Homelessness was the dominant campaign issue, but housing looms as an issue progressives can win on.

On election night, Lorena González was down 29.6 points in the Seattle Mayor’s race, City Attorney candidate Nicole Thomas-Kennedy was down 17.3 points, City Council candidate Nikkita Oliver was down 20.8 points, and incumbent Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda was up only 5.3 points on Kenneth Wilson, a relative unknown who raised little money and garnered few endorsements.

Only half of the expected turnout had been counted and veterans of covering Seattle elections warned the final results would look quite a bit different. Still, many pundits indulged in hot takes gloating how badly progressives had failed — and in some ways they did (as I wrote about last Friday). Ultimately, none of those candidates made a miraculous comeback, but the margins did tighten considerably, which muddies the clean narrative of progressive repudiation some had advanced.

With virtually all the ballots counted now, González is down 17.5 points, Thomas-Kennedy is down 3.8 points, City Council candidate Nikkita Oliver is down 7.9 points, and Mosqueda is up 19.2 points. Thus, from election night, González gained 12 points, Thomas-Kennedy and Oliver gained 13 points, and Mosqueda gained almost 14 points.

- González: -29.6 –> -17.5 = +12.1 point swing

- Oliver: -20.8 –> -7.9 = +12.9 point swing

- Thomas-Kennedy: -17.3 –> -3.8 = +13.5 point swing

- Mosqueda: +5.3 –> +19.2 = +13.9 point swing

A 13 point progressive swing from election night to the final result is starting to be routine in Seattle, with Councilmember Kshama Sawant and Shaun Scott also matching the feat in 2019. That swing propelled Sawant to victory, but Scott came up four points short.

A 19-point win for Councilmember Mosqueda is hard to rectify with a 17-point loss for Council President González. Perhaps, Wilson was really that weak of an opponent. The centrist political machine never really adopted him and funneled money and endorsements his way like they did for Mayor-Elect Bruce Harrell, Councilmember-Elect Sara Nelson, and newly elected Republican City Attorney Ann Davison. Voters appear frustrated with the City Council and a perceived lack of progress on key issues, but they’re also leery of electing novices like Wilson.

A well-worn approach to homelessness

Harrell, a former three-term Councilmember himself, seemed to convince voters he represented a new approach while running on policies very similar to Mayor Jenny Durkan and with the support of 12 former or current Seattle City Councilmembers and five former Seattle Mayors. But, between his platform and the cadre of endorsements he received, Harrell seems to represent a return to the old approach that attempted to solve homelessness with technocratic fixes, task forces, encampment removals, and whatever new fad came along so long as it wasn’t a major new revenue stream to fund permanent affordable housing and wrap around services on the scale needed.

Seattle declared war on homelessness under Mayors Norm Rice and Greg Nickels, who both endorsed Harrell. The pair of two-term mayors ran Seattle from 1998 through 2012, with four years of Paul Schell in the middle. Nickels declared a 10-year plan to end homelessness, but failed to make a dent and came up short in his quest to establish a regional partnership to mobilize the suburbs behind homelessness solutions. In 2015, Mayor Ed Murray went so far as to declare a state of emergency around homelessness along with County Executive Constantine. Homelessness continued to rise under Mayor Murray’s tenure.

In 2017, Durkan ran a campaign that attempted to paint her opponent Cary Moon into a corner for expressing interest in a right-to-shelter ordinance, which Durkan opposed due to cost concerns. Durkan alleged ensuring shelter for all would divert resources from permanent affordable housing and released a homelessness plan that promised 1,000 new tiny homes in her first year and a rent voucher program supplementing low-income tenants by a few hundred dollars per month. Durkan won the election handily, but she implemented neither program; she completed just 73 tiny homes in her first year.

Four years later, Harrell ran on building emergency shelter for 2,000 homeless people as soon as possible so that he could clear parks of encampments. Suddenly shifting focus from permanent housing to temporary emergency shelter was greeted as visionary in establishment circles whereas four years ago it had been naïve and a distracting from real solutions.

Centrist politicians flit from one idea to another, but meanwhile numerous studies sit on the shelf have found that Seattle should spend much more money on supportive housing and homelessness services in order to end homelessness — something on the order of one billion per year according to a 2020 McKinsey report.

