As a child, I watched a documentary at school about Arcosanti, a utopian city in the desert founded on the idea that environmental sustainability and community life should be the top priorities in a city’s design. While Arcosanti made a big impression on me at the time, to call it a city is misleading because this “living urban laboratory,” which was mapped out by creator Paolo Solteri to accommodate 5,000 residents, has only grown to about 70 full-time inhabitants since its groundbreaking in 1978.

Now billionaire and former Walmart executive Mark Lore has dreamt up plans for building another utopian city in the desert, Telosa, whose mission Lore says in its launch video is to become “the most open, the most fair, and the most inclusive city in the world.”

Despite its tiny size, tens of thousands of visitors flock to Arcosanti each year to observe and participate in the workings of the unique site, which promotes itself as a “living urban laboratory.” Yet, well intentioned as it is, Arcosanti, whose name is a play on the words “arc,” “cosa” (thing in Italian), and “anti,” has never evolved beyond a novelty attraction.

Telosa, whose name derives from the ancient Greek word “telos” meaning “highest purpose,” has borrowed a lot from Arcosanti in how it aspires to prioritize environmental sustainability and equitable community development. Going further, just as Arcosanti revealed cracks in the hyper-consumerism of the post World War II era, Lore’s plans for Telosa, which he says will be founded on the principles of “equitism,” his own self-styled vision of a combination capitalism and equity, reveal a lot about contemporary America’s social and economic ills.

Learn more about Telosa here: https://t.co/w5fDQVOCS0 pic.twitter.com/6al6g9cNBT

— City of Telosa (@CityofTelosa) September 1, 2021

It’s easy to dismiss utopias like Telosa, especially since aspects of the project make it feel more like a billionaire’s vanity scheme than an earnest attempt to address the very real problems related to equity and sustainability plaguing cities in the United States, and the world, today.

But there are also lessons to take away from the city and the vein of thought that supports its vision. Utopias can serve as foils to the our real world cities, drawing into contrast their weaknesses and strengths, while also mounting ideas for improvement. So while maintaining a healthy dose of skepticism, let’s take a closer look at Lore’s plans for Telosa.

Telosa’s goal: 50,000 residents by 2030

Telosa is currently in its earliest stages. Although its website states Telosa will be ready for people to begin moving in by 2030, the location remains to be determined. Planners are currently scouting “cheap land” in Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Arizona, and Texas. Also under consideration is the Appalachia region of the eastern U.S., although this possibility seems the least likely.

Building Telosa on inexpensive, uninhabited land is important because of Lore’s unique economic plan for the city. Lore envisions that the future city’s land will be purchased by investors and philanthropists and then donated to a community endowment, which will use increases in the land’s value to fund public services such as healthcare, education, and small business development. While the land will be owned by the community endowment, people will be able to build, buy, and sell their own homes.

Lore was inspired to pursue building a city in this model after reading the 19th century book Progress and Poverty by Henry George, which promotes the idea that capturing the value of land ownership for the good of the community can help avoid capitalism’s boom and bust cycles, while also decreasing unfair wealth concentration. During the 1890s, Progress and Poverty was the most widely read book in the United States after the Bible, and it had made a huge imprint on progressive social movements around the world in the early 20th century.

To illustrate what his conception of equitism could look like practice, Lore gives the example of Manhattan. According to his estimates, if all the land in Manhattan was owned by a community endowment, it would be worth over $1 trillion and generate over $60 billion in annual revenue — money that could be invested in both the city’s built environment and its people. Lore says that would more than double the current annual spending in Manhattan on its infrastructure and social programs, which aligns with figures provided by City of New York’s budget office, which show spending among all five boroughs has hovered over $90 billion in recent years.

Currently, cities rely on a complex system of taxes, levies, and fees to finance these kinds of investments. Lore believes that using a community endowment will be more equitable while also raising more funding than conventional means do. For examples of where this funding mechanism has already been used, he points to “Alaska, Utah, nearly twenty cities throughout Pennsylvania, and leading universities, such as Stanford.”

