It’s City budget season and the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) is seeking to boost funding for tiny house villages that shelter people experiencing homelessness. LIHI, the sole operator of tiny houses villages in Seattle, is asking supporters to testify before City Council on Tuesday, October 12th, in favor of funding three additional villages and increasing funding for the existing tiny house villages to ensure “equitable standards are maintained” across the sites.

However, the Lived Experience Coalition (LEC), an organization whose membership is made up people who have experienced homelessness, has become increasingly vocal in its opposition to expanding the tiny house model, arguing the tiny houses are “in fact sheds rather than tiny homes.”

“This is not HGTV tiny houses we are talking about,” Zaneta Reid, Director of Operations for LEC, said. “We don’t want these villages to become a dropping place for people are struggling and can’t advocate for themselves.” Reid spoke to The Urbanist after a rally for a proposed tiny house village in South Lake Union in September. When asked if LEC is advocating for specific alternatives to tiny house villages, Reid emphasized that “real affordable housing” was the only solution for Seattle’s homelessness crisis.

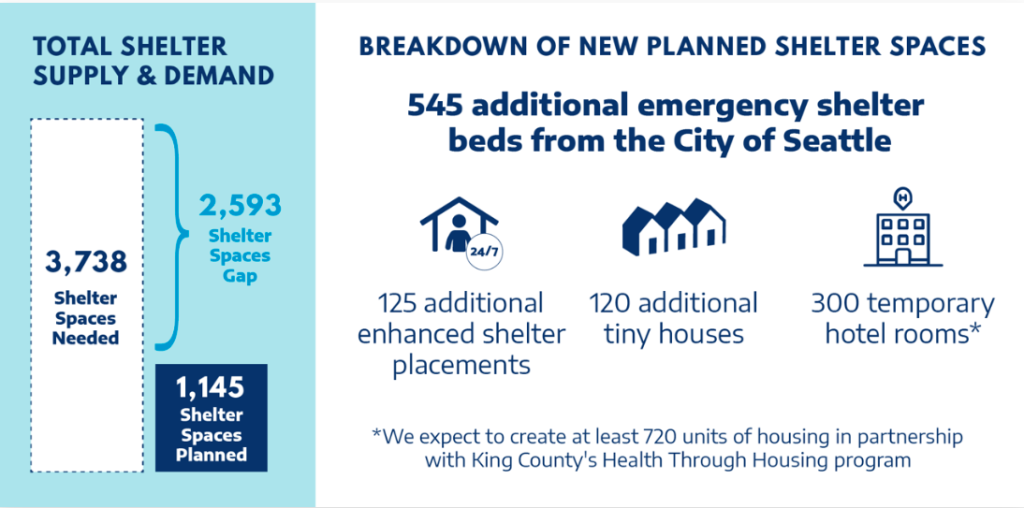

Few would argue against Reid’s assertion that what people struggling with homelessness really need is a home: a place where they can feel comfortable, safe, and have access to the basic amenities like an individual source of running water. However, with more than 3,700 people sleeping unsheltered each night in Seattle according to estimates, tiny house villages remain an interim solution some Seattle leaders wish to expand.

Case management and services

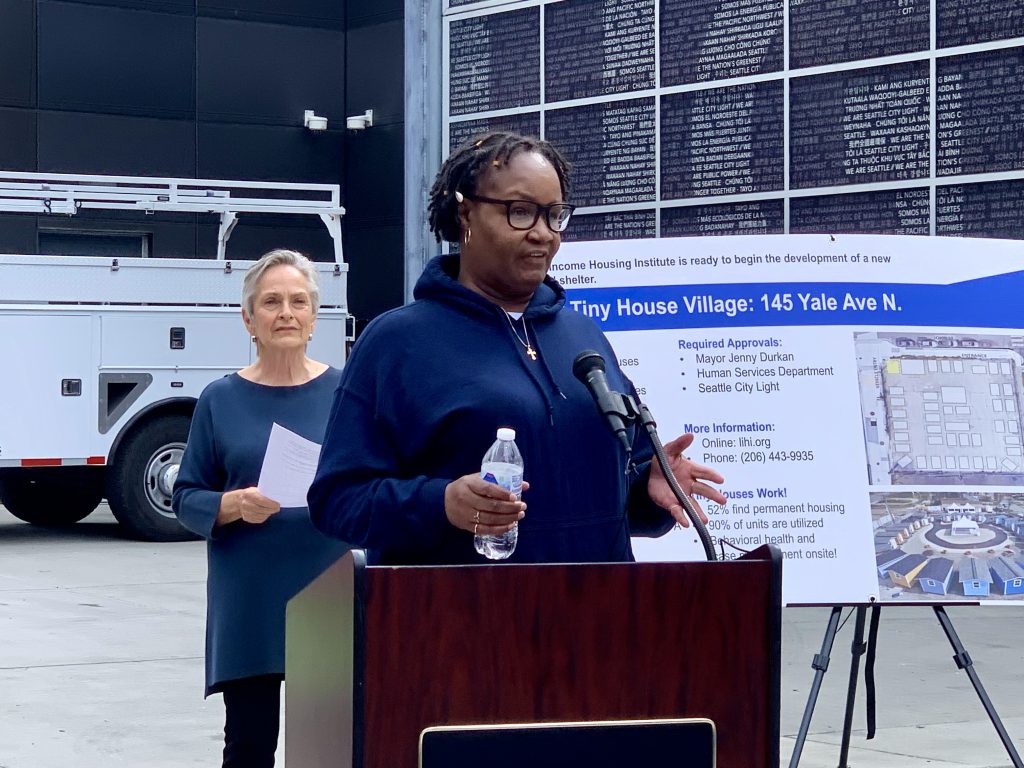

At the rally in South Lake Union, Tracy Williams, a former tiny house village resident and current LIHI employee, spoke passionately to the crowd about the positive change living in the tiny house village brought to her life. Williams was not the only former or current resident to come out to express support.

More than a dozen residents were amid the crowd, including Ryan Hoess and Kimberly Phillips who were both enthusiastic to speak about their desire to see the tiny house village model expanded.

“I came from sleeping outside in doorways for years,” Hoess said. “Living in the village made me feel human again.” Hoess further explained that he is now employed at a coffee shop, something that he felt would not have been possible before moving into the tiny house village.

For Phillips, access to services was the greatest benefit offered by village life. “I think the whole premise is great,” Phillips said. “You have a case manager who can help you get into a home. They help you, but they don’t do it all for you. You also have to make an effort yourself.”

Still Phillips, who is Canadian and moved to the U.S. with her American husband a few years ago, conceded that difficulty in navigating a complex social system makes the case management assistance invaluable. “I could see a lot of us getting stuck homeless here for a long time without the help,” she said.

Neither Hoess or Phillips had been living a tiny house village for an extended period of time, but they had heard stories of people moving from village to village, as well as of differences in village management and services between villages. Even so, they both expressed gratitude for having the chance to live in a tiny house village and a desire to see that opportunity extended to more people confronting homelessness. Yet, despite pledges of support from Seattle leaders, progress on tiny house village expansion has remained slow.

1,000 tiny houses that never materialized

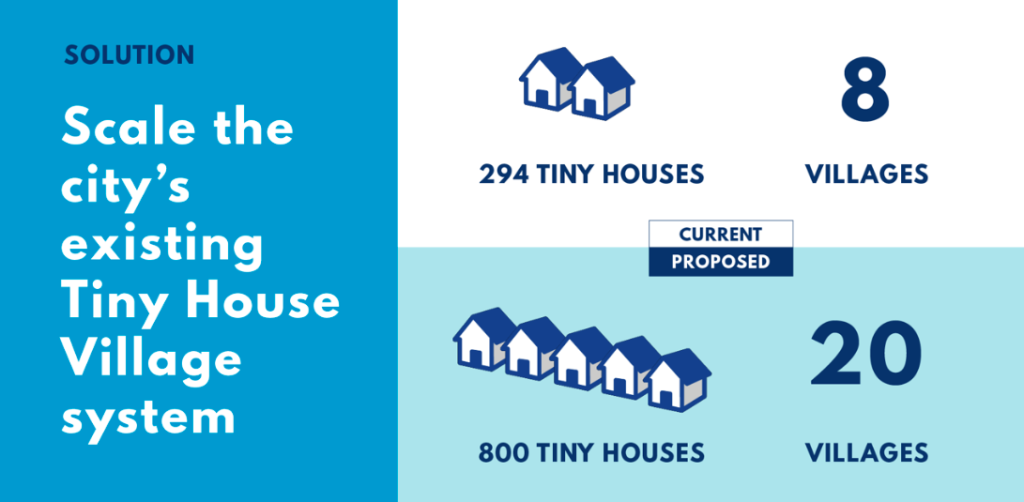

On the campaign trail back in 2016, Mayor Jenny Durkan promised to build 1,000 new tiny houses during her first year in office. She ended up building 73 tiny homes in her first year. Nearly at the end of her four-year term, the current number of tiny houses in Seattle tallies to roughly 295, with another 90 more tiny homes becoming available in the near future as two additional villages in North Seattle open to residents.