Failure to connect homelessness to restrictive housing policies

Returning to the 1990s, Mayor Rice, for his part, implemented the urban village strategy that cordoned the vast majority of housing growth into a handful of urban centers and hubs, plus some business districts, which in all represented about 12% of the city’s land, while reserving roughly 30 square miles exclusively for single family homes. Most single family zoned neighborhoods saw effectively zero growth — and in many cases even a negative population growth rate. Meanwhile, population in urban villages and centers shot up dramatically. And with so little land dedicated to apartments and townhomes, prices for that land and housing on top of them skyrocketed, as well. In King County, rents jumped 52% from 2010 to 2017.

More than anything else, the rapidly rising price of housing seems to be driving factor in the rise of homelessness, but no mayor has attempted to shift the fundamental land use imbalance dating back to Mayor Rice’s urban village strategy in 1994. The City now has in its hands a racial equity analysis of the urban village strategy telling them that reform is needed, but that’s not the campaign pledge that Harrell ran on.

On the campaign trail, Harrell ripped into González for proposing to “abolish” single family zoning in favor of base zoning that allows triplexes, fourplexes, and perhaps some small apartment buildings. González’s approach would have followed in the footsteps of cities like Portland, Minneapolis, Sacramento, Berkeley, and even Grand Rapids, Michigan, but Harrell painted it as radical and out of step. In doing so, Harrell mirrored Trump’s desperate attacks arguing Joe Biden wanted to abolish the suburbs. However, with issues of homelessness and policing dominating the election, Harrell paid little price for his reactionary approach on housing policy.

Even Norm Rice admitted the urban village strategy is due for an overhaul in a Crosscut article from David Kroman looking at what the election means for density and housing policy.

“Clearly it’s probably time for a reboot from when I started versus where we are today,” Rice said. “Neighborhoods have changed from where we were before.”

That view didn’t stop Rice from supporting Harrell. The same goes for the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, which often talks about its support for density and reforming single family zoning — especially as an alternative to new business taxes — but seems to find other causes around election time, such as the Compassion Seattle charter amendment this time around.

“The chamber’s new CEO, Rachel Smith, said that is still true today,” Kroman wrote. “At the same time, when asked about Harrell’s campaign statements, Smith agreed with him that talk of eliminating the zones was not helpful.”

“I think talking in absolutes is both inaccurate and can be polarizing,” Smith told Kroman. “I think it’s kind of like saying, ‘We’re going to ban all cars from the city.’ Do we need to take serious measures to reduce our carbon emissions from vehicles? Of course. Should we tell everyone we’re going to ban cars from the city next year? No. It’s not realistic and it’s not going to inspire people to action and change.”

