The North Seattle Industrial Association is seeking to block Route 40 bus lanes and pedestrian upgrades citing expected freight delays.

Route 40 had the third most riders of any bus in the county pre-pandemic. Running from Downtown Seattle through South Lake Union to the Fremont Bridge, up Leary Way to the heart of Ballard, through Crown Hill, Greenwood and terminating at Northgate, the route is identified as one of seven priority corridors to upgrade to RapidRide-level of service by Seattle’s Transit Master Plan and the second-highest ranking corridor of those seven in terms of new ridership potential if those upgrades are made.

Unlike other transit corridor upgrades promised with the Move Seattle levy that have been significantly delayed and scaled-back, Route 40 is still mostly on track timing-wise. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is moving forward with speed and reliability upgrades slated in 2024 even if RapidRide branding — which include fancier red buses and stops with off-board payment — is on hold.

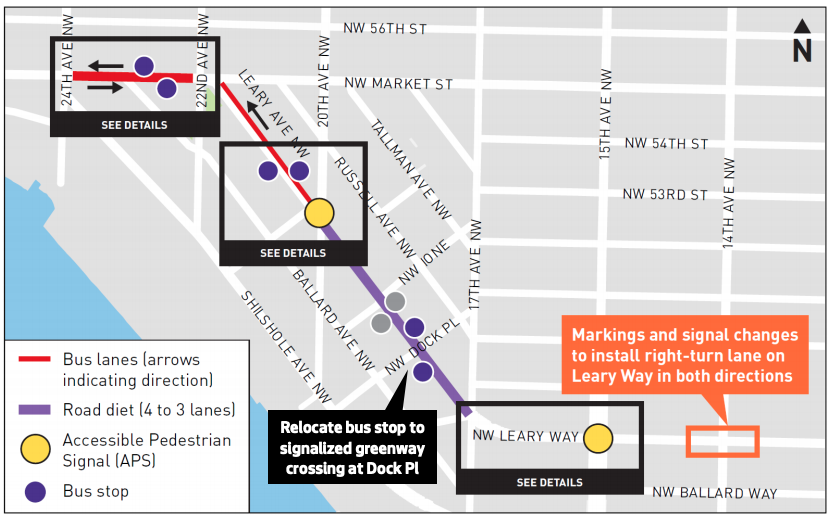

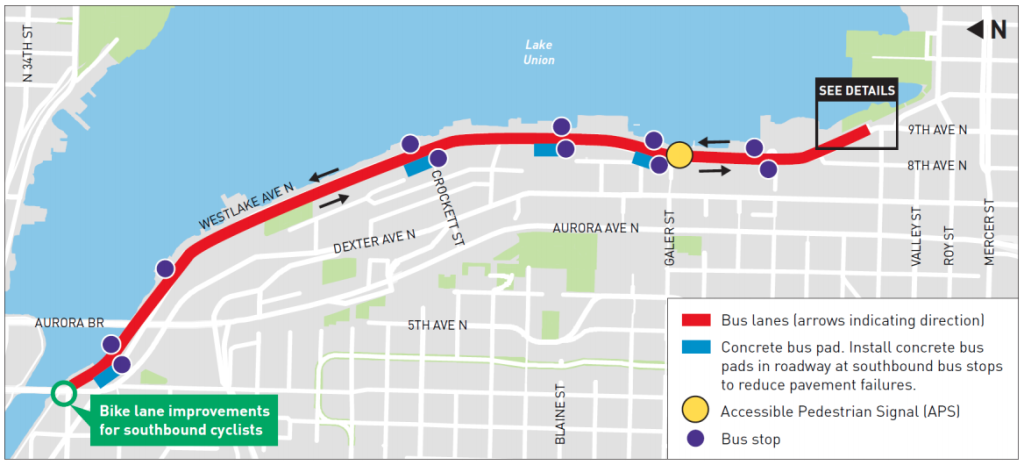

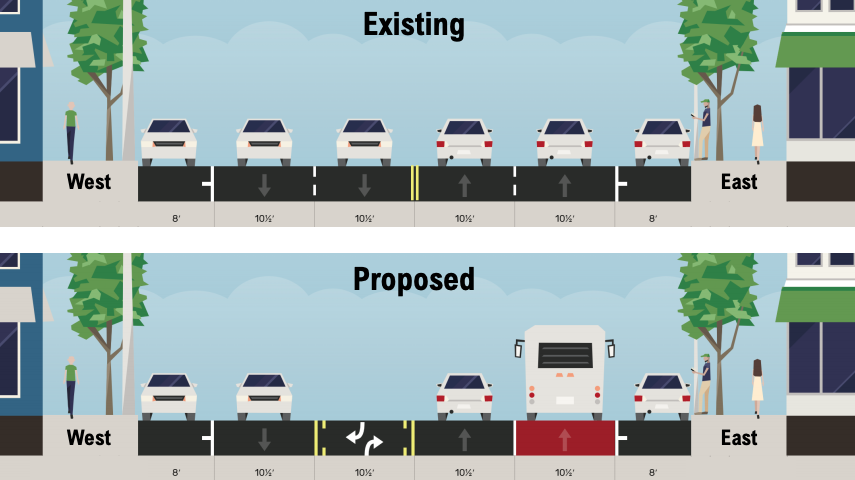

Earlier this year, SDOT shared early concepts for the corridor in advance of the project achieving 30% design, the point when plans would be available for the entire corridor. Included were proposed bus-only lanes: in both directions on Westlake Avenue N, NW Market Street, and on a short segment of Fremont Avenue N. Bus lanes in one direction of traffic were also proposed for N 36th Street (southbound) and Holman Road NW and NW Leary Avenue (northbound). Most of Leary Avenue in Ballard would not see bus lanes, but would get a rechannelization, going from four lanes to three wider lanes, one a center turn lane. The agency considered a bus lane on N 105th Street but opted against moving it forward due to limited right-of-way, according to SDOT.

As the project has moved forward, new emails obtained by The Urbanist signal behind-the-scenes pushback against the project from some business interests north of the ship canal. This past May, following a presentation on the latest plans provided by SDOT to the Seattle Freight Advisory Board and to the North Seattle Industrial Association (NSIA), Eugene Wasserman, the President of NSIA, sent an email to the Route 40 project manager and SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe.

“The North Seattle Industrial Association is requesting that the Seattle Department of Transportation restart the Route 40 Mulitmodel [sic] Project from the beginning,” he wrote. “The current project is totally flawed since you did not include freight as a mode to be part of the project. Your total disregard of freight issues and the improving the conditions for the maritime/industrial sector in Ballard/Fremont requires you to restart. The Route 40 runs on several Major Truck Streets. It appears to the Maritime/Industrial community that SDOT is willing to sacrifice the viability of maritime/industrial businesses and their employees so that Amazon workers can get to their offices 5 minutes earlier.“

