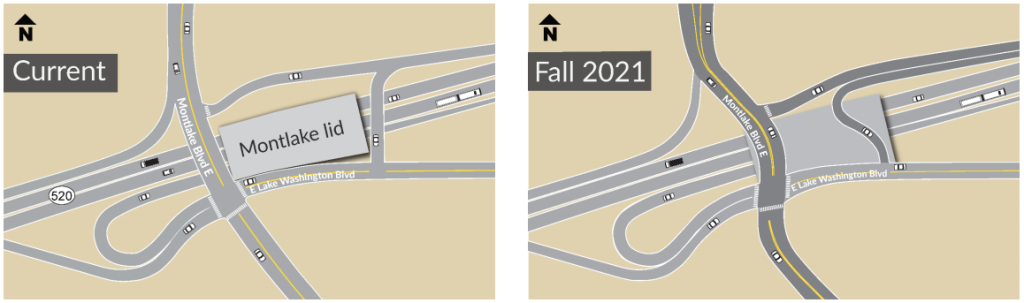

This coming weekend Montlake Boulevard over SR-520 will be completely closed between Roanoke and Hamlin Streets so that the entire roadway can be shifted east onto what will become the Montlake open space lid. The change will allow for crews to extend the lid structure to the west, making space for the newly rebuilt Montlake Boulevard.

With the Montlake drawbridge closed to vehicle traffic until the morning of Friday, September 3rd, this closure will not be as impactful as it otherwise would be, and people biking and rolling will still be able to access the entire Montlake Boulevard corridor as usual. However, the work accomplished this weekend marks a pivotal point in the overall 520 replacement project in Montlake and also provides a valuable chance to look back on how we arrived at this point.

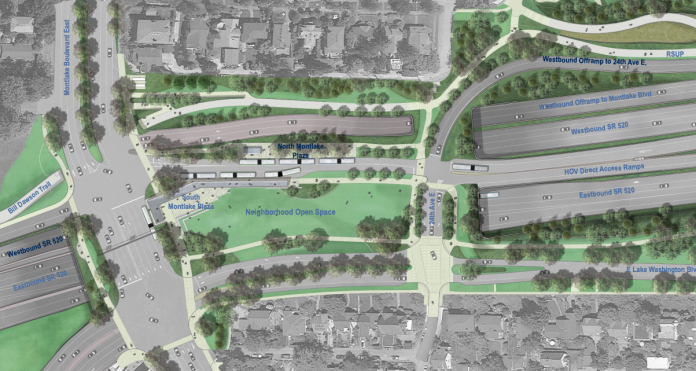

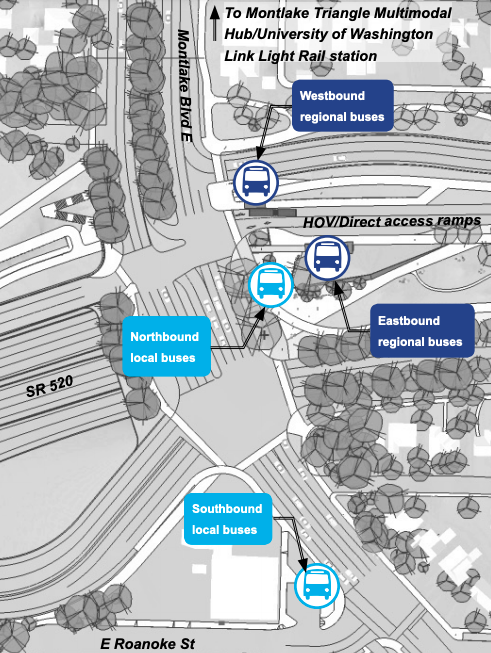

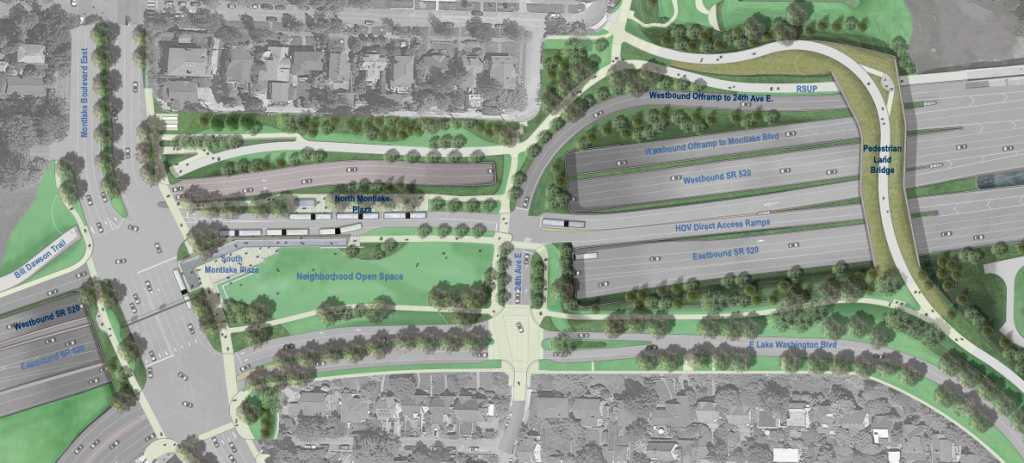

By next year, a new Montlake Boulevard will fully take shape where the current one stands, but with nine motor vehicle lanes directly over 520 in comparison to the six that existed prior to the start of construction. Two lanes in each direction will be through lanes, while four of the additional lanes will all be turn lanes, including a southbound left and right turn lane and two northbound left turn lanes. The remaining northbound lane will be dedicated to transit and paired with a direct transit connection on the Montlake lid, although with no southbound transit lane counterpart. The northbound bus-only lane will continue a bit north of 520, according to project plans, stopping in advance of the Montlake drawbridge.

To accommodate all of the turning movements directly over 520, the southbound bus stop along Montlake will end up down at Roanoke Street in contrast to the direct connection to 520 buses that will be available to northbound riders.

How did we end up with a nine-lane Montlake Boulevard?

Like so many road expansion projects, the answer to why Montlake over 520 was expanded into nine lanