Last week, Bellevue City Council approved a Land Use Code Amendment (LUCA) to allow for increased building density on a 60-acre site to the east of the future East Main light rail station. The unceremonious nature of Council’s vote to approve the LUCA at its last meeting of the year belied its importance as the culmination of eight study sessions, a years-long public outreach process, and thousands of work hours from planning staff. The 60 acres represent a fraction of the station’s 15-minute walkshed, which continues to include single family zoning farther out.

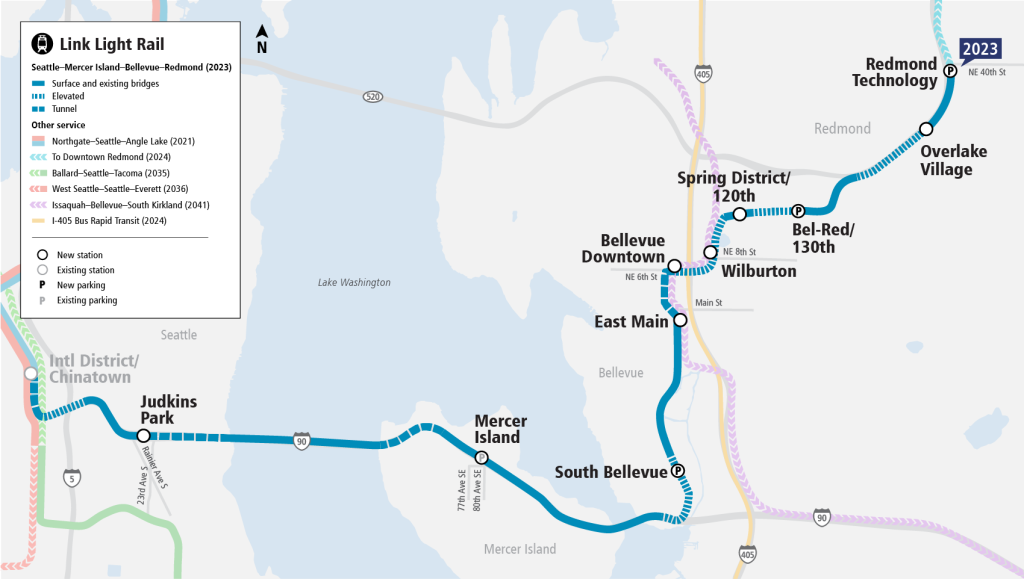

It’s no secret that Bellevue is experiencing a uniquely rapid employment growth, fueled in large part by Amazon’s and Facebook’s expansions into the city’s Downtown and Spring District neighborhoods, respectively. Because of prior work by planning staff and Council, these areas have land uses that have been able to accommodate the demand. However, the low-density area around the East Main station has seemed comparatively unprepared for the opening of Sound Transit’s East Link Extension in 2023 — an event that will represent the largest paradigm shift in Eastside mobility since the opening of the first floating bridge. Because a light rail line is only as useful as the land uses around its stations enable it to be, this process by Bellevue City Council represented a one-time chance to craft policies that encourage the redevelopment of this site into a transit-oriented and mixed-use community.

While the zoning plans that arose from the LUCA process represent a step in the right direction, the fact remains that Bellevue is acutely in need of more affordable housing. Political leaders need to be ready to take bolder action to make the $3.7 billion investment in East Link light rail reap its full potential. Taking a close look at current plans for the future of East Main provides insight into how transit oriented development is currently unfolding in Bellevue and what can be done to make it better.

