CA 29 is over, but the debate over how to end homelessness is not

A three-judge panel from the Washington State Court of Appeals has declined a stay request from the campaign for “Compassion Seattle” City Charter Amendment 29 (CA29) that would have blocked King County Superior Court Judge Catherine Shaffer’s order to remove CA29 from the November ballot.

“We have considered Compassion Seattle’s motion and have determined that it should be denied,” the Court of Appeals panel stated succinctly and without providing further explanation for their decision.

“We’re not surprised by the outcome,” said Knoll Lowney, attorney for the plaintiffs in a press release. “State law requires cost-effective and coordinated homelessness policies, which is why the law does not permit an initiative to impose up to a billion dollars in unfunded mandates without expert input or accountability.”

In a sign of palpable relief, House Our Neighbors, a coalition that formed in opposition to CA29 tweeted, “It’s over! Let’s go win housing for all!”

The CA29 campaign has posted a statement on their website expressing they are “deeply disappointed” in the decision, and that the “rejection of our emergency appeal motion means that Seattle voters must change who is in charge if they want a change to the city’s failed approach to addressing the homelessness crisis.”

The campaign also asserts they will “continue to share evidence that our amendment’s approach can make a necessary and noticeable difference for those living unsheltered in our parks and other public spaces.”

Opponents have argued that CA29 would have enshrined the right to sweep homeless encampments in the city charter and resulted in an unfunded mandate that would have undermined regional efforts to address the homelessness crisis.

“We invite those who backed CA 29 to work with us and with the King County Regional Homelessness Authority by committing to secure the resources and housing necessary to achieve real and lasting solutions to homelessness,” said said Alison Eisinger, executive director of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, which was one of the plaintiffs in the case.

Homelessness policy differences divide candidates

With thousands of people sleeping unsheltered and in vehicles on Seattle’s streets every night, the homelessness crisis will remain an area of critical concern for Seattle voters.

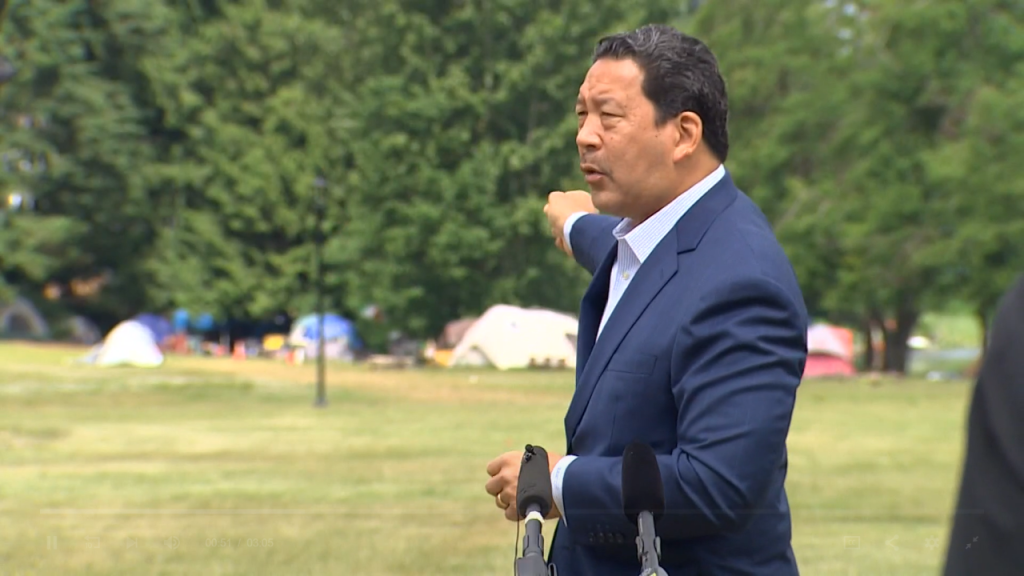

Yesterday Mayoral candidate and former city council president Bruce Harrell spoke in front of a controversial homelessness encampment in Woodland Park near Green Lake and outlined his plan to address homelessness, which bears many similarities to CA29, Publicola‘s Erica C. Barnett reported. Harrell also used a homeless encampment near an elementary school in Bitter Lake as a backdrop for a June press conference in a clear campaign theme that appears aimed at appealing to his base in wealthy single-family zoned neighborhoods.

