Public records search suggests new Congressional requirements related to designing safer streets for walking and biking went unheeded.

Shortly before former President Trump left office, the Federal Highway Administration proposed an update to its Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), an influential regulation that controls a host of roadway elements including signs, signals, and markings.

“The notorious MUTCD,” joked Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg in March. “A seemingly dry and technical thing… could actually have a lot of consequences in terms of how people get around.”

Some of these consequences appear to include negative impacts on public safety. During the 2010s, when the 10th edition MUTCD was in force, the U.S. experienced unusually poor traffic safety performance for an advanced nation. The decade ended with the Covid-19 pandemic, when fewer people drove but the total number of crashes went up. In 2020, America’s crash fatality rate ballooned to nearly six times that of Sweden, and initial data suggests deaths will again rise in the first half of 2021. Traffic casualties have disproportionately affected Black, Latino, and Native American populations, along with those who walk or bike.

Experts have linked the problem to a host of factors including land use patterns, truck, and passenger vehicle safety. But in 2021, design standards received particular attention. When the MUTCD was posted on a government website, over 26,000 people commented, many dismayed by the lack of consideration for walking and biking in its guidance.

Citing recent experience, Ben Cares, a Senior Planner and Project Manager in Chelsea, Massachusetts remarked that in his work he wanted “to highlight areas where frequent pedestrian activity occurs, and to signal to drivers that these roadways are not just to be used for vehicular travel.” But some parts of the MUTCD appear to treat this notion with hostility. In the proposed crosswalk section, for example, the Department of Transportation standard reminds designers “the right-of-way is dedicated exclusively to highway-related functions.” Those seeking to employ “aesthetic treatments… should consider whether their use or design is appropriate for the right-of-way.”

Cares said the MUTCD’s “outdated and under-studied regulations have led to consternation and questions regarding the safety” of traffic calming and street beautification projects. In practice, such improvements can lead to “increased safety…visibility … and community cohesion.”

The gripe that codes sometimes stifle innovation is not new, but federal road standards were supposed to get better. A 2015 act of Congress should have made the MUTCD more conducive to safe and sustainable streets, but evidence suggests requirements were not implemented in the new manual.

Community Oriented Transportation Standards and the FAST Act

In 2015, Congress amended subsection 23 U.S.C. 109 of Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act to state that when developing design criteria for use on the national highway system (other than the interstate system), the Transportation Secretary, “shall consider… the publication entitled ‘Urban Street Design Guide‘ of the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO).”

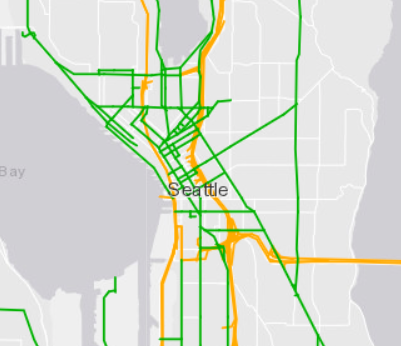

A little road context here. The highways subject to these guidelines include many highly frequented urban arterials in major population centers. The map below shows both national and state roads falling under the “national highway” descriptor in Downtown Seattle. Roads receive this classification for a host of reasons, including connections to other modes of transportation, like railways, or commercial or military installations, like seaports.

The Congressional amendment also strengthened existing language to require design criteria consider “access for other modes of transportation,” and consider the consensus of a landmark 1998 conference on ways to “Think Beyond the Pavement,” which had brought together representatives from environmental, bicycle, pedestrian, and historic preservation groups.

How does this relate to the MUTCD? The MUTCD is a design criterion used by the National Highway System and 23 U.S.C. 109 is one of three laws under which the MUTCD states it derives authority from. So the amendment passed by Congress should have required more consideration of other modes of transportation like walking and biking in street designs.

On October 6, 2016, now Federal Highway Administration Executive Director Thomas Everett sent an email to the administration’s engineers – those who in practice manage the Secretary’s design criteria – alerting them to the changes, including guidance on designing for pedestrians and cyclists.

What happened afterward remains mysterious, but it appears that new requirements related to safer streets for walking and biking went unheeded. In the proposed MUTCD, an array of design options and suggested changes from FAST Act sources are unexplainably absent. Some MUTCD sections even conflict with legally referenced publications and the peer-reviewed research supporting them.

Safe street treatments missing from the MUTCD

Many prominent safe street treatments referenced in NACTO’s Urban Street Guide are missing from the MUTCD. Examples include:

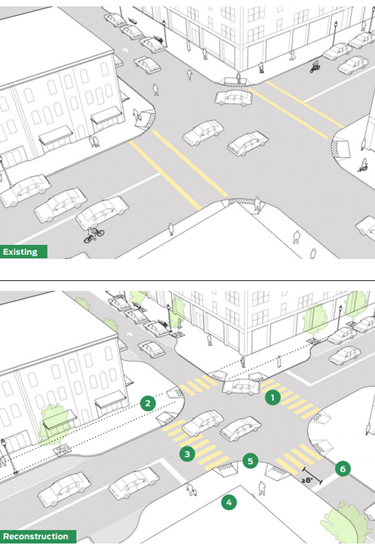

Shared Spaces: A woonerf style shared space in Princeton, NJ. By designing streets to be more like driveways and patios, additional public spaces can be gained. This street treatment has been shown to reduce speeding and improve traffic safety in numerous studies.

