Paris is already home to its famed Métro, which holds the honor of being the second busiest metro system in Europe after Moscow. But an ambitious expansion project called the Grand Paris Express will double both the reach and ridership of the Parisian Métro within the next decade. After its completion, commuters will be able to travel between destinations within the Parisian Metropolitan area (Île de France) without having to travel into the city of Paris itself to first make a transfer. The Société du Grand Paris describes the expansion as a “fundamental rethink, redesign and focus on the public transport network on the scale of the metropolitan area.”

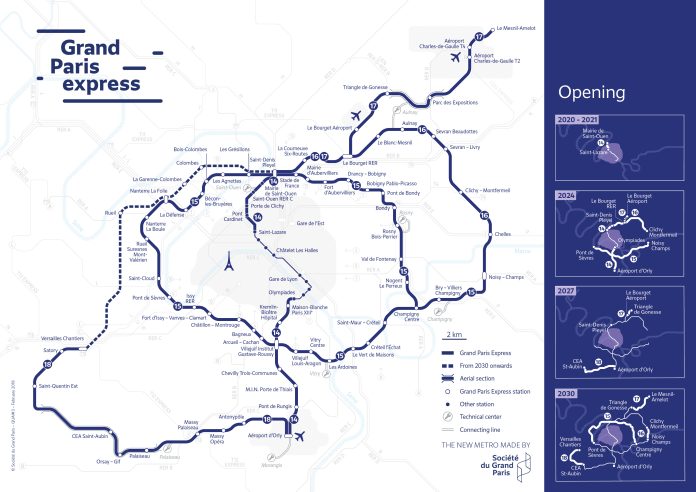

To be brief, Grand Paris Express is a radical network expansion aimed a creating a “polycentric” transit system, by lengthening some existing Métro lines and adding four new ones that run in interconnecting rings around metropolitan area.

