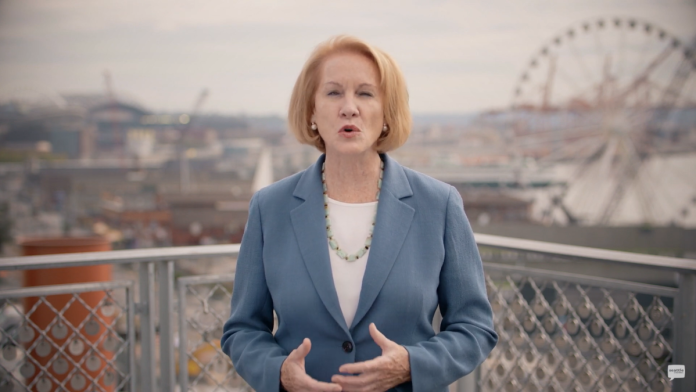

Today is Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan’s final day in office and attention is turning to her legacy as she passes the baton to her ally and friend Bruce Harrell. Annual polls gauging the share of voters who think the city is on the wrong track registered new highs in the final year of her administration, but the bulk of that blame was focused on the City Council. In particular, voters appeared frustrated with the city’s approach to homelessness and public safety.

Due to Seattle’s strong mayor form of government, that approach is by and large determined by the mayor. Mayor-Elect Bruce Harrell is pledging to overhaul how the City handles these issues even though he didn’t articulate many specific changes and his campaign platform was very similar to Durkan’s. Also, Harrell’s backers were very similar to Durkan’s, and his administration includes many holdovers from the Durkan administration, most notably Tiffany Washington, who he appointed to be Deputy Mayor of Housing and Homelessness and had also worked on the issue for Durkan.

Early warning signs

Early on in her administration, The Urbanist sounded the alarm that Durkan wasn’t living up to her campaign promises, lofty rhetoric, or espoused values. Despite running as a transit champion, in her first few months in office Durkan halted the Center City streetcar project, shelved three planned RapidRide bus projects (all of which remain in limbo), and delayed or killed several protected bike lane projects. She constructed just 73 of the 1,000 tiny homes she promised in her first year, and will have completed only 295 by the end of her term. Those delays and letdowns led me to opine she deserved a “D” for her first year in office. By 2020, it was readily apparent we had a failed mayor on our hands.

Wayward homelessness policy

Homelessness continued to climb under Durkan’s tenure. Mayor Durkan’s homelessness policy was largely a continuation of policy implemented under her predecessor, Ed Murray. The encampment sweeps continued as promised, but lo and behold moving encampments didn’t magically solve the problem or cause permanent housing for homeless folks to drop like manna from heaven. Durkan’s administration “cleared 50 homeless encampments this year alone, including more than 30 inhabitants of a camp in Green Lake Park earlier this month,” Sarah Grace Taylor reported in The Seattle Times. Even with those sweeping efforts, frustration with visible homelessness remained very high during the election season.

Like her predecessors, Durkan pressed for a regional partnership rather than adding new major revenue sources at the city level. Durkan did succeed in establishing a Regional Homelessness Authority, but that entity has been slow in getting rolling and came with no ongoing funding commitments from the other cities in the county.

As a result, Seattle continues to foot most of the bill for the whole county’s homelessness response while now having less control over how it is spent. It’s possible the regional authority could pay dividends in time if other cities step up with major new investments in affordable housing and homelessness services. But, for now, it’s too early to tell what the impact will be and it’s hard to count the new authority as a success in and of itself. Marc Dones appears to have been a good hire as the authority’s CEO, but the task is tall, as demonstrated by eight cities opting out of the County’s Health Through Housing initiative, which aims to raise $400 million backed by a 0.1% sales tax hike to build 2,000 homes for homeless people. Among the opt-outs are some the largest cities in the county, including Bellevue, Renton, Kent, and Issaquah.

Covid response

Mayor Durkan pledged Covid response would be the focus of her final year and has staked her legacy on that issue in interviews with The Seattle Times and KING-TV. Seattle has fared better than most other American cities, with fewer Covid cases and deaths and one of the highest vaccination rates. However, the Omicron wave is cresting right as Durkan leaves office and taking daily case counts to new heights, which casts some doubt on whether the pandemic is in check and present challenges to her successor.

Moreover, while the City’s vaccination effort was commendable, the mayor turned down the Biden Administration’s generous offer to cover 100% of the costs to put homeless people up in underused hotel rooms as a way to offer Covid-safe shelter during the pandemic. Even after relenting, Durkan slowwalked the program despite strong support on Council. California used the program to offer thousands of rooms to its homeless residents, but Durkan’s interference obstructed a similar rollout here, and their excuses are pretty flimsy, as Erica Barnett detailed.