Harrell, who had backed CA29, has pledged on his campaign website that he would maintain certain policies outlined in the amendment, such as dedicating 12% of the City budget to homelessness services, while stepping up the pace of emergency housing development. CA29’s writers had envisioned the City would create 1,000 units of affordable or emergency shelter within one year of passage, and then an additional 1,000 the subsequent year. He’s also promised to clear parks of encampments, and while he’s avoided using the word “sweeps” he has backed the concept and did again at the Thursday presser.

“I just think that there has to be consequences for that kind of action,” Harrell said, referring to people who don’t accept the services or shelter they’re offered, Barnett reported, “because many people — and I’m very close to the world of people struggling with drug and alcohol treatment — people that have challenges, many of them are in denial. Many of them do not know what they need. They just do not.”

While insinuating homeless sweeps or at least other severe consequences for campers would ramp up under his administration, Harrell also insisted he wasn’t using a “dogwhistle” to appeal to advocates of homeless sweeps.

Going beyond the already optimistic CA29 schedule, Harrell has promised to speed up the timeline to six months for first 1,000 units, with the goal of having the full 2,000 units completed within the first year. One important caveat: instead of stating “emergency and affordable housing” as was written in CA29, Harrell has employed the term, “emergency, supportive housing” in his homelessness plan. Emergency housing typically refers to spaces like congregant shelters, hotels, and tiny house villages. Many homeless advocates had feared the passage of CA29 would result in funding being taken away from permanent affordable housing development in order to fund emergency housing. In order to achieve his ambitious emergency housing targets, Harrell would have to raise an impressive amount of outside revenue in order to avoid taking money away from the creation of permanent affordable housing.

Seattleites have heard similar bold pledges before: Mayor Jenny Durkan ran on a 1,000 tiny homes in her first year pledge to pair with a tough on homelessness and crime platform, criticizing Cary Moon for calling housing a human right, which she deemed expensive and idealistic. Durkan ended up building 73 tiny homes in her first year and still hasn’t met her pledge.

M. Lorena González, current city council president and Harrell’s opponent in the race, had expressed opposition to CA29 calling it deeply flawed, unconstitutional, unfunded mandate. González campaign manager Alex Koren said Harrell’s approach is cruel in a statement reported by KING 5: “Bruce Harrell outlined no serious plan today to pay for the shelter and services that are needed. He refuses to call on the wealthy and big corporations to pay their fair share to solve this problem because they are the ones who are bankrolling his campaign. Without funding, his promises of more shelter and more services are just more of the same empty promises we’ve heard for years.”

The González campaign said Harrell was using homeless people as political props.

“Harrell also cruelly suggested that we punish people for not going to shelter when our shelters are at capacity,” Koren’s campaign statement continued. “Punishing people experiencing homelessness for government’s failure to build adequate and available shelter and housing is wrong, though unsurprising from a candidate who routinely uses our unsheltered neighbors as political props.”

On her campaign website’s section devoted to the homelessness crisis, González has promoted her work as a co-sponsor of the JumpStart Seattle tax, which should raise about $153 million annually for affordable housing development. She also pledges to go further in raising new funding: “We can raise millions of dollars through a wealth tax at the city level, and I will work with our delegation in the state legislature to challenge and correct our upside-down tax laws.” CA29 took a different “no new funding” approach to addressing homelessness, with CA29 mastermind Tim Burgess pointing to Jumpstart (a tax he didn’t support) as a potential funding source for his measure.

These differences are also visible in the city council and city attorney races. In the tight city council race between progressive Nikkita Oliver, who opposed CA29, and centrist Sara Nelson, who approved of the proposed amendment, differing stances on how to address homelessness may sway voters’ support. This will also likely be the case in the starkly-contrasted City Attorney race between abolitionist Nicole Thomas-Kennedy and Republican Ann Davison. Incumbent Teresa Mosqueda, who opposed CA29, is also running against a supporter, Kenneth Wilson, but primary results suggests the race should fall in Mosqueda’s favor.

Even with CA29 out of the picture as a city charter amendment, some of its policies may live on depending on how Seattleites vote in November. And Compassion Seattle will likely live on as an independent expenditure arm of the Harrell and Nelson campaigns.

“The Compassion Seattle campaign cost more than a million dollars, funded mostly by dozens of large donations from a who’s-who of downtown real estate interests, as well as consultant Tim Ceis, who helped draft the measure,” Barnett reported. “Burgess gave just over $1,000 to the campaign.”

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.