The Site

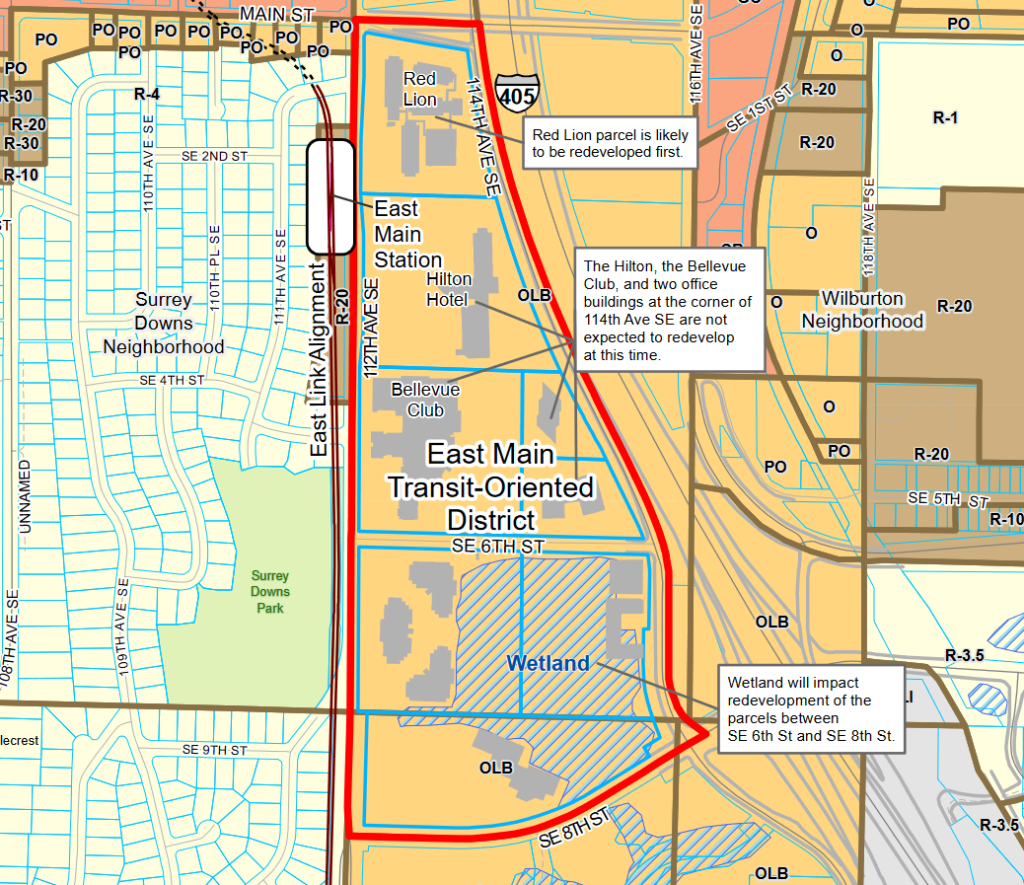

The East Main development site comprises the area between Main Street and SE 8th Street to the north and south, and 112th Avenue and 114th Avenue to the east and west, respectively. The site is bisected by SE 6th Street, which is a minor three lane road that provides vehicle access to some of the office complexes. It’s also the road that several conservative councilmembers had wanted to select as the preferred alternative for an additional I-405 access point (luckily this did not happen). The portion south of SE 6th Street is heavily populated by a wetland area, which restricts the amount of development that can occur on this section (another reason not to build a new freeway interchange nearby, perhaps).

The northern portion is comprised of five parcels – these are the ones closest to the light rail station and with greater development potential. The two northernmost parcels are currently hotels owned by Wig Properties, who featured heavily during the public outreach process. The Bellevue Club, a local membership-based athletics club located on the southwest corner of 112th Avenue SE & SE 6th Street, also provided their input at several junctures. Many Councilmembers and nearby residents regarded them as a community asset that should not be subject to all LUCA provisions, so exceptions were carved out for them throughout the process. For example, an expansion of the Bellevue Club on its parcel would not trigger minimum housing requirements like development on other parcels in the rezone would.

Multimodal transportation around the site is somewhat limited. To the east, 114th Avenue SE serves as part of the Lake Washington Loop bicycle trail and provides painted bike lanes most of the way on each side, but portions of these facilities towards the north turn into sharrows. Pedestrian travel between parcels is restricted, with no cross streets between them to provide easy access. Throughout 2020 and most of 2021, transit service along 112th Avenue SE was limited to King County Metro Route 240 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but Route 246 was recently restored as part of KCM’s fall service changes. Finally, the 186-stall Wilburton Park & Ride towards the southeast of the site provides quick access to I-405. East Main LUCA provisions would need to address both housing and transportation facilities to ensure this site has maximum utility as a multimodal development.