Because of the centrality of equitism to Telosa’s design, Lore believes his project should not be viewed in the same lens as other planned cities currently in the works, for example Neom in Saudi Arabia, which is being designed as a futuristic desert oasis, and the first of a 106-mile-long belt of hyperconnected communities spanning across the kingdom.

“Cities to date that have been built from scratch are more like real estate projects. They don’t start with people at the center because if you start with people at the center you immediately begin to think, okay, what’s the mission and what are the values?” Lore said.

Lore has enlisted renowned Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, best known for the innovative Copenhill waste-to-energy plant ski slope, to mastermind designs for the city. “Telosa in my mind embodies the social and environmental care of a kind of Scandinavian culture, and the freedom and opportunity of a more American culture,” Ingels said in the launch video.

Ingels and his team will be working as part of the Junto Group, which has been formed to guide all areas of Telosa’s development. On the city’s website, the Junto Group is described as “a diverse team of urban planners, designers, historians, community engagement experts, economists, financial managers, scientists, and engineers… who are committed to working collaboratively across different ideologies, backgrounds, and perspectives to create a new city that is sustainable and equitable to all.”

Phase one of Telosa’s development is projected to cost $25 billion, and will be funded primarily by investors and philanthropists, although government grants and subsidies may cover some costs as well. The total cost of building Telosa is estimated to surpass $400 billion, according to the city’s website. Lore, whose current net worth is estimated at $500 billion, plans to pay for some of the costs out of his own pocket by using returns on his startup investments.

Some of the greatest expenses in Telosa will be related to the city’s environmental challenges. Building on cheap land in the desert comes with disadvantages, most notably lack of water – which incidentally is already a major challenge for U.S. cities like Los Angeles, Miami, Phoenix, and Atlanta. Critics have noted that the climate crisis will only worsen water shortages.

“I love that [Lore] is trying to reframe but not break the mold,” said Ellen Dunham-Jones, an urban design professor at Georgia Tech University in an article for Fortune Magazine. “But the idea of supporting a million people on worthless land is a tough hill to climb.”

Telosa’s website touts the city’s environmental plans, which include a sophisticated system that could “store, clean, and reuse fresh water” on site, as well as an energy system powered by renewables. By starting with a “clean architectural slate,” Telosa’s designers will aim to design for density and urban street system focused on pedestrians and cyclists, although plans for autonomous vehicles in the form of shuttles, as well as other forms of mass transit, are also prominent in designs that have been released to the public.

Specific plans for the design of the city remain vague beyond the evocative rendering; however, the website does promote the future Equitism tower as the city’s centerpiece. Set in Telosa’s central park, the tower is forecast to have a photovoltaic roof, elevated water storage, and aeroponic farms, which “enable the structure to share and distribute all it produces.”

Who will live in this future utopian city? Lore has suggested that the first 50,000 residents will be selected using an application process that will be focused on “diversity and inclusion.” In order to help draw initial residents and kickstart the local economy, a venture capital fund controlled by Lore would make investments in startups that relocate to the city.

While Lore and his team plan to select the initial residents, he has pledged that the future city will be governed by “transparent participatory democracy” land led by a council and city manager.

What can we learn from Telosa?

You are not alone if you are less than impressed by the idea of building a brand new city on low value land in middle of uninhabited desert while a global climate crisis breathes down our necks. In the short time since its launch, Telosa has amassed its share of critics. And yet, there are some valuable takeaways to be made from Telosa, probably the most compelling of which is Lore’s vision of radically expanding shared ownership of land.

Community land trusts, have already been proven to an effective way to create affordable housing and build wealth among society members who have been historically been excluded. In a community land trust model, land is acquired by a trust that maintains permanent ownership. Housing developed on the land is leased by homeowners, who agree to earn only a portion of the increased property value during future sales. The remainder is invested back into the trust, preserving affordability for future low- to moderate-income families.

According to the Democracy Collaborative, there are currently 277 community land trusts in the United States. Residents of community land trusts tend to have a different profile than the typical American homebuyer — 79% of residents are first-time home buyers, 82% earn half or less of their local area median income (AMI), and 31% identify as people of color.

