Foss Maritime closed its ship repair facility this week. Located on the Ship Canal at the north end of Interbay, the yard provided dry dock maintenance to the company’s tugs and marine transportation vessels in Puget Sound.

The company, founded in Tacoma in 1889 by Thea Foss and later expanded to Seattle, issued a statement citing a “regular evaluation of business lines” for closing the dock. The employees will receive a legally required 60 days of salary and benefits. The company will maintain maritime operations in the region, but will use other shipyards for maintenance and repairs.

The closing of Foss’ dock is terrible for the 115 employees laid off, bad for the industrial maritime neighborhood, and a psychic blow to Seattle’s image of itself as a working seaport. But it will be worse if we don’t see it as a predictable outcome of regional land use decisions and the evolution of maritime industry. Only then can we take steps to prepare for the very different maritime future that’s on its way.

Industry Across Cities

We have covered the land use issues in Interbay a few times. The neighborhood is wallowing under a zombie plan. The transportation system is out of whack with little hope. The largest available tracts are being envisioned for residential and commercial uses. The city’s current attempt to fix industrial zoning is very limited, first and foremost by efforts to jump ahead of new regulations.

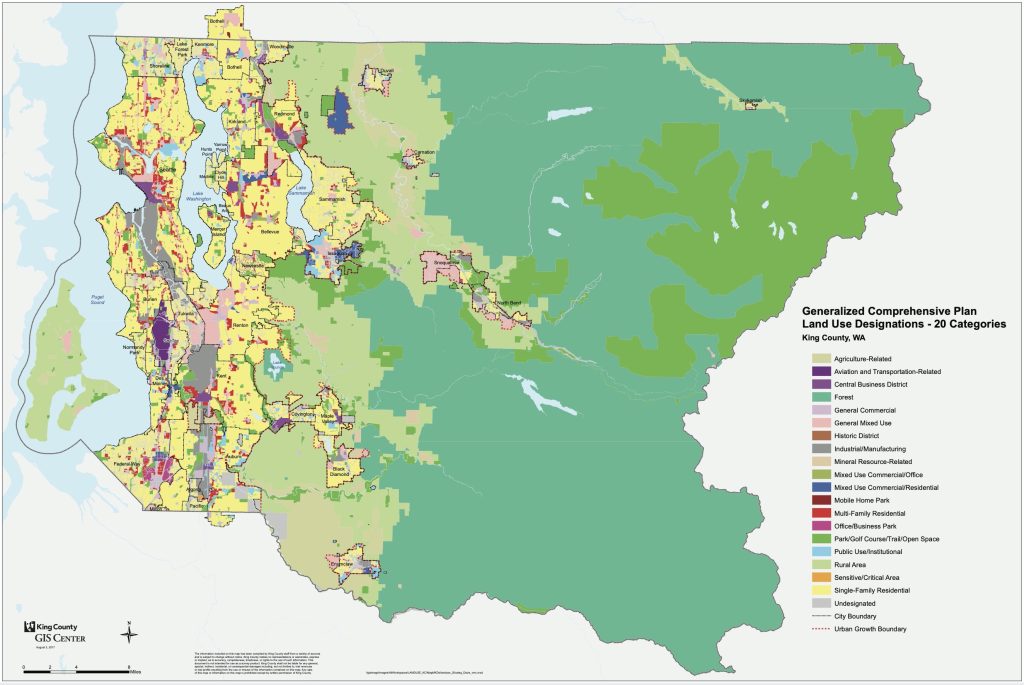

What we don’t often see is a big picture of how industrial lands are connected across the city and region. If you look at an image of King County land use, you’ll see that Foss and Interbay are located at the very northern tip of a long line of industrial lands. Stretching north from the Pierce County line through the Kent Valley, SeaTac, and Tukwila, this industrial stripe is only broken by Southcenter and Downtown. Southcenter is a mall surrounded by mixed use industrial parks. But if you consider industrial lands to be “employment” rather than “pouring out pollution,” that makes Downtown just as much an industrial neighborhood as the others. The line is continuous up to Ballard, and then stops.

That means the success of Seattle’s industry is fundamentally reliant on the industrial rules of ten other jurisdictions and vice versa. Improvements to maritime infrastructure depends on regional entities like Puget Sound Regional Council. Except for Kenmore at the north end of Lake Washington, none of those other jurisdictions have industrial maritime facilities. There’s a direct competition for resources and employers between the cities that share this industrial corridor.

Burdens of Employing People

The employment component of industrial lands planning is vital because it emphasizes how industrial uses are molded by two very particular forces. They’re land intensive, which in Seattle means very expensive. And they’re human intensive, which in Seattle also means very expensive. The closure of the Foss shipyard appears driven by that employment component, as has been the case with other shipyards in the area. Long time industrial workers, often represented by unions, maintain deserved and extensive health benefits and pensions. In competitive markets, there is pressure to reduce these expenses.

Foss itself is a wholly owned subsidiary of a company called Saltchuk, who owns a number of other transportation firms. Interestingly, one announcement of the closure mentions that Foss does not own the shipyard property. Public records show the landlord is a company called Ewing Street Shipyard, LLC which traces back to another company called Ilahie Properties, Inc. The directors of Ilahie are also directors of Saltchuk, though Ilahie does not appear on the company’s website. It’s notably specific to say that Foss does not own the land when it’s tied to their corporate umbrella.

All that totals up to this small industrial property being at the heart of the political and economic entanglements of early 21st century capitalism. Jurisdictions playing a zero sum game of business and tax competition. Corporate ownership playing shell games and blocking pension payouts. And 115 people having their last check the week of Christmas. It’s a cocktail that gives zero hope of evolving in the face of the changes coming soon.

The Shape of Changes to Come

It’s change that starts and ends with climate. The entire reason that the region’s industry exists is the water, which is heating and rising. The first things threatened by climate change are the seafood and fisheries that form the core of Seattle’s maritime businesses. As the water rises, the port and rail facilities will be next. The cargo container ports are at current sea level. The region’s primary rail line runs along the edge of Puget Sound, already prone to landslides. The future of industry depends on coordinated responses to replacing all this infrastructure.

This is not the first evolution that Seattle’s ports have gone through. Visitors downtown enjoy Ivar’s fish and views from a ferris wheel on docks that once were used for freight. As shipping evolved from longshoremen taking barrels off boats to cranes moving truck-sized containers, the port founded new facilities south of downtown. Now Piers 54 through 70 are entertainment and tourist venues.

What’s different this time is the number of players involved. The port terminals moved a couple blocks south within the city. But now we’re talking about industrial interests spread across the patchwork of municipalities in the region. We’re talking infrastructure changes that will relocate massive investments, creating winners and losers. All in the context of corporate and regional governance where one hand can blithely say “it’s not our land” when the other hand is holding the deed.

Foss’ closing of their Ship Canal facility isn’t the leading edge of a trend. It is a completely predictable business decision in the current context. What should be alarming is how broken that current context has become. Corporate shell games and patchwork municipal governance are leaving us unprepared for the massive overhaul that climate change will force on our employment areas. How dramatic the upheaval will be depends on how quickly folks understand their livelihood depend on abandoning the current fractured way of running things. Unfortunately this week, 115 folks understand it far too well.

Note: This article was updated on 11/8/21 to correct that Thea Foss founded Foss Maritime in Tacoma in 1889 and expanded to Seattle as the business grew.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.