around for people living on hilly Dexter. It’s a similar story for many routes all over the city; many people find themselves living farther from useful transit when the Emergency Snow Network is in effect.

Metro struggles to communicate the changes, oddly choosing to use clunky PDFs to note snow route information rather than a format that is easier to navigate on mobile. From what we experienced, no automated announcements were on buses letting riders know about route changes and few bus drivers made the announcements themselves, which is understandable given the icy conditions demanding their full attention. To make matters worse, Metro’s real-time arrival systems had interruptions and were sporadic all week, which left riders in the dark on how soon their bus would arrive. Some bus stops (like one of the skipped 62 stops) would still display arrival information for buses that were never going to be coming due the alternate snow routing. In short, service quality deteriorated far more than the weather conditions alone dictated.

All in all, the region must make real preparations for snow emergencies. Acting surprised every winter is quickly growing old.

The editorial board consists of Natalie Bicknell, Stephen Fesler, Shaun Kuo, Ryan Packer, and Doug Trumm.

The Urbanist was founded in 2014 to examine and influence urban policies. We believe cities provide unique opportunities for addressing many of the most challenging social, environmental, and economic problems. We serve as a resource for promoting and disseminating ideas, creating community, increasing political participation, and improving the places we live.