Land Use Code Amendment (LUCA) Discussions

Although this rezone process began years ago with the East Main Station Area Plan, the five most recent Council study sessions over the last six months represented an important juncture in the project. City staff collated stated priorities with stakeholder requests and technical considerations to create their recommendations for the site, which would then be subject to Council approval or modification. The study sessions also provided additional opportunities for stakeholders to drive the process in their favor — representatives of developer Wig Properties spoke at every study session to encourage various provisions that would make redeveloping the site more economically feasible. Unsurprisingly, these requests were not always in line with the most efficient ways to address key priorities of affordable housing and transit-oriented development, but it would ultimately be Council’s job to make these decisions on behalf of Bellevue residents.

Building Height & Housing Options

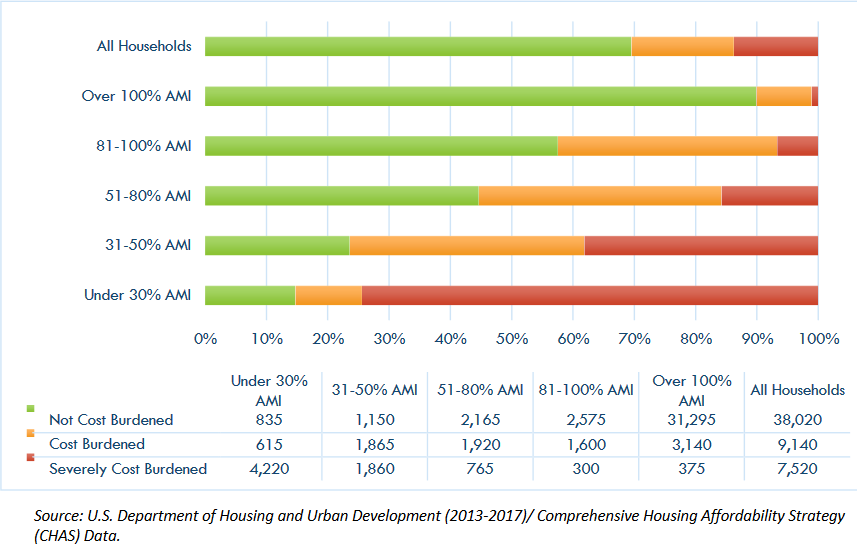

I’ll focus more on this later, but Bellevue, like every other city in our region, is experiencing an affordable housing crisis. This has been driven, in part, by a lack of commensurate growth in housing units as our city has enticed people with new jobs. With the shortage of housing units in the city in mind, Council expressed that providing housing at the East Main site would be a priority, with a particular emphasis on affordable housing.

Although there was some dissent from conservative Councilmembers, Council settled on maximum building heights of 300 feet (320 feet with mechanical components) with a minimum housing requirement of 35% in accordance with staff’s recommendation. Per their calculations, this would result in the creation of more than 1,500 housing units, of which approximately 87 would be affordable at less than 80% Area Median Income (AMI). Mayor Robinson, at a November meeting, also introduced a deed-in-lieu option that could open up possibilities for developers to partner with non-profit organizations to create deeply affordable housing. Nearly all of her colleagues supported her amendment.

In general, developers want to maximize the amount that they are able to build on a particular site, because it increases the ultimate return on their initial investment. Therefore, it was foreseeable that Wig Properties would advocate for greater building height, asking through testimony and discussions with staff for 400-foot maximums and lower housing requirements. This call for taller building heights and lower housing requirements ended up being a recurring theme during developer testimony across multiple study sessions. Although key stakeholders wanted fewer housing requirements, Council as a body held firm in mostly agreeing with staff recommendations (with some individual exceptions). However, they also decided to allow for developers to apply for deviations to the base code through a Development Agreement (DA).

FAR & Public Amenities

Although wonky, Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which is the ratio of a building’s total floor area to the size of the piece of land on which it is built, is important to understand because it’s central to defining the amount of development that can occur on a particular site. Effectively speaking, the higher the FAR, the greater amount of development that can occur on a particular site. City codes often also have provisions to allow for higher FARs for projects that provide public benefits: affordable housing, pedestrian amenities, and public art, to name a few. Developers, in general, will want higher FAR allowances, because this will mean they will be able to develop the site to a higher degree (and therefore get more bang for their buck).

