The four members of the Washington State Redistricting Committee submitted their first draft of maps this week. At this stage the four maps — two Democrat and two Republican appointees — differ a lot, but it does appear like some districts will become more favorable for Democrats. This is a product of Democratic districts generally growing faster than the more rural Republican districts.

Broadly speaking, Washington’s 49 state legislative districts will tighten around metropolitan areas to reflect the greater population growth within them. Some of the fastest growing areas include Seattle, Vancouver, and the Tri-Cities. The maps take some very different paths in the requisite population shifting to get each district within range of the new district population average of 157,251, which reflects the 14.6% growth in Washington State since the last census in 2010. How redistricting plays out will have huge implications for controlling the state legislature, particularly in swing districts where a nudge in one direction could make a big difference. A stronger progressive tilt in a district could also improve prospects for progressive challengers against moderate Democratic legislators.

In the last two cycles, Democrats have had a firm grip on power with the Washington State Senate split 28-21 and the State House split 57-41. Democrats made big gains in 2018 and defended their new seats in 2020, swapping losses in Legislative District 19 for a Senate seat pickup in the 28th courtesy of T’wina Nobles and a House seat pickup in the 42nd via Alicia Rule.

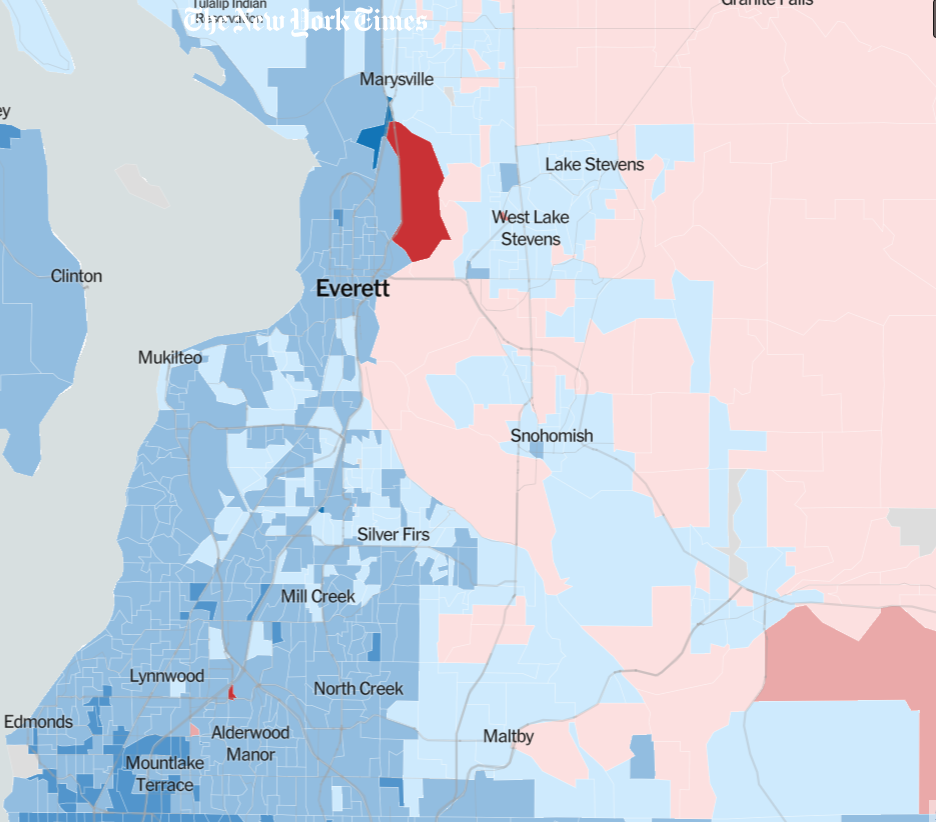

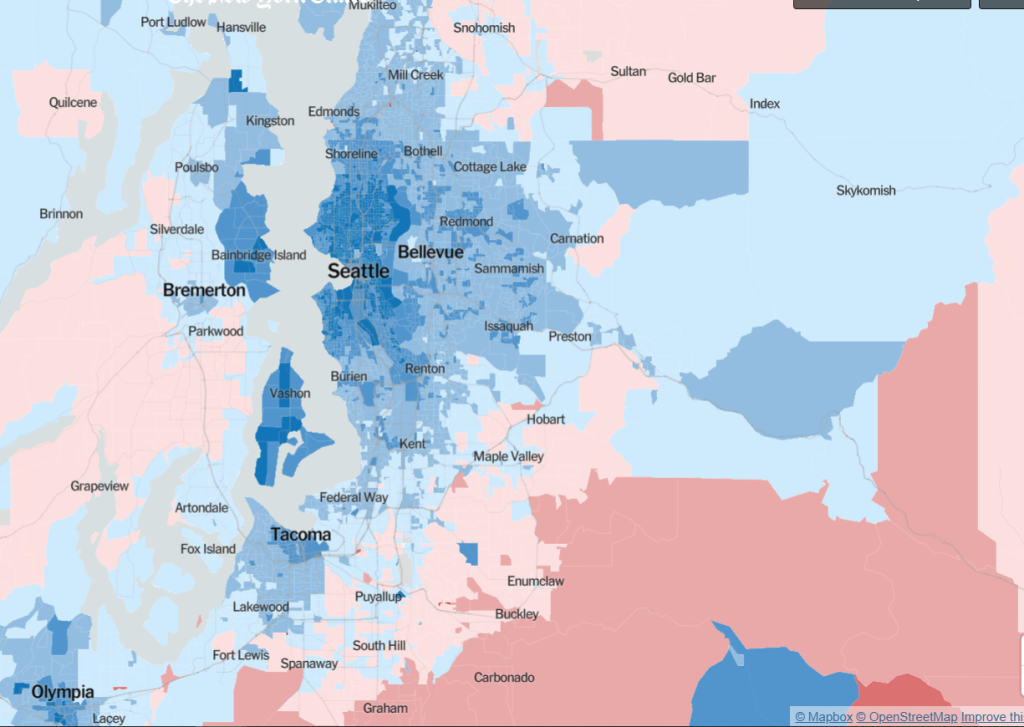

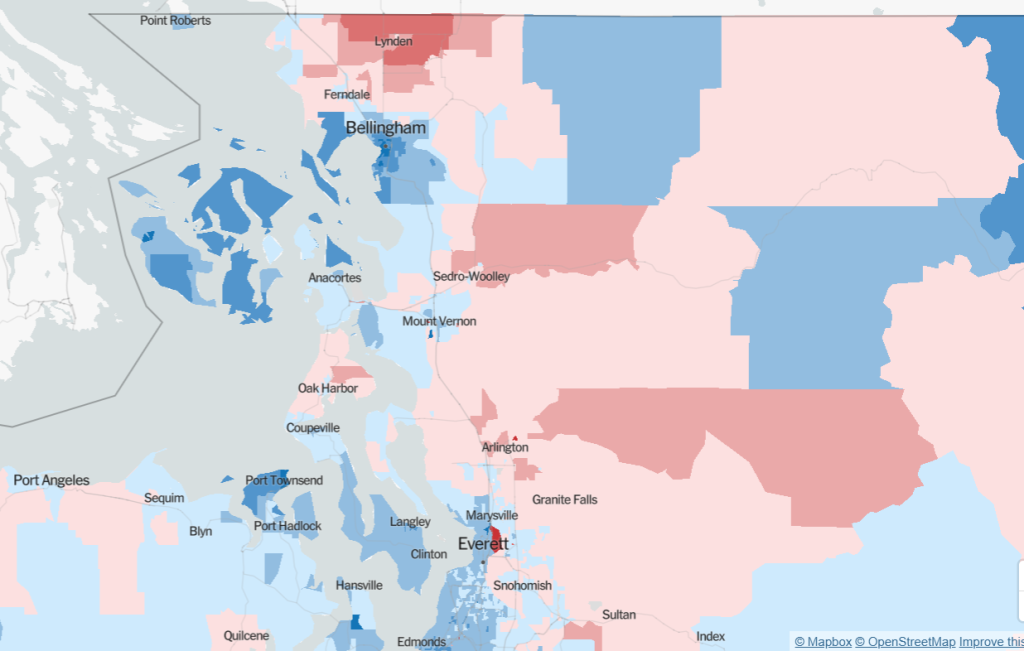

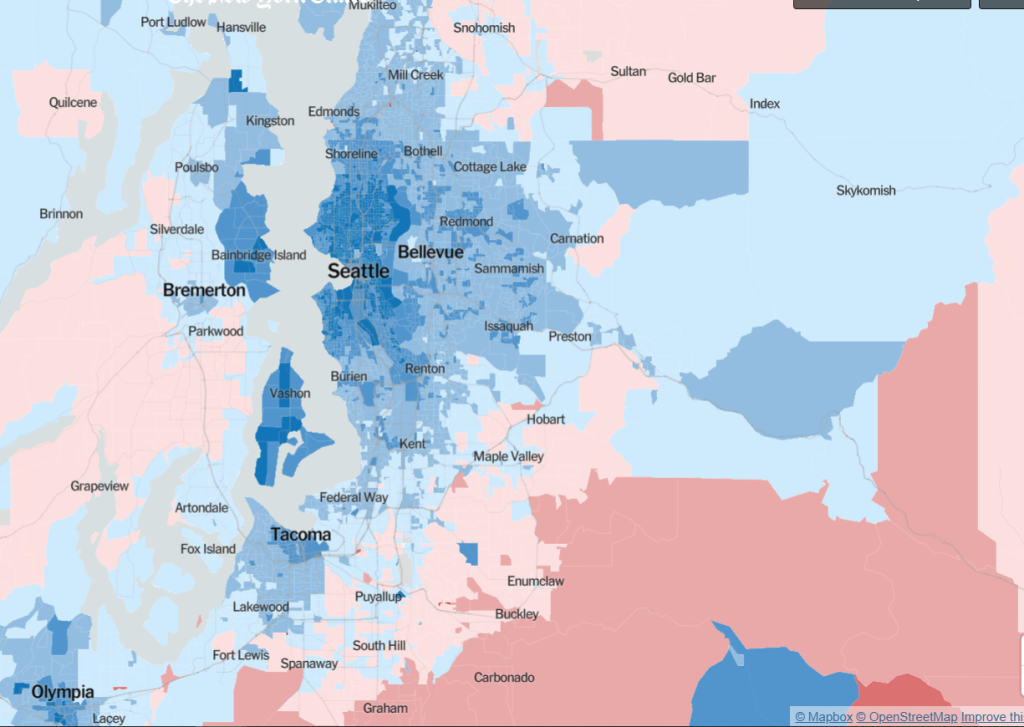

The overall pattern is fairly consistent across the state and country. Urban areas lean heavily Democrat, while rural areas lean Republican. The biggest exceptions to that pattern are tribal lands and college towns, which both also break for Democrats and interrupt the sea of red between major cities. Suburbs can be a bit of a mixed bag, but in Western Washington they tend to break Democrat — save for some parts of the exurban fringe — particularly following the White Nationalist drift of the party in the Trump era.

