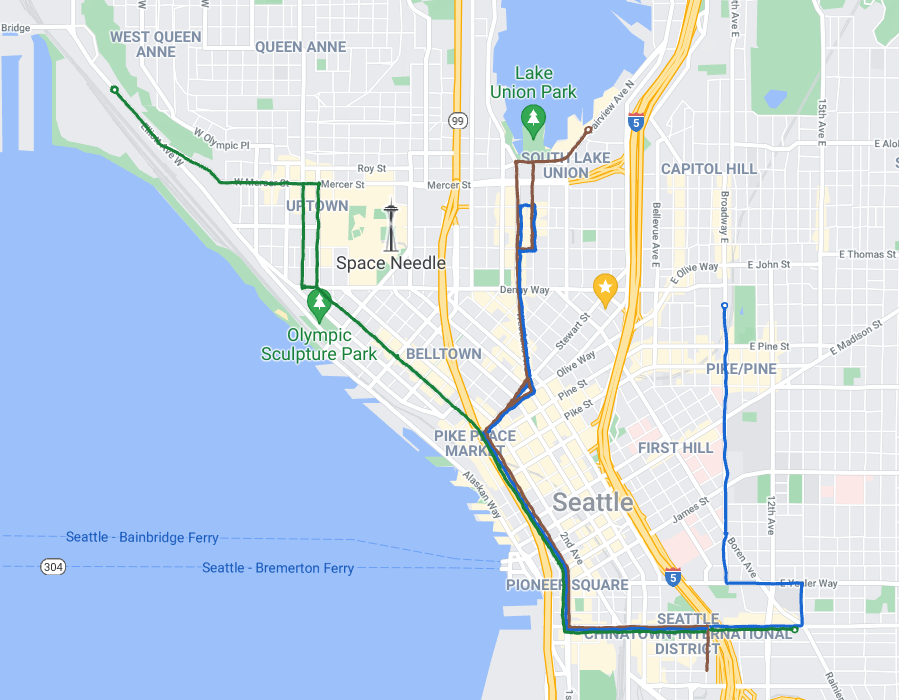

Line extensions into neighborhoods like Belltown and the Central District are part of a set of solutions that would improve Seattle’s streetcars.

Seattle has had a troubled recent history with streetcars. The popular Benson Waterfront Streetcar was closed in 2005 without public input. The South Lake Union Streetcar was built soon after as a way to encourage development for South Lake Union, but at only 1.3 miles is too short to be useful transit. The First Hill Streetcar was supposed to replace the lost First Hill light rail station, but instead was built on an alignment that grazes the edge of First Hill. Worse, it was compromised into a mixed traffic mess that struggles to be competitive with other modes of transportation.

Finally, the Center City Connector (CCC) streetcar project was supposed to correct the failures of the two existing lines by providing a longer route running in an exclusive lane of traffic. It was also anticipated to increase ridership to an estimated 35,000 daily passengers by 2035, a substantial increase. However, the CCC was put on permanent freeze by Mayor Jenny Durkan just as construction was starting because she felt the streetcar would be a bad investment for Seattle taxpayers.

It might seem that streetcars are just doomed in Seattle and that efforts should focus on improving bus service and Link light rail instead. However, recent events have also shown that dreams of a citywide subway system may be more expensive and take much more time than we hoped. Additionally, bus projects that once held much promise have been significantly scaled back; becoming shorter, with less exclusive lane running, and even losing electrification options in the case of Madison RapidRide G Line. Given all of the problems these projects are seeing, one might think that city leaders aren’t that concerned with improving transit outcomes or consider climate change an issue we need to take action on any time soon. The recent International Panel on Climate Change report makes it clear; we don’t have the luxury of waiting around for multiple decades to make radical changes to our transportation infrastructure. Given how poorly we have done with quickly rolling out rapid transit projects up to this point, perhaps it is time to reevaluate the CCC project and see if we can use projects like this to make actual radical transportation changes that Seattle sorely needs.

What makes a streetcar useful transit?

It wasn’t always this way, as we’ve noted at The Urbanist previously; Seattle was built on streetcars and once knew how to build effective lines. These days though, one must look at existing legacy streetcar systems in other cities to see how they were once built. I currently live in Tokyo, walking distance from the city’s last remaining streetcar route. Though it owes its existence to local activists who fought to keep it running, the reasons why it are still useful are pretty straight forward: it has its own lanes and rarely mixes with traffic, it’s more predictable and faster than a bus, it has multiple stops where riders can transfer to major rail lines, and it runs through a number of areas that are otherwise poorly served by the major train lines. When compared to what Seattle has already built, it’s pretty clear where Seattle’s streetcar lines need improvement. Seattle’s streetcar routes need more exclusive lanes, longer routes, better transfer points, and routing through neighborhoods underserved by current and planned higher-speed subway lines.

Adding more exclusive lanes

One of the most attractive features of the CCC project is the addition of exclusive, center running streetcar lanes on 1st Avenue. It’s pretty clear that this does not go far enough though. To truly improve the usefulness of the South Lake Union Streetcar (SLUS) line, all of the shared streetcar lanes on Jackson Street ought to also be converted to exclusive streetcar lanes. This serves two purposes: it frees up more space for more frequent streetcars but it also calms the street and naturally lowers the speed of the cars sharing the street to reduce potential collisions with streetcars or riders who need to cross the street. With a solid core of exclusive lanes on Jackson Street and 1st Avenue combined with some exclusive running added, the SLUS line could transform that too-short line into something much more useful. These exclusive lanes could be used for much more though, and adding more stations beyond the CCC project ought to be considered in order to make the most effective use of this investment.

