Some motorists think they should be above the law

Automatic traffic cameras are being installed in eight Seattle locations and three state legislators are “crying foul” and fretting over expected impacts to their constituents. Senator Kevin Van De Wege (D-Sequim) posted a press release on his webpage stating the trio of lawmakers is “uneasy that their constituents and other visitors to Seattle might unknowingly be recorded on camera violating a new law unlike any traffic laws outside the city limits.”

In fact, it’s illegal to block a crosswalk or intersection, or drive in transit lanes by state law. However, it may be true that Seattle is one of the few jurisdictions actively working to enforce these traffic laws. And for this, the trio of lawmakers — who voted against the bill authorizing pilot program of automatic camera enforcement back in Spring 2020 — think they should get extra warning and dispensation. Already the law comes with a warning for the first infraction; after the warning, subsequent infractions come with a relatively modest $75.

“Seattle has every right to enforce its traffic laws, but people need fair warning,” said press release co-signatory Senator Lisa Wellman (D-Mercer Island) in a statement. “You can’t just approve a law that doesn’t exist in any other community in the state and expect people to magically know that the rules are very different when they drive into Seattle.”

The dissenting lawmakers acknowledge Seattle’s education and signage efforts before dismissing their effectiveness. Representative Mike Chapman (D-Port Angeles) also signed on to the press release and seemed to argue blocking crosswalks is par for the course on the Olympic Peninsula and that being expected to read signs was too much to ask.

“When I’m driving, and I don’t think I’m that different from a lot of my constituents, I’m watching the road and other cars,” Chapman said in a statement. “I’m not looking at signs unless I’m searching for a particular street sign to make a turn. My constituents are good, law-abiding people, but it’s hard to obey a law you’ve never heard about. Traffic laws are typically uniform from community to community, but this isn’t a law anywhere else in the state.”

While traffic signs are indecipherable, traffic congestion apparently is a foreign concept outside of Seattle.

“You see traffic in Seattle that you just don’t see in our rural 24th District,” Van De Wege said in a statement. “Traffic doesn’t suddenly stop dead at intersections in our communities the way it can in Seattle.”

Shockingly, rather than seeking to educate their constituents about a new program aimed at improving street safety and transit operations in Seattle, the trio of lawmakers seemed to argue people in their districts are hopeless cases beyond educating — a take based on their mistaken belief that blocking crosswalks, intersections, and transit lanes is perfectly legal in their communities.

“The lawmakers say there is no way to adequately publicize an uncommon, Seattle-specific law to infrequent visitors from other cities, towns or rural areas,” their release states.

As advocate Rachael Ludwick quipped, “There is a solution to this law being special to Seattle: allow every locality in the state to do this and provide funding for it. Problem solved.” Rather than governing to the lowest common denominator, we could be raising standards across the state to improve conditions for people walking, rolling, biking, and riding transit. Unfortunately, that’s not the course taken by Van De Wege, Wellman, and Chapman.

The final sentence of the press release hints at what they are really on about: “All three legislators voted against the bill when it passed the Senate and House in 2020.” Van De Wege and Wellman were the only two Democratic Senators to oppose the bill.

The bill provided authorization for Seattle’s camera enforcement pilot program through June 30, 2023 and limits the scope to 20 intersections in the core of Seattle. Though administered by the City of Seattle, the program provides a revenue stream for the state — a concession likely added to help get the votes. After accounting for expenses, fine revenue will be split equally between the City of Seattle and the Washington Traffic Safety Commission.

“Seattle’s portion is planned to be dedicated to adding Accessible Pedestrian Signals to intersections around the city,” Ryan Packer noted in their reporting. “The Traffic Safety Commission’s expenditures tend to be more focused around the areas of education and enforcement. A recent update on the Spokane Street cameras detailed that both shares were approximately $390,000 for the period of January through July, with an overhead cost of 24.8% over that timeframe.”

Seattle could have started issuing warnings in 2020 and charging fines in January 2021, but the Durkan administration has been slow to roll out the program, which it blamed on the pandemic. The only place automatic camera enforcement is in place so far is the Spokane Street low bridge to West Seattle, which is transit and freight only during peak hours following the West Seattle High-rise Bridge closure, but will likely revert to general purpose traffic once the high bridge reopens in mid 2022.

Disability rights advocates led crosswalk camera charge

The legislation authorizing crosswalk and bus lane cameras came at the behest of safety and transit advocates, including groups like Disability Rights Washington (DRW), Transportation Choices Coalition (TCC), and The Urbanist. “Safer streets and more reliable transit are on the way,” TCC said upon the bill’s passage.

DRW’s video-focused offshoot Rooted in Rights made a video that popularized the issue by showing the plight of disabled wheelchair users seeking to cross Mercer Street as crosswalks and intersections were inundated with cars during rush hour.