While we could delve into all four commissions maps, let’s ignore the Republican maps for now to make this simpler and spare ourselves some groans. (Here are the links for Paul Graves’ map and Joe Fain’s map if you’re curious to see the Republicans’ proposals.) That leaves us with a map from April Sims, Secretary Treasurer of the Washington State Labor Council and the first women of color to serve on the commission, and a map from Brady Piñero Walkinshaw, CEO of Grist and the first Latino to serve on the commission.

Here’s how the maps are shaping up in key swing districts.

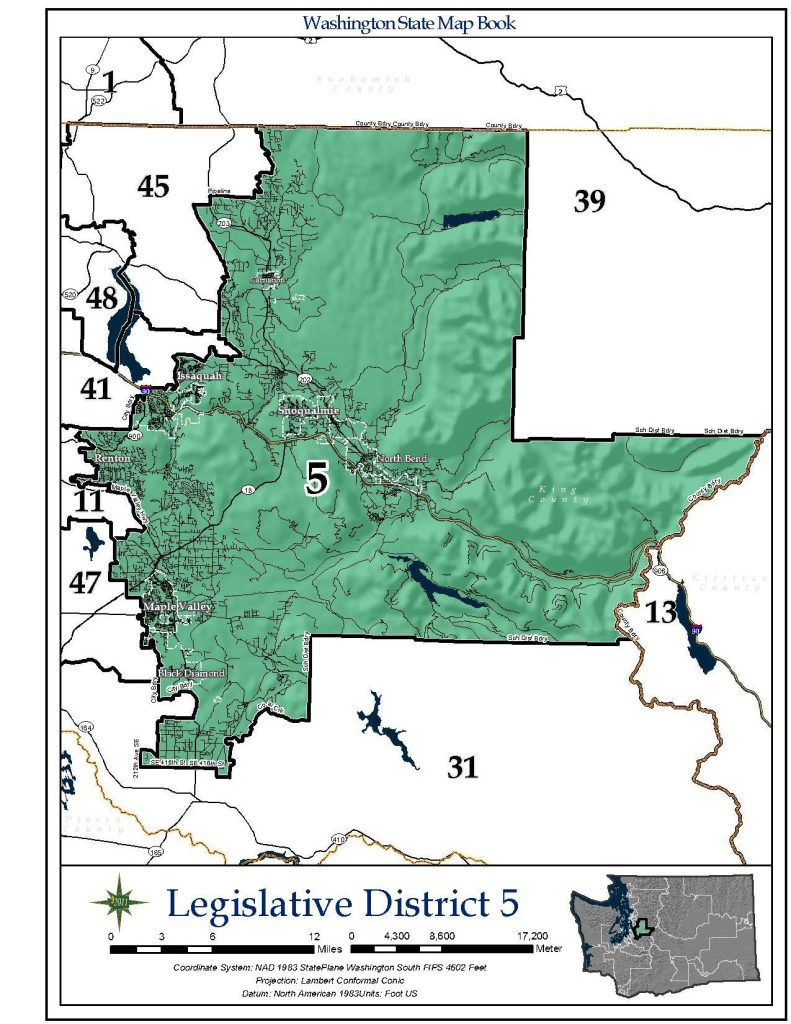

5th District

The 5th district has been one of Washington’s most contested swing districts. It was Republican controlled until the 2012 election, when Democrat Mark Mullet defeated Republican Brad Toft by a razor-thin margin. Mullet proved to be so moderate that he upset the progressive wing of the party with plethora of anti-union, corporate-friendly, and climate-delaying votes and stances. Ingrid Anderson — a nurse with strong union backing — challenged Mullet from the left in 2020, but he survived a recount to hold onto the seat.

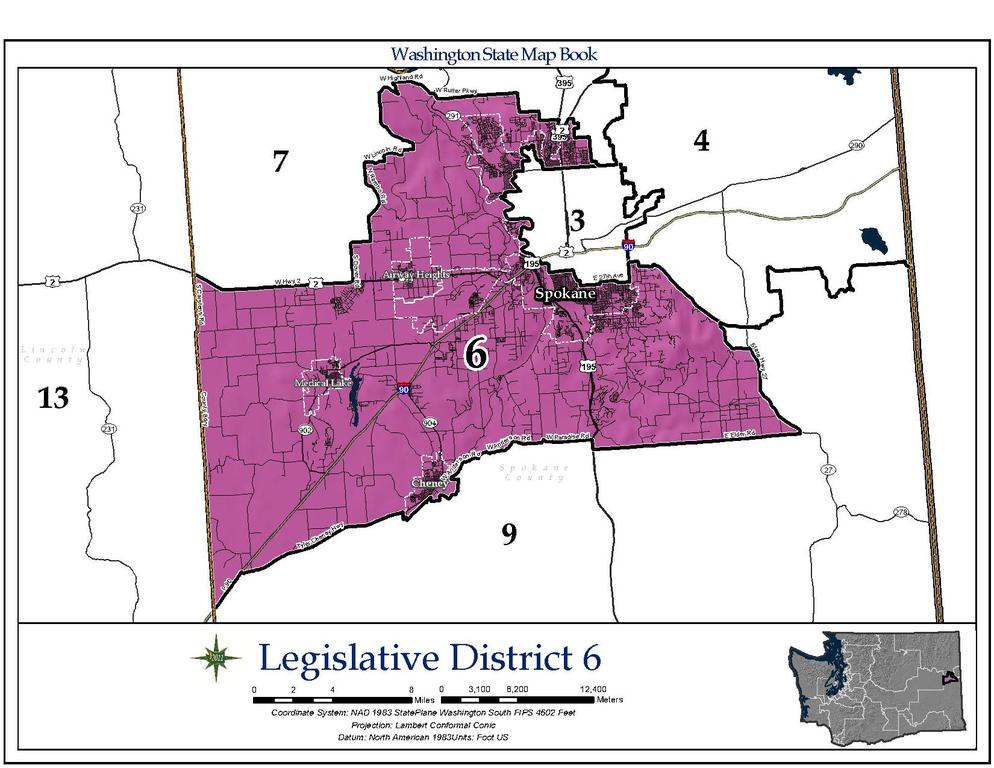

The 5th Legislative District covers eastern King County. (Secretary of State)

King County overwhelming favored Biden and Democrats in the 2020 election, but Republicans did have a pocket of support in the SR-169 corridor. (Credit: New York Times)

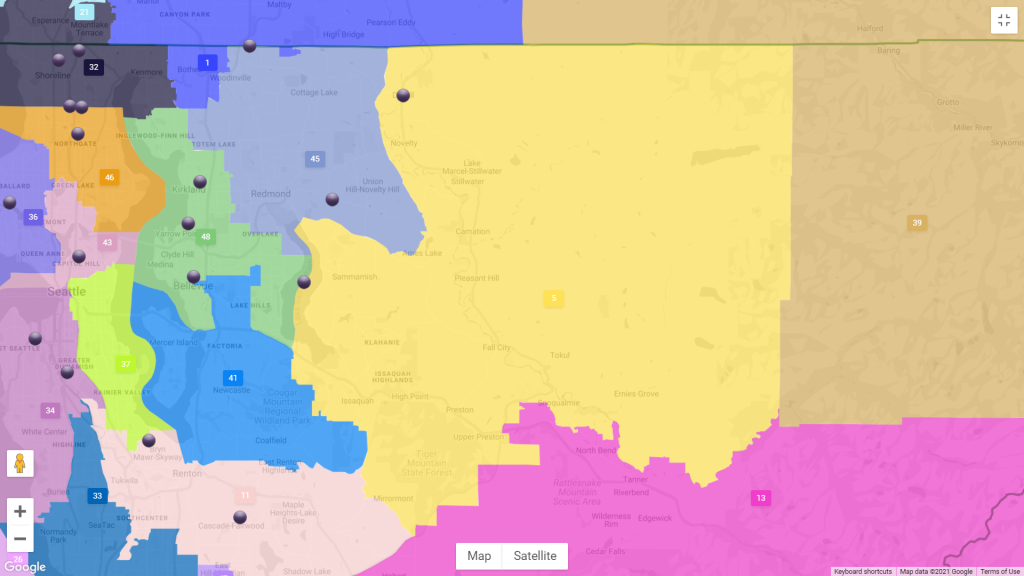

Brady Walkinshaw’s proposed 5th District is in yellow. (Credit: Washington Redistricting Commission)

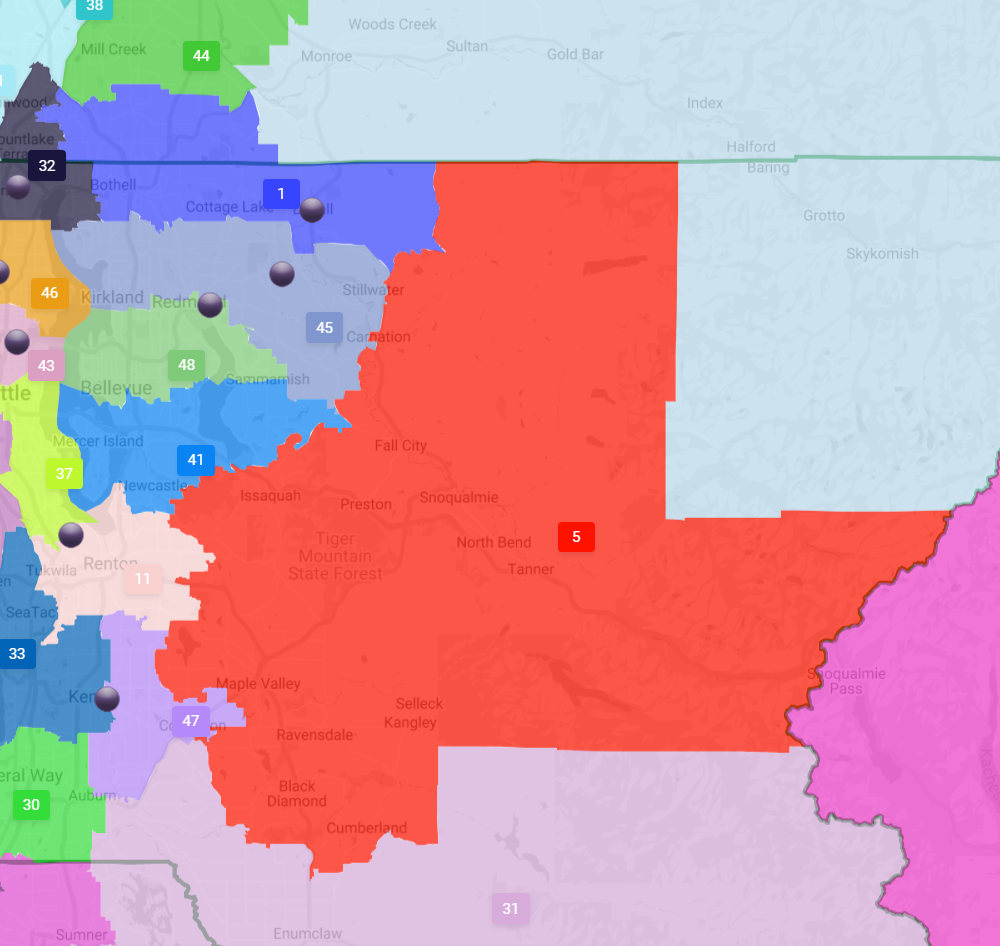

April Sims’ proposal for the 5th District is in red. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

At first glance, Sims’ map may actually make the district a little more conservative by dropping Renton, which is solid Democratic territory, and adding more unincorporated areas around Black Diamond. Walkinshaw’s map looks a bit more favorable to Democrats by adding much of Sammamish and more of Issaquah to the district, while dropping Black Diamond, Ravensdale, and part of Maple Valley.