Affordable housing and shelter

Another instance where Durkan fought a strange turf war rather than simply do the right thing by homeless people was when she tried to force Seattle Public Schools to stand up their own navigation team to clear an encampment near an elementary school in Bitter Lake. Using school funds for such a purpose seemed odd, but she was intent on offloading some costs on the district. Harrell even held a campaign event with the Bitter Lake encampment as a backdrop, saying he’d act decisively to make this problem go away in some not fully fleshed out manner that would involve consequences, just not any specific ones he mentioned during the campaign.

Upping the ante and echoing the ill-fated Compassion Seattle ballot initiative, Harrell has promised to deliver 2,000 units of emergency housing in his first year. Harrell may succeed in making significantly more headway on that goal that Durkan made on hers, but we could be in déjà vu territory.

The Mayor’s Office has sought to explain the missed campaign promises on housing by saying it was a conscious decision to pivot away from tiny houses to enhanced shelter once she got into office and assessed needs. Perhaps, it’s fine for a mayor to make bold promises on the campaign trail — not to mention criticize an opponent who suggested housing is a human right — and then turn around and operate much differently in office.

Mayor Durkan points to $2.5 billion being invested in affordable housing under her watch — $547 million of that City dollars via the Office of Housing — which will either create or preserve 7,600 rental housing units and permanently affordable homeownership opportunities, the Mayor’s office said. But the mayor also opposed the largest new source of affordable housing founding via JumpStart Seattle plan and sought to divert JumpStart revenues away from housing. Efforts to expand the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program to more parts of the city languished under her tenure and she delayed a racial equity study on the topic for years. The MHA program has emerged as the city’s top source of affordable housing revenue so expanding the program could further ramp up production. King County’s affordable housing task force reports that the region must produce 244,000 affordable homes by 2040 to solve the housing crisis. So 7,600 units isn’t going to cut it and isn’t cause for complacency.

Climate mayor?

The other issue that Durkan had sought to build a legacy around is climate, but the city still finds itself well off course from its climate goals. Under Durkan, no major new initiatives got off the ground. In 2018, Durkan pledged to implement road pricing to reduce Downtown congestion and pollution during her first term. She secured a $1 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies to do an initial study; however, after dragging her feet and never bringing forth a policy proposal, the mayor announced this spring she was pivoting to an “electrification blueprint” and abandoning the Downtown cordon pricing plan she had floated. This electrification blueprint now is in Harrell’s court and he seems very interested in electric cars, but the future of pedestrianization efforts, protected bike lane projects, and a promised emission-free zone remain very uncertain.

Occasionally, Durkan would say the right things emphasizing transit, street safety, and climate action in speeches, but the rhetoric was rarely put into swift action. For example, she abandoned important safety upgrades on Seattle’s fourth most deadly street: 35th Avenue SW. While Durkan did greenlight lower speed limits on arterial streets citywide after two girls crossing the street were injured in a crash in the Rainier Valley and advocates rallied behind their cause. But the accompanying street design changes were fairly minimal and some only lasted as long as the lifespan of a flexpost on a dangerous street, which is to say not long. And as a result pedestrian deaths have continued to climb under her watch.

Cities that have gotten real results implementing Vision Zero policies to eliminate traffic deaths have done so with design changes and major investments in walking, rolling, biking and transit service, not just lower speed limit signs and rhetoric. Hopefully, her successors will be more willing to commit.

Blaming the Council

Another frequent talking point from Durkan and allies (including the incoming Harrell administration) is that the Council is not collaborative and has obstructed and hamstrung her administration. Nonetheless, it’s clear her administration was hampered by self-inflicted wounds and its own vacillation, too. Scapegoating the Council for a lack of executive direction is unfair and inaccurate. The Council often pursued popular policies that she opposed, such as taxing big business to fund housing for homeless folks, or waited and waited and waited to get policies or direction from her office.

Secrecy, deleted texts, and coverup

Another hallmark of the Durkan administration was secrecy and one legacy is the ongoing litigation stemming from firing whistleblowers who blew lid on her coverup of ten months of deleted public records. This coverup helped bury evidence that could have support the push to recall or impeach Durkan in 2020. The state supreme court dismissed a recall effort against Durkan, but let it proceed against socialist Councilmember Kshama Sawant — who survived by just 310 votes. Beyond public records violations, journalists have often encountered difficulty in getting timely responses from the Durkan press shop and interference when seeking comments directly from City departments, which has further shrouded the administration in secrecy.