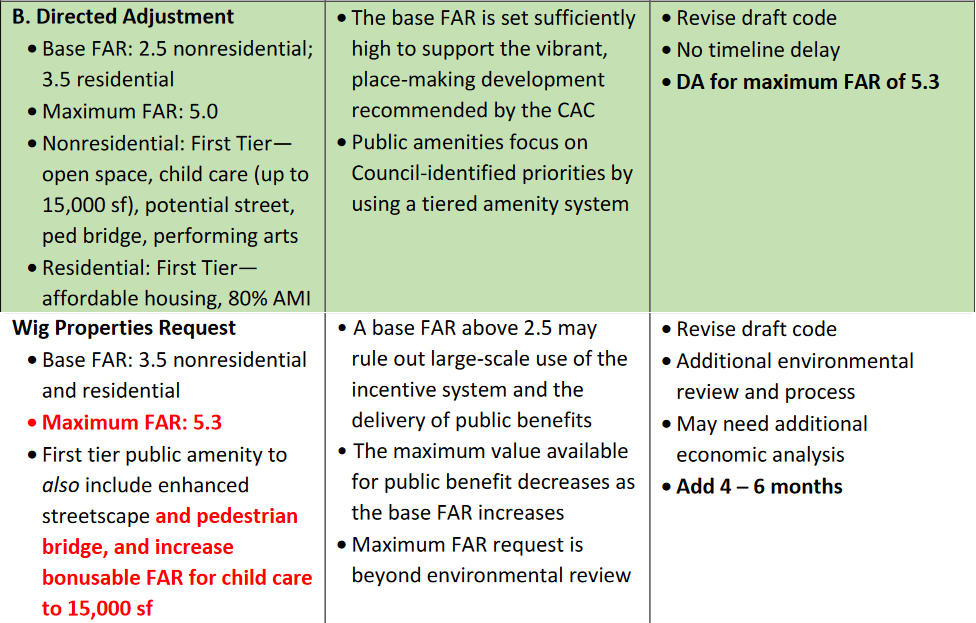

City staff’s recommendation to Council for East Main called for a base FAR of 2.5 for nonresidential development, 3.5 for residential development, and a maximum FAR of 5.0 if the developer contributes to public benefits. These provisions mean a couple things in practice: 1) residential development is subtly encouraged by allowing for a higher base FAR than nonresidential development, 2) in order to build up to the maximum 5.0 FAR, developers would have to provide the equivalent of 1.5 FAR and 2.5 FAR in public benefits for residential and non-residential development, respectively.

By way of comparison, Seattle’s Northgate rezone topped out at maximum height of 240 feet and a FAR of 7.0, a zoning which could fit more housing and/or office space per acre despite a lesser height limit (once those landowners develop anyway). Even Seattle’s Seattle’s Mid-Rise zones have a FAR of 4.5, meaning similar densities to what Bellevue has allowed via the East Main rezone, even without towers. With a FAR of 5.0, a 30-story tower could only consume about a sixth of a development site without tripping FAR requirements.