6th District

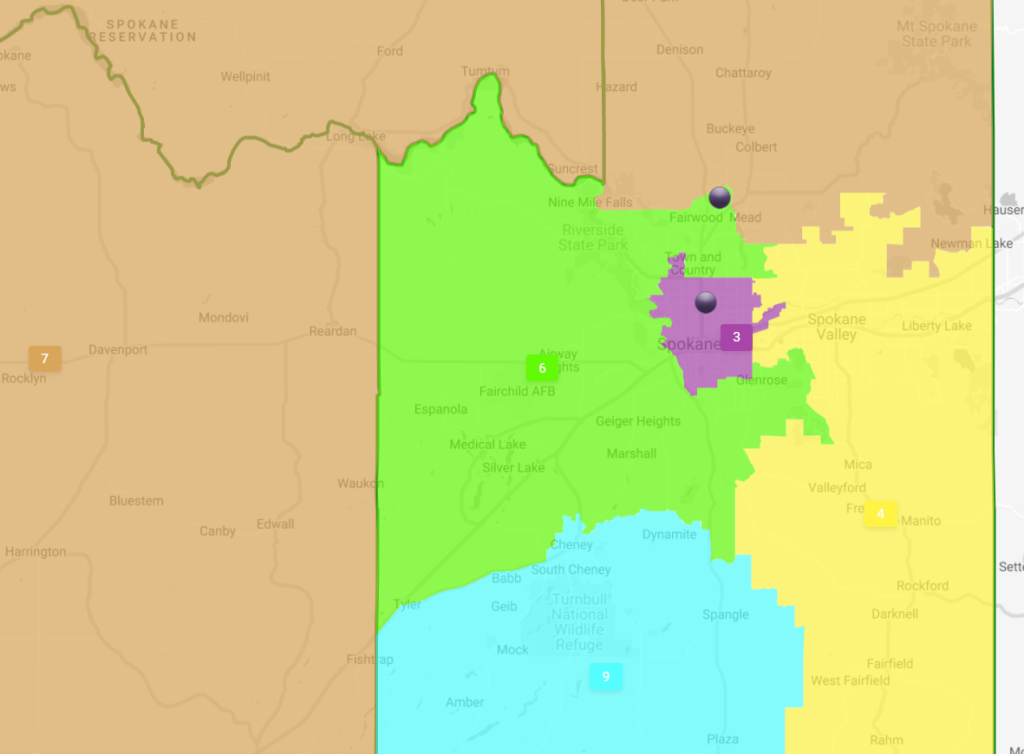

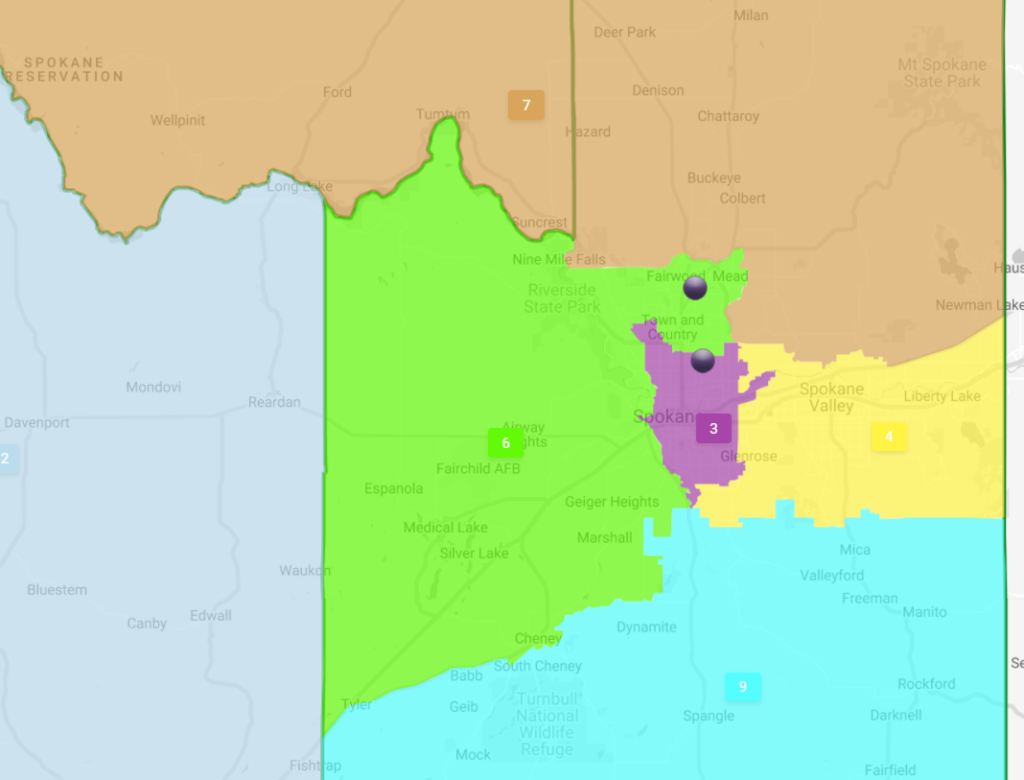

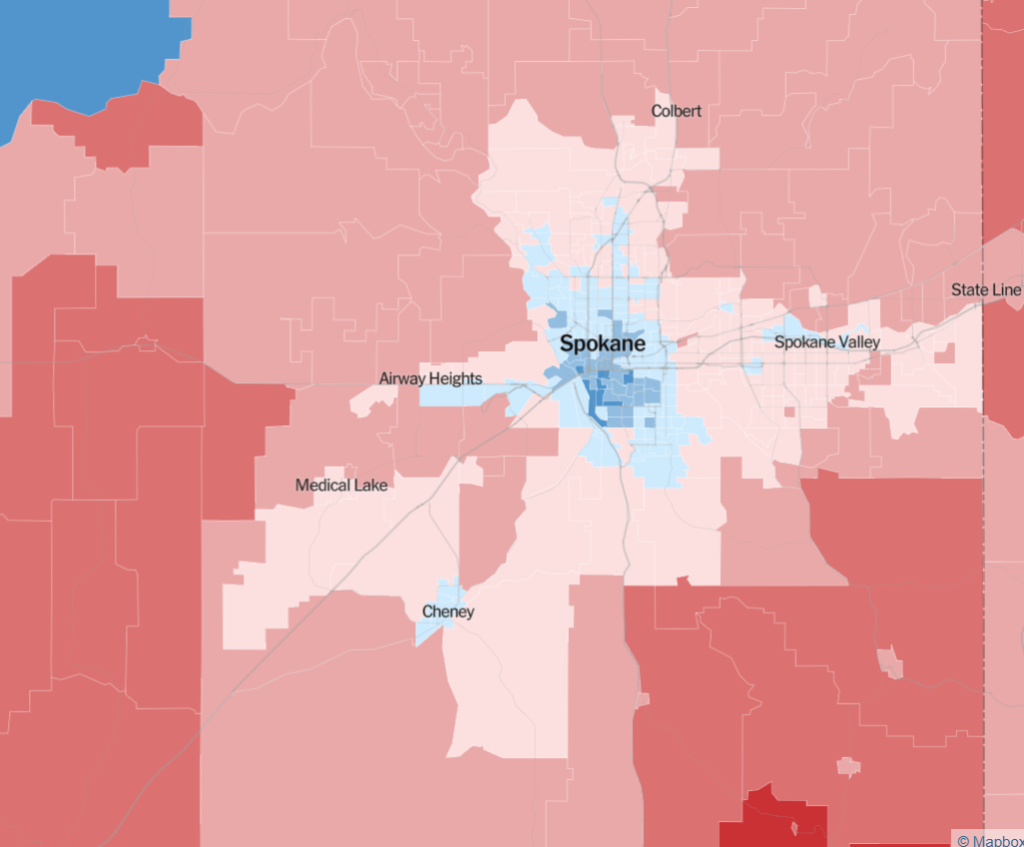

Rep. Mike Volz (R-Spokane) held off a challenge from Zach Zappone (D-Spokane) in 2020 by just 3.9 points. A more favorable map could put the 6th in play for strong Democratic candidates. No major changes are proposed in either Democratic map, but adding just enough of the Spokane core could make the difference — Spokane’s 3rd District provides Democrats their only legislative seats in Eastern Washington. At first glance, the Walkinshaw map would appear less favorable by ceding Democrat-friendly territory in south Spokane. Sims’ map seems to add a little in North Spokane suburbs which may do just enough to help somebody like Zappone pull off the upset.

