A short walk through the long history of discriminatory housing ads

It’s interesting to sift through historic print newspaper advertisements and get a glimpse of the city’s history. It’s not always a good history. Questionable phrases pop up associated with names you recognize. Half acre lots in Innis Arden for $1,500. Four bedrooms in Queen Anne for $7,950. Views from homes in Blue Ridge. All of them with “reasonable restrictions.”

Those restrictions were racial covenants and they covered many new developments in the city from the 1920’s through the 1950’s. Research from the University of Washington has shown how many Seattle deeds to a home had language preventing the property’s sale to specific races, religions, or national origins. In some subdivisions, every deed included a restrictive covenant stating: ”No persons of any race other than the White or Caucasian race shall use or occupy any building or any lot except that this covenant shall not prevent occupancy by domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant.” Those covenants are no longer in effect, but their impact can be seen in Seattle’s segregation.

The Seattle Times is the region’s paper of record. That title has some heft. A full page ad in the Sunday Times is expensive because it still gets noticed. Many municipal decisions and court cases require filing an advertisement in the paper for exactly the same reason — notice. Get out word to the broadest group possible. Historically, that was broadcasting some fairly obvious racism to a receptive public. And the paper made money off of it.

View Ridge

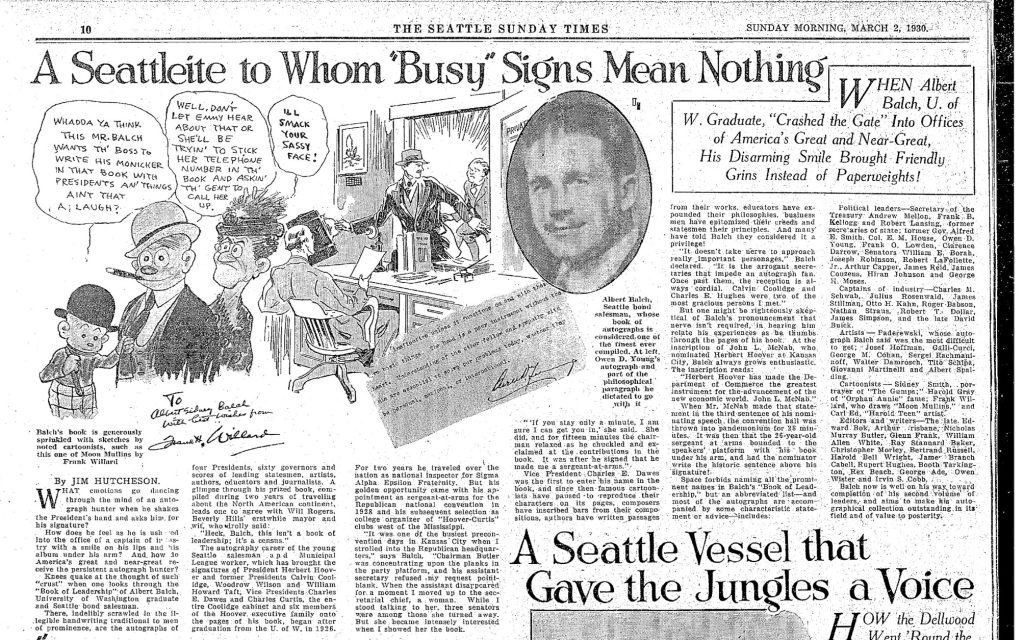

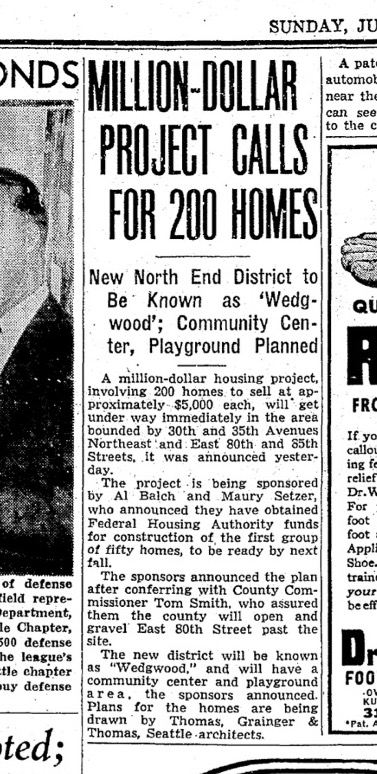

By the time View Ridge was first mentioned in the paper, its developer Albert Balch already graced its pages 50 times. From his UW graduation through a hobby collecting autographs, the social reporters regularly found Balch through the early 1930’s. So when his development project of View Ridge was announced on July 28, 1935, they spelled his name correctly when they identified him as a “non real estate man” who was planning a subdivision. He showed up again on July 6, 1941 when the paper announced Wedgwood under the headline “Million Dollar Project Calls For 200 Homes.”