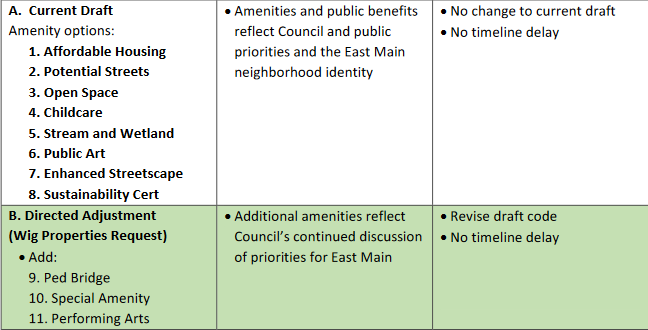

Wig Properties, in contrast, asked for the same base FAR of 3.5 for both residential & non-residential development, and an increase of the maximum FAR to 5.3. Staff cautioned that the latter provision would require additional State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) review and would extend the East Main LUCA process by four to six months to review, so this option never seemed seriously examined by councilmembers. However, several conservative members did express support for a base 3.5 FAR across both types of development. As noted in the above graphic, this would have removed the incentivization of residential development and restricted the amount of public benefit the city could obtain from projects. Deputy Mayor Nieuwenhuis ultimately joined the majority of his colleagues in supporting 2.5 nonresidential FAR, but Councilmembers Robertson and Lee still voted for 3.5. Throughout the LUCA process, Councilmember Lee in particular expressed his concerns with making sure projects would still be economically feasible and that regulations weren’t too onerous for developers.

Councilmembers also took several votes on adding different types of public amenities to the master list. Doing so gives developers more choice in what they can build to satisfy public amenity requirements for increased FAR, but if the list is too diluted, priorities that are very important (such as affordable housing) might not get built, with developers instead choosing other options. Ultimately, Council did go with a wide array of public amenities (pictured below) with lots of cross-pollination between progressives and conservatives on support for individual amenities. Time will tell on what effect these decisions will have on the character and use of the site.

Block Size & Streets

In contrast with the large blocks commonplace throughout Downtown Bellevue, an explicit priority of the East Main site was to incorporate smaller block sizes. This is generally best practice in transit-oriented areas, because smaller block sizes tend to mean smaller streets, which mean slower speeds that can more readily accommodate multimodal travel.