Sims’ proposed 6th Legislative District (in green) includes more of Spokane. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

Walkinshaw’s proposed 6th District (in green) drops the Moran Prairie area. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

The 2020 presidential results map shows Democrats had strong support within Spokane, but it fades fast farther out from the center city save for a patch of support in Cheney. (Credit: New York Times)

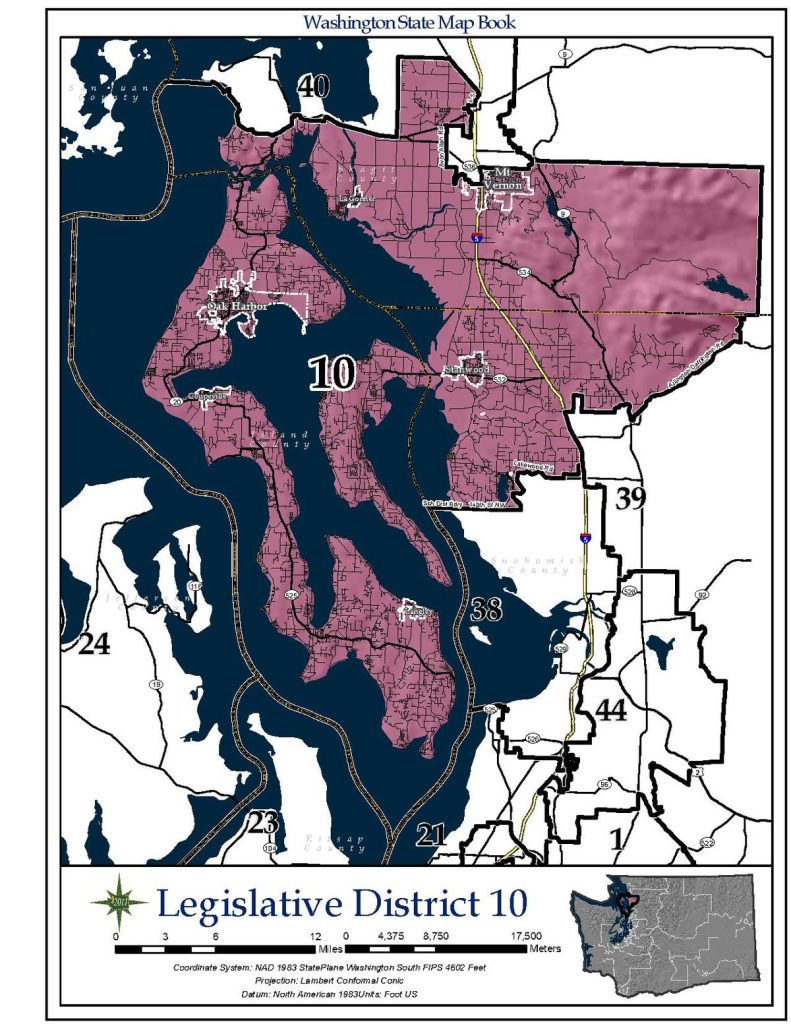

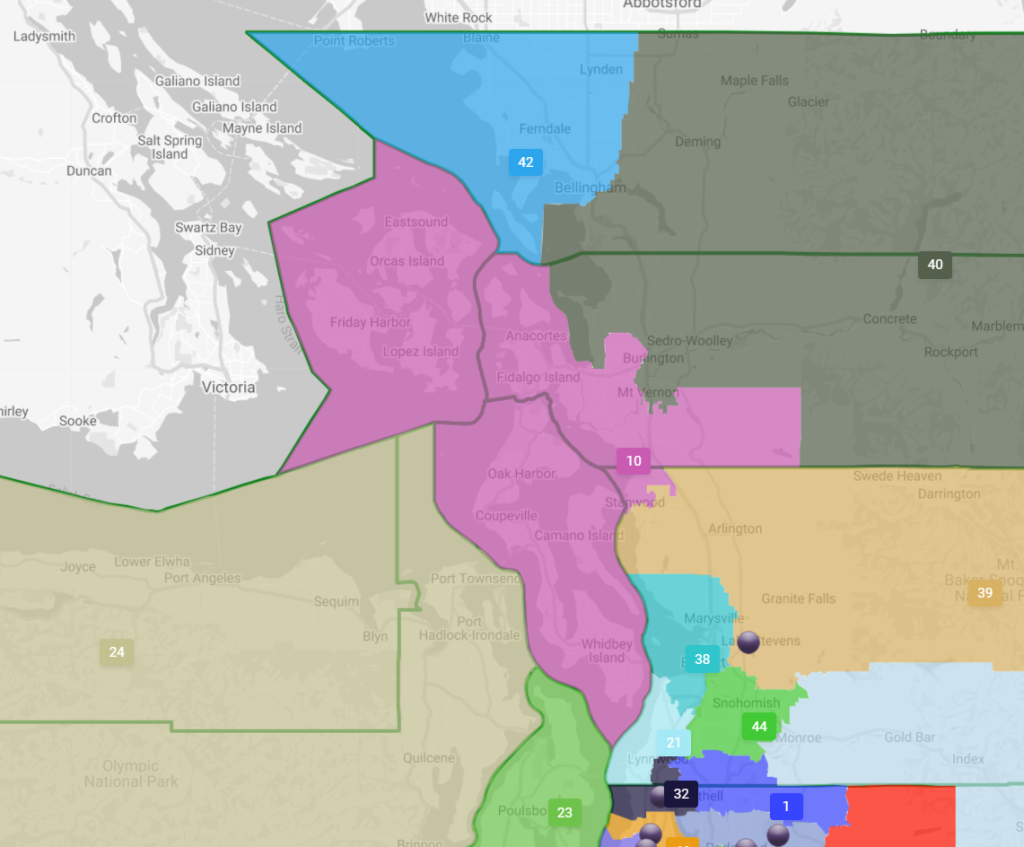

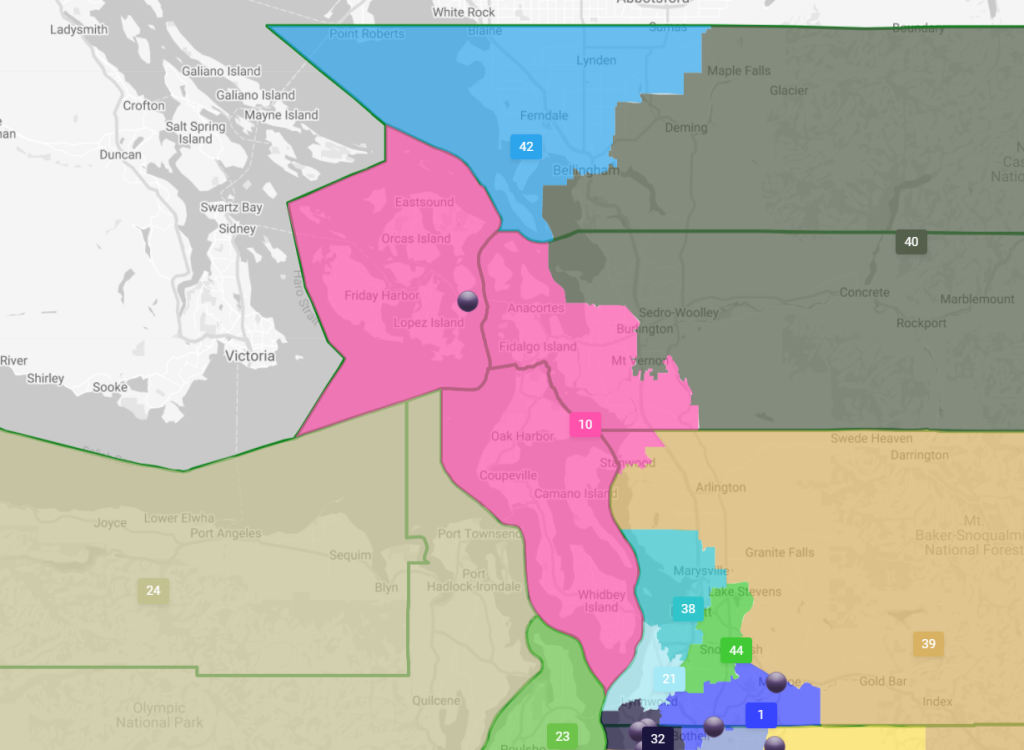

10th District

The 10th District ended up being a heartbreaker for Democrats in 2020. Democrats Helen Price Johnson and Angie Homola appeared in line for a win on election night, but both fell behind as late returns trended Republican in the district.

The LD10 that Walkinshaw has drawn appears to be a solidly Democratic district. The district adds the San Juan Islands to make it even more archipelagic, with Whidbey and Camano islands in its borders. The San Juans are heavily Democrat and registered the strongest support of any county for the carbon fee ballot measure in 2018 — though the county’s population is a modest 17,788. Sims also opted to add the San Juans to LD10, and her map is very similar. One difference is it juts a little farther east into Skagit County, but probably not enough to make much of a difference.

Giving up San Juan Islands will make the 40th Legislative District less of a Democratic stronghold, but it would probably still be solidly Democratic given how strong the tilt was in recent elections.

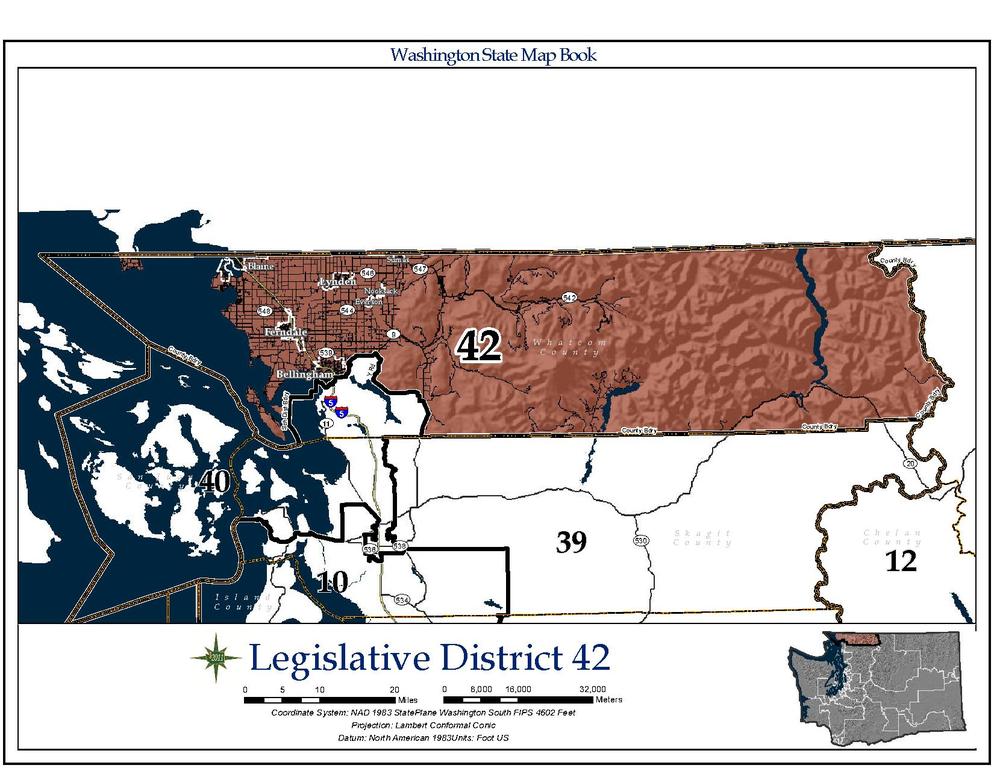

42nd District

Walkinshaw and Sims have continued to split Bellingham between the 40th and 42nd (see above), but the 40th losing the San Juan Islands and giving up too much of Bellingham could boomerang this increasingly Democratic district to the Republicans. Democrats have steadily been doing better in the 42nd. Rep. Sharon Shewmake (D-Bellingham) won a seat in 2018 and defended it in 2020, while Alicia Rule (D-Blaine) knocked out a three-term Republican incumbent in 2020.