View Ridge and Wedgwood are in northeast Seattle overlooking Lake Washington and what would become Magnuson Park. With his wife Edith, Balch partnered with the property owner Seattle College to develop the land with racial covenants.

For the next 20 years, a Balch ad appeared almost every day in The Seattle Daily Times. He styled himself a “Community Builder” selling homes with Westinghouse Appliances for Immediate Occupancy. Several ads appeared each Sunday. Many also mentioned the deed covenants, using the phrase “restricted neighborhoods.” During that time, the paper charged 9 to 10 cents per word for a classified ad, depending if it was running during the week or weekend.

Advertisement for Wedgwood Park, a racially restricted development by Albert Balch. This included a “restricted neighborhood” text two years after such covenants were struck down by the Supreme Court. Seattle Daily Times 2/12/1950

Early article about developer Albert Balch, avid collector of autographs. He would go on to develop racially restricted communities of Wedgwood and View Ridge. Seattle Sunday Times 3/2/1930.

Headline announcement of homesites opening in the racially restricted community of Wedgwood. The Seattle Times 7/6/1941

Headline announcement of homesites opening in the racially restricted community of View Ridge. The Seattle Times 7/8/1935

Small newspaper clipping of ongoing development at the racially restricted community of View Ridge. Seattle Daily Times 11/8/1935

“Restricted neighborhood” was language used in classified ads to identify racial covenants in deeds. This is the last identified classified with the language in The Seattle Daily Times 10/24/1971, twenty three years after such covenants were struck down in Shelley v. Kraemer.

Racially restrictive housing covenants were struck down by the US Supreme Court in a 1948 case called Shelley v. Kraemer. There is no record of the paper mentioning the case until 1984. Some Balch ads continued to include the phrase “restricted neighborhood” into the 1950’s. Classified ads in The Seattle Times included the phrase through 1970.

Albert Balch died in 1976. In 2020, the Wedgwood Community Council recognized the role of its deed covenants in segregating the community. The WCC unreservedly apologized, acknowledging “that past actions to ‘protect’ or ‘preserve’ a restricted neighborhood born out of racist covenants, discriminatory lending practices, and exclusionary real estate practices perpetuate the inherently racist systems that shape our community – like so many others.”