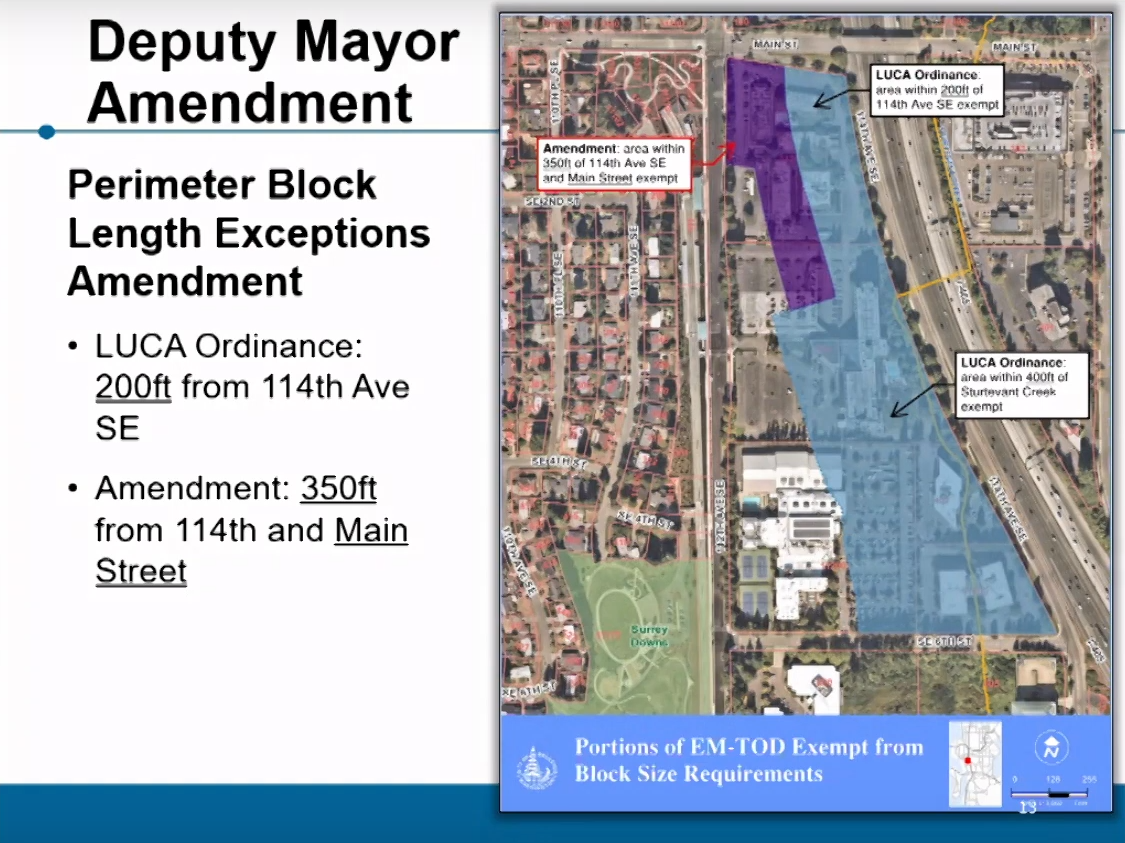

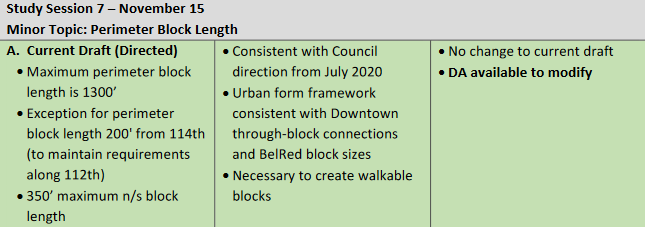

In a move almost comically antithetical to the whole purpose of this rezone, representatives of Wig Properties cited difficulties in providing walkable blocks because they reduce the ability to provide surface parking. They originally asked for all perimeter block length requirements throughout the site to be removed, and luckily, Council did not grant this request. However, newly-reelected Deputy Mayor Nieuwenhuis introduced an amendment at the December 6th meeting that would’ve extended the provisions of exemption on some of the site (pictured below). Under the originally proposed LUCA from staff, the areas in blue would be excluded from block perimeter requirements. Through his amendment, Deputy Mayor Nieuwenhuis proposed that the block size exemption be extended to the areas in purple to allow for the siting of a grocery store at the north of the site, which he argued would require a larger block size. He cited feedback received during the citizen outreach process about the need for a grocery store in the area as a justification for his amendment.

However, some confusion arose around whether his amendment would solely apply to grocery stores or all developments no matter the usage. At the beginning of discussion, Mayor Robinson asked him to clarify if the provisions would apply regardless of what was proposed at the site, or if the block length exemption would only apply if a grocery store was proposed, to which he answered the latter. Councilmembers Barksdale and Robertson, each at separate ends of the ideological spectrum, noted that the amendment as it was written in the packet would actually apply to all types of development. Therefore, although the amendment was presented as a way to encourage a grocery store being sited at this location, it would originally not have included a provision to ensure that a grocery store was included with a development project to get the exemption.

This made the amendment a non-starter for some councilmembers, who would only support it if it included a provision limiting the exemption to grocery stores. Staff expressed concern that tailoring language in the amendment to that requirement might not be able to be completed in time to allow Council to vote on East Main work before the end of the year. However, staff was able to return with the proper language and requisite research done before Council approved the LUCA, amendments included, at their December 13th meeting.

What’s Next & the Larger Context

Even with its imperfections, the provisions in this LUCA will create a site that is a net benefit to Bellevue. Aside from Councilmember Lee repeatedly trying to give the developers exactly what they were asking for at every juncture, councilmembers understood their role in balancing the needs for public amenities while making sure regulations weren’t cumbersome to potential development. It’s therefore only natural that Council and staff are proud of the literal years of work that have been embedded into this process. However, it’s important to temper the city’s pride with a sober examination of the remaining work to be done.