Both Sims and Walkinshaw take a similar tactic carving out a triangular district by giving away the rural interior of Whatcom County to the 40th. Lynden is the most solidly Republican area in the county based on 2020 results and it would stay in the 42nd under both maps, suggesting the district may remain a swing district. What’s harder to eyeball is if the 40th has lost enough Democratic-leaning precincts in these maps to become more of a coinflip district itself. It could be all three become Democratic leaners instead of having the 40th a Democratic stronghold and the other two swing districts.

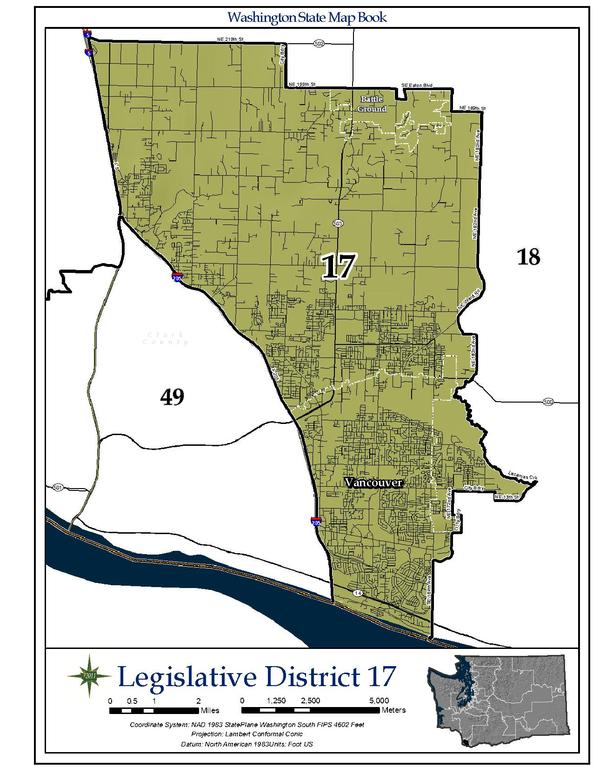

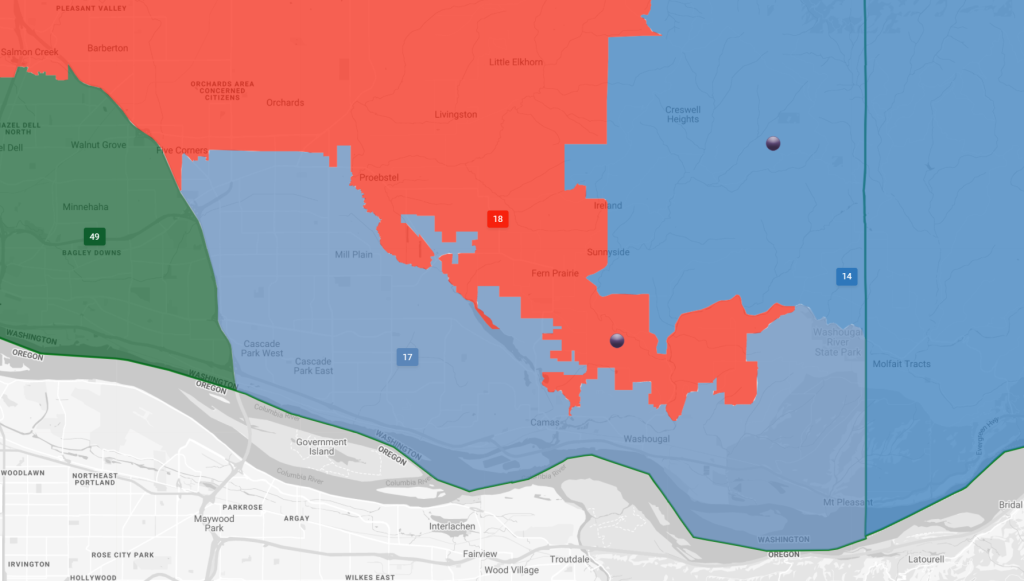

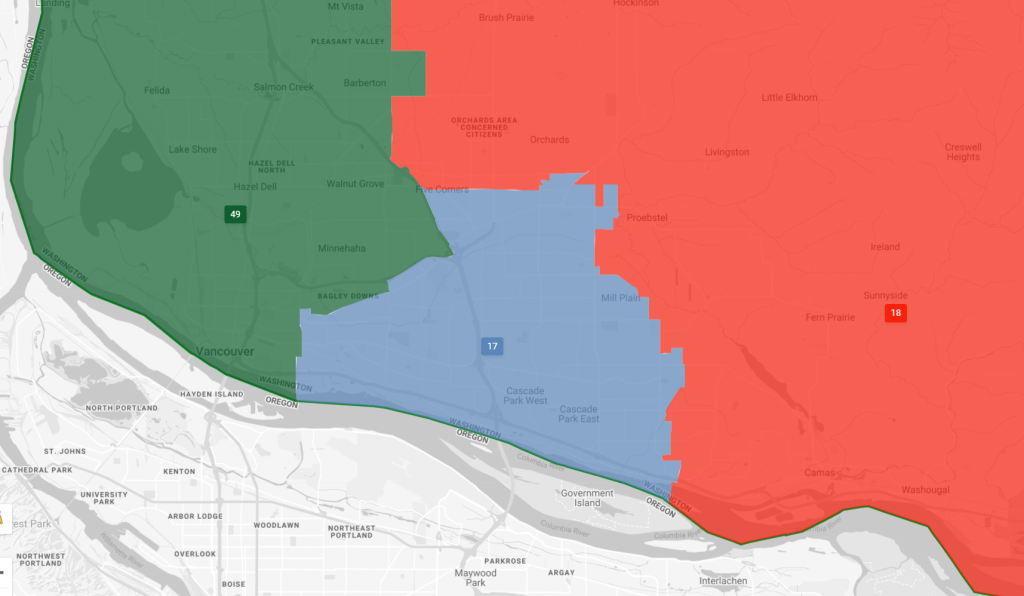

17th District

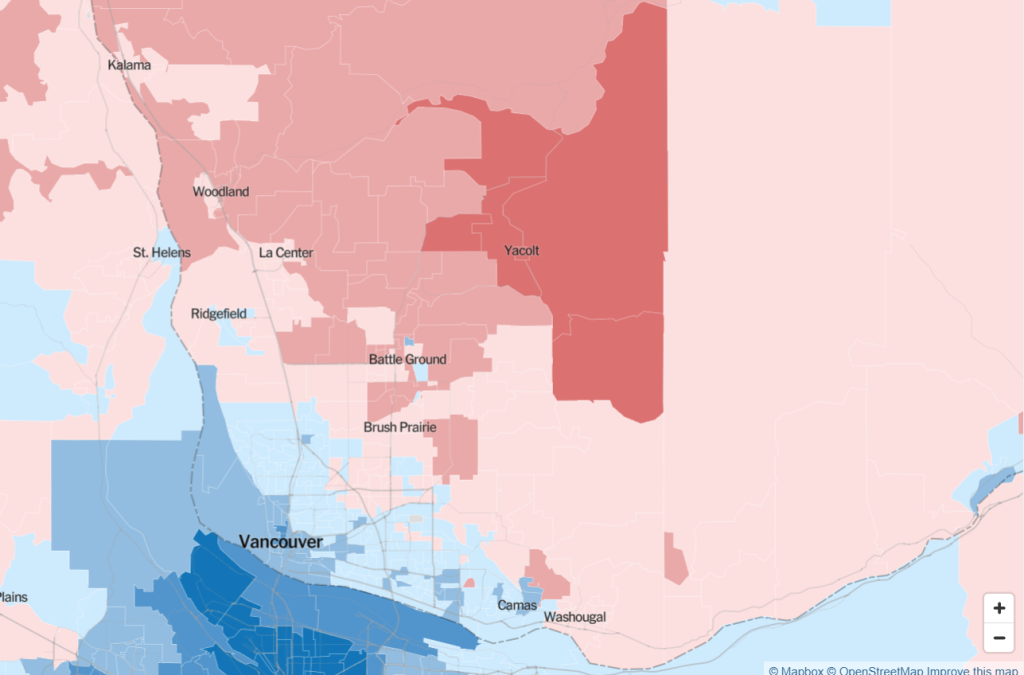

Democrats attempted to contest the 17th District in 2020, but Republicans defended their turf in a district that includes part of Vancouver and farther afield Portland exurbs. Maps from the Democratic commissioners would pull the 17th closer to the Columbia River and farther east, jettisoning more firmly Republican northern exurbs. This likely would make it considerably more favorable for Democrats.

Sims’ 17th Legislative District proposal hugs the Columbia valley and drops northern exurbs. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

Walkinshaw’s 17th District proposal. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

Democratic support in Clark County dissipates farther from the Vancouver core as the 2020 presidential results show. (Credit: New York Times)

Though they draw different shapes, Sims and Walkinshaw seem to get a similar effect for the 17th, with Camas and more of Vancouver joining the districting, adding more Democrat-friendly territory. Meanwhile, the northern suburbs joining the 18th District would appear this to make this a safer Republican seat.

