Livability would flourish in surrounding neighborhoods if cars were removed from one of Seattle’s deadliest and most polluted streets.

Today’s Aurora Avenue in Seattle is a wall, a loud, dangerous, polluted wall that divides communities. However, solving Aurora’s problems also provide an exciting opportunity to rethink sustainable mobility, undertake visionary climate protection, add ample social housing, and provide much needed high quality open space.

Doing so would require a bold change: removing car traffic from Aurora and replacing it with tramways, bike lanes, and parks and plazas at intersections.

Critics might say that such a change is impossible, but cities the world over are re-thinking mobility in the midst of changing work patterns due to Covid, our worsening climate crisis, and the pedestrian safety crisis. Visionary Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo is in the process of removing half of the on-street parking spaces and converting them to parks, wider sidewalks, and bike lanes. Cities from large to small are developing plans to remove cars, while simultaneously increasing livability and mobility. Amsterdam, which was choked with traffic in the 60s and 70s, is at the forefront of this — but they aren’t stopping with where they are today. The Agenda Amsterdam Autoluw (Autoluw is Dutch for nearly car-free) includes incredible transformations — both underway, and in planning — to make space for green mobility, eliminate thousands of on-street parking spaces, and ensure a healthier and cleaner city for present and future residents.

The International Panel on Climate Change report released in August also highlighted how climate change is, at this point, inevitable. Drastic courses of action will be needed to slow the extent of warming, as well as mitigate and ruggedize against unavoidable long-term effects. Seattle’s heat dome may no longer be an anomaly — wildfire smoke now has its own season — and we are constantly reminded of the devastation that downpours can do — Germany’s floods from this summer alone will cost $35 billion for recovery.

Unfortunately, Seattle’s own climate goals will continue to be missed with a mayor and transportation department that continue to prioritize the least sustainable form of transportation over efficiency and livability. Seattle is in the midst of a massive housing crisis, and a deepening climate crisis, exacerbated by our city’s inability to meet our climate goals. The main reason we are unable to meet our climate goals is private transportation. Simply replacing combustion engine vehicles with electric vehicles does nothing to address the worsening pedestrian safety crisis, the embodied carbon of parking and sprawl, rampant noise pollution, or the die-off of salmon populations. Without a re-visioning around sustainable movement of goods and people, Aurora Avenue will stand as a stark memorial — much as the SR-99 tunnel does — of failed leadership on climate action and safe, livable streets.

The current situation sets up a future environmental justice disaster

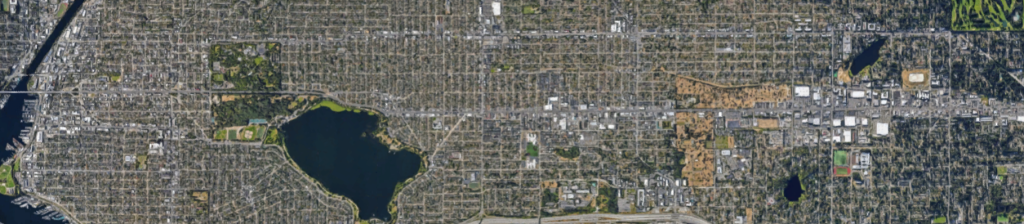

There are four Urban Villages (UVs) that straddle or abut Aurora Avenue — Fremont, Wallingford, Aurora-Licton Springs, and Bitter Lake. Greenwood’s UV boundary is just a few blocks to the west. These UVs all have massive deficiencies of park and open space, with almost no major spaces planned to be added in the future. However, much of the land on either blockface of Aurora is zoned for buildings 55 feet to 75 feet in height. Thus, as Aurora continues to develop, it will see five- to seven-story buildings along either side. Unlike in walkable European and Asian cities, this density steps down quickly to low-rise and single-family housing. An Aurora with fully developed buildings on either side would put thousands of residents directly facing an incredibly dangerous street on which few given the choice would prefer to live.

Nearly half of Aurora Avenue doesn’t have sidewalks. It is also one of the noisiest streets in Seattle. Motorists routinely drive double the speed limit, and it remains one of the deadliest streets in the city with yet another deadly crash just last week. All of this occurs with six elementary schools, two middle schools, four high schools, several private schools, and at least 30 preschools and daycare centers within a half mile of the road. Our families avoid walking or biking on it due to its numerous problems, and trying to cross in the handful of places where it is actually legal requires waiting several minutes. I personally can’t imagine living on Aurora. Simply adding tens of thousands of new residents on it, as many people advocated for during Housing Affordability Livability Agenda (HALA) outreach a few years back — without addressing the pollution, noise, and safety impacts, let alone its inaccessibility, will do nothing to make for future livable neighborhoods in the corridor. Instead, business patrons, children and families frequenting nearby schools, and new residents will be situated in an environmental justice disaster. There is, however, another way forward.