Massively expanding access to community land trusts, especially in rapidly growing metros like Seattle, would increase opportunities for stable housing and provide a counter balance to market forces that tip the scales away from housing affordability. In Vienna, where roughly 25% of the city’s housing stock is owned by the local government as a result of a unique system of public-private partnership with limited profit developers, the city has been able to maintain housing affordability and choices even as the city has risen to top of international indexes ranking quality of life. In all, 60% of Vienna’s housing stock is social housing outside of the private market, while Seattle is roughly 8% social housing.

Instead of acquiring land to build a city from scratch, Lore and other affluent philanthropically inclined investors could help community land trusts across the U.S. buy land and finance new housing developments, particularly in the areas of the country that would benefit the most, like Detroit where surging housing prices and a relatively low wage economy has made it difficult for residents to make ends meet.

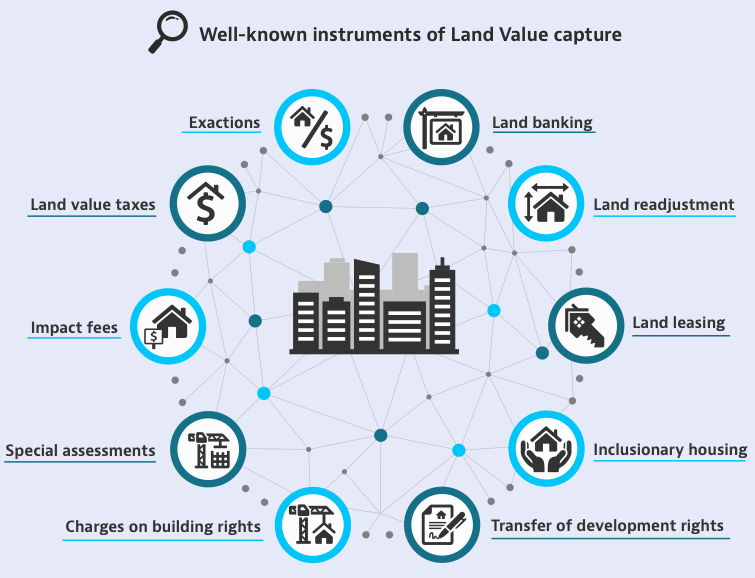

In addition to expanding shared land ownership opportunities, cities can find inspiration in Telosa’s concept of using a community endowment to help fund city infrastructure and services. In a growing city like Seattle, local government could also harness growing land prices for the benefit of the community by using a suite of tools known as land value capture.

In his article for The Urbanist, Ron Davis argued that selling development rights, a common land value capture tool, the City of Seattle could potentially earn hundreds of millions of dollars each year that could be invested in affordable housing, public transit, and human services. Additionally, through inclusionary zoning included in its Mandatory Housing Affordability program (MHA), Seattle already raised $52.3 million for affordable housing in 2020 alone.

Finally, while Lore has emphasized how building Telosa from a blank slate will enable the creation of superior transportation designed around walking, biking, and transit, lessons learned during the Covid pandemic show that with bold policy changes and investments cities can reconfigure their existing transportation systems so to prioritize people instead of vehicles. While the best examples of these changes can be found in European metropoles like Paris and Barcelona, which admittedly already had walkable streetscapes and transit rich planning, even some more car-centric North American systems like Montréal, which added 327 kilometers of bike and pedestrian paths during the pandemic show it is possible. Seattle’s investment in Link light rail expansion, which will be adding 34 miles of new light rail (with 25 stations) by 2024, also demonstrates it is possible to make transformative progress in expanding quality public transit.

A city doesn’t have to be built from the ground up to harness some of the good ideas Telosa seeks to embody, and it’s possible that it will be these city building ideas that may prove to be Telosa’s greatest legacy. Rather than invest millions — or billions — of dollars into what will likely be another utopian museum piece like Arcosanti, Lore would be better served to use his fortune to scale up his vision of community owned land, increased levels of investment in the public good, and dense, walkable, and transit-rich built environments in cities that already exist.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.