25th District

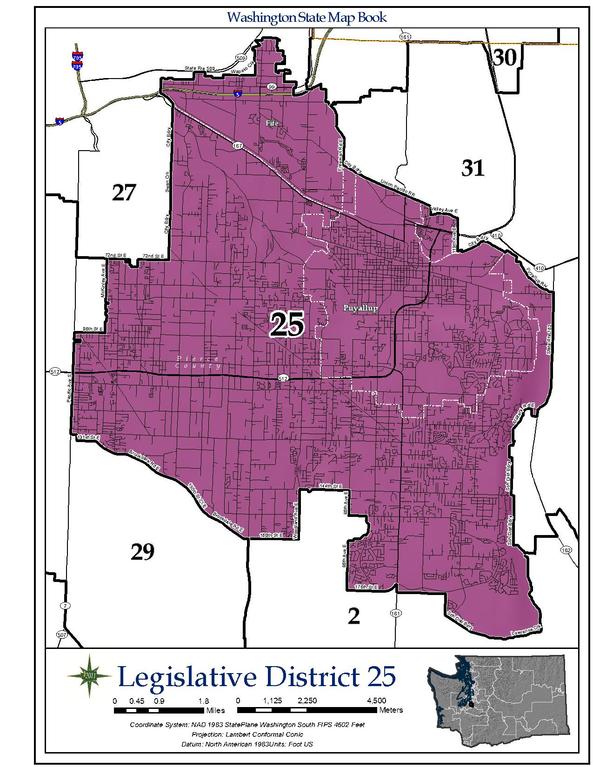

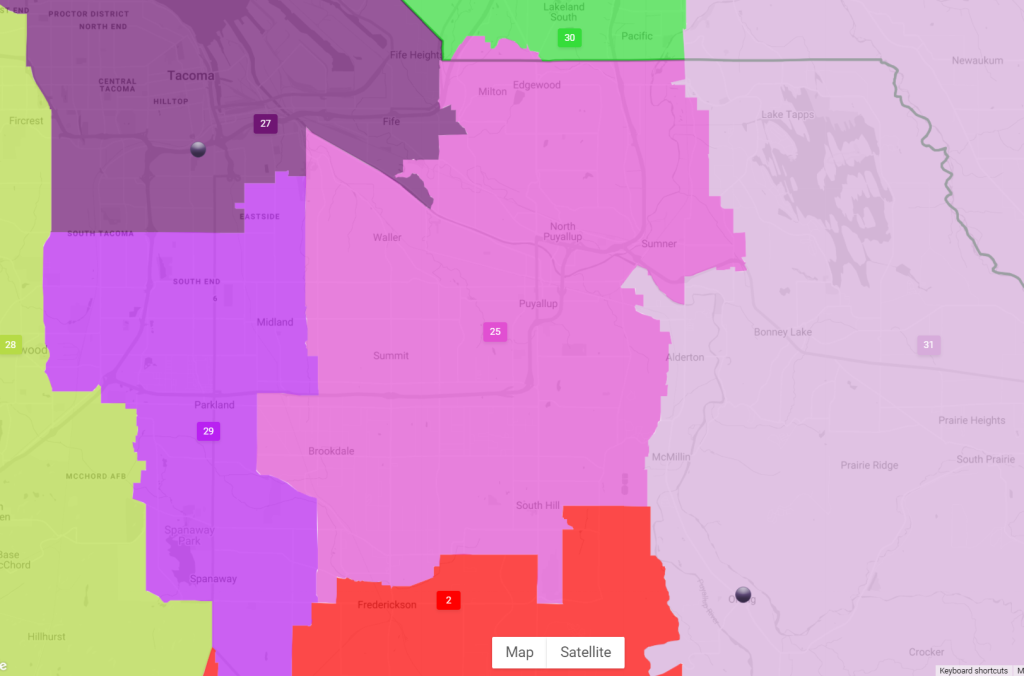

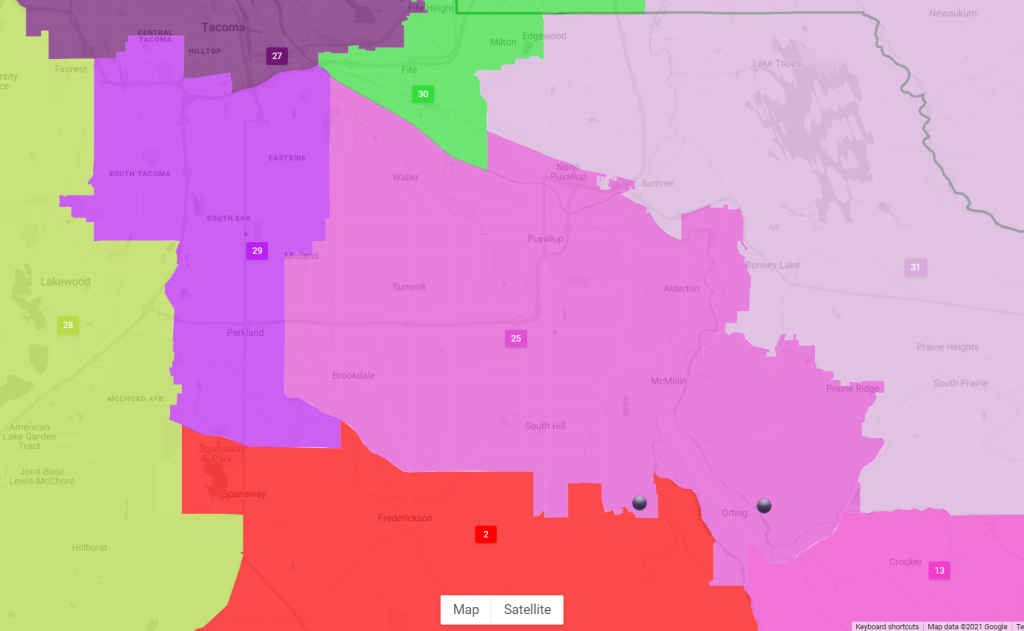

After their 2018 sweep, Democrats controlled every district in the King County suburbs, but Pierce County has been less fertile ground for them. Republicans continued to cling to the 25th District, but the new map could make that harder. In both iterations it continues to be centered around Puyallup, which leans Democratic, but much of the unincorporated sprawl around it is pretty solidly Republican. Sims’ map shifts the district northward away from this Republican-stronghold sprawl, whereas Walkinshaw picks up more sprawl to the east, which likely would have the opposite effect and make the district safer for Republicans. State Senator Chris Gildon (R-Puyallup) won by 7.8 points in 2020 as did Rep. Kelly Chambers (R-Puyallup) by a similar margin, but Democrat Brian Duthie came within five points of besting Rep. Cydney Jacobsen (R-Puyallup), suggesting Democrats could be competitive here, especially with a more favorable map.

Today’s 25th Legislative District. (Washington State)

Sims’ LD25 proposal is in light purple. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

Walkinshaw’s LD25 proposal is in light purple. (Washington Redistricting Commission)

King County overwhelming favored Biden and Democrats in the 2020 election, but Republicans did have a pocket of support in the SR-169 corridor. (Credit: New York Times)