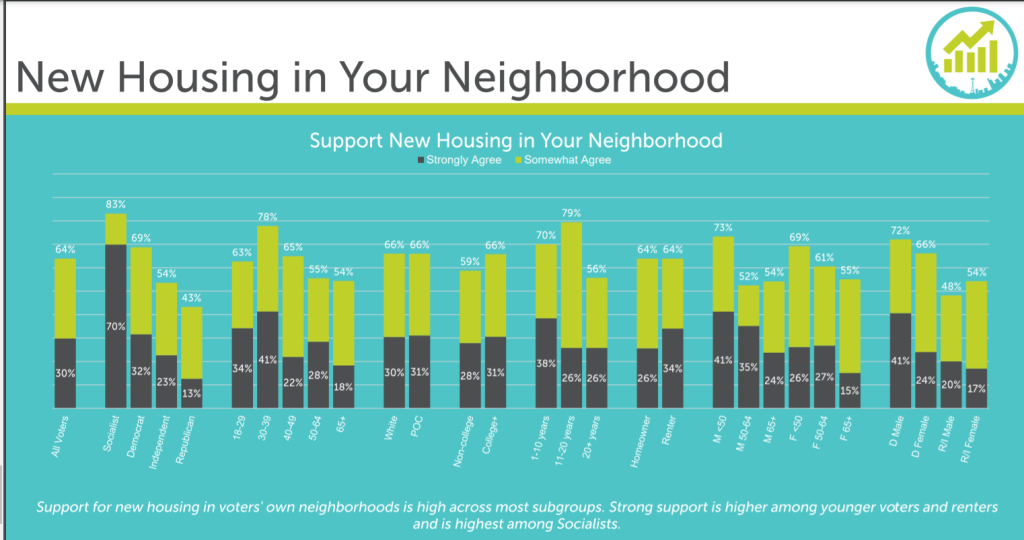

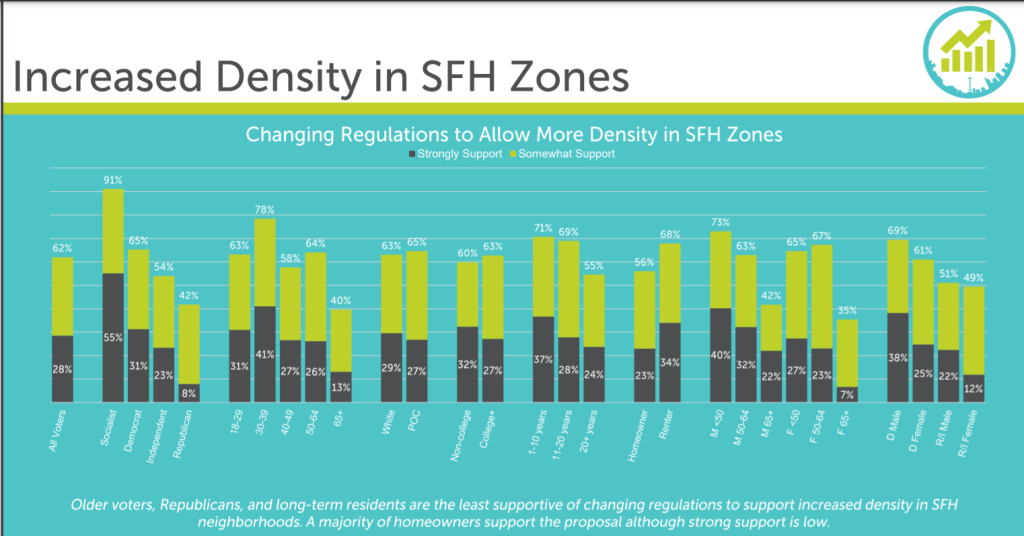

Still, polling shows support for single family zoning reform.

“Polling shows support for more density,” Kroman wrote. “In a recent survey conducted by the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, 64% of respondents said they supported new housing in their neighborhoods; 62% favored allowing duplexes and triplexes in single-family neighborhoods.”

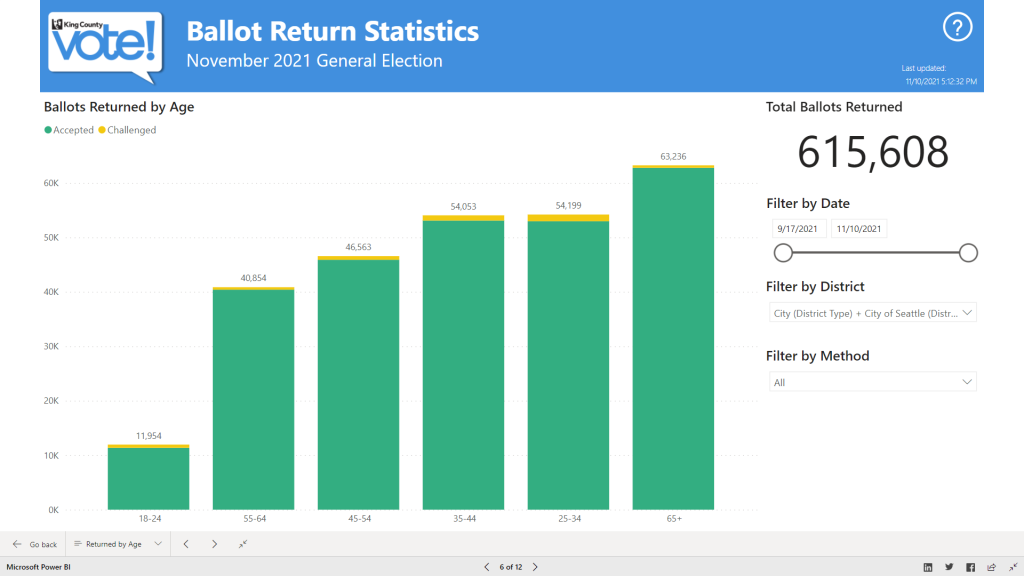

Unfortunately, the people who are most likely to vote — seniors — are those least likely to support changes to single family zoning.

Off-year elections are unlikely to change the mayoral outcome given Harrell resounding 17-point win, but it does change the contours of the debate and ensure the electorate is less likely to support zoning changes than an even-year electorate with higher participation from younger voters and renters. As a result, our system rewards candidates that follow a backward approach and delay action on housing affordability.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.