Sidewalk Level Bikeway: By integrating cyclists with pedestrians, the hazard of driver encroachment into a bike lane can be virtually eliminated, as can the risk of colliding with a curb.

Raised Entrances: This design can improve street aesthetic while making walking and bicycling more comfortable, since non-motorized users do not need to go up and down at each corner. The raised entrance also acts as a natural traffic calming device.

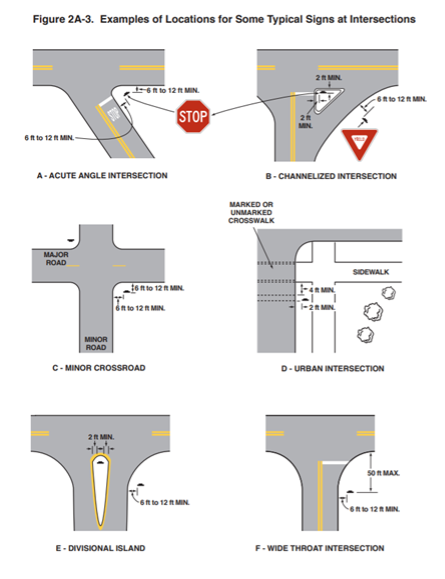

Corner Ramps: The NACTO Streets guide describes walkability and safety reasons not to use corner ramps along major roads. The proposed MUTCD contains many new diagrams with awkward corner ramp alignments.

Crosswalks: The NACTO Streets Guide states along larger roads “crosswalks should be the norm at intersections.” (NACTO, p 110). However, many MUTCD diagrams are missing crosswalks.

The Urban Street Design Guide is 193 pages long, so it’s infeasible someone could have thoroughly checked for conflicts between it and the several hundred page MUTCD without taking notes. Proper consideration is also a requirement of law, so there ought to have been some documented research or literature review behind decision-making.

The Federal Highway Administration has so far not released any records showing what, if anything, was changed based on the legally referenced guiding documents.

To shed light on agency reasoning, I filed a Freedom of Information Act request, which sought several items, including any documents “showing consideration” of the Urban Street Design Guide in MUTCD drafting.

No record of evaluation

To process my request, letters of support were needed. Patrick Conlon, president of the Jersey City, New Jersey based advocacy group Bike JC wrote to Federal Highway Administration, “We believe a bike-friendly city is safer for everyone. We are therefore quite concerned about the possibility that certain bike safety treatments – especially those related to complete streets and signage – may have been omitted from the MUTCD.”

Conlon went on to express alarm at “contradictions” between the MUTCD and best practice publications referenced by the FAST Act.

The initial request was sent in late February 2021, and asked documents to be delivered in advance of the May 14th comment period closure. On the morning of May 14th, Mark Kehrli, Director of the Federal Highway Administration’s Office of Transportation Operations wrote back that they were still looking for records, something they are still apparently doing as of October. But Kehrli’s office had completed part of the search.

Concerning the bicycles section, where many of the missing treatments from the NACTO Streets Guide would go, a search for if the NACTO Guide was ever downloaded, purchased, or borrowed by the person in charge of the chapter “revealed no responsive records.” There was also no record the task of reading and evaluating the NACTO guide’s treatments was delegated to anyone else.

FOIA Binder Update2 With Urbanist Logo by Natalie Bicknell on Scribd

Will the MUTCD be struck down in court?

“We’ve known for years that the MUTCD enshrines dangerous design practices into law,” said Sara Bronin, professor of law and city and regional planning at Cornell University. “The [Federal Highway Administration’s] latest proposed update perpetuates many of the discredited features of the current version.”

If the Federal Highway Administration did not write the MUTCD in accordance with law, it’s possible the standard could be struck down in court. When asked, Professor Bronin, who is also an attorney with expertise in federal design standards, did not want to speculate publicly on the chances that a legal challenge would succeed. Bronin, however, had no reservations about what the agency ought to do.

“The only sensible solution is to follow the science behind modern transportation research to completely overhaul the MUTCD,” she said.

“Here’s to us making strong strides this round and in future years,” remarked Dennis Markatos-Soriano, Executive Director of the East Coast Greenway Alliance. Markatos-Soriano did not directly answer if he thinks the Federal Highway Administration drafted the MUTCD improperly, instead, pointing to an existing comment expressing hope the Biden administration would support an MUTCD overhaul because it matches their own goals.

“We respectfully request that FHWA reframe and rewrite the MUTCD… Doing so will allow FHWA and the Biden administration to make strides towards equity, sustainability, and vulnerable road user safety.”

The National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, a non-profit group that supports MUTCD development, did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Scott Brody (Guest Contributor)

Scott Brody holds a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering from Rowan University and a Master of City and Regional Planning from the Rutgers Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy. He is currently finishing a second Master of Civil Engineering. His research focuses on comparing design standards from the US to those around the world.