Early next year, the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), the region’s four-county planning agency, will release a draft of the update to its Regional Transportation Plan, which unfortunately does not appear to be a climate-focused document. Updated every four years, the plan outlines shared priorities around transportation, many of which are driven by VISION 2050, the agency’s regional housing and employment growth plan. This update to the Regional Transportation Plan will extend the plan’s timeline from 2040 to 2050 to align with that growth plan, which was adopted in 2020.

Both plans are an attempt to dictate how the region as a whole responds to what is expected to be an increase in population of close to two million people across the central Puget Sound in the next 30 years, over a third of which is expected to be accommodated within the region’s five core cities — Seattle, Tacoma, Bellevue, Everett, and Bremerton. The transportation plan assembles all of the transportation projects that are expected to be completed by all levels of government during those decades and looks at how they serve the region’s overall goals.

The previous version of the regional transportation plan, from 2018, outlined a number of critical transit investments that the region needed to make over the next two decades, but ultimately set its ambitions very low, with the rate of overall trips regionally made by public transit only expected to rise from 3% to 5% in 22 years.

Over the past few months, some details from the draft 2050 plan have been presented by PSRC staff to elected leaders from the region that steward these plans, so we already know a lot about what the plan will look like before it’s officially released for public comment.

Ultimately, the overall plan for transportation is for everyone to drive a little less, on average, but for everyone as a whole to drive a lot more. By 2050, the projection is that the average household in the region will drive 12,300 miles per year, a 23% reduction compared to 2018. Those miles will be offset by an increase in the average resident’s time taking transit and walking or rolling for transportation. Transit boardings across the region are expected to triple by midcentury, and the average central Puget Sound resident is forecast to spend 35 minutes per day getting around via active transportation, up from 29 minutes in 2018.

Those reductions aren’t enough to keep vehicle miles travelled (VMT) from the total number of passenger vehicles on the region’s roads from increasing by approximately 15% by 2050. To accommodate those extra trips, the region would invest in expanded road capacity in addition to expanding light rail, bus rapid transit, passenger ferries, and walking and biking trails. An associated project list includes $12.1 billion in road expansion projects that would add general purpose lane capacity, $10 billion to expanded interchanges to accommodate additional general purpose traffic, and $8.3 billion in brand new roads.

Planners guiding the update looked at traffic congestion regionally as of 2018 and determined that 21% of the region’s roadways were considered congested. After that significant planned expenditure on road capacity, which is completely separate from maintaining and preserving the current street and highway network, regional planners now expect 25% of the region’s roadways to be congested in 2050, which is somehow considered a success when graded against the large increases in population. But a major outcome of this is that users of the road system without alternatives, including heavy haul truck drivers and residents of unincorporated areas of the region that lack transit access, are forecast to individually spend more time sitting in traffic in 2050, as part of our plan. A heavy truck driver spending 56 hours every year sitting in traffic is expected to spend 74 hours in traffic in 2050, really illustrating the urgent need for dedicated freight lanes to take priority over generic road expansion.

Meanwhile, the plan assumes that the average households in the region’s five core cities will still put 22 miles on their vehicles’ odometers every single day in 2050, and that households in cities that are explicitly named in PSRC’s growth strategy as “High Capacity Transit Communities” (like Edmonds, Mercer Island, Port Orchard and Bainbridge Island) will be driving over 45 miles per day.

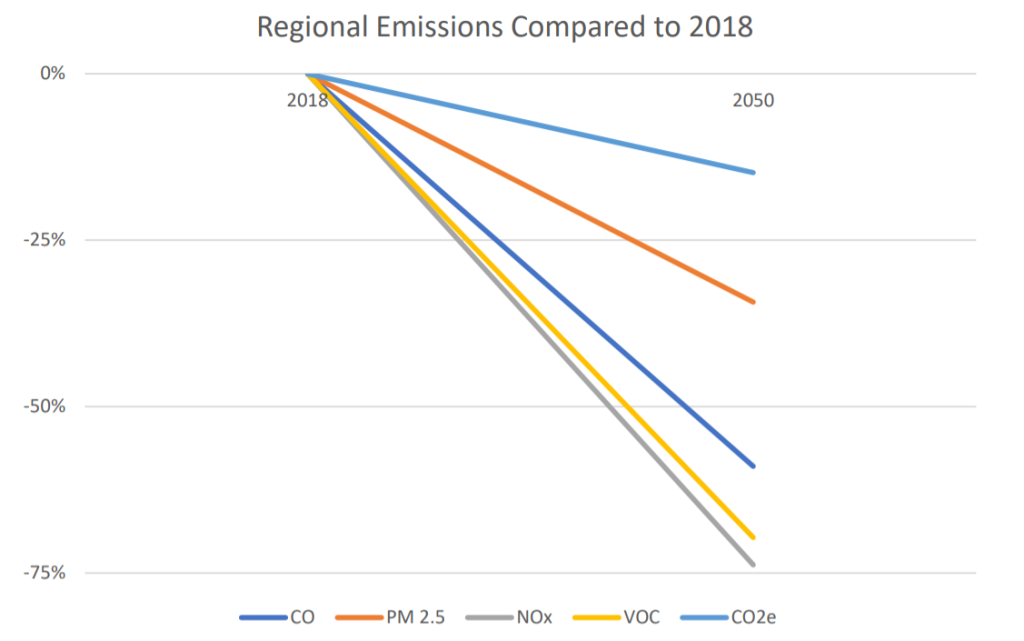

A major yardstick that the plan will be judged against is the degree to which it is forecast to guide a reduction in emissions. Passenger vehicles are the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the region, so a plan for transportation in the state’s largest region would be by necessity directly related to the state’s climate goals. By 2050, Washington’s emissions are currently pledged to be reduced to 95% of their 1990 levels.

