In just a few days, world leaders will gather in Glasgow at the United Nations Climate Change Conference, where they will discuss how to accelerate emission reduction targets. This month also marks an anniversary for Seattle’s climate change commitments: four years ago Seattle was one of a small group of 12 cities worldwide to sign on to the C40 cities Fossil-Fuel-Free Streets Declaration. That declaration included two key commitments: only purchasing zero-emissions buses starting in 2025 and creating a “major area” of each city that is free from emissions by 2030. This declaration was signed by Seattle’s unelected interim mayor Tim Burgess, and at the time, Seattle was the only city in the United States to sign it. Since that time, the declaration has been signed by nearly all of the 40 cities that make up the C40.

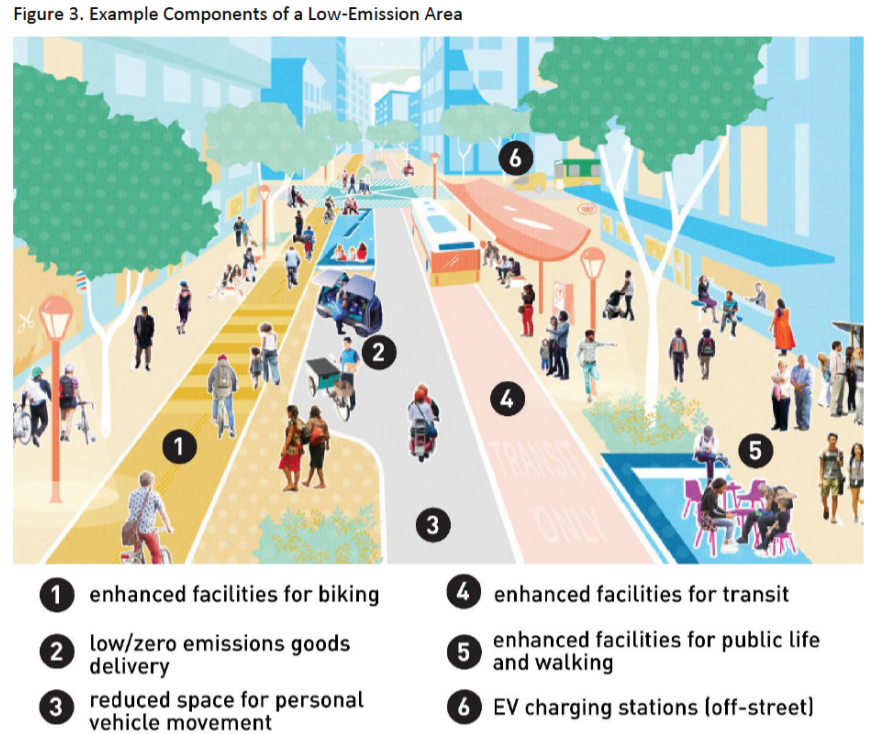

Last year, an update from C40 detailed the progress being made to achieve the goals laid out in the declaration and identified distinct implementation strategies that cities are pursuing. Cities like London, Barcelona, and Seoul are implementing vehicle regulation cordons, with higher charges to enter city cores for vehicles that emit higher levels of pollution. By 2030, a zero-emissions area (ZEA) won’t allow entry for any fossil-fuel vehicles. In Seattle, Mayor Durkan’s top-down approach to the idea of implementing a congestion pricing charge in Downtown Seattle, which she pledged to do by this year shortly after taking office, has produced no results or tangible product.