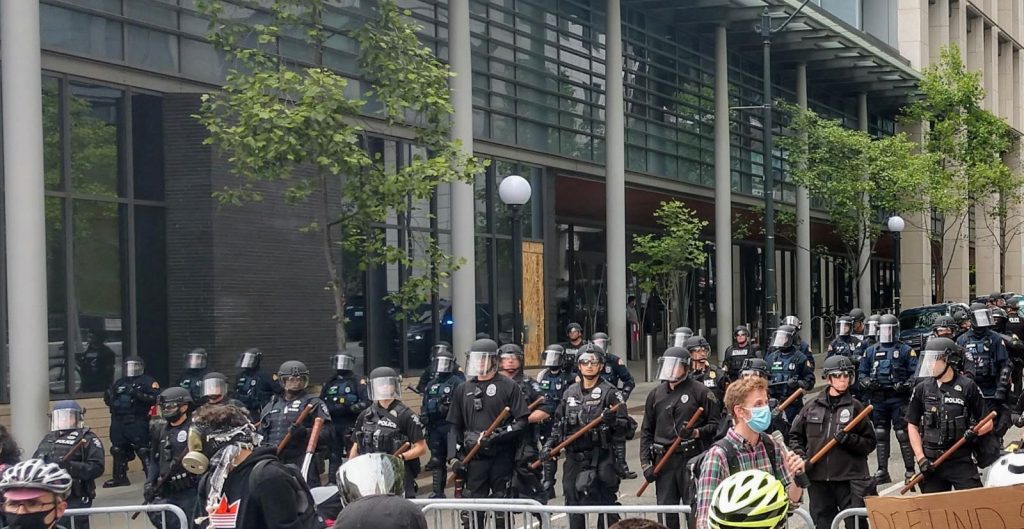

Tear Gas Jenny’s crackdown

And of course there’s the tumultuous summer of 2020 when Black Lives Matter protests were widespread in the streets. Mayor Durkan responded to the protests by doubling down on tear gas and a brutal police crackdown that included pepper spraying children, blast balling journalists and medics, and general chaos at the top. Siding with the police at every step, Mayor Durkan argued against a ban on chemical weapons and joked about a Thelma and Louise moment with Police Chief Carmen Best. Best resigned in July 2020, citing frustration with budget cuts and a refusal to lay off police officers, even those who were on the Brady list for lying. Mayor Durkan opted against running for reelection with her approval numbers suffering but ultimately has survived to the finish out her term.

Beyond crackdowns on protests, the mayor’s solution for the summer of protests was to promise a $100 million annual investment in communities of color, which led to some fuzzy budget math and double counting of past investments. She sought to direct those investments through a hand-picked task force despite many Black and Brown leaders demanding a more democratic and representative system, with 19 leaders declining to participate. She has obstructed a parallel participatory budgeting process that leaders with Solidarity Budget coalition have demanded.

Highlights

Here’s some of the highlights from Durkan’s term:

- She promised to implement road pricing in first term, then walked away from that pledge.

- Halted streetcar construction, spread (mistaken) doubts the streetcars would not fit the tracks, recommitted to the project after independent review confirmed the viability of the project and robust ridership projections, canceled it again citing budget impacts from the Covid recession, restarted planning again, and left it in limbo with a funding gap for the next mayor.

- Negotiated a police contract that rescinded accountability measures passed the previous year, gave officers generous package of raises and retroactive pay, and punted on the issue of controlling overtime costs and outside work.

- Negotiated down the 2018 head tax and added a sunset clause, claiming to have brokered a compromise with the business community, who went to war anyway and pursued a repeal campaign, which pressured the City Council to repeal the tax.

- Violated open meeting and public records law to negotiate that head tax compromise deal, and her team was ordered to get refresher training on public records law.

- Opposed the JumpStart Seattle corporate payroll tax in 2020 and vetoed the spending plan. Council overrode that veto.

- Raided JumpStart revenue (which she had opposed raising) to fill holes in her budget.

- Skipped the meeting when a precinct commander apparently decided to abandon East Precinct without telling the police chief after growing frustrated with being asked to try new deescalation-minded tactics at Capitol Hill protests.

- Deleted ten months worth of text messages to conceal how she responded during this sensitive period, including the East Precinct incident. This is despite the aforementioned court-ordered refresher training on public records law compliance.

- Fired the two whistleblowers who revealed that the Mayor’s Office was covering up the deletion of said text messages, which has triggered a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against the city.

Even in places where Durkan could point to progress, some of it has already been undone. One such example is appointing a competent and steady-handed leader at the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) in Director Sam Zimbabwe 15 months into her term after a lengthy talent search. Zimbabwe helped right the ship, improve project delivery, and weather a number of crises, such as the emergency closure of the West Seattle Bridge due to cracking. He also rolled out lowered 25 mph speed limits on arterial streets in 2019. One of Mayor-Elect Harrell’s first acts was to fire Zimbabwe and start the leadership carousel all over again.

Whether Bruce Harrell will be a different kind of mayor remains to be seen. He’s promised a collaborative, data-focused approach, but the devil is in the details, of which there have been few. On transportation, Harrell has said he wants to recognize the role of cars and doesn’t want to lead with bikes. These vague, but concerning statements could signal a reversal. Or perhaps the data (such as climbing traffic deaths) will ultimately be persuasive.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.