Nicknamed the “city of trees,” Boise is an enigma in its approach to urbanism. A bike lane leads straight up to the steps of the state capital building, where a Republican majority legislature fills the benches and halls. Residents paddle kayaks and trout fish in the river running through heart of the city, not far from gritty Freak Alley with its provocative murals. Imposing stone churches and references to the city’s rich history of Basque culture juxtapose against western themed distilleries and restaurants serving up a multiplicity of dishes featuring Idaho’s famous potatoes.

Boise is also a city on the cusp of major change. While visible signs of growth may not be as evident as in other fast-growing western metros, the increase in population and influx of newcomers is beginning to make its stamp. Increases in density and challenges in housing affordability, as well as a desire to continue to attract new businesses and high income earning professionals, makes Boise an interesting urbanist case study.

Fast growth, rising housing prices

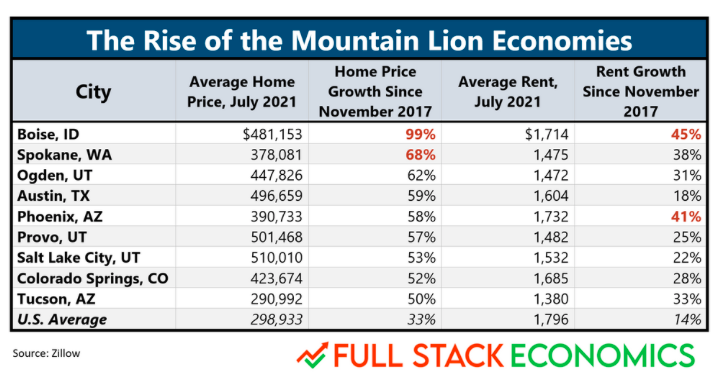

Recently, Boise was placed at the top of a list “mountain lion” cities, by Fullstack Economics, which theorizes that growth in these cities has been fueled by a spillover effect from coastal cities, like San Francisco and Los Angeles. According to Fullstack, the appeal of these cities is rooted in their distinctive natural settings, access to universities, burgeoning tech sectors, and (relatively) affordable housing prices.

However, the affordability edge appears to be on the way out for Boise, which was named as the nation’s most overvalued housing market in a recent study completed by Florida Atlantic University (FAU) using open source data. According to local media, Boise may have reached a tipping point in regards to its affordability in comparison to other other western cities. Boise, was also far from the only mountain lion city on the list, with Austin, Ogden, Provo, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, and Spokane all included in the FAU study’s top ten rankings.

Boise’s real estate industry, however, remains eager to market the city to outsiders. A realty storefront located in the baggage claim of Boise’s airport even makes it possible for new arrivals to begin their property search before even leaving the airport.

The real estate spectacle, most obviously marketed to Californians, runs contrary to efforts by the City of Boise to engage in the development of affordable housing for low-income residents. The City is currently in the process of identifying surplus properties it owns for future affordable housing development, a common strategy in cities where land values have risen to a premium.

Boise officials have also set the goal of building 1,250 new homes and preserving another 1,000 homes affordable to residents earning less than 60% of Area Median Income (AMI) in the next five years. Unfortunately this amount may prove a drop in the bucket relative the Boise’s affordable housing needs; city projections cite 27,000 new housing units (affordable and market rate) as the amount necessary to insert into the market over the next ten years to manage the current housing affordability crisis.

Downtown density and placemaking

For a city most defined by its proximity wide open spaces, notably the nearby Boise Mountains, density has not always been valued in Boise. Yet a visible shift is present in the Downtown core where residential and mixed-use developments are on the rise. According to the Boise Development Tracker, more construction cranes will be dotting the city’s skyline in the near future. Examples of already permitted projects include a 19 story apartment building with retail on ground level, five story residential building with retail space and a public plaza, and a 35-unit condo development near the riverfront. All of these projects — as well as nearly a dozen more — are posed to significantly increase density in Downtown Boise.

Present day Boise wears its history on its sleeve and is heavily engaged in placemaking. Historical markers are present throughout the Downtown core, where the city’s Basque quarter merges cultural and historic preservation through its murals, street signs, and a handful of historic buildings. New construction, however, is rising only steps away, inviting questions as to how the new and old Boise will converge in the future.

Another interesting juxtaposition between Boise’s history and present-day transformation into a dense, modern city is a large nonprofit development called Jack’s Urban Meeting Place (JUMP) Boise, which is located on the west end of Downtown. JUMP Boise was created to honor Jack Simplot, an Idaho entrepreneur who amassed a collection of vintage tractors during his lifetime that he wanted to share with the public in a museum. Instead of building a “typical tractor museum,” the directors of the JUMP Boise nonprofit created a massive campus including an outdoor amphitheater, terraces, rooftop parks, meeting areas, play areas, a five-story slide that can be used in place of stairs, studios that contain audio and visual equipment, as well as 3D printers, industrial kitchens, high-speed WiFi, and performance spaces for music and dance productions. All the JUMP Boise’s spaces are open to the public and intended for public use and collaboration.

