The numbers come from a new national report, but data from the City of Seattle also indicates a sustained decrease in housing production.

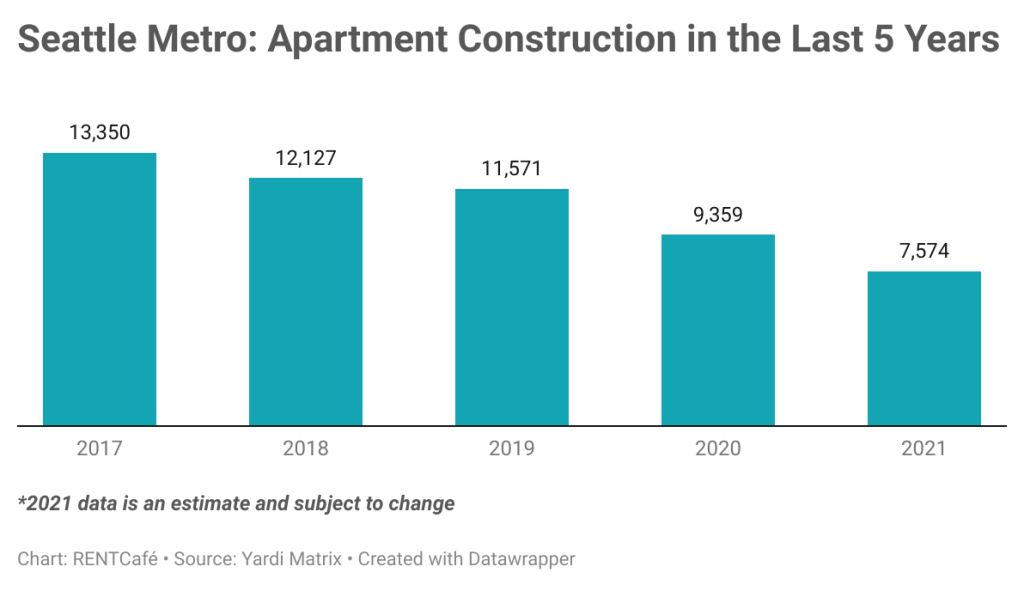

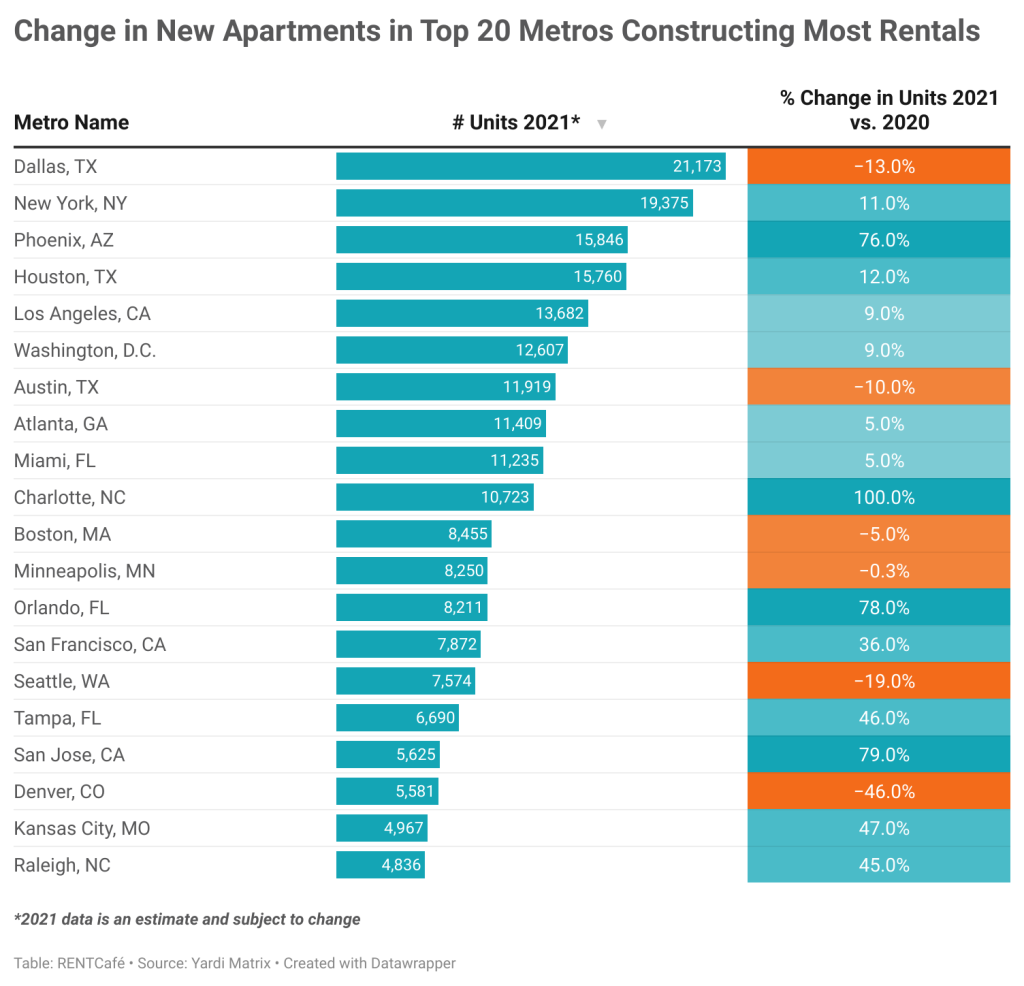

According to a recent report published by RENTCafé, apartment production in Seattle is down 19% when compared to 2020, with the number of projected new units set to reach a five-year low in 2021. Out of all 109 metro areas analyzed, Seattle recorded the second-largest decline in rates of apartment construction. The steepest decrease was exhibited in another metro also known for expensive housing costs and popularity with millennials, Denver, where new apartment production is projected to sink by 46%.

Nationally, new apartment construction is projected to be down by about 2.5% in 2021, with pandemic related slowdowns in permitting and financing, skilled worker shortages, and sky-high lumber prices all identified as factors contributing to the dip.

Metro areas that seem to be bucking the trend all seem to have one commonality: warm climates. Phoenix, Charlotte, Orlando, and San José, California are all projected to ramp up apartment production by 70% or more in 2021.

RENTcafé only tracks construction of apartment buildings with 50 or more units, so their report leaves out other forms of new housing, like small apartment buildings, triplexes, or single-family dwellings. However, data from the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) also points to housing production slowing in Seattle across different housing types, as does data from Commercial Analytics, “showing contractors in the first six months of 2021 began building only a handful of projects, totaling 523 units,” Puget Sound Business Journal‘s Marc Stiles reported. That slowing of construction starts could point to an even more abysmal 2022.

The slowdown in apartment production unfortunately is happening right as area rents are again climbing steeply. When the three-month bridge moratorium on evictions came into effect at the end of July, the statewide rent freeze ended and rents have been on the rise. Average rents were up a few percentage points in most Seattle neighborhoods, but they’re spiking even more dramatically in Tacoma (9.7%), Everett (8.8%), Bellevue (7.3%), and wide swathes of suburbia, Heidi Groover reported on August 12th. Tenants may be in for a tough year after the pandemic turmoil of 2020 led to the first drop in average rents in a decade.

A closer look at housing production in Seattle

First, a caveat. RENTcafé’s report assesses new apartment production for the entire Seattle metro area, so drawing comparisons between their report and data taken from the City of Seattle alone omits part of the region picture in housing growth. However, Seattle continues to be the regional leader in housing production, and SDCI’s data on housing production indicates clear trends on where things are tracking in 2021. Unfortunately, for people concerned about the regional housing shortage, the numbers are disconcerting.