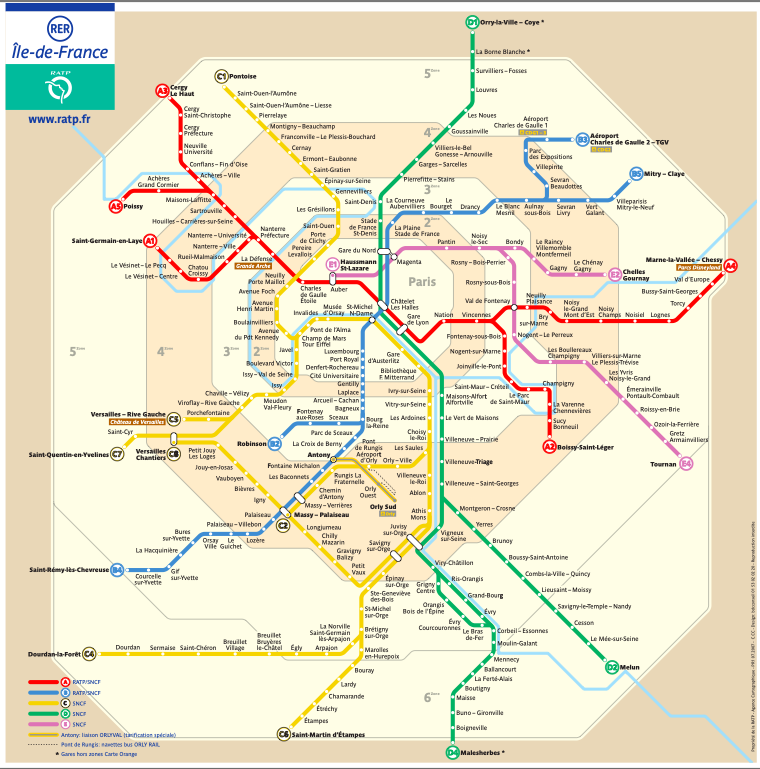

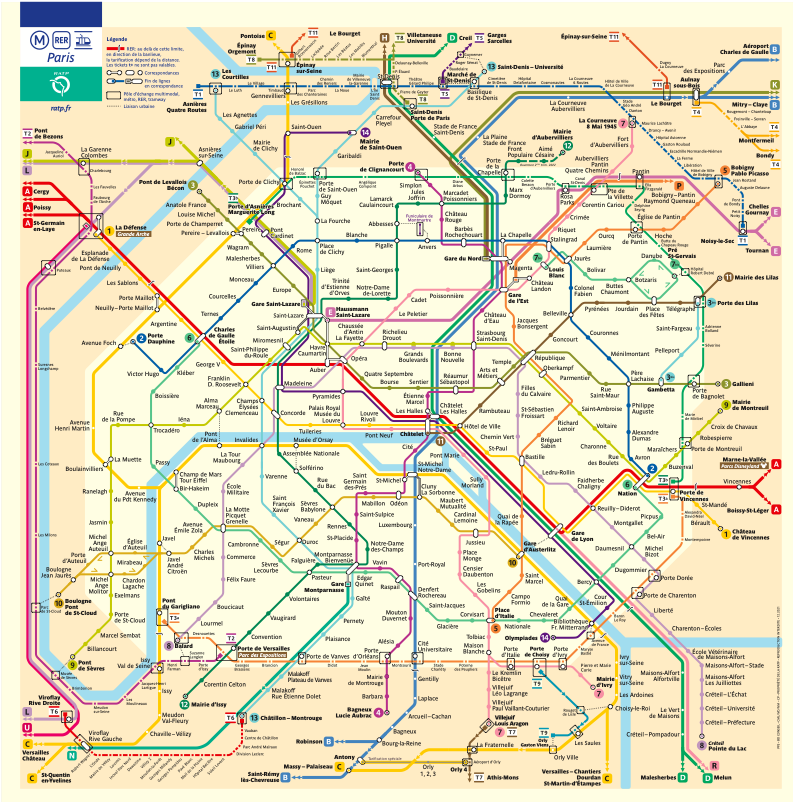

To get a sense of how transformative the project will be, let’s first look at Paris’s existing public transportation network. The current network is made up of different elements which each compliment each other and serve meet slightly different needs. Within the city of Paris, the Métro and, to a much lesser degree, tram system provide very comprehensive coverage to transit riders. Buses are also integrated into the network, and move people both within the city and its suburbs.

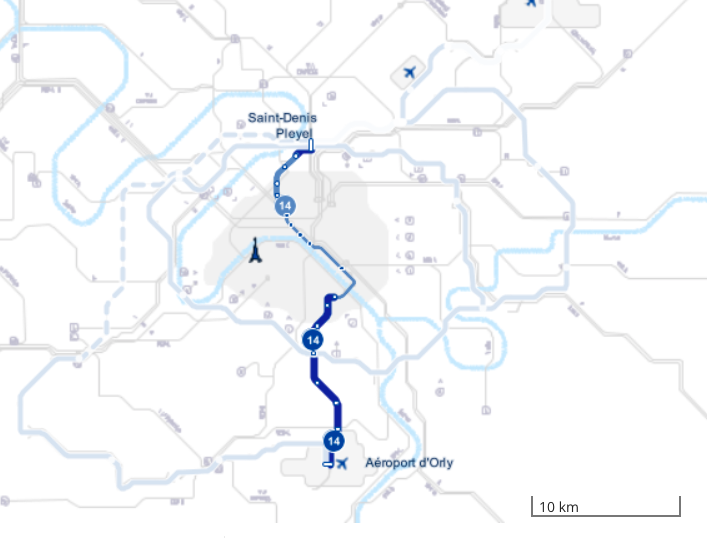

However, the two primary modes of rail transportation used by people living Parisian suburbs are the RER (Réseau Express Régional) and Transilien, a play on the word “Francilien” used to describe residents of the Parisian suburbs. Both rail lines primarily operate to move riders into the city, and as a result, traveling to destinations within the suburbs can be long and challenging. For example, a student or researcher traveling from Orly Airport to the Paris Saclay University Campus has to travel for over an hour under the current conditions. Once the Grand Paris Express expansion is completed, the trip will take about 15 minutes.

As the Parisian suburbs have grown, the need to move between them via transit has increased as well. The city of Paris has a population of 2.2 million people. By contrast, an estimated 10.5 million people live in Parisian suburbs. But because of limited transit connections, suburbs fewer than ten kilometers outside of the Parisian city limits can feel worlds away from the city center.

