A working group has spent a year analyzing Seattle’s design review process. Here are their suggestions for improvement.

When most new mixed-use, multifamily, and commercial development projects are proposed in Seattle, they undergo a locally controlled and mandated city process called design review. The program works like this: volunteer design review boards offer guidance intended to ensure new buildings fit harmoniously into their surrounding neighborhoods based on characteristics like bulk, scale, and aesthetics. Once a design has met their conditions, the design review board grants a recommendation that clears the way to the developer getting a building permit, but the board can also make the project come back again and again if it finds the architects’ work wanting.

Relatedly, the design review process has drawn criticism from housing advocates who believe it is driving up housing costs by slowing down the production of new housing. They point to a recent ECONorthwest analysis that found permit times were increasing and exceeded 18 months on average for projects undergoing full design review from 2010 to 2020. Developers report Seattle’s permit times can be three times longer than on similar projects in Tacoma’s more streamlined process.

For nearly a year, a working group has been meeting to analyze the current design review process and brainstorm meaningful ways to reform it. The group is made up of representatives from Seattle For Everyone, Share The Cities Action Fund, AIA Seattle, non-profit and private housing developers, as well as land use attorneys, residents, and environmentalists. Their recommendations have been recently published with the goal of sparking an “earnest conversation” around the design review process. They will be presenting their recommendations at a lunch and learn session hosted by Share the Cities Action Fund on Wednesday October 6th at 12pm.

Seattle has been taking steps toward reforming its design review process for years; however, the pandemic offered a test case for expanding administrative design review, which is completed by city planners resulting in a faster and more affordable process, and increasing public access through the use of digital meetings. It has also opened up the thorny question of whether full design review is even really needed for residential projects. These changes have inspired advocates to push for further reforms.

Why is design review viewed as problematic?

“Design review is a continuation of practices like exclusionary zoning and redlining that are used to keep out unwanted neighbors and separate communities,” Laura Loe of Share The Cities said in an email after all fifteen housing advocates who applied failed to be selected for seats on volunteer design review boards last July. “We aren’t getting a more beautiful city, it isn’t more climate friendly, and it isn’t more affordable. We have a choice here to take care of a laundry list of reforms for design review or maybe we just don’t need it at all.”

To back up claims of harm inflicted by the current full design review process, housing advocates can point to standout examples like the Queen Anne Safeway redevelopment project. The project, which will eventually bring 323 new homes, including 29 affordable homes, above an expanded Safeway grocery store along with streetscape improvements, was held up last December when the West Design Review Board withheld its approval over questions about minor design features like the size of planters and modulating storefronts. Their decision further delayed a plan — which has been in the works since the Obama administration — to bring much needed new housing to what is now mostly a surface level parking lot.

While defenders of the design review process may cite the Queen Anne Safeway redevelopment project as an outlier, the working group discovered “systemic patterns” related to flaws in the current design review process that “merit the City of Seattle’s attention and consideration.”

Problems highlighted by the working group include:

- Delays: Design Review delays are growing. The delayed process adds direct costs to housing and future rents.

- Unpredictable processes: Discretionary processes are inconsistent and unpredictable and have a direct impact on project schedule and delivery of housing units. This includes well-documented instances when high quality projects are held up for subjective reasons and/or despite having broad community support.

- Misuse: Design Review is being misused as a tool to stop or slow development rather than encourage good design.

- Lack of diversity: The boards themselves often lack diversity of perspectives, despite the stated intent of boards to represent a range of perspectives.

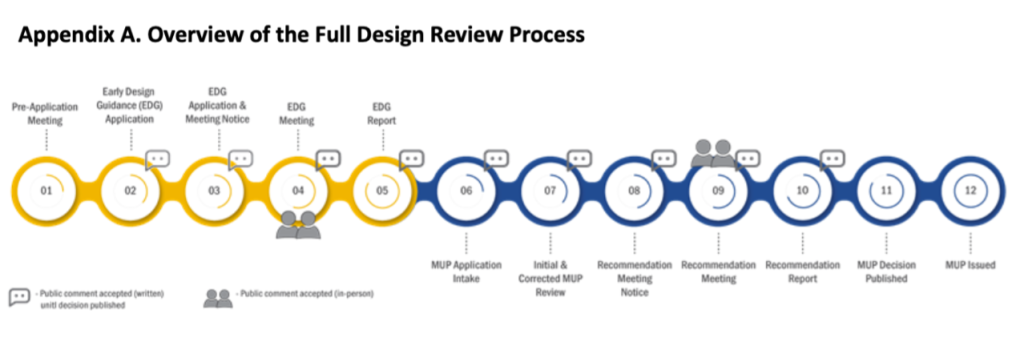

Even in the best case scenarios, the full design review process is rigorous and expensive, unfolding over twelve steps. The working group has identified many ways it believes the process can be made faster, more efficient, and less costly.

,

What suggestions for reforming design review are on the table?

The working group has divided its recommendations into two parts: legislative and administrative. Its first legislative suggestion is a proposal to change the threshold for full design review so that it matches infill SEPA (State Environmental Protection Act) requirements. This would mean projects with up to 250 homes Downtown/South Lake Union or up to 200 units in urban centers and urban villages would be exempt from design review. However, the working group is prepared to go further; they have suggested that all housing projects could be exempt from full design review.

Such a suggestion is bold. In the case that it does not gain traction, additional legislative recommendations have put forth, including making online design review meetings permanent, creating a hybrid administrative design review option that would allow for public comment, streamlining design review guidelines using a race and social justice framework and emphasizing climate goals, examining fees charged through design review by city planners to increase accountability and track time spent, and more.

From an administrative standpoint, the working group has presented several suggestions for improvement as well. First among them is the recommendation that the City establish weekly first-come, first-serve “office hours” in which development applicants can consult with land use planners to determine if their projects are on track. In the event that design review boards continue, they would like to see board chairs receive training on how to better management and facilitate meetings, with a special focus on how to meaningfully engage with applicants during board deliberations. The goal for the training would be to keep meetings on track, saving both time and money spent on city staff who attend.

Additional administrative suggestions for time and cost savings include removing redundant inclusionary zoning reviews, allowing for architects to present for up to 30 minutes in the case of “complex” projects without extending design board deliberation time, making sure complex projects are staffed by both a senior and junior planner, requiring annual evaluation and publication of design review times and establishing performance targets, and reducing the number of projects required to go through early design guidance.

The working group references that many of these suggestions were adopted from a policy report presented to Mayor Jenny Durkan by the Seattle Affordable Middle-Income Housing Advisory Council in January 2020.

The Urbanist has been reporting on efforts to improve Seattle’s design review process since 2015. Since then the scope of the full design review process has only grown more complicated and time-consuming. However, if committed advocates like Seattle For Everyone, Share The Cities Action Fund, and AIA Seattle have their way, the City and its residents will finally dig into achieving meaningful design review reforms that further housing affordability in a city that sorely needs it.

Check out their design review reform recommendations.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.