However, Mayor Durkan has not been the only politician to hit a tiny house construction impasse. Last January Councilmember Andrew Lewis (District 7) sought to rapidly increase the number of tiny houses through a proposed program emphasizing public-private partnership called “It Takes a Village.” Under his plan the number of tiny houses in Seattle would have increased to approximately 800 by the end of 2021.

Illustrating the difficulty of tiny house village expansion, despite having raised over $2.5 million from private donors for the campaign, Lewis’s effort stalled. According to Lewis, the State Environmental Protection Act (SEPA) presented the biggest hurdle. In an article by King 5 News, Lewis complained that SEPA delays “[d]ue to frankly a lot of unnecessary things that temporary villages should not be subjected to in terms of needing to complete arduous, lengthy and red tape-filled environmental reviews that are really designed for structures that are going to be permanent.”

However, SEPA is not the only road block to slow down tiny house village development. Take for example the case of the proposed tiny house village in South Lake Union. The startup costs of the village have already been mostly covered by a $150,000 donation from Mirabella, a not-for-profit senior living community located adjacent to the site, and a $100,000 donation from Onni Group, a mega developer in constructing a massive luxury development a short distance away on the former headquarters of the Seattle Times. However, the land identified for the village is owned by City Light, which uses part of the site as a pipe bending facility. The village project cannot move forward until City Light agrees to give up the land, something the department is unwilling to do before it can identify another site for pipe building work.

A bigger, more significant hurdle to expanding the tiny house village model may be ahead as well. The King County Regional Homelessness Authority (KCRHA) will be taking over the City’s homelessness-related contracts in 2022, and KCRHA director Marc Dones has voiced skepticism about the tiny house model’s results in exiting residents into permanent housing in an interview with Publicola.

“But the things that make tiny house villages desirable may also contribute to the fact that people stay in tiny houses longer than any other type of shelter,” Publicola‘s Erica Barnett wrote. “Although the villages have a fairly strong track record for moving people into housing (between 27 and 65% of tiny house residents eventually move into housing, according to King County’s most recent performance data, compared to a 15% average across all types of emergency shelter), people tend to live in them for months or even years—far longer than the regional goal of 90 days.”

Arguably, tiny house villages are a victim of their own success and a lack of sufficient permanent affordable housing to move people into once they’ve completed their allotted stay in a tiny house.

A political football

The question of how many tiny houses Seattle should build has become a bit of a political football, with local leaders pitching different figures. While Mayor Durkan called for 1,000 tiny houses, mayoral candidate Bruce Harrell is calling for 2,000 units of “emergency, supportive shelter” to be built during his first year in office, a generalized term that lumps tiny houses into other types of emergency shelter, which, with the exception of hotel rooms, remained undefined on his campaign website. Harrell’s plan for addressing homelessness borrows heavily from the proposed “Compassion Seattle” city charter amendment that was ordered to be removed from the ballot by a King Count Superior Court judge earlier this fall for overstepping the bounds of charter amendment process.

City Council President M. Lorena González, who is also running for Mayor, has voiced concerns about people being unable to exit from tiny house villages into housing, and she has not put forth a figure for how many tiny houses she would like to see built. Instead, González’s messaging has emphasized the bigger goal of building affordable housing. A focus on the need to continue to expand affordable housing is consistent among other progressive City Council candidates, including incumbent Teresa Mosequeda (Position 8) and attorney and nonprofit leader Nikkita Oliver (Position 9).

Councilmember Lewis, whose “It Takes a Village” proposal called for the creation of 800 tiny houses, stated at the SLU tiny house village rally that while 295 tiny houses was too few, Seattle “might not need as much as 2,000.”

Given the difficulty so far in scaling up the model, committing to the creation of a specific number of tiny houses might be unrealistic. It does appear, however, that whatever the number of tiny houses increases to, the emergency shelter they provide will be welcomed by some people experiencing homelessness in Seattle. In her campaign website, mayoral candidate González referenced the need to “tackle homelessness with every resource available and on multiple fronts.”

Expanding tiny house villages alongside increasing production of affordable housing could be a sensible solution to the tragic, and seemingly intractable, problem of homelessness in the city.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.