As of Thursday, Seattle Public Schools (SPS) had six days of school and six days of late school buses. It’s a local impact of a national school bus driver shortage. Around town, the shortage is getting less short but it’s still pretty noxious. On the first day of school on September 1st, 66 routes were late, impacting 42 of the District’s 113 schools. As of Thursday, September 9th, it was 56 delayed routes impacting 38 schools. Most were a delay of one hour, but some were two hours.

Though I have gripes with the school district, a bus driver shortage is not one of them. SPS has been put in the position to need an outsourced transportation provider. This should not be the case. A functioning city would be able to distribute kids where they need to go, and do it without yellow buses. But there’s a strange distance between the city and its schools. A distance that drains life out of Seattle’s neighborhoods and classrooms. Buses are just a part of the city’s go-your-own-way attitude towards its public schools.

From the physical distance between Seattle’s government and its superintendent to the functional distances in policies on levies and school siting, the ties between city and education are tenuous. It bubbles to the surface when a city with a growing transit system can’t get enough school buses. But the larger issue is that we don’t build a city that supports kids.

So Very Far Apart

Up front there is an inexplicable physical air gap between City Hall and SPS Headquarters. There are two stadiums, an interstate, and another half mile of railroad tracks between the mayor’s office and the John Stanford Center for Educational Excellence. If power is about proximity to authority, the distance between two of the city’s most important governing bodies is insurmountable.

This sounds like a weird thing given telephones. But it speaks to a level of importance that the city holds its agencies. In many other places, school district headquarters and city hall are right next to each other. New Yorkers need only walk across City Hall Park to bridge the gap. Chicago’s mayor and superintendent are separated by a plaza with a Picasso. San Francisco City Hall and school headquarters are on opposite sides of Van Ness Street. Los Angeles’ buildings are separated by a highway, but it’s Los Angeles. Seattle’s city government has time and place to catch a baseball game between their offices and SPS HQ.

The physical distance is a manifestation of the arms length relationship between the city and the school district. Talk of a closer relationship results in howls of “mayoral takeover” and concern that it’s a fast road to school privatization. Frankly, the incompetence of the current administration can shelve a takeover for a few more months. However, the schools and the city need closer ties.

It’s not just headquarters. There’s distance between City Hall and any school. The closest school to City Hall is Bailey Gatzert on the other side of Boren Ave in Capitol Hill. It’s a mile uphill, and requires crossing Interstate 5. There is literally no safe route to a school for someone walking out of City Hall.

Besides an unfortunate impact on city employees, the lack of a downtown public school is an absurd failure for the city. The city’s fastest growing neighborhood warrants an elementary school and more. There’s no community center serving downtown, and the parks are geared towards a very limited, much younger set. The lack of foresight by both the City and the District on this is ridiculous but predictable.

Schools appeared in Seattle’s last comprehensive plan under public services. In that section, the city relied on SPS’s plan for future student enrollment. It’s a birth model, that uses the number of under-fives to project how many kindergarteners will show up a few years out. Then each grade has an estimate of how many kids carry over. The specifics are discussed in the plan’s Environmental Impact Statement (PDF).

Like so much of the city’s comprehensive planning, this is playing cleanup. A comprehensive plan could look at the locations targeted for growth and lead with infrastructure and services. Instead, it asks a bunch of agencies how they feel about their services and where they can sustain some extra use. Our city’s future includes thousands more residents. We need to put the schools in place up front. Schools should not be a lagging demographic. They should be built as a draw.

The Levy Issue

Any potential new school is at the mercy of the city-district gap another way. Schools are built and rehabbed under the District’s Building Excellence (BEX) Levy. We’re up to BEX V now, which will add a school in West Seattle, three new schools in South Seattle, and three in North Seattle. Other schools will get upgrades to technology and safety equipment. The levy provides nothing in downtown.

Compare that to the Move Seattle Levy which has a list of goals for improvements spread throughout the city, with emphasis on some of the most used areas. This includes safe routes to school. While very far from perfect, the nine-year Move Seattle plan anticipated future needs. The levy is (slowly) expanding the bike network and put in place transit improvements that connect to the opening light rail stations. Even King County Parks Levy looked ahead and said “hey, we’ve knocked down this viaduct, here’s $35 million to expand the Aquarium.” Compared to the way Seattle builds schools, that’s forward thinking.

We will, of course, take a moment to swipe at Washington’s system of levies. Pass a damn progressive income tax and reduce the over-reliance on these pigeonholed BS levies. And raise the car tabs again too. Make the additional fee a calculation of engine size times the area of the vehicle’s grill. You want to drive a two-story death machine, pay up.

Which brings us back to transportation. Understanding the district’s relationship with the city as a gap, transportation is the most interesting illustration of how things tumble in. In the BEX V Environmental Impact Statement, SPS anticipated that, as kids grow, they’ll move away from school buses and towards transit buses.