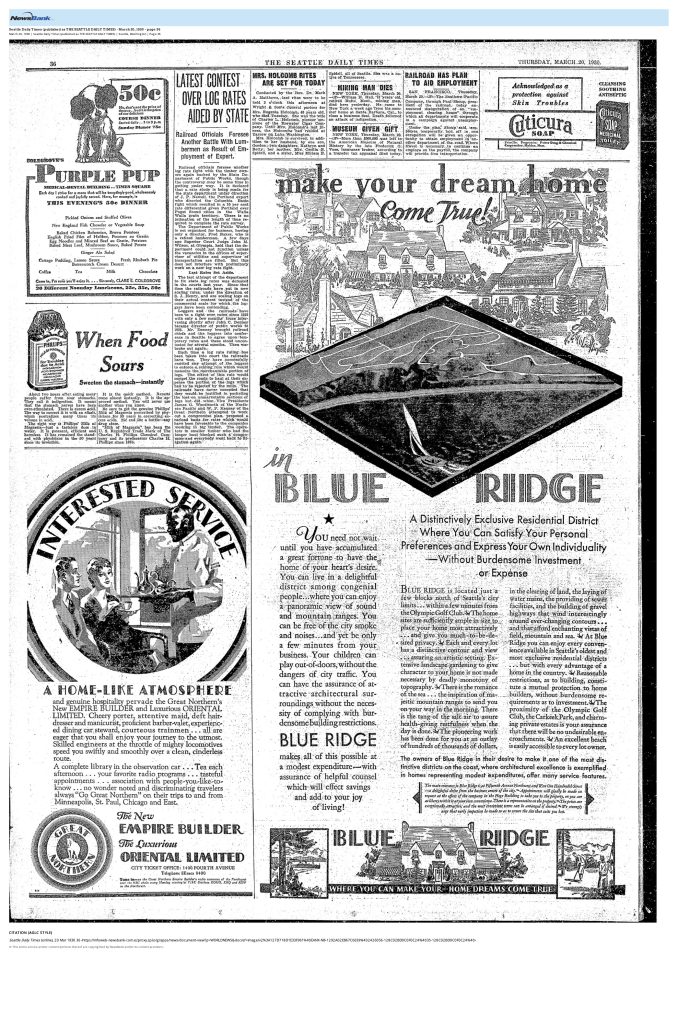

But in that 1930’s and 1940’s era of construction, many other Seattle housing developments got the same splashy announcement treatment, followed by years of ads. On page 11 of the March 20, 1930 edition of the Seattle Daily Times, an article announced “Blue Ridge, New Residence Area, Opens Tomorrow.” The Daily Times was somewhat more loving in describing “stumps, logs, trees and underbrush have given way to four and a half miles of gravel roadways adjoined by residential sites,” than its successor Seattle Times was in describing the expansion of light rail in 2019. The first Blue Ridge ad was on page 36 of the same paper. It touts the proximity to Carkeek Park and Olympic Golf club as “your assurance that there will be no undesirable encroachments.”

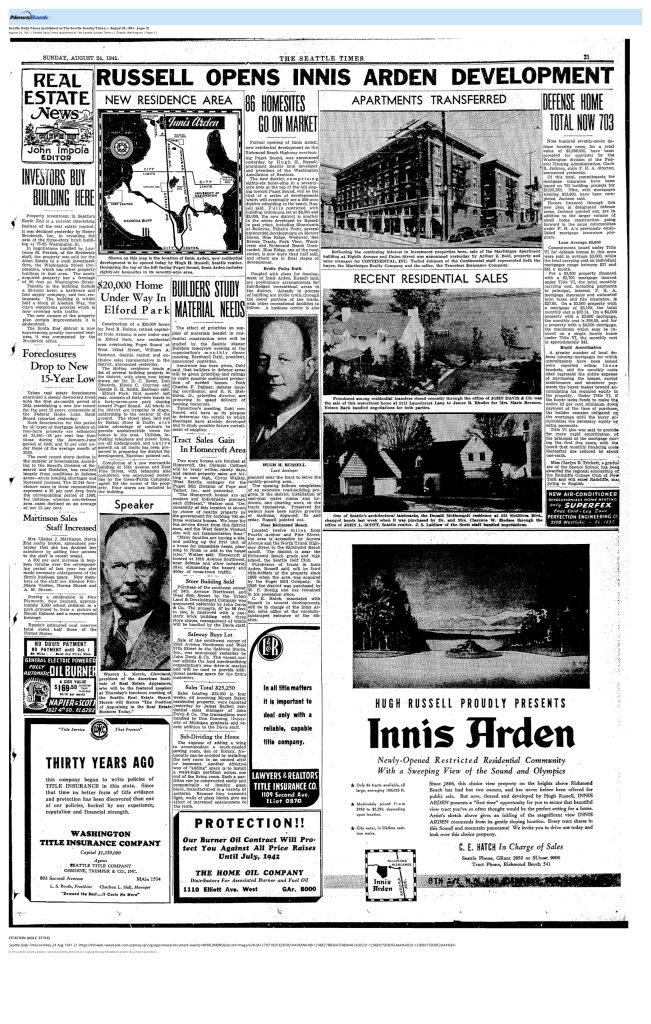

The opening of Innis Arden off Aurora Avenue in northwest Seattle was announced by the paper in an article on September 24, 1941. The second paragraph says “Fully restricted with building minimums set at $4,000 and $5,000.” It was accompanied by an advertisement on the same page. A week later, there was an article and ad combo on the same page with announcements about Wedgwood and View Ridge. By September 21, 1941, regular ads were appearing in the housing section.

Headline announcement of homesites opening in the racially restricted community of Innis Arden. The Seattle Times 8/24/1941

Announcement of tracts sold in the racially restricted community of Innis Arden with accompanying ad from the development. The Seattle Times 8/31/1941

Advertisement for sales in the racially restricted development of Innis Arden. The Seattle Daily Times 9/21/1941

Headline announcement of homesites opening in the racially restricted community of Blue Ridge. The Seattle Daily Times 3/20/1930

Advertisement for the racially restrictive development of Blue Ridge in the same day’s paper. The Seattle Daily Times 3/20/1930.

