Snotrac Coalition worries the plan won’t put enough growth equitably near high-capacity transit.

Snohomish County planning authorities have all but signed off on new growth targets. Early this month, the county’s regional planning body took final action in adopting specific jobs and population targets by jurisdiction. These targets will be used to determine how cities and the county update their policies and regulations in 2024 to accommodate growth over the next 20 years. Local city councils and the Snohomish County Council will still need to give final consent to the growth targets to make them binding.

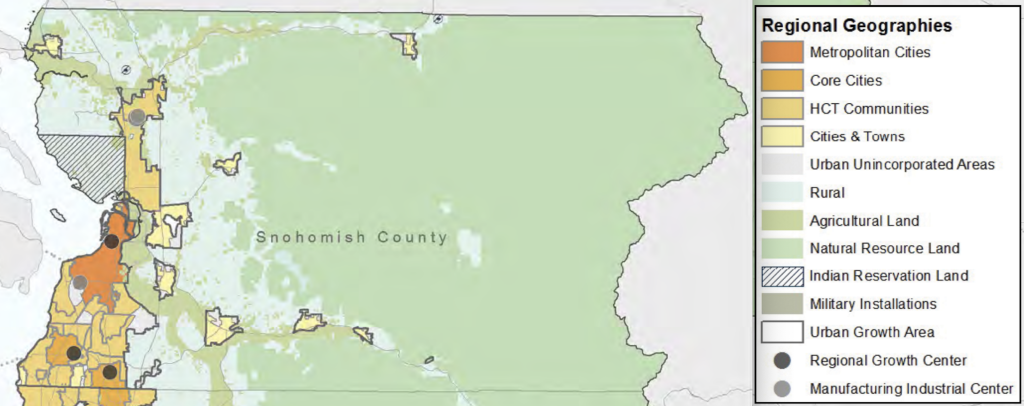

Snohomish County has already started the planning processing for its 2024 comprehensive plan update that will plan for growth over a 20-year time horizon to 2044. A first phase wrapped up with the initial environmental review scoping process the other week, but will need to align with adopted growth targets, at minimum, to be consistent with state, regional, and county planning requirements. A part of the Regional Growth Strategy (VISION 2050), an adopted plan will also need to be consistent with other regional policies by putting most population and job growth in designated Regional Growth Centers, Manufacturing Industrial Centers, and areas served by the high-capacity transit. Designated regional geographies like Metropolitan Cities and Core Cities will also be especially important areas for growth even outside of designated centers.

As part of this, the Snohomish County Tomorrow (SCT) — Snohomish County’s regional planning body — steering committee adopted growth target allocations on Wednesday, December 1st. That clears the way for local governments to use those targets as a basis for developing their updated comprehensive plans.

The adopted growth allocations call for local municipalities to plan for:

- An additional 225,337 residents and 121,263 jobs in the Southwest Urban Growth Area (e.g., Everett, Mill Creek, Lynnwood, and Bothell);

- An additional 72,953 residents and 46,128 jobs in other county urban growth areas (e.g., Stanwood, Marysville, Index, and Monroe); and

- An additional 10,063 residents and 4,427 jobs outside county urban growth areas.

As should be evident, the Southwest Urban Growth Area will have the highest burden to accommodate more residents and jobs. That makes sense given its geographic size, proximity to King County and Seattle, and access to services and amenities (e.g., transportation, schools and colleges, ports, and parks). Cities will take the largest share of growth with an additional 141,067 residents and 106,951 jobs targeted. Chief among these are Everett (68,547 residents and 67,340 jobs), Lynnwood (25,167 residents and 21,912 jobs), and Montlake Terrace, Edmonds, and Bothell each taking about an additional 13,000 residents. In addition, the unincorporated urban growth areas between Lynnwood, Edmonds, Mill Creek, Everett, and Mukilteo are slated to accommodate at least an additional 84,270 residents and 14,312 jobs.

Snotrac raises concerns about application of 65/75 Policy

In advance of the SCT meeting, Snohomish County Transportation Coalition (Snotrac) sent in a letter raising concerns about the growth target allocations. The coalition is especially concerned about whether or not the growth target allocations will actually meet the Regional Growth Strategy updated last year by the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC). The strategy calls for 65% of residential growth and 75% of employment growth to occur in designated Regional Growth Centers and high-capacity transit station areas, which is loosely known as the “65/75 Policy,” throughout the region. King County — one of four counties in the PSRC — will certainly overshoot this number, but other counties may come up short, but whether or not Snohomish County’s targets will help achieve this regional goal is unclear, Snotrac argued.

According to analysis that Snotrac conducted, the coalition believes that Snohomish County should be putting 60% to 65% of population growth and 70% to 75% of employment growth into designated Regional Growth Centers and high-capacity transit station areas.

