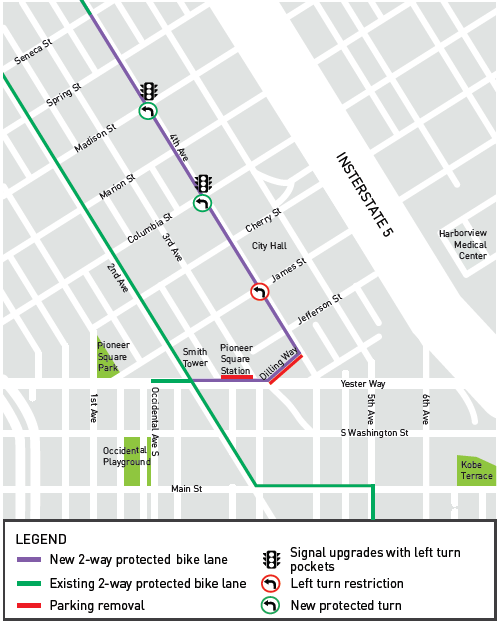

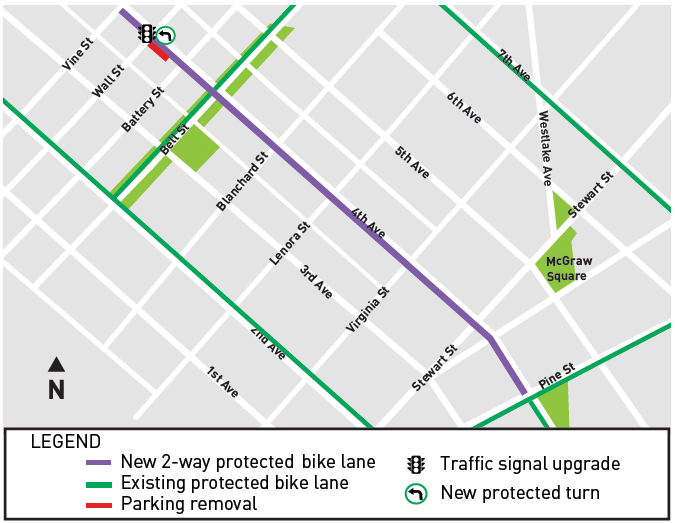

This past weekend, Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) crews marked out a protected bike lane on 4th Avenue in downtown Seattle, extending the existing bike lane from Marion Street south to Dilling Way, just south of the King County Courthouse. Now a two-way bike lane extends from Pine Street all the way to Yesler and 2nd Avenue where riders can connect northbound back through downtown or south to the International District. The new extension is noticeably more narrow than other two-way bike lanes in the city, including 2nd Avenue. But the connection will be invaluable to people who haven’t had a separated facility in the area, particularly when heading south.

In what will be a counterintuitive move for many riders, the bike lane takes a detour away from 4th Avenue at Dilling Way, the roadway on the south end of City Hall Park. That segment of the protected bike lane (PBL) is temporarily closed with the rest of the park, with a temporary detour set up in the alleyway between the King County Courthouse and the park.

On the east side of 3rd Avenue, people on bikes are directed onto the sidewalk, which has been repaired in that area with wide custom curb cuts added. A slip lane from northbound 3rd Avenue onto Yesler Way has been closed, a benefit to all people walking, biking or rolling through that intersection.

North of Pine Street, the bike lane is still just technically northbound only to Bell Street, with an extension to Vine Street and conversion to two-way planned there in the coming weeks. But plenty of people are already using the bike lane to head southbound as well.

The addition of a second north-south protected bike route has been a long time coming and provides a very useful connection. The 4th Avenue facility is closer to amenities on the east side of downtown than the 2nd Avenue PBL, which is located down a steep slope in many sections, making detours to use 2nd Avenue inconvenient for trips to destinations higher up the hill. The project was once planned to be completed in 2017, but a comprehensive review of downtown street space, compelled most urgently by the closure of the Alaskan Way viaduct happening in early 2019, delayed it.

That review, called the One Center City planning process, included a long list of downtown stakeholders and agency representatives. At the end of the process, the recommendations were presented as part of a package that included a new northbound transit pathway on 5th and 6th Avenues and a protected bike lane on 4th Avenue. When members of the One Center City advisory group left what was essentially their last substantive meeting in late summer 2017, the bike lane was happening.

Then Jenny Durkan took office. Despite the fact that the models from One Center City showed that transit times would improve with the added bus lanes even with the removal of a fairly superfluous left-hand lane on 4th Avenue, the City used the specter of buses getting delayed by a traffic apocalypse (which didn’t end up materializing) to put the lane on ice. Rather than seen as part of the mobility solution with the viaduct closed, bike lanes were framed an impediment for which the city wasn’t ready.

Even now, the full connection south of Yesler Way to S Main Street was seen as not doable in terms of projected impact on buses in the corridor, and so the circuitous detour onto Dilling Way was proposed instead. With the number of buses heading downtown reduced as additional light rail stations open, the full connection on 4th Avenue S will be revisited.

Another key reason the 4th Avenue protected bike lane was included in the package was safety, something the Durkan administration has demonstrated further disregard for in its actions since. Adding a PBL was expected to yield an 18% reduction in bicycle related crashes and contribute to a 10% reduction in pedestrian collisions through added protected signals. With the added lane this weekend, turn restrictions went up at James Street, allowing people walking and rolling through the crosswalk to not have to worry about turning vehicles.

Now those safety impacts can finally be realized as people choosing to bike downtown no longer have only one choice for a separated facility to head north and south. Progress to build the basic bike network has been slow, but we owe a debt to the advocates pushing to make sure promises are fulfilled, and to the City for following through.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.