(From a certain point of view)

The Urban Land Institute, the world’s largest network of real estate and land use experts, held its fall meeting in Chicago this week. Many attendees participated for their first in-person conference in two years. The group’s updated mission — to shape the future of the built environment for transformative impact in communities worldwide — was on full display at the conference. Big plenary sessions and luncheons. Networking opportunities and swag bags. All on the beautiful shores of Lake Michigan.

Not me. I streamed the presentations remotely. It drained a good amount of the fun of conferences to participate from my kitchen table, so you’re stuck with a breakdown of what was actually said at the sessions.

I’m a big fan of ULI. I went through their Leadership Institute in metro Washington D.C. a few years ago and benefited from insight of their advisory services. The group is one of the few that doesn’t cloister building and financial industry folks from academics and government apparatchiks. It lets regulating people and design people and money people talk to each other as peers, not competitors.

The ULI Fall Meeting lived up to that. The sessions were panels of very smart folks downloading an enormous amount of information on the what, where, and why of big real estate deals and the ways companies and cities are coming out of pandemic.

The upshot is that the two years of pandemic have been too short to change many types of real estate products. The things that changed were not necessarily the footprints, but the users. In Nashville, a hotel operator backed out of Nashville Yards and now those hotel rooms are being built as residential units. Horton Plaza in San Diego is going to be a life sciences campus instead of a “creative office” complex. People who could move found places of affordability and access in secondary cities, but there are longer term averages in rent and price for construction, and the market is beginning to revert towards them.

Cutting across a lot of presentations, it was interesting to see several themes frequently pop out. More than the overall discussion of where office or residential markets are going, these are the three issues to watch.

TREND 1: Build to Rent

An entire session was devoted to Single-Family Rentals – Build to Rent. These are tracts of single family homes developed with the purpose of being held by an investment firm and rented out to individuals. Some firms have a broader SFR-BTR (terrible abbreviation, sorry) purchase mandate, including existing properties or townhomes. It is, at the moment, a heavily suburban Sunbelt phenomenon with private equity firm backing that carries a lot of levels of troubling.

The session devoted to SFR-BTR (ugh) was very interesting. Panelists pointed out the market is maturing to the point that it’s changing. Specialized firms are systemizing their paperwork and construction, a move to scale. However, they’re no longer getting discounts for buying in bulk. Reports of billions of dollars moving into the sector are frequent, but not wholly accurate because it’s difficult to find the properties to consolidate into a portfolio. The property acquisition mindset is eerily tilted also. Like any homebuyer, investors are looking for good schools, commute times, and resale values. But their comparables are apartment rents and the calculation is as an income stream, not home equity.

The topic came up in other residential real estate talks. Concentration in secondary and Sunbelt cities raises the question of negative impacts on unprepared markets. The massive Lakewood Ranch community of Florida offers single-family rentals, which Senior Vice President Laura Cole called a way for potential buyers to “test run the communities.” In all, SFR-BTR (gah) looks like a gold rush in the near term, one that may focus immense money in some places that quickly goes elsewhere. The question is whether jurisdictions have a role to play in managing them because the towns will be stuck with the impacts of these developments.

TREND 2: Headline Noise

ULI held separate presentations on mixed-use entertainment districts and office trends with a focus on spending 18 months empty. Entertainment spent the time eating losses and trying to do public services (vaccine clinics in stadiums) while recouping some funds (smaller, vaccinated events). Offices are trying to find a path to widespread return. The coastal cities are lagging behind those cavalier cities that opened earlier. For big companies with multiple locations that variation will offer a contrast in productivity.

Between office and entertainment, the overlap centered on discussions of bringing people back and ways to make them feel safe. Space does. Open air does. Transit does not. It brought up the question of whether people would return to downtowns easily. Here, the entertainment crowd informed the office. The last few weeks have seen full stadiums in slow-to-reopen towns like Boston and San Francisco. Yes people will come back, and ball games may allow folks to reacclimate to transit. When it comes to championships or career promotions, people are expected to FOMO themselves back on the train.

But, will they feel safe in all these dead coastal downtowns filled with tents and people sleeping on the street? The evening news and the local fish wrap will tell you this perception of decrepitude is the leading thing keeping workers and tourists out of our city. Such simplification was completely dismissed by presenters as “headline noise.” Mixed use neighborhoods where people live, even downtown, are doing well while empty business districts have gotten crushed. Activity will solve the image problem, and activity is coming.

Deeper than pictures of tents is the reality of homelessness. The message for coastal cities from every ULI panel was housing housing housing. Every discussion of rent said that secondary cities were growing because they were affordable. Every discussion of labor used the phrase “despite the cost of housing” in coastal costs. There was not talk about overwrought building codes or expensive reviews or even taxes. There was only the need to remove limits that prevent development of dense, affordable housing.

TREND 3: Amenities

What do offices and neighborhoods look like post-pandemic? As said, the blip was too short to have a lot of change and there is a movement back to normal underway. Pushing that is how draining the pandemic experience was. Anthony Chang, Managing Director at Stream Realty Partners, pointed out that working from home is using up “cultural capital” of offices. These are the intangibles, trust, even inside jokes that a new employee gains from being around other staff. This is an amenity missing from remote work.

Those office agreements may look different on return. Speakers on office space trends did not think the small desk/space layout would change much, but mentioned responsibility for the amenities of the office were being reversed. Instead of community spaces or meeting rooms being the responsibility of individual tenants, they were being pushed onto the landlords. Some suggested property managers would move towards being hospitality providers, seeing concierge service, events, and bars for their tenants.