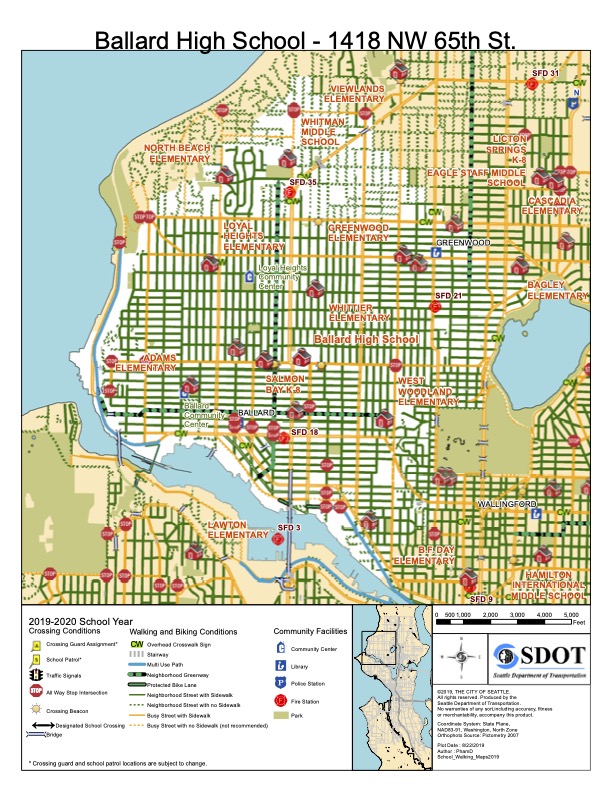

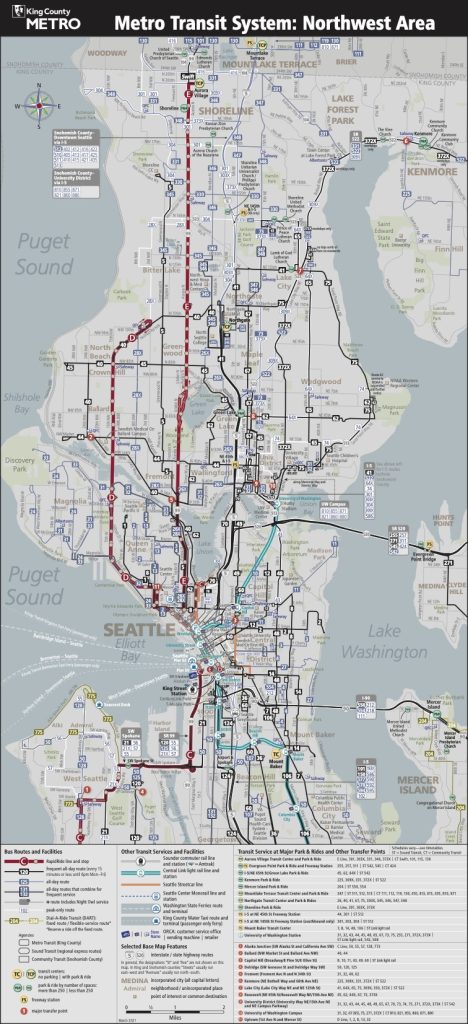

That’s just great, unless you are invested in maintaining a bunch of schools deep in single-family zones without frequent bus service. Even where the city does help the district and produces the Safe Route To School maps, they don’t include transit routes. And, speaking truthfully, the maps are an unreadable mess. That’s a contrast to the King County Metro bus map which is clear, but doesn’t show schools. Just another gap in map form.

A City For Kids, Not A Childish City

This is at the front of my mind because, for the last week, we’ve been one of the families getting a call each day saying the school bus will be late. An hour late both morning and afternoon. We’re very lucky in that we have options for transportation. Many don’t.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have the time to make this a teachable moment and get the kids to school on a transit bus. The kids are as resilient as kids can be though they’re using a public bus for the first time in two years to get to a school that they’ve attended for a year but never been to. Post-COVID transit paranoia is something that many adults haven’t had to get over, but we’re letting the kids test it first.

Riding public transit is a skill. I know this because it’s one I picked up later in life. We didn’t have public transit in the exurb that I spent my teens, so I had to make a deliberate effort as an adult to put away the car and move through the city by bus. This is an effort that many people know, but don’t appreciate that they have gone through.

Like many things, it’s easier to learn as a kid. Learning the skill of riding transit has such an added benefit for kids because it unlocks an entire world to explore. It’s just like the adventure of learning to read, with the entire city as the book. But for a kid, what kind of book is Seattle? Kind of boring, to be honest.

Places don’t need to be Disneyland in order to accommodate children. Really, they don’t even need the sharp edges blunted down. Kids are capable of knowing how to navigate in the places they find themselves, and how to behave when they get there. Even when we don’t give them credit for it. Have you ever heard a kid code switch between school and home? They do it better than adults. Kids are astute at reading a room and changing how they act, for better or worse. Worse comes out when they recognize they’re being disrespected.

Unfortunately, Seattle disrespects kids more often than not. We’ve set up miles of city that should be a grand playground of beaches and parks and interesting neighborhoods. But we cut them off from the schools where kids spend most days and the homes they live and the transit that could get them around. Instead we put kids under constant gaze of a parent as they get shuttled around from a programmed activity to another. Seattle does not raise kids to be trusted. But it can by embracing its schools as a part of the city and as part of the city government.

So much of the issue with delayed school buses wouldn’t actually be an issue if we close the gap between city hall and the school district. We could be looking at better coordination between property tax levies and the sites for new schools. Apartment bans around current schools could be lifted so more kids have access by walking. All of the schools could be closer to the kids that need them as well as bus lines that serve the whole city. Imagine aligning busy neighborhoods and schools with robust park programs, more community centers, and even expanded bike lanes and sidewalks. All of the sudden, you have a city where children don’t have to be infantilized.

The distance between SPS headquarters and City Hall isn’t just a measure on a map. It’s written over and over in Seattle’s broader disfunction towards kids and families. Yes, we’re dealing with a bus driver shortage this week. It was paving playgrounds for parking before and treacherous routes to school before that. And it will be something else next week, repeating until we deal with Seattle’s bizarre and pervasive gap between city and its schools.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.