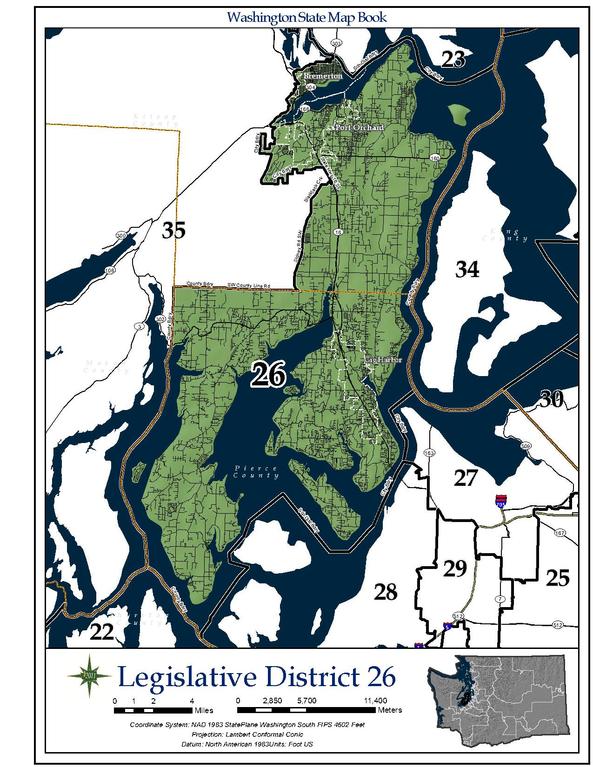

26th District

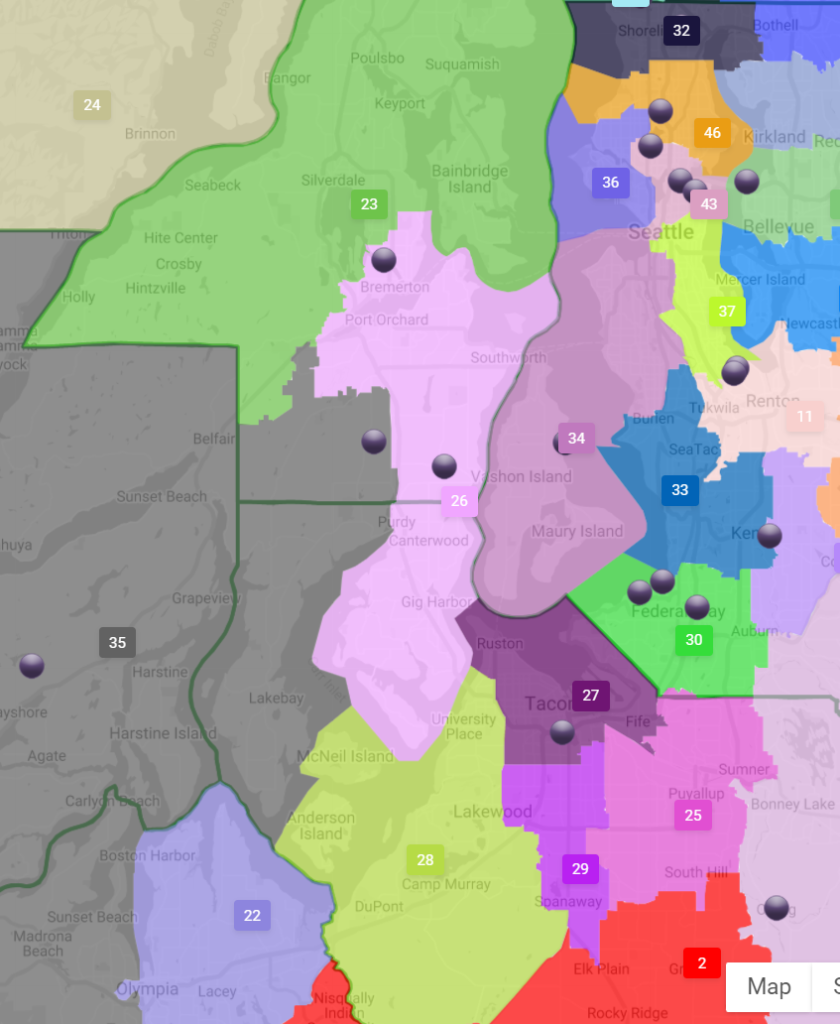

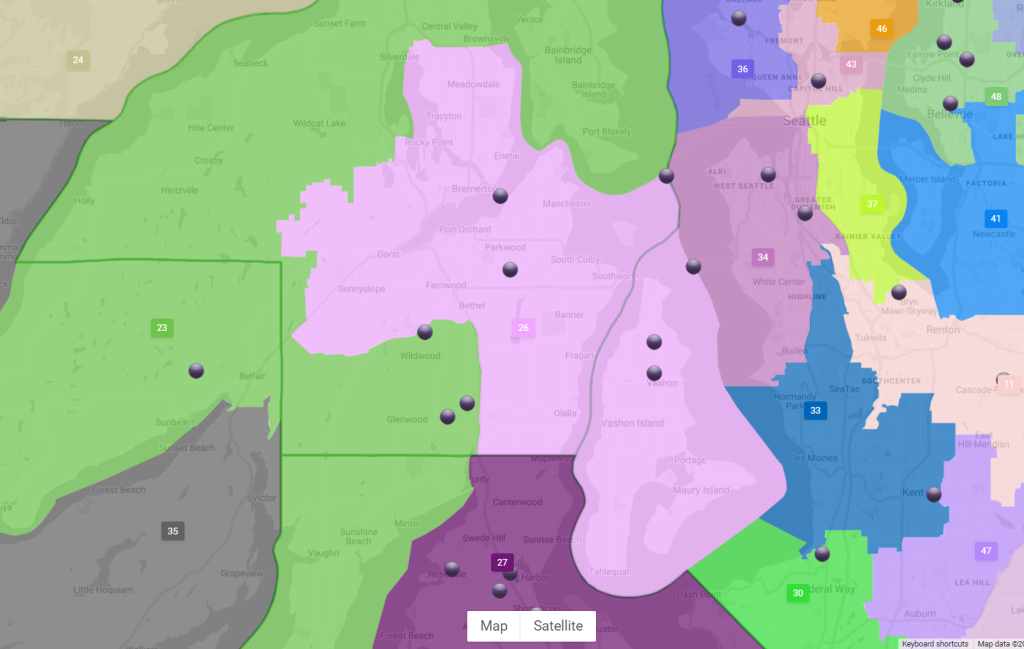

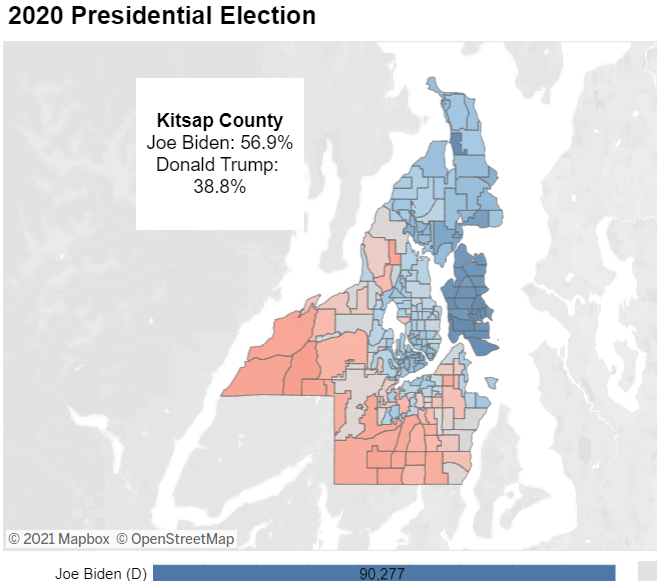

State Senator Emily Randall (D-Bremerton) pulled off a stunning upset in 2018 in what would had been considered a safe Republican seat. In 2020, Democratic candidates weren’t able to replicate her success and Republicans held onto to both seats in the state house. Democrat Carrie Hesch came within six points of unseating Rep. Jesse Young (R-Gig Harbor). Kitsap County gave President Joe Biden 57% of the vote in 2020, suggesting a leftward drift overall, but the boundaries of the 26th within the county had previously given Republicans the edge, but that may no longer be the case going forward.

Both Sims and Walkinshaw’s maps appear more favorable to Democrats, albeit with very different shapes. Sims largely keeps the existing shape but adding more of Bremerton will likely be enough to swing the district. Walkinshaw meanwhile shifts the borders farther east and north, picking up Vashon Island, Maury Island, and all of Bremerton. This would give the district a decided Democratic lean and incidentally it would district out Rep. Young, who’s from Gig Harbor, which is in the southern tip of today’s district. Rep. Michelle Caldier (R-Port Orchard) would still reside within the district and her 10-point win in 2020 suggests she may remain formidable even if the map leans slightly blue.

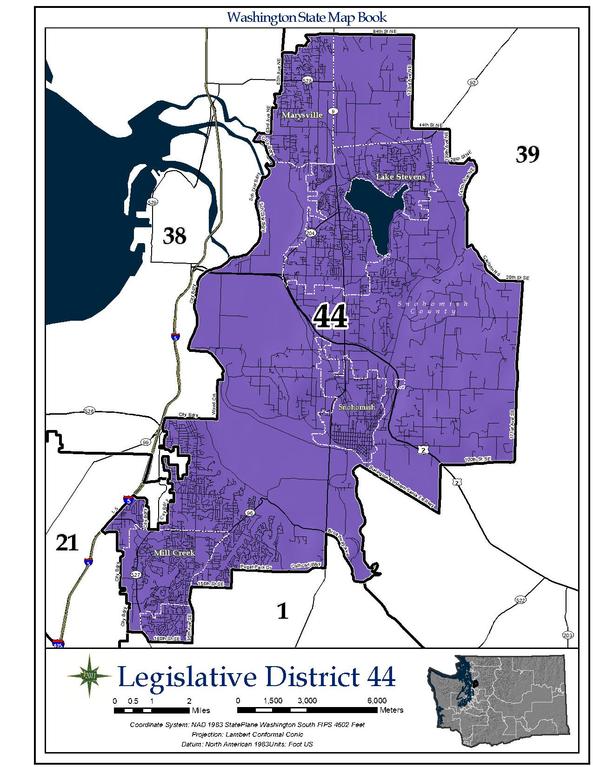

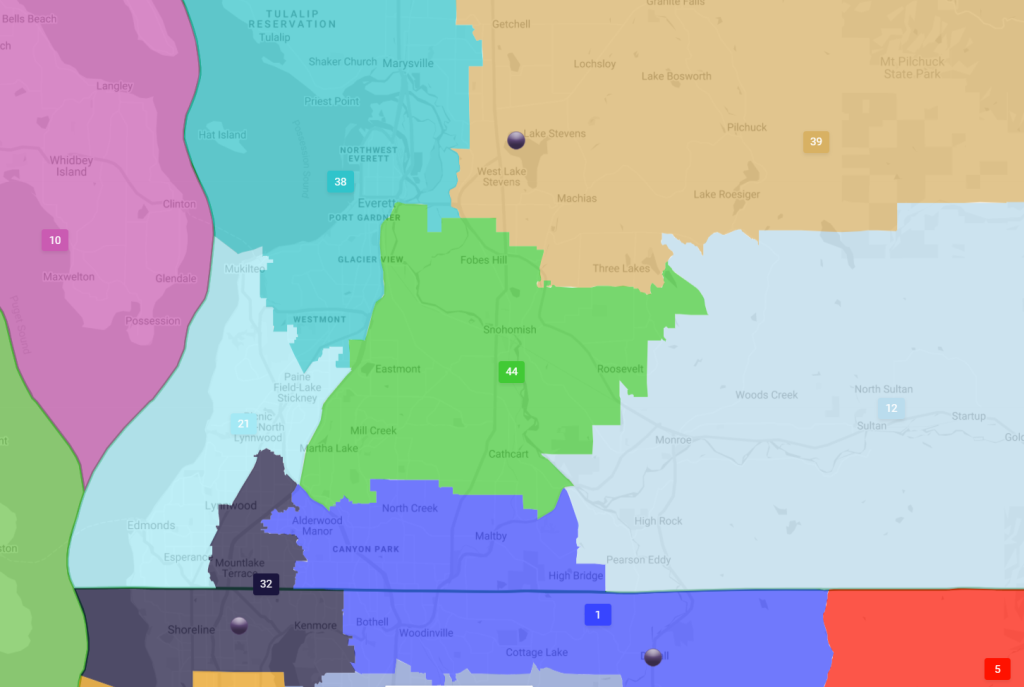

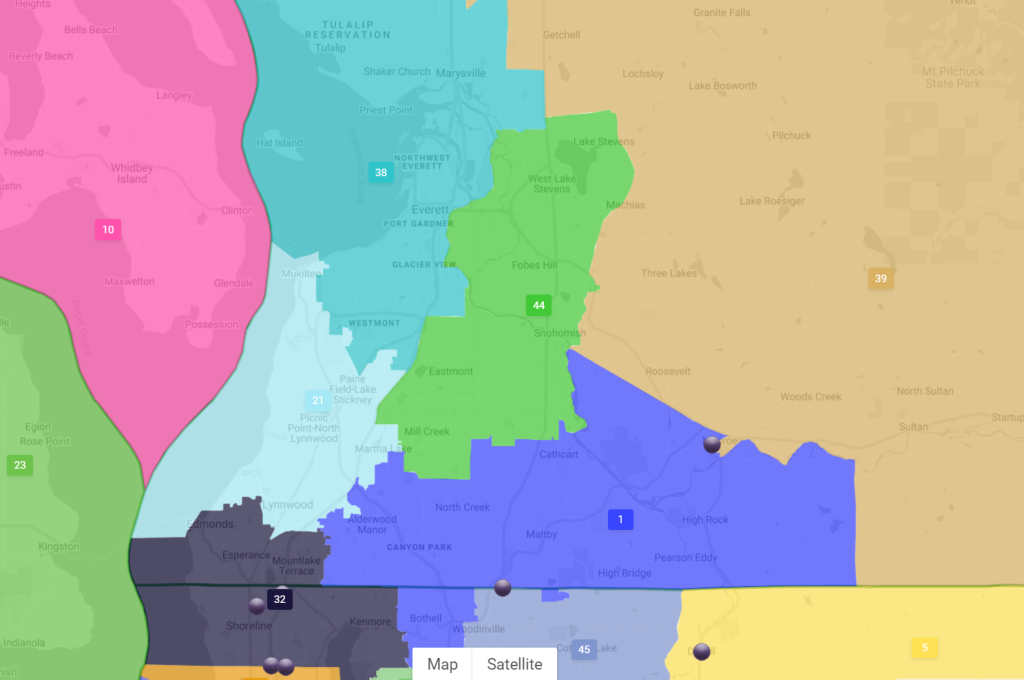

44th District

Another Democratic pickup over the past decade has been the 44th District, which today covers suburbs like Mill Creek, Lake Stevens, Snohomish, and Marysville. With rapid growth in much of Seattle and Snohomish County, the 44th’s borders are likely to shift south or west. Sims’ map opted for a southern shift and in the process dropped Lake Stevens, where State Senator Steve Hobbs lives, and picks up a piece of Everett. In office since 2007, Hobbs is up for reelection in 2022, and, though a Democrat, has often voted with Republicans and opposed climate bills while promoting regressive car-centric policies as chair of the Senate transportation committee. Walkinshaw’s map would keep Lake Stevens in the district and shift the borders elsewhere, losing Marysville and the western unincorporated edge of the district. The State Democratic Party put forward moderates like Hobbs and Mullet in suburban fringe district hoping they’d fare better than stauncher progressives. But as these districts have shifted to the left while the senators have not, that bargain seems less prudent and necessary.

If the district borders do end up moving on him, Steve Hobbs could still move residences to stay in the district boundaries. Even so, a tough progressive challenge may wait for him.