That email followed an earlier one in late April where Wasserman outlined more specifically the problems with the project as seen by his side. “The major problem is the Project’s total lack of consideration of the impacts of the proposal on the Maritime/Industrial businesses in the BINMIC area. Of particular concern is the impact of the project on Leary Way and Westlake which are major freight routes. It is clear that the Project did not consider the impact particularly of the bus-only lanes on freight movement in the BINMIC. Removing the number of traffic lanes the project does will have a substantial impact on our maritime/industrial businesses and will assist in the increasing gentrification of our industrial area.”

From his position at NSIA, Wasserman has pushed back on transportation projects such as the Bicycle Master Plan, the Move Seattle Levy, and the Missing Link of the Burke Gilman Trail as one of the organizations in the coalition suing the City, the Ballard Alliance.

With the request for a restart in May, Mr. Wasserman included an 18-page report that NSIA commissioned from Claudia Hirschey, the same traffic engineer retained by the Ballard Coalition in its appeal against the Missing Link. It referenced a number of policy statements from various City documents, including the Comprehensive Plan, the Freight Master Plan, and Seattle’s Complete Streets ordinance. With each citation notes were included on how the policy could be interpreted to respond to freight mobility.

In one example, the report uses the fact that Seattle’s Pedestrian Master Plan doesn’t specifically include Leary Way NW as a corridor on its Priority Investment Network as justification for removing width from sidewalks allowing the street to be “reconfigured to provide for mixed-use pedestrian and bicycle facility or other designs and add width to travel lanes for truck mobility and safety on Leary Way NW.” In this way, the report can’t resist relitigating the Missing Link.

“The Route 40 corridor improvements preclude implementation of a bicycle facility on Leary Way NW. If the planned Burke-Gilman trail missing link on Shilshole Avenue NW is not be implemented due to lack of permits, (as well as truck mobility and safety issues) it should be recognized that the result is Ballard Way by default,” the NSIA report states.

An important aspect of the report is the idea that the changes made by the Route 40 project may not be acceptable even if they maintain current standards for freight mobility in the corridor. “The freight community would point out that the baseline analysis of 2015 [used in the Freight Master Plan] fails to acknowledge the significant impact to freight travel times and reliability in key freight corridors over the past 20 years. These impacts have occurred by increasing residential and employment density without improving infrastructure…Therefore, in project development, it may not be adequate to establish existing conditions as the baseline. A proposed project should be developed to improve truck mobility and safety for truck streets.” In other words, even in places where (for example) lane widths aren’t proposed to change with this project, if they are below the standard freight lane width of eleven feet they could be viewed as unacceptable.