“Everyone should be able to access our streets and sidewalks, especially those of us who rely on walking, rolling and buses to get where we need to go,” said Anna Zivarts, who was Rooted in Right’s Program Director at the time. “Thanks to everyone in the legislature who stood up for the disability community and their transit-dependent constituents!”

The dissenting press release makes no mention of the impact creating a giant ‘oops I’m not from Seattle’ carveout in traffic laws would have on disabled community who fought so hard for these protections. They also fail to mention how popular transit lanes, pedestrian improvements, and street calming is in Seattle, as recent polling confirmed. Why these improvements should be held hostages to visitors who refuse to even bother to try learn the law remains a mystery.

Pedestrian deaths have been on an upward trend and spiked even more this year. The failure to design safe streets and hold motorists accountable for their behavior are primary culprits.

Expanding the camera program

Seattle will need to seek an extension of state authorization by 2023 to avoid a lapse in automatic enforcement. It appears Van De Wege, Wellman, and Chapman will continue to be tough sells based on their ongoing hostility to the program. But perhaps the votes are still there outside those holdouts.

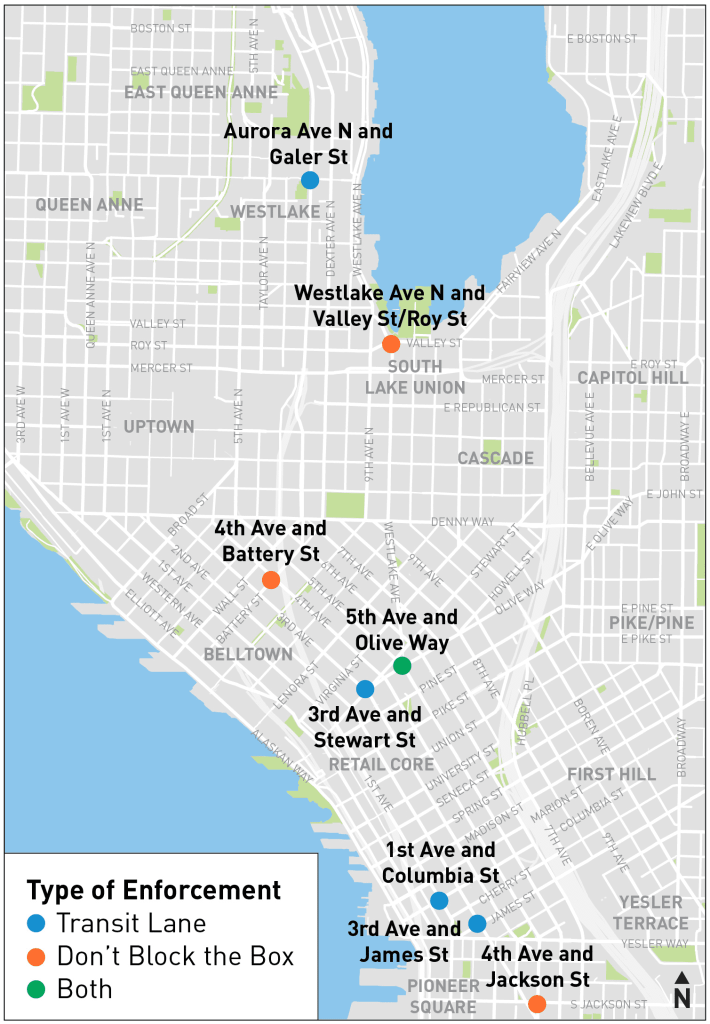

After being more than a year late in implementing the program, Seattle has about 18 months to demonstrate the program’s success. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) can add 12 more intersections to the program.

The City has yet to add any enforcement cameras on Mercer Street despite it being the posterchild for crosswalk blocking. A SDOT spokesperson told The Urbanist‘s Ryan Packer that Mercer was not selected in the first round because traffic lights on the street are not readily compatible with the automatic cameras. Installing cameras on Mercer will take adding new poles, apparently. Since Mercer Street continues to have a huge blocking problem, the City would be wise to find a way to get it done.

Third Avenue, meanwhile, is slotted to have just one traffic camera despite being the city busiest transit artery. If the first traffic camera at 3rd Avenue and Stewart Avenue proves insufficient, SDOT should certainly add more and consider extending 3rd Avenue bus only restrictions through Belltown to Denny Way. Traffic cameras could also offer a way to keep transit moving before and after events at the newly opened Climate Pledge Arena, a facility to which driving and ridehailing is expected to compose about 80% of trips and transit just 8%, with SDOT hoping to double that as soon as possible and triple it by 2035.

The City of Seattle is aiming to eliminate traffic deaths and achieve carbon neutrality by 2030. If the city can’t enforce transit lanes and crosswalks, those goals will certainly be out of reach on any timeline.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.