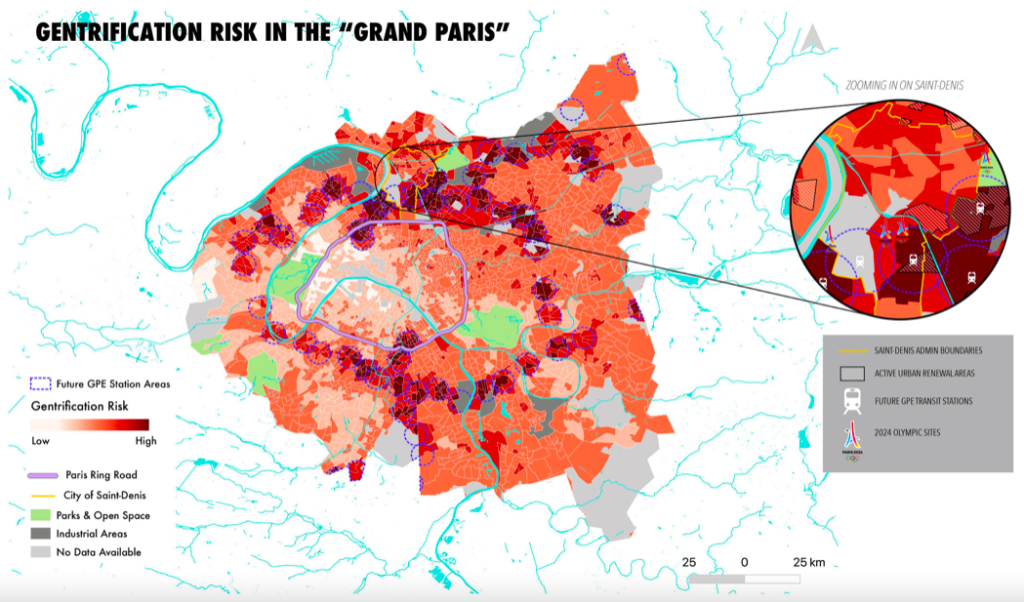

While the Parisian suburbs include a spectrum of poverty and wealth, by and large they are home to many of the metropolitan area’s poor and working class communities and have higher numbers of residents who are immigrants and people of color. In recent decades, tension in marginalized communities has surfaced as riots and debates over how to create a more integrated and equitable society loom large in French media and politics. The Grand Paris Express expansion project will bring new transit connections to many communities making it easier for people travel within the suburbs for work, school, and more.

Some, however, caution that by increasing the transit connections to central Paris, lower-income suburbs will experience the gentrification that has impacted much of the city. A gentrification risk map created by Manon Vergerio using median area incomes and property values to assess displacement risk aims to illustrate where the impacts of gentrification resulting from the Grand Paris Express project may be most prominent.

However, defenders of the Grand Paris Express project say that plans to engage in transit oriented development, most of which will be built by private developers, in the station areas will result in more affordable housing and more car-free lifestyles. Moreover, France’s forward-thinking housing policy requires local jurisdictions to increase social housing and plan for growth. Paris is on track to hit its target of 25% social housing by 2025, and surrounding cities have similar mixes, with social housing composing about one-third of the new housing built in Greater Paris over the past decade. Thus far, 70,000 new homes are slated for construction within a half-mile of the new stations.

Back and forth dialogue between these two camps — one professing that the project’s topdown urbanism serves the elite at the expense of the poor, the other arguing that ambitious planning at this scale is the best way to broadly reduce reliance on cars for transportation, increase high-opportunity housing, and unify the metropolitan area — opens up important questions relevant to all city planning.

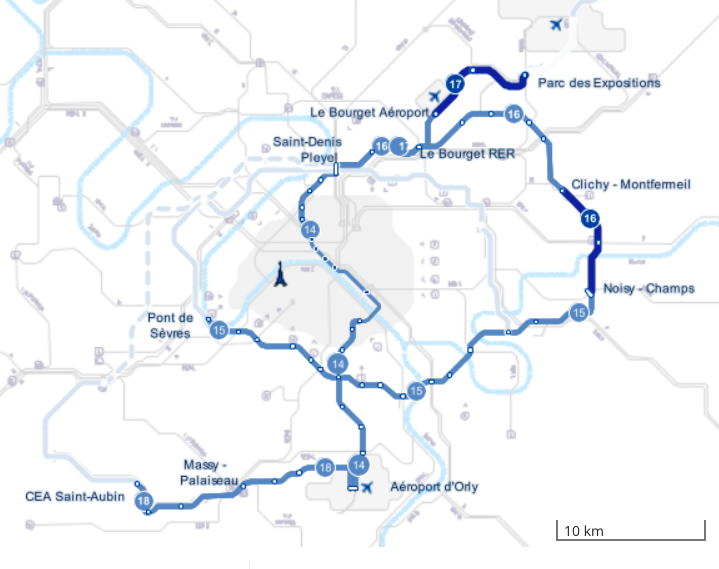

The Grand Paris Express project broke ground in 2018, and it is progressing on time. If all continues to go as planned, by 2030 the system will have added 68 new stations and 200 kilometers (124.3 miles) of new railway lines, 90% of which will be built below ground. Once the system is up and running trains will arrive every two to four minutes at peak hours, and the expansion will serve a projected two million passengers daily.