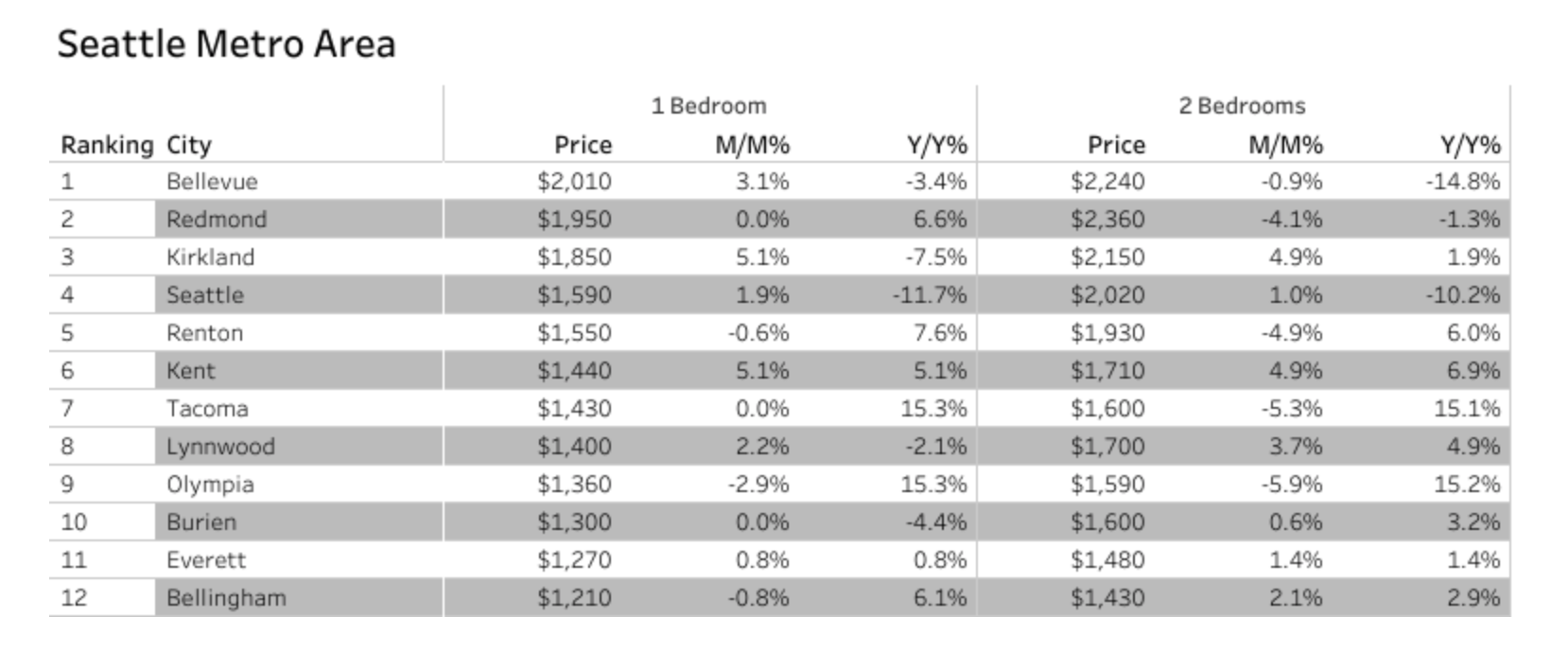

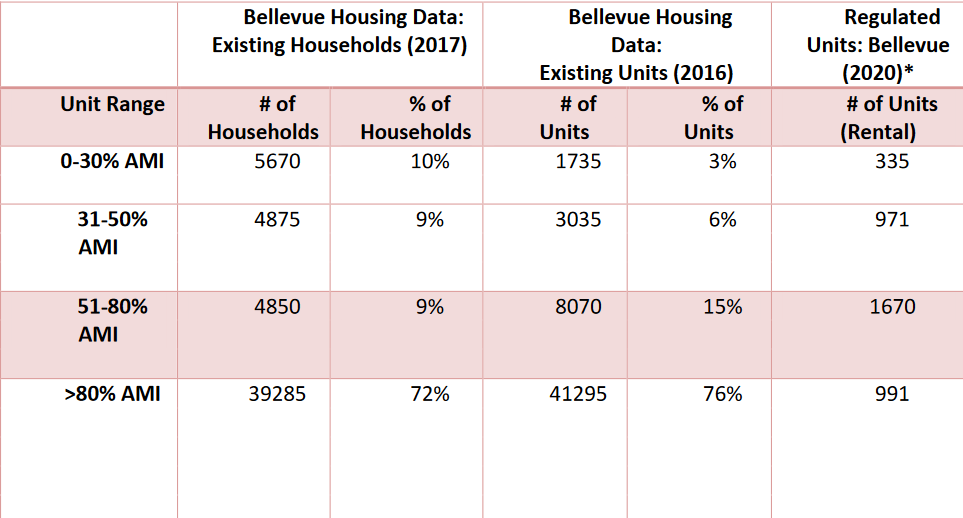

First and foremost, Bellevue is experiencing an acute version of our region’s affordable housing crisis. With mean rents for a one-bedroom apartment going for $2,010 as of June 2021, city residents are burdened with the most expensive rents in the state. Additionally, the currently available affordable housing stock is not adequately tailored to the actual needs of the community. As I’ve written about before, the city’s current goal of creating or preserving only 2,500 affordable units in 10 years is woefully not commensurate with the already-present need for affordable housing.

This is so important that I’d like to repeat it: in a city with the most expensive rents in the state and a current housing deficit of nearly 6,000 units below 50% AMI, its official ten-year affordable housing strategy only calls for the creation (or preservation) of 2,500 units across all affordability levels. Even if all of the estimated 1,500 units at the East Main site were mandated to be deeply affordable (note that current estimates put the number of affordable units at 87, and that includes 50-80% AMI housing), that would be just a drop in the bucket towards filling the gap in deeply affordable housing in Bellevue.

Additionally, although this planning work was completed before the opening of East Link light rail, actual redevelopment and construction at the site will almost certainly not be complete before the line’s opening. This lag will reduce the usefulness of light rail in being able to connect high numbers of people soon after its opening; therefore, we might need to be prepared for bad-faith arguments from light rail detractors if initial ridership numbers are lower than forecasted.

Similarly, upcoming planning work in the Wilburton and BelRed neighborhoods is not going to result in development that will arrive in time for light rail’s opening. Work for Wilburton still finds itself in the planning stages after a four-year pause, and there is still not a publicly available timeline for when BelRed work will begin. To Council’s credit, initial rezoning of the BelRed neighborhood began promptly after ST2’s approval in 2008. However, a quick ride through the area makes it abundantly clear that that LUCA has not resulted in the widespread redevelopment needed to make the most of the soon-to-open rapid transit line traversing it. Which exact provisions in that rezone have led to a lack of redevelopment will be the subject of Council deliberation, and analyzing what mistakes were made back then will be important, but that will need to wait as the subject of another article.