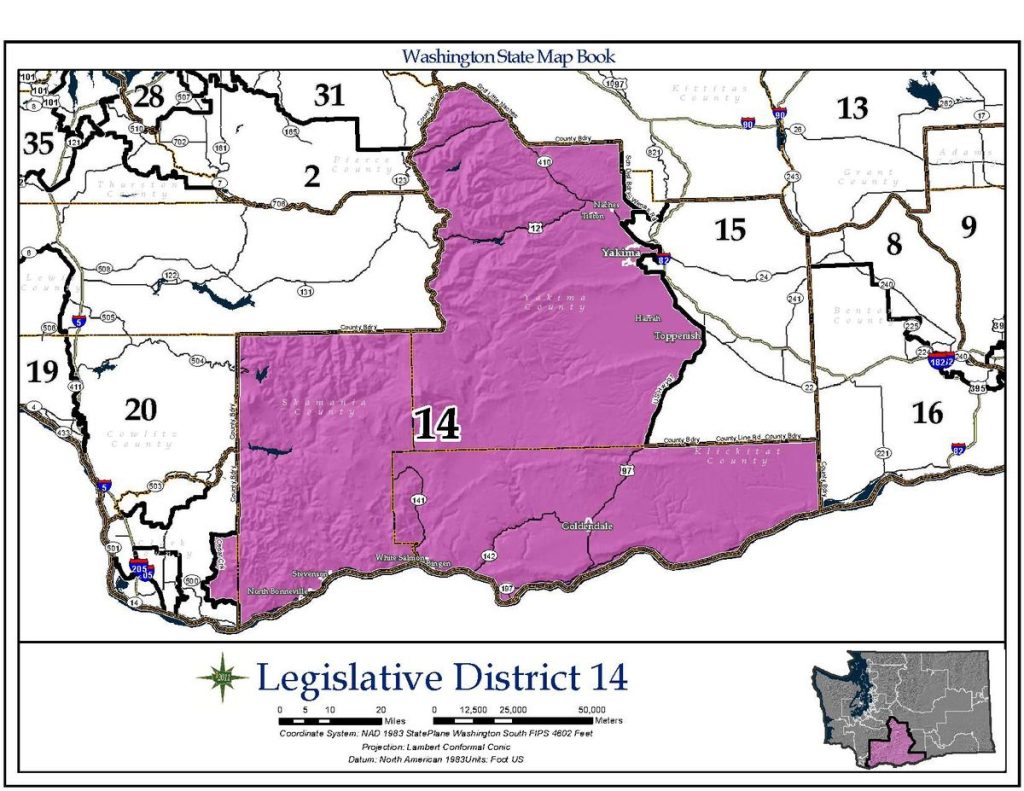

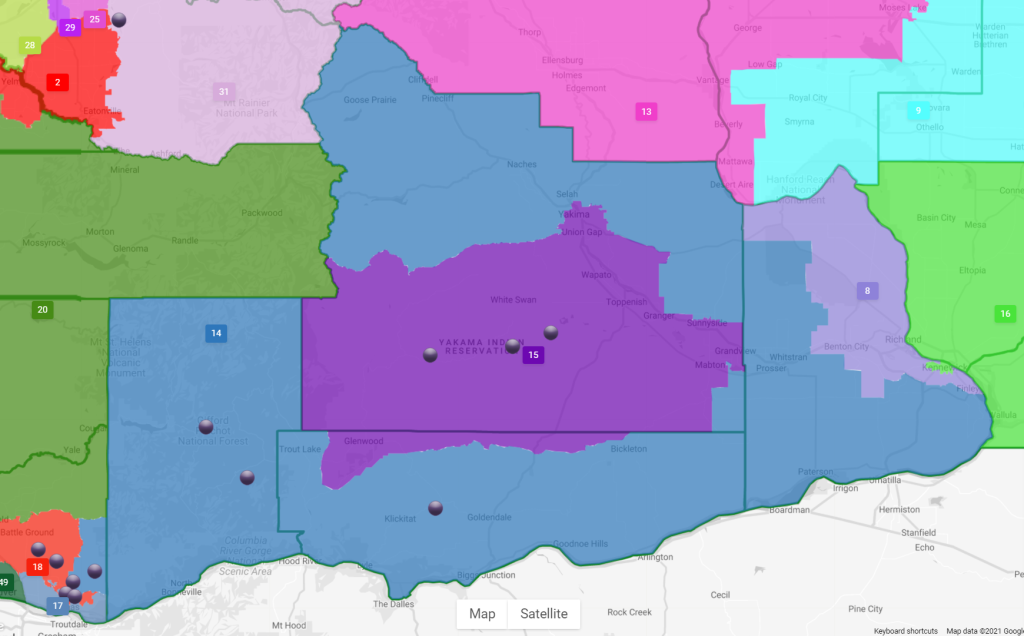

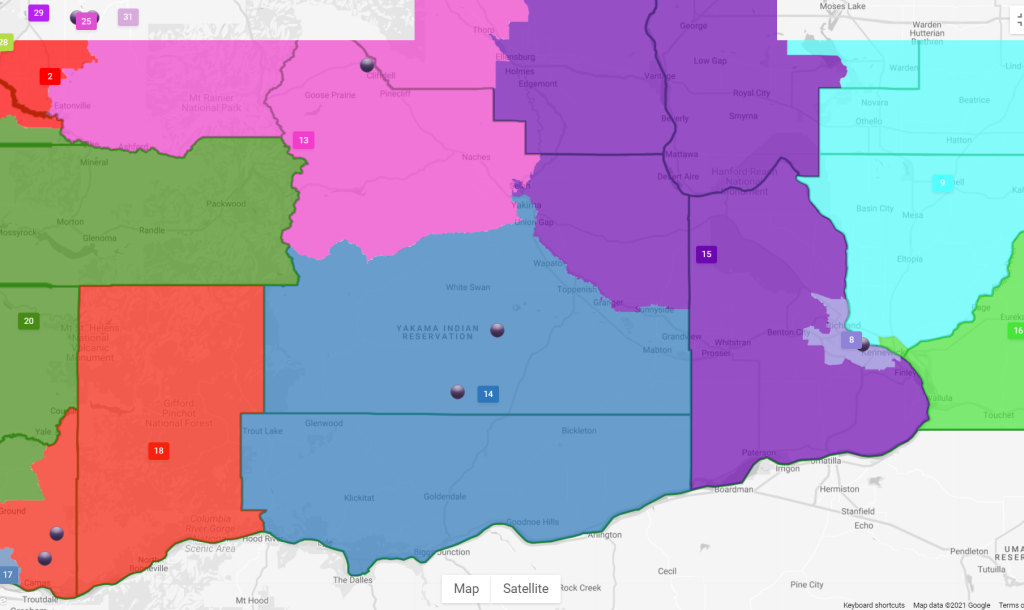

14th District: A Yakima District?

One big goal for some progressive groups this cycle has been advocating for a new Legislative District that does not split up and dilute the Yakima tribe’s reservation and the Latino populations centered in the Yakima valley. One specific example: the Washington Census Alliance has set a redistricting goal of consolidating Latino voting power in a legislative district more centered in Yakima, where Latinos are about half the population. Presently, the Latino population and the Yakima Reservation are split between the 14th and 15th districts, with both roughly constituting 60/40 districts in favor of Republicans. Creating a district that doesn’t split the reservation and Latino population centers in the Yakima valley could create a more evenly split district where Latinos and Yakima tribal members have a less diluted voice and Democratic candidates have a chance.

Today’s 14th District with the 15th just to the east. (Washington State)

Sims renames the 14th as the 15th District and centers it around the Yakima Reservation with the 15th enveloping it like a donut.

Walkinshaw put the 14th to the south with most of Yakima and all of the Yakima Reservation included. The 15th is to the east.

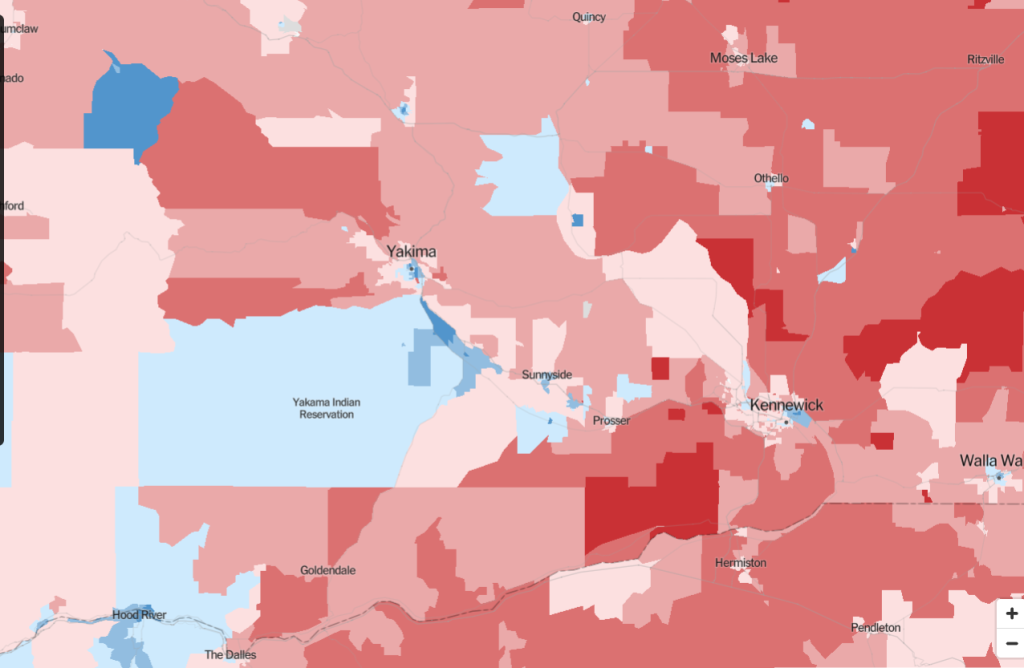

Yakima city and reservation supported Biden in 2020, but much of the rest of the area was Trump country. (Credit: New York Times)

Walkinshaw’s map makes a dramatic demographic transformation with his new 14th District a majority Hispanic district at 96,394 Latinos (61%) and 11,388 Indigenous residents (7%), which would constitute the highest concentration for either racial group in any state district. Sim’s map goes even further with 102,379 Hispanic residents in her 15th District constituting 65% of the population, and slightly more Indigenous residents at 11,426. Sims accomplishes this with the 14th as a donut, and the 15th a donut hole within it. There is a pocket of Democratic voters across from Hood River (which ends up separated from the Latino-majority district in Sims’ version), so it’s not clear which map would have the stronger partisan split.

Looking ahead

The Washington Redistricting Commission will now have the task of taking their four disparate maps and finding one they all agree on. If the commission cannot agree on a map by the November 15th deadline set out in the State Constitution, responsibility will pass to the Washington State Supreme Court to determine the new boundaries.

Correction: An earlier version incorrectly stated Mark Mullet defeated Dino Rossi in 2012. His opponent was Brad Toft.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.