Today, there are parts of Aurora that see less daily traffic than Holman Road, or even Greenwood Avenue. The Seattle Department of Transportation’s 2019 Traffic Flow map shows that much of the northern section handle only 20,000 cars per day, each way, a number that could be moved every two hours on a light rail or RapidRide line.

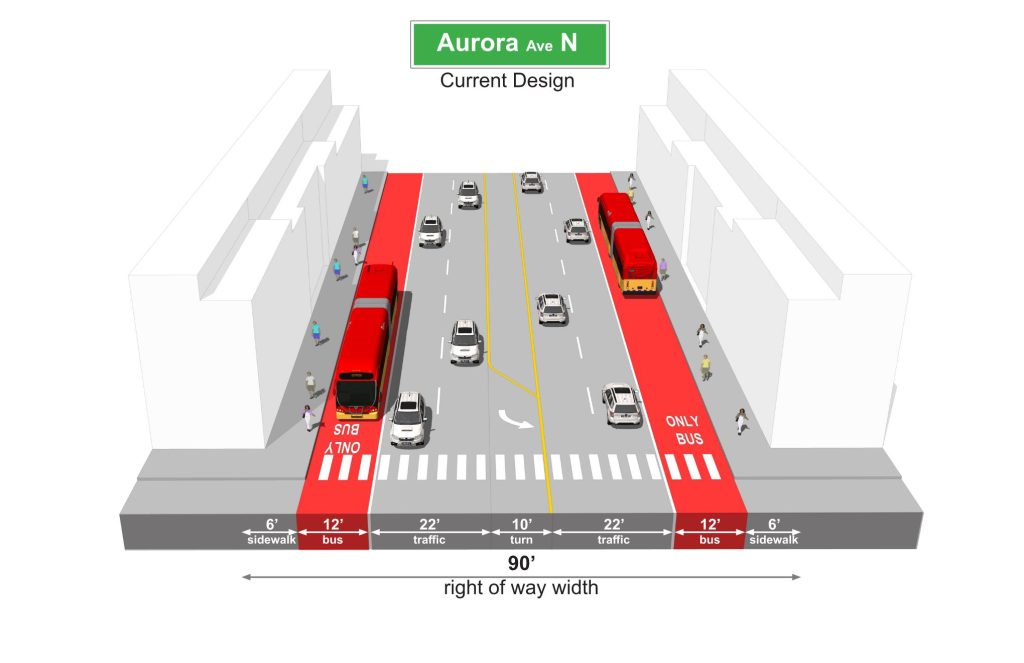

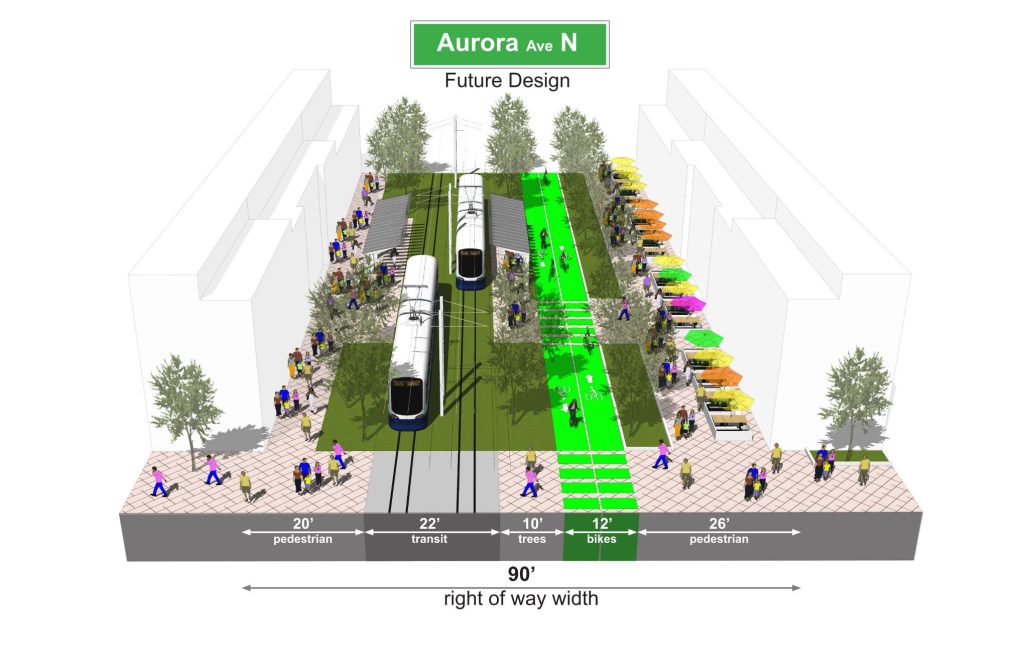

But what if we flipped the script? What could Aurora Avenue look like in the context of a 15-Minute City? What if we used this upcoming re-visioning process as an opportunity to reverse the deleterious effects of Aurora’s status quo? The community may be envisioning fewer lanes — but how many are actually needed? What if I told you the right amount of general purpose lanes for a climate-resilient avenue, is zero? A car-free, tree-lined Aurora Avenue; running from downtown Seattle to Shoreline, with bike lanes and center-running, grass-filled tramways, space for plazas and parks at intersections. This would be a massive game changer. It would dramatically improve walkability and livability for all the adjoining and straddling neighborhoods. This is what it could look like…

Car-free Aurora: a statement for positive climate transformation

The future could be a dense, green corridor prioritizing sustainable mobility, re-stitching existing neighborhoods and accommodating new and growing ones, providing ample jobs with a strong economic and social mix of residents. It would be a sustainable neighborhood development found in places like Tokyo or Europe, but non-existent in the United States. Vibrant and distinctive, the new Aurora could provide needed urban amenities for new and existing residents and businesses. This proposal is not unique. Seattle Subway proposed a light rail line on Aurora several years ago, referencing the E-line’s daily ridership of 18,000 passengers, as well as the corridor’s 33,000 total passengers. The RapidRide E Line is the bus with the highest ridership in Washington.

Such a transformation would take a corridor that is difficult and dangerous to cross, and drastically improve accessibility for pedestrians and those using other wheeled modes of transportation such as scooters, wheelchairs, and bicycles. It would provide ample places to eat outdoors, without the continuous drone of traffic or eating exhaust with your enchiladas. It would enable residents to get their children to daycare or school without navigating an inhospitable environment, or having to wait longer than two minutes just to cross dangerous intersections. It would encourage middle school and high school students to safely and independently get to and from school. Imagine walking to drop off your kiddo at daycare, hopping on a tram line, and being whisked quickly into downtown.