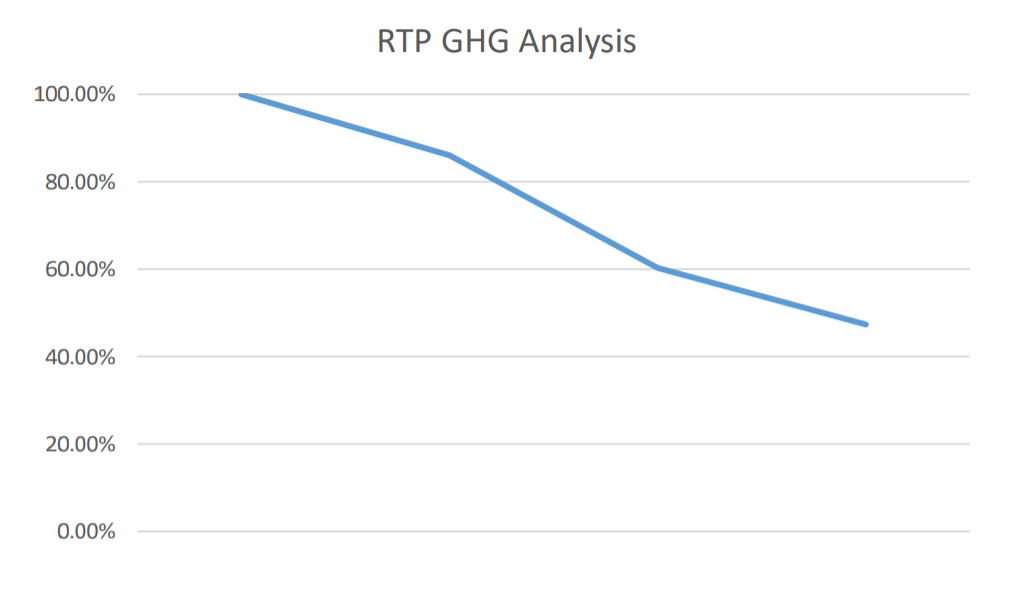

At a meeting of the Transportation Policy Board meeting in September, board members were shown a chart illustrating a change in CO2 equivalents (GHGs) from 2018 levels in 2050 that was only around 15%.

PSRC’s Director of Transportation Planning, Kelly McGourty, described the model that produced this result as the agency’s “standard” one. That result was produced before applying what is referred to as the “Four Part Greenhouse Gas Strategy,” which includes an analysis of land use, user fees (tolls and a possible per-mile user fee), and technology in addition to the choices available to users of the transportation system. What’s notable is that this strategy doesn’t assume any changes in the transportation projects prioritized for funding, with many of those policy outcomes—particularly the speed of the transition of the vehicle fleet to low-emission—outside the control of PSRC.

But even when that four-part strategy was applied to the plan only showed a 50% reduction in greenhouse gases.

PSRC’s current President, King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci, raised the issue at an October meeting, noting that PSRC had signed onto a goal to get to 95% by 2050, and asking for at least one version of the plan to be considered that could achieve those reductions. “I do think we need to have in front of us an option that shows us what it would look like to meet our climate goals, and we can decide we’re not ready for that and figure out how we get there some other way, but I think we have to, with a straight face, look ourselves in the Zoom box and say ‘this is what it’s going to really take’.”

At that same meeting, Burien Councilmember Nancy Tosta echoed Balducci’s comments. “PSRC has to provide the leadership that contributes to us being able to accomplish some of these climate action goals that we’re laying out in our local jurisdictions,” she said.

Kelly McGourty responded to Balducci’s comments by saying that the analysis on GHGs was in an “early” stage and that the agency would be looking at what would need to be done to match the climate goals. In an email, she told me that a “fairly conservative approach” was taken in the analysis that led to the 50% number, including a projection that 35-60% of the passenger vehicle fleet regionally would be zero-emission by 2050.

McGourty said that a road usage charge, currently headed toward pilot stage in Washington, is assumed for the second half of the plan’s horizon, with a 5-cent off-peak and a 10-cent peak-period fee per mile used in the analysis. Of course, those user fees do have an effect on demand for roadways and therefore the resulting number of collective miles travelled, but it’s not clear the degree to which the region’s roadway expansion projects will be reassessed using demand management in that way.

This isn’t the first time that PSRC’s plan for regional transportation has fallen short even just in its ambitions for emissions reduction in comparison with our state and regional climate goals. In 2010, when the agency released that year’s version of the plan that extended to 2040, Cascade Bicycle Club, Futurewise, and the Sierra Club filed a lawsuit after the plan was adopted. That suit contended that PSRC was required to adopt a plan that reduced emissions to a level that matches the statewide targets, which at that time were “merely” a 50% reduction compared to 1990 levels by 2050.

That lawsuit failed, with a court of appeals affirming that PSRC was not actually a signatory to the climate goals that were adopted by the legislature, and noting that different levels of government aren’t expected to reduce emissions by an amount that is exactly equal to what the state goals call for. Since that time, emissions from transportation have continued to go up regionally. Now deeper emissions reductions are required, and we’re right back in the same place with a regional transportation plan that appears out-of-sync with the reductions everyone agrees are required.

Next month, we will know a lot more about the intricacies of the plan as the full draft plan is released to the public for comment, but it’s clear that climate advocates will have to push the regional leaders who guide PSRC to make sure that the plan that is ultimately adopted aligns with the region’s values around climate.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.