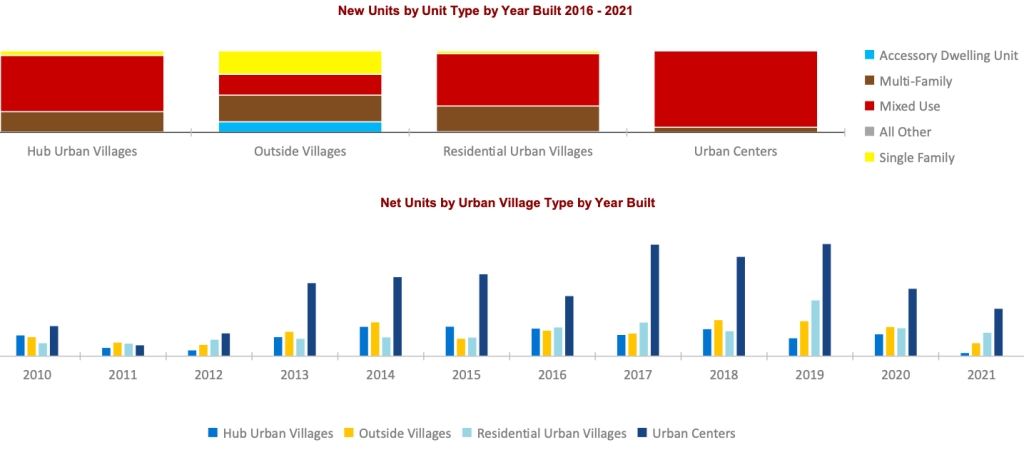

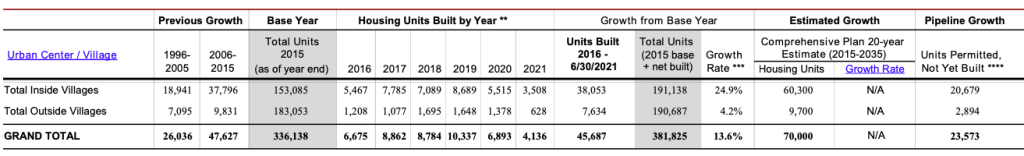

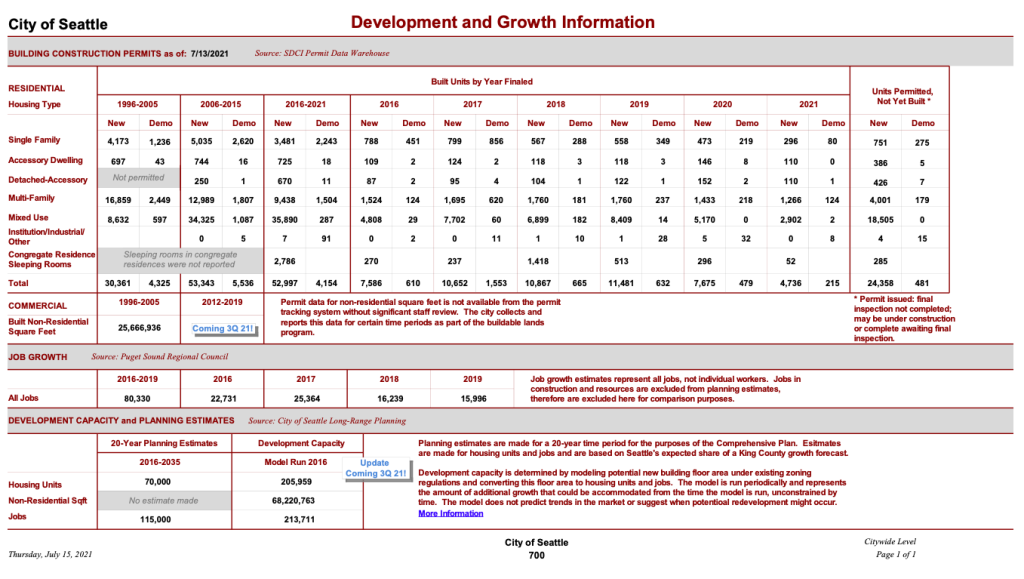

According to SDCI’s second quarterly report for 2021 (which tracks data up to July 15th), a total of 4,136 units of housing have been built thus far in the city, roughly 61% of the 6,893 housing units constructed during all of 2020.