This is what daily life is like in many cities Americans love to travel to, and we could have this, too! A car-free Aurora would be a dramatic change from the status quo. It would be a statement for a climate positive transformation. Broad sidewalks, without being marauded by motors. Bike lanes and a grass-lined streetcar, connecting Shoreline to Seattle’s streetcar and bike networks downtown. Effective stormwater management. Open space, where none exists. It would mean incredible opportunities for businesses, cafes and restaurants to spill out into the neighborhoods. It could mean thousands of trees providing ample shade in summer and helping to clean the air, while mitigating the urban heat island effect. It would be peaceful, tranquil, and incredibly livable.

Designing a car-free Aurora would necessitate a re-working to accommodate logistics, but major cities from Tokyo to Zurich have shown deliveries can be timed in order to work well with pedestrianized and car-free streets. Perhaps we could even see logistics via tramway, as was recently piloted in Frankfurt. To accommodate the north-south movement of rapid transit, most east-west intersections would remain open to bikes and pedestrians, but cars would be limited to arterials. This does a beautiful thing — it stops cutting through neighborhoods, effectively turning the ends of these neighborhood streets intersecting Aurora Avenue into community amenities — a true opportunity to re-democratize segments of our public right of way. Farmers markets, playgrounds, spray parks, petanque courts, food markets spilling out onto plazas, pea patches, dog parks — the ideas are numerous — could all be added. Naturally, the City should work with developers and residents to cooperatively plan such a future.

We need to be thinking about reorienting the city streets and neighborhoods to be more resilient to climate change, especially with over a million more people moving to the region in the next few decades. At last count, over 1,000 homes are currently planned and under construction on this stretch of Aurora Avenue. We must prioritize sustainable mobility, while improving health outcomes and livability for all residents — both current and future.

A car-free Aurora Avenue could, in effect, be a vibrant linear park, leading the way to the very transformations we need to meet out climate goals. Cities change. Streets change. Unfortunately, our climate is also changing. We can and must change our city as fast as Amsterdam changed itself in the 1960s, or how Paris is changing itself, today.

A better world — and a better Aurora Avenue — is possible.

Disclaimer: Ryan DiRaimo is a founding core member of the Aurora Reimagined Coalition (ARC), but the contributions to this article are not a representation of ARC’s community-led vision. ARC is envisioning a future for Aurora that has support of neighbors and businesses, to reimagine a safe future for the road. For more about ARC and how to get involved, visit www.got99problems.org to learn about the coalition’s active pursuit for change.