Assuming the higher county growth target numbers, Snohomish County would need to plan for 229,450 additional residents and 135,000 additional jobs in Regional Growth Centers and high-capacity transit station areas, Snotrac noted in their letter. That would place an especially high emphasis on a smaller subset urban regional geographies designated as Metropolitan Cities, Core Cities, and High Capacity Transit Communities that would need to plan for 88.2% of all additional residents and 90.4% of all additional jobs to be located in Regional Growth Centers and high-capacity transit station areas.

In many ways, that should put a fire under the feet of Everett, Lynnwood, and unincorporated Snohomish County to plan for much higher levels of urban growth broadly in centers and around high-capacity transit. But Snotrac noted in their letter that this could be somewhat misguided. “We are concerned that the burden of reaching the targets may be exceptionally high for communities with the highest levels of high-capacity transit,” Snotrac wrote. “This perverse outcome is primarily due to a possible under-allocation of overall population growth to transit-strong communities relative to transit-light communities.” To demonstrate this, Snotrac pointed to Arlington as an example.

“While Arlington is a High Capacity Transit Community, its only station will be the Swift Gold line at Smokey Point. The development opportunities within a quarter-mile of the Smokey Point Transit Center are limited, especially relative to the total geographic size of the city — the Smokey Point High Capacity Transit Community area is approximately 2% of the city’s total geographic area,” Snotrac wrote. “As a result, it’s highly unlikely that Arlington will be able to put 46.4% of its population growth and 61.5% of its employment growth within its High Capacity Transit Community, let alone the higher targets of 77.1% and 86.3%. Cities like Bothell, Edmonds, Everett, Mountlake Terrace, and Lynnwood will be forced to make up the difference in their communities. It would be more reasonable to allocate more growth to the Metropolitan and Core Cities so that they can have a more reasonable balance between growth within and outside of their Regional Growth Centers and High Capacity Transit Community areas.”

Snohomish County argues it’s consistent with 65/75 Policy

Snohomish County contends that the growth targets are consistent with the 65/75 Policy, at least at the regional geography level. “For the regional geographies that contain regional growth centers (RGCs) and high-capacity transit station areas (HCTAs), i.e., Metro City, Core Cities, and HCT Communities, the share of projected population (82%) and employment growth (87%) is identical between the RGS and the SCT recommendation,” the county told The Urbanist. “In addition, the distribution of high-capacity transit stations in Snohomish County was a key factor that was included in the development of SCT’s 2044 initial growth targets. Specifically, the population and employment growth distributions to 2044 by jurisdictions within the regional geographies of Core Cities and High-Capacity Transit Communities took into account the following two data factors when distributing VISION 2050’s regional geography growth: number of light rail stations [and] number of high-capacity transit stations (non-light rail).”

However, the initial growth target allocations alone may not achieve the more granular concerns that Snotrac has raised, which the county seemed to acknowledge. “Note that the more detailed disaggregation of the jurisdiction-level growth targets in the CPPs to RGCs and HCTAs is not something that the Snohomish County CPPs accomplish,” the county said. “Instead, this is a subsequent step that individual Metro, Core, and HCT Community jurisdictions will engage in during the local plan update efforts leading to 2024.” The county pointed to regional policy that dictates local municipalities plan where the growth goes with a preference towards areas served by high-capacity transit.

Ultimately, the county said that an evaluation will need to be conducted after adoption of the 2024 local plan updates to determine the degree of consistency with the regional 65/75 Policy. The county also added that if the Regional Growth Center and high-capacity transit area growth allocations fell short regionally for some reason, that may be something the PSRC would want to address, such as establishing a resolution or realignment process.

Local governments need to think outside the box

Whether or not the allocations will be realized, equity and sustainability in planning remains to be seen and there’s always ways that municipalities can get around achieving allocations on paper. Everett, for example, has been overly fixated on planning for growth in its downtown almost to the exclusion to the rest of the city. While that’s led to many successes for urban residential infill in the city center over the past decade, the pace of growth has been slower than many had hoped and focused in an area that is further away from many working class jobs in the county. The city’s other key focus for growth has been along Evergreen Way and SR-99, but loud, polluted, and unwalkable highways and stroads make it very difficult for projects to pencil when they’re such undesirable spaces to begin with.

Plans need to be realistic to growth needs and local circumstances now. It’s still a long way to the arrival of light rail north of Lynnwood (2037/2041), so assuming that development is going to happen around station areas that are so far off on the horizon needs to be put in check. Instead, there needs to a more immediate focus on planning for growth in this decade and the assets it will bring.

Despite opposition from wealthy residents, cities like Everett need to be working outside a narrow box in the city center and highways. That means planning for neighborhood retail and denser housing growth in established single-family areas that are transit-accessible and have amenities. All neighborhoods in urban growth areas have a part to play in planning for growth, which is what these upcoming local plan updates need to acknowledge to provide jobs and housing opportunities for new residents and future generations. But will cities double down on old paradigms that are dishonest and don’t work well or try something new and more equitable and sustainable?

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.