Housing production peaked in Seattle in 2019 with 10,337 new units added, part of a trend of increased housing production that appears to have begun in 2016, but is now cooling off for its second consecutive year.

Since 2015, approximately a quarter of Seattle’s housing growth has occurred in its urban centers and villages, and this trend is on full display in the 2021 with 82% new housing units having been constructed inside urban centers or villages. The largest concentration of new housing (2,223 units) was added to Seattle’s urban centers, a zoning designation that applies to the neighborhoods of Downtown, South Lake Union, Uptown (Lower Queen Anne), Capitol Hill, the University District, and Northgate. Overall, urban centers appear to be on track to maintain a similar rate of growth between 2020 and 2021.

On the flip side, SDCI’s data reveals a sharp decrease in new housing production in hub urban villages, a planning designation that applies to Ballard, Fremont, Mount Baker, West Seattle Junction, Lake City, and Bitter Lake and connotes greater residential and job density than urban villages of the non-hub variety. Only 172 new housing units have been built in hub urban villages so far in 2021, according to SDCI. To put those figures in context, in 2020, 1,041 new housing units were constructed in hub urban villages.

While it is possible that the second two quarters of the year may reveal in uptick in housing production in hub urban villages, such a dramatic decline raises important questions about how much future growth can be accommodated in these areas of the city. Since they comprise only six neighborhoods, developable land in hub urban villages may be running low — it may be wise to expand their borders or add more hubs elsewhere given the regionwide slowdown.

The data for residential urban villages, examples of which include Columbia City, Eastlake, Roosevelt, North Beacon Hill, and Wallingford, does tell a different story. 1,111 new housing units have been logged so far in 2021 in residential urban villages, roughly 84% of the 1,320 units constructed in all of 2020. However, residential urban villages are generally zoned for lower density than urban centers or urban hub villages limiting how much new housing capacity can be added to these areas.

Existing zoning ordinances hinder housing growth and exacerbate racial inequities

Despite proclamations to the contrary, Seattle continues to grow in jobs and new residents. In 2019, the last year for which job statistics are available, Seattle’s economy added approximately 15,996 new jobs — yet, by SDCI’s estimate only 10,849 new housing units were constructed that same year. Years of population and job growth outpacing housing supply has led to the city suffering from some of highest housing costs in the nation. Zoning ordinances that continue to emphasize exclusionary zoning, which restricts the construction of multifamily housing to less than a quarter of the city’s developable land, have exacerbated the situation — and reaped negative consequences for the state of racial equity in housing and wealth accumulation in Seattle.

Published earlier this summer, the racial equity toolkit analysis of Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan by Policylink was clear about the negative impact Seattle’s zoning ordinances have had in this regard. Funneling growth into urban centers and villages has forced low-income Seattleites, in particular residents who are BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) to complete for limited affordable housing opportunities, which will only continue to grow scarcer if housing production continues to slow.

Unfortunately, the exclusionary zoning story is very similar regionwide, with single-family zoning consuming the majority of residential land and opportunities for apartment construction very limited and often shoehorned near freeways. Moreover, high demand cities like Bellevue and Kirkland have emphasized office growth over residential growth. As rent growth is stronger in the suburbs than in Seattle and light rail will soon reach Bellevue and Redmond (2023) and Shoreline, Mountlake Terrace, Lynnwood, Kent, Des Moines, and Federal Way (2024), now would be an ideal time for those cities to step up to the plate.

Overall, while it is true that a variety of factors have contributed to the decline in new housing construction in Seattle, there is an argument to be made that City’s current zoning ordinances are hindering the development of new housing to a disastrous effect. By focusing on the production of large apartment buildings, RENTCafé’s report might only offer a snapshot of housing growth in the Seattle metro area, yet it is still glimpse of an ugly reality supported by other data — as the need for housing continues to grow, fewer units of housing are being constructed in Seattle.

This post was updated to remove inaccurate information related to the Washington State eviction moratorium. A bridge moratorium went into effect at the end of July which expires at the end of September. It does not contain the same protections for renters as the previous moratorium.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.