SDOT Defends the Project

SDOT responded with a technical memo of their own on July 19th. Director Zimbawe’s letter in response that proceeded the memo noted where SDOT was at in the design process for the project. “As we approach the Route 40 Transit-Plus Multimodal Corridor (TPMC) 30% design milestone, we have followed our existing practices, policies, and procedures,” he wrote. “The Route 40 TPMC project is adhering to all adopted street design standards — including design standards that facilitate freight vehicle movements — to the greatest extent possible and documenting any deviations from those standards.”

SDOT’s memo notes that NSIA’s analysis left out the Transit Master Plan, which identified Route 40 as a priority corridor for investment. “There are several segments of the Route 40 corridor where the designated freight network overlaps with the frequent transit network. At the project level, we work within the existing policy to balance these sometimes conflicting recommendations,” the memo wrote.

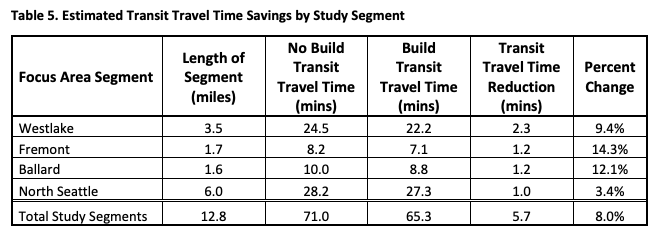

In conjunction with that response, SDOT has also produced a 310-page full traffic analysis, which was posted to the website for the project. The report shows an overall reduction in transit travel times over the length of the corridor of 8%, or nearly six minutes across all of the segments studied. Those travel time reductions are largest in Fremont and Ballard, but also significant along Westlake Avenue N where transit lanes are proposed in both directions. The report also notes that the slowest speeds on the corridor occur downtown, but that downtown is currently outside the scope of the study. Further downtown transit improvements that speed up buses downtown could improve Route 40 travel times even more.

The impacts to vehicles that aren’t buses are also detailed in the traffic analysis, with four intersections called out specifically as seeing a significant increase in queue lengths as a result of the project. During the morning peak hour, Fremont Place N / N 36th Street / Evanston Avenue N and NW 36th Street and 1st Avenue NW would see very long queues of traffic, per the report, with N 36th Street / Phinney Avenue N and the four-way intersection just south of the Fremont Bridge projected to see long queues during the afternoon peak hour. “As the project moves into design, design and/or operations modifications may be identified to reduce impacts to non-transit traffic,” the report notes.

Regarding idling emissions, the report includes an important caveat. “It should be noted, however, that the traffic analysis will not take into account changes to vehicle travel patterns or mode shifts induced by the proposed project. As a result, the analysis may over-report additional delay and/or vehicle idling increases at study intersections. Improvement to transit reliability, transit travel time, and non-motorized access to the Route 40 and other routes that share the corridor will make transit a more competitive mode choice compared to single occupancy vehicles (SOVs). A modal shift from SOVs to transit will help to reduce greenhouse gas emission, as well as potentially increase capacity for freight on the corridor.”

Undeterred NSIA Considering Appeal to Clean Air Agency

It doesn’t look like SDOT’s analysis has assuaged NSIA’s concerns. Eugene Wasserman, responding to a request from The Urbanist for comment, said NSIA stands by their request for a restart. “The project is worse than we thought after we received the information from SDOT. Our transportation consultant is currently going through the material.”

Reached via phone, he elaborated, saying that NSIA was considering asking the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency to intervene in the project on the grounds that idling traffic would negatively impact air quality. He called the project “seriously flawed” and said that it was not a “good public policy choice” to invest in a project for the “privileged.” He reiterated that transit improvements on Route 40 would only benefit Amazon workers in Crown Hill who could get to their offices five minutes sooner.

SDOT has yet to release full 30% designs for the project, which are complete. When asked how Wasserman and others have influenced the process so far, Ethan Bergerson of SDOT told me that “[t]he project team has been focused on the goals of the project which are to improve travel time and reliability of the Route 40. Because many segments of the Route 40 corridor are designated as major truck streets, maintaining freight mobility has also been a consideration when developing concepts. Feedback received from Wasserman, and other community members, prompted additional analysis to better understand and articulate if the proposed project will have any impacts on general-purpose and freight traffic.”

Bergerson said the additional requests for data from NSIA and others has not impacted the timeline of the project: the design portion of the project is expected to not be fully completed until 2023. “As we move into the design phase, we will work to ensure that truck movements at locations impacted by the project are adequately accommodated according to Streets Illustrated standards. We may identify additional steps to mitigate impacts to freight mobility during design.”

It remains to be seen if those steps will be enough to placate groups like the North Seattle Industrial Association who are pushing back on reallocating space for transit. We can likely expect the points of friction to persist up until the point of construction, if the dedicated space for transit isn’t walked back in the meantime.

Correction: An earlier version of this post mistakenly listed Eugene Wasserman as a past member of the Freight Advisory Board.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.