In the end [JUMP Boise] is much more than a shared space, it is a vibrant imaginative ecosystem and with community participation it will come to life. We built an inviting space in the heart of downtown so a wide range of people can come together and inhabit this ecosystem, to share thoughts, talents, knowledge, recipes, and ideas. Together we will discover new abilities and interests that are much deeper than we’d ever imagined as we unlock our potential, inspire each other, innovate together, and push the human story forward.

JUMP Boise, 2021

While the pandemic has put classes on pause, currently on display outdoors at JUMP Boise is an installation focused on the idea of what makes a home. A large screen broadcasts photos of people from across Idaho standing on their front porch or near the front door of their home; the same photos are displayed around the outdoor amphitheater accompanied by quotations from the people in the photographs in response to the question of what the word “home” means to them and how the meaning has changed for them in recent years.

JUMP Boise’s distinctive attempt at interactive placemaking might be rivaled by the murals present through the city. In addition to the famous Freak Alley, the murals abound throughout Downtown Boise; some are visible on primary streets, while others are hidden in alley ways are can only be viewed from adjacent buildings. While not all of Downtown Boise’s alleys are activated some are, and in general the alleys feel safe to walk down, even in the evening. The presence of street art does a lot to enliven these spaces.

Walkability and a new pedestrian street

The central core of Boise, ranging from Boise State University south of the river through Downtown to all the way to the residential North End, is largely walkable. Biking, however, might be the best way to explore these areas since streets are flat, well-maintained, and contain many bike lanes. That said, a walkability audit commissioned by the City aptly noted how “pedestrian comfort and business vitality” have been negatively impacted by the design of the Downtown’s street grid around pairs of multiple lane one way streets, which foster a “road racer frame of mind” among drivers.

Implementing a variety of traffic calming measures, including narrowing Downtown streets and redesigning them as two way streets, would go far to improve walkability in Boise. This may prove to be a necessity as the Downtown grows more dense. However, such changes might not be popular with drivers; earlier this year Boise was named as having the “worst rush hour in the country” by a study analyzing congestion and drive times across U.S. metros.

In June of 2020, the City pedestrianized a section of 8th Street in Downtown, an experiment that has proven to be an enormous success with residents, visitors, and local businesses alike. While café permits are currently only registered until April 2022, serious discussion around making the pedestrian street permanent is underway. With over 21,000 students currently attending Boise State University, a night out in Downtown can be reminiscent of a lively college town, and the 8th Street businesses clearly benefit from patronage by students.

It also helps that the North End neighborhood laying just beyond the Capitol Building was designed for walkability. Its leafy streets contain a mix of single family residences, backyard cottages, apartment buildings, quadplexes, and courtyard bungalows. The North End also includes its own small shopping district, Hyde Park, centered on N 13th Street. The presence of the neighborhood feeds into the walkability of Downtown Boise, creating a cohesive urban fabric. As whole, the Downtown and surrounding neighborhoods have good sidewalk infrastructure and pedestrian crossings, even in places where roads may be wide and frequented by fast-paced vehicle traffic.

Bicycles, everywhere; transit, not so much

Bicycles are a visible presence all over Boise, at least during the times of year when the streets are free of snow and ice. Mountain bikes are a popular choice, likely because the city has mountain bike trails that extend north from the city limits into the foothills of the Boise Mountains.

Boise also has 25 miles of riverfront greenbelt that connect 12 public parks. The trails are very popular with pedestrians, cyclists, and a growing number of e-scooter users. After Boise’s Greenbike bike share program shuttered in 2020, e-scooter companies moved in in force. E-scooters are a visible presence around the Downtown and in the riverfront parks; they can make for an interesting way for visitors to explore the these natural areas as well as the Boise State University campus.

Cyclist safety, however, continues to be a topic of concern. Local nonprofits like the Boise Bike Project aim to increase cyclist safety through educational programming and advocacy for safer streets.

A quick note on transit: Boise and the surrounding Treasure Valley have a local transit authority offering bus service; however, public transportation is generally not considered to be a viable choice for many people because of infrequent service and slow travel times. COMPASS, the local community planning association, is engaged in longterm planning for expanding and improving public transportation in the region, but it appears to be a long way off from making significant progress. Still, with congestion a major regional concern and a rapidly growing population, the City of Boise would be well served to invest its public transportation, especially since the City has adopted a climate action plan which calls for Boise to be carbon neutral by 2050.

This article was edited to remove data from the 2020 U.S. Census that was taken down from the census website.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.