Adding a third line through Belltown

If streetcars do better with dense neighborhoods that have poor access to higher capacity rail and subway systems, one could hardly pick a better target to add than extending further up 1st Avenue to include Belltown. This idea is attractive enough that it was included in multiple versions of the earlier streetcar system plans. After Belltown, it would be fairly easy to also add Smith Cove to the line both as a place for a trolley barn to store streetcars, but also to add access to the new Expedia Campus, which could help convert Eastside commuters to transit riders a decade or more earlier than might otherwise happen if we simply wait for the Ballard Link line to be extended this far. This isn’t intended to compete with the Ballard line, but could take pressure off of the system much earlier and could serve as an attractive transfer point in the system should the streetcar be extended further.

Further extensions to serve the Central District

If the changes above are used to create three line system down 1st Avenue and Jackson Street, it may also make sense to extend these lines further to provide service to a few other neighborhoods that may be underserved by the current planned Sound Transit lines. Though Judkins Station will serve part of the Central District, quite a large portion of the neighborhood, including its densest areas and business districts, will be well out of walking range. Extending either the SLUS line or the Belltown line further up Jackson Street would provide better transit options to a large portion of the city that will be well outside of the walkshed of Sound Transit’s Link light rail system for some time.

One challenge this routing faces is that with only two travel lanes and two parking lanes it may be a challenge to get exclusive center running lanes along this street. Alternately, branching down Rainier Avenue S towards Mount Baker Station would provide two interesting transfer opportunities at Judkins Park Station and Mount Baker Station but would not serve quite as many people as a Jackson routing would. Either of these routes may have a displacement effect that they may have to reconnect with as well. Finally, extending the Smith Cove section out to Magnolia over a new transit-oriented Magnolia Bridge could present an opportunity to boost transit service to one of the least served neighborhoods in the city while also being the impetus for a major rezone and redevelopment of the neighborhood. (This is an idea that will be discussed further in a later article.)

Interactions with bicycles

One of the most controversial portions of these streetcar projects is the interaction with bicycles. The current proposed CCC corridor is a little tight to currently include bike lanes, so they were not included in the project, but extensions past this corridor involve wider segments of road and should consider including them. Where bike lanes are added, they ought to be as far away as possible from the train. Where the train takes center lanes, the bicycle should be on one side or the other. In couplet pairs (such as Queen Anne Avenue N and 1st Avenue N in Uptown), the bicycle lanes should be on the opposite side of the street to reduce interaction with the streetcar. In the case of Queen Anne, the curb lane should be shared with buses to make transfers between trains and buses easier as well.

Other improvements

In addition to the adjustments listed above, there are a few more changes that could significantly improve the shared streetcar corridor. The platforms on 1st Avenue and Jackson Street should all be designed to handle multiple streetcars. Longer platforms could better handle streetcar bunching should two streetcars arrive at one station at the same time. Additionally, longer platforms could support longer streetcars in the future as well as linked streetcars (similar to how link light rail vehicles attach) allowing a single driver to carry as many as 220 passengers (double the current 120 maximum load on streetcars). This is more than the maximum capacity of the longest 60-foot metro buses and could greatly improve the system to handle downtown loads should there be a tunnel shut down on the Link system.

Fortunately, most of the platforms on Jackson Street are already longer than the platforms in the rest of the system and only the platform at 7th Avenue S and S Jackson Street and at the end of the line at 1st Avenue S and S Jackson Street. The platform at 7th Avenue S may need to have special accommodation for longer vehicles (such as only using the front or back doors), but the current terminus at S Jackson Street and 1st Avenue S could be moved from S Jackson Street to 1st Avenue S where it could both be built to support more/longer vehicles but could also enable the lanes on Jackson Street to stay in the center lane and be made streetcar-exclusive, which is a better alternative than what the current plans call for. Finally, the shared tracks on both roads should be fully electrified so that new streetcars don’t need to be special order battery-running hybrid vehicles. This will make future streetcar purchases less expensive and stressful (and avoid the delays the First Hill project faced).

Expanding streetcars is a climate-friendly choice

Functional streetcar lines have exclusive lanes, transfer points to faster transit modes, and connect to neighborhoods otherwise not directly served by transit. Seattle’s current streetcar lines struggle on these points, but an exclusive corridor carved out down 1st Avenue and Jackson Street could help address these issues and solve the South Lake Union line’s biggest issue of being too short. Using the shared lanes to make a third line to Belltown could give Seattle the opportunity to build a completely exclusive line that brings underserved high population centers and growing employment centers to the system and bridges a lot of the downtown transit gaps many years before the subway lines finally arrive.

These lines could also be extended to reach more residential areas that may be well outside the walkshed of the currently planned light rail network. Bringing all of these ideas together could begin to provide a framework of how both build more high capacity transit to give better options to clogged streets and potentially soon enough to make a bigger difference on the climate change front. It may not be a perfect solution, but we may not have the time and money we would need to build the ideal solution before it’s too late to make any difference on the impending climate disaster.

Charles Bond

Charles is an avid cyclist that uses his bike as his primary mode of transportation. He grew up in the Puget Sound, but is currently overseas living in Japan. He covers a range of topics like cycling, transit, and land use. His time in Tokyo really opened his eyes to what urbanism offers people and has a strong desire to see growth happen in Seattle.