What this means, however, is that when riders depart from an East Link train at Wilburton or 130th Ave Stations in 2023, the above views of car dealerships and auto repair shops are what they’ll be greeted with. As noted in a recent Geekwire article, Bellevue has 1/15th the planners of Seattle despite having 1/5th the population. It’s therefore easy to wonder if this work could be accomplished more rapidly with more planning staff working concurrently on rezones in different neighborhoods. As Sound Transit 3 (and, an urbanist can dream, Sound Transit 4) get planned and approved, perhaps the city can learn from the delay and plan rezones with adequate time to have a redevelopment impact before light rail opens.

Finally, I’d like to acknowledge the narrowing (whether intentional or not) of the Overton window that’s inherit to this rezone process. As I and others have pointed out in previous articles, over 75% of the city’s land is currently zoned exclusively for single-family housing, creating an artificial scarcity that unnecessarily drives up home prices. Careful observers might notice the large swathe of single-family housing in the Surrey Downs neighborhood directly to the west of the East Main light rail station. Limiting rezones to just isolated sites or neighborhoods places additional pressure on city leaders to get key LUCA provisions exactly right in order to meet affordable housing goals and limits our thinking of what solutions are possible. With more widespread zoning reform citywide that would allow for a diverse mixture of housing types in all neighborhoods, it would be possible for policymakers to create more affordable housing options with one fell swoop, rather than over years of process and delay for each individual neighborhood.

However, since several conservative Councilmembers have expressed trepidation at this idea, it is likely that such action would need to happen at the state level. Perhaps state action through Rep. Jessica Bateman and Sen. Mona Das’s proposed housing bill can create headway on this front. Until then, it appears Bellevue will continue forward with the Bellevue Way — a political process that’s become a euphemism for lengthy consensus-building at the expense of the rapid policy implementation needed to meaningfully address its affordable housing deficit.

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.