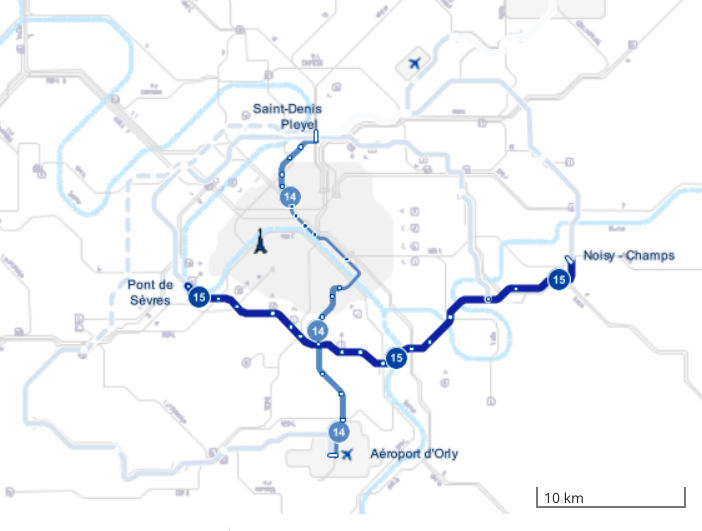

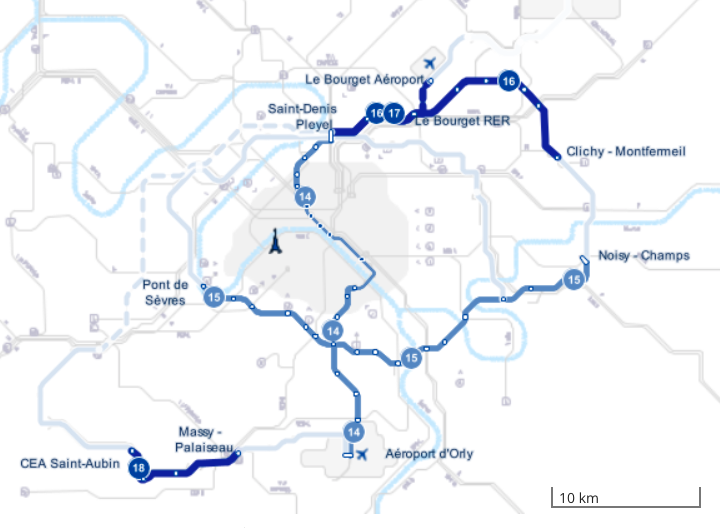

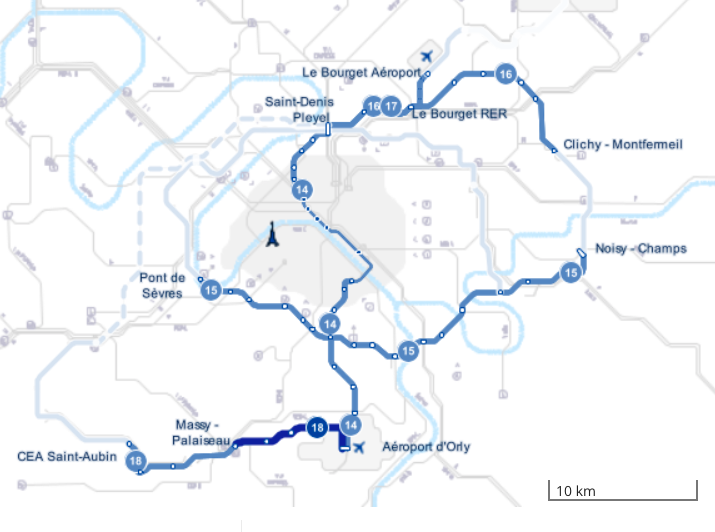

The first phase of the project is estimated to be complete in 2024 for the Summer Olympics in Paris, after which the expansion will grow year by year until its completion in 2030. Scroll through the slideshow below to see the system expand in phases.

All of this work has come at a hefty price tag. A total of €35.6 billion has been earmarked for the Grand Paris Express development, including a provision of €7 billion for risks and contingencies, putting the full cost at roughly €42 billion ($54.34 billion). To put that figure in perspective, the Seattle Metro region’s Sound Transit 3 expansion, which at 62 miles is arguably the largest transit system expansion in the United States, was estimated to cost $53.8 billion when it was approved by voters in 2016. Since then costs have increased, resulting in a hybrid realignment plan being passed in the summer of 2021 aimed at creating cost savings.

€42 billion is a significant investment; however, currently one million vehicles per day use the Périphérique, a 35-kilometer ring road separating Paris from the suburbs every day. Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo has been working hard to reduce the amount of cars in Paris, and even announced the goal of making parts of the city center car-free by the end of 2022. If the transit oriented development that accompanies the Grand Paris Express defies its naysayers and proves to be more equitable than they predict, the massive transit expansion project may offer up a new blueprint for 21st century low-carbon city building.

It may also offer a political blueprint for convincing suburbs to embrace pedestrianization efforts and turn away from car dependency. Rather than resent Paris for turning formerly car-clogged streets over to people walking, rolling, and biking, Grand Paris Express invites Franciliens to hop aboard and join them.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.