Links Links Links

Many of these later developments were just following a blueprint set by Broadmoor in the 1920’s. Advertising feeding into the reporting feeding into the advertising. There were two other avenues for ad revenue from Broadmoor: golf and banking.

On October 24, 1924, The Seattle Times carried a quarter page ad announcing Broadmoor Golf Club and Private Residential Park had been surveyed and staked, ready for potential buyers to drive through the community’s new roads. On October 26, 1924, the paper ran the same information as a news item. The article had a little more, such as the 400 applications currently received and that all lighting and telephone wires were buried underground. Put that way, it sounds more like ad copy.

By early 1925, the newspaper was running full page golf News and Gossip section, edited by John H. Dreher and including a cartoon by Briggs. Prior iterations of the weekly feature were called “The Royal and Ancient Game of Golf” and “World’s Links Combed For Followers Of Golf.” In this version, announcements from Broadmoor golf were as constant as the ads for Broadmoor homes in the rest of the paper. The Golf News and Gossip feature ran almost weekly into the 1930’s.

Quarter page ad announcing Broadmoor Golf Club. The Seattle Daily Times 10/24/1924.

Headline announcement of homesites opening in the racially restricted community of Broadmoor, including an ad for the development. The Seattle Daily Times 10/26/1924.

Full page Golf News and Gossip from the Seattle Daily Times, 1/25/1925, including an article about the developing golf course at Broadmoor.

For the record, golf in Seattle would not be racially integrated for decades. Discussions of allowing all races at public clubs were ongoing in the 1940’s. But there were still hurdles to full competition in 1954. That’s when future USGA champion Bill Wright, who was Black, fought local public courses that barred him from playing enough to qualify for professional tournaments. It is unclear when the private Broadmoor club lifted any race-based membership rules. Wright died this year, and there are quite a few good stories about him, including a recounting of hanging up on a Seattle reporter after his first win.

Segregation also funded advertising in The Seattle Times through banks. While developers were writing race restrictive covenants into deeds, banks were denying loans to people of color. This handshake was actually illustrated in a Seattle Times advertisement which listed E. G. Ames as one of the trustees of the Washington Mutual Savings Bank. He was the manager of Puget Mill Company, the owner and developer of Broadmoor.

Advertisement for Washington Mutual Savings Bank listing E.G. Ames, Manager of the Puget Mill Co. and developer of the racially restricted development of Broadmoor as a Trustee. Seattle Daily Times 4/19/1925.

Legal notice of bankruptcy for Washington Mutual, Inc. The Seattle Times 4/17/2020.

In the 1970’s, Washington Mutual Savings Bank was one of the first cited by the Public Reinvestment Review Board, a new Seattle committee enabled by state law to review and prevent the redlining of the previous decades. Washington Mutual Savings Bank was the precursor to Washington Mutual, which collapsed in 2008 before operations were purchased by JPMorgan Chase. As the paper of record, The Seattle Times continues to carry announcements for legal actions, including those for Washington Mutual’s bankruptcy. The paper charges local governments about $2 per line for legal notices.

Finance and golf go together other ways too. Currently, Broadmoor’s golf property is being reviewed for property tax valuation. Notoriously underassessed as unbuildable land, the sites should pay tens of millions of dollars more each year, but don’t through some sleight of hand by the King County Assessor.

Reckonings Today

In this century, Seattle’s local newspaper has provided several opportunities for parts of the housing industry to reckon with their segregationist pasts. Last year, there was coverage of area Realtors struggling with the issue. “The white-dominated real estate industry’s participation in discriminatory practices like redlining, racist covenants and steering, according to academic and journalistic research, has had a hand in creating and perpetuating” a widening racial homeownership gap.

The first time the word “redlining” was used in The Seattle Times was on July 12, 1971. An article from the Times News Services titled “Official Blasts Bank Policies” covered Sherman J. Maisel’s report to the Federal Reserve concerning lenders’ roles in the deterioration of the inner city. The article concludes saying bank’s simplified analysis determining risk and profit lead “lenders to concentrate their loans in new homogeneous suburbs while redlining major sectors of the inner city.”

The article was followed by a short blurb about a Boeing exec’s promotion. That day’s paper had a dozen classified ads selling properties in Innis Arden, Blue Ridge, and Queen Anne. The ads no longer mentioned “reasonable restrictions” though many of those deeds reflect the legacy of segregation fifty years later — an indelible record deeply tied to The Seattle Times.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.