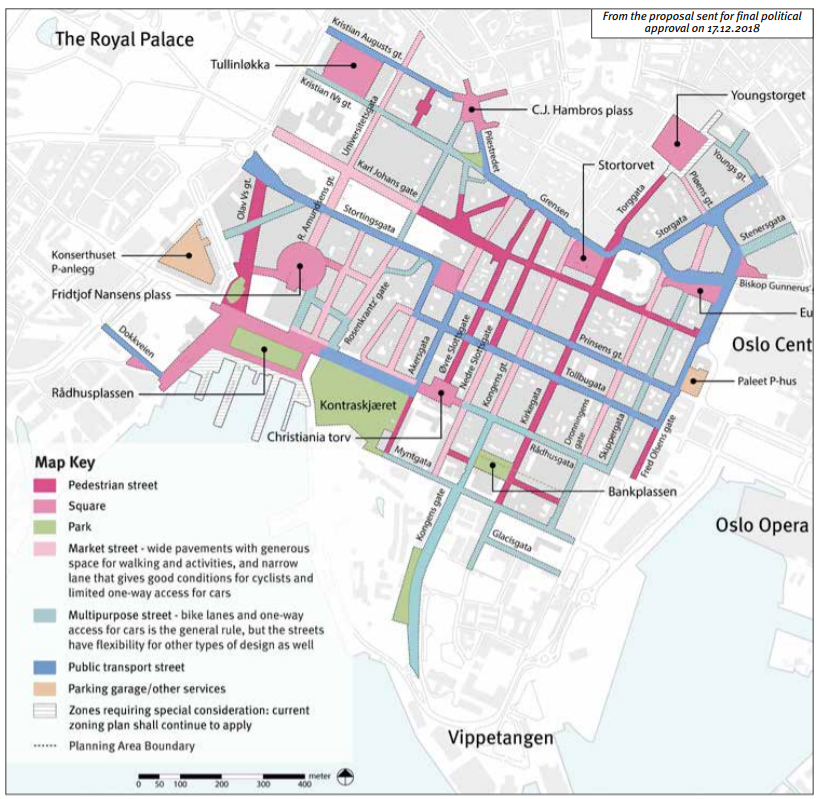

Meanwhile, other cities like Oslo are moving forward on a district-based approach. In early 2019, Oslo removed nearly 700 parking spaces, adding bike lanes, parklets, greenery, and seating in their place. Many streets inside the district were fully pedestrianized. “In Oslo, we are aiming to reduce our CO2 emissions by 95% by 2030. To succeed, we will continue to step up investments in public transport, bicycle paths and pedestrian walkways,” Mayor of Oslo Ramond Johansen wrote in “We Have the Power to Move the World: A Mayors’ Guidebook on Sustainable Transport.”

Seattle was not included in that status update in 2020. For a long time, it looked like Seattle’s promise had been relegated to a shelf somewhere, never to be heard about again. Then in early 2021, it popped up in the City’s “Transportation Electrification Blueprint,” but without much detail on what the City was doing to achieve its promises.

Now, The Urbanist has obtained a memo draft submitted to Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Director Sam Zimbabwe in April. Since it was released as a draft, much of the document has been redacted by staff with the justification that the information is related to the deliberative process. That means that if the document proposes specific neighborhoods or streets that might be a good fit for the strategies under consideration by the department, we don’t yet know about it. But we can still learn a lot about how SDOT is moving forward with creating areas of our transportation system with low levels of vehicle emissions.

It looks like the city is keeping its primary example of a “Green and Healthy Street” close to the vest for now, but two other strategies are included in the memo. These both use SDOT’s 2020 Covid-19 interventions as jumping-off points: utilizing street space in commercial business districts (like with the Ballard Avenue cafe street or The Patio common restaurant seating area in Columbia City) and designating residential streets local-access-only with the Stay Healthy Street program and the Home Zone pilots programs. It’s not a huge stretch to guess that the final pilot concept would be on a downtown street, but we don’t yet know for sure.

One of the key parts of the document is an acknowledgement of the legislative hurdles that stand in the way of emulating pedestrianized and low-emission streets enacted elsewhere. Federal legislation currently prohibits cities from regulating vehicles based on emission standards, fuel type, or vehicle weight. State law does not allow cities to set speed limits that are lower than 20 mph, prohibiting Seattle from following in the footsteps of Barcelona by limiting speeds to 6 mph on pedestrianized streets. And state law also prohibits pedestrians from walking in the roadway when a sidewalk is present — a hurdle SDOT cleared on its Stay Healthy Streets with “Street Closed” signage, but which deserves a better fix.

Seattle’s 2021 state legislative agenda says the city supports “local autonomy in adjusting speed limits” and “decriminalizing pedestrian activities such as loitering and jaywalking” and hopefully the City’s lobbying can make headway on these issues if they become higher priorities for the mayor and city council.

Also notable is this acknowledgement in the document: “Currently, the transformative work outlined in this Action Plan is largely unfunded.” Improving public health by reducing emissions exposure deserves its own funding source, but spending years figuring out how to implement this has led to countless missed opportunities. How many projects during the past four years could have been integrated into this work? The $39 million Pike Pine Renaissance project is one that comes to mind, a project that is leaving on the table easily pedestrianizable streets around Pike Place Market.

The proposed measures of success in the memo, outcomes like increased bike and pedestrian traffic, an increase in use of public space for “lingering,” and a reduction in collisions, do not include metrics related to air quality. Ignoring the air quality benefits might mean that a four year delay on a program like this isn’t consequential, but it does every resident in our region a disservice. In Washington, one out of every seven residents live within a quarter mile of heavy traffic roadways and their health outcomes are impacted by that fact. Seattle leading the way on reducing vehicle emissions and encouraging low-emission freight would have benefits around the state, and there really isn’t any time to wait.

The memo notes that the rest of 2021 will be spent collecting data to inform site selection and on community and business outreach. Of course, if that remains on track, that information may be ready to hand to a mayor who is ready to run with it, or a mayor who will shove it into a drawer for another four years.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.