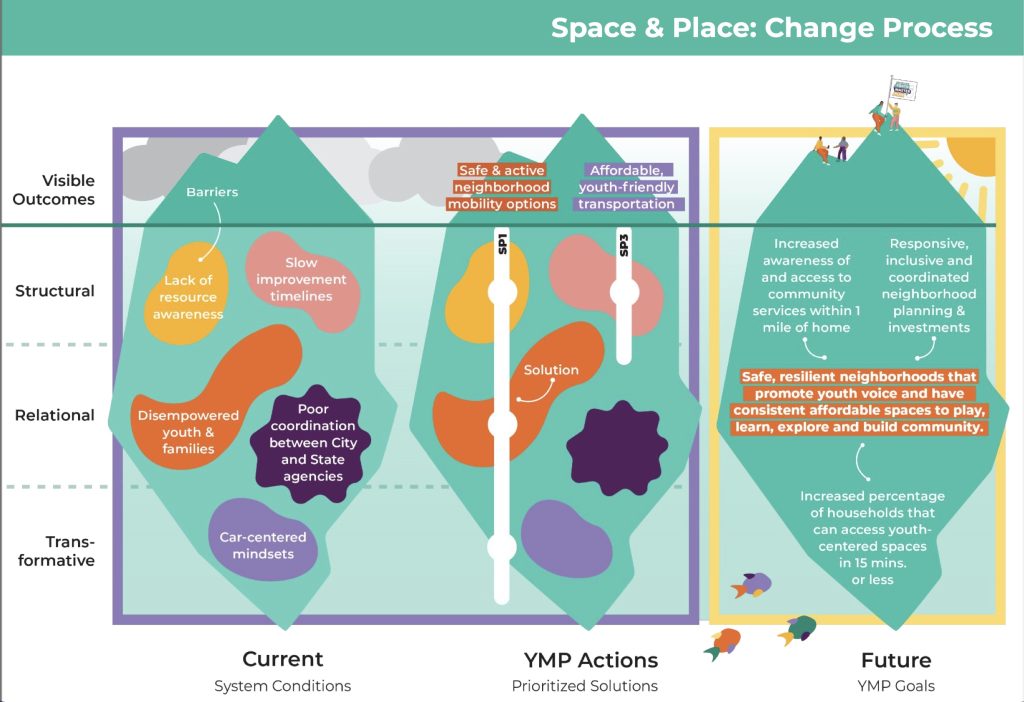

A fascinating panel on New Orleans’ work to become a child friendly city drew the word amenity to its widest use. Entering office in 2018, Mayor LaToya Cantrell promised to develop a Youth Master Plan. Pulling together transportation money with a community outreach program, the city asked kids how they get around and where they want to go. Then, based on the work of design and engineering firm Arup, New Orleans is building out a city for everyone.

Arup produced a report that breaks down child friendly cities into “everyday freedoms” and “children’s infrastructure.” The first is about getting to important things – socializing and play – with independent mobility. The latter is the network of spaces, streets and nature that make up for a healthy public realm. Together, they make a greener, safer, resilient place that retains healthy families. If this doesn’t sound like making a city better for everyone, catch up please.

What I heard throughout these presentations is a changing use of the word “amenity.” It’s always been something desirable, extra space or a special facility. What’s different is whether the amenity is an option or a requirement. Too many things have been put into the optional category, like safe places to cross a street, dependable transit, or clean water. Folks needing to fight for them are beginning to say that’s not enough. Post-pandemic, amenities are not optional.

What is the transformation?

The thing that stuck with me through the entire conference was the opening words of keynote speaker, former Obama economist Austan Goolsbee. He asked whether we will look back on the pandemic and see it as a journey or as jury duty. That is, will the pandemic go down in history as a transformational path to a new place, or an obligation that was endured. He was leaning more towards jury duty.

Goolsbee broke the trends into two flavors. Any trend accentuated by the pandemic will be accelerated. This includes online purchasing and work from home. Any trend reversed by the pandemic will be temporary. This is counter to the “Death of the City” thread, where we’re already seeing business pick up in downtowns as they reopen while business never left mixed use neighborhoods.

In short, we’re going to keep going the way we’re going, except where we’re not.

This is the exact same assessment that could be made on 99.995% of all days throughout 5,000 years of recorded human history. The remaining 100 days are what we learn in history books.

Of course, millions of words have been spilled on figuring out when those 100 days are coming, labeling them Black Swans and Tipping Points. It’s hard to ask for speakers at trends and outlooks presentations to predict absolutely singular points in human history ahead of time. Anyone who saw those 100 important days of human history beforehand are the ones we learn about on the next page of that history book.

What felt limited in the ULI conference trend discussions are how middle-of-the-road they were. They were revenue recovery and finding value in the rebound. Quiet coastal downtowns are ripe for picking up affordable real estate investments before they boom again. Interior secondary markets are currently a value, but rent and salaries are reaching parity. Leasing companies are having success in shorter contracts with more amenities.

Some presentations had discussions of breakthrough technology, but it was modular housing and 3D printed buildings that look very similar to what’s being built now. Some talked about big data and analytics that extrapolate current markets and trends. It was forward looking in the narrow context and service of housing markets and community systems that we see are set up to fail in the face of pandemic, climate change, and civic unrest.

The conservatism is understandable given many of the speakers work for giant real estate houses and accounting firms. They have a depth of knowledge and resources to see where we are on many historic curves. But if those curves are about to break, are these folks prepared to tell us? How transformative can their data be?

Perhaps that calls us to appreciate the deep dives, then look sideways through for real insight. We have to understand the coastal city pressures that have created a build-to-rent demand in the Sunbelt. We have to lower the noise of short-term perspectives to see the underlying issues leading to homelessness. We have to remember how people are fighting for necessities that others call amenities. And from that we can take an important lesson. A safe, affordable place to live in a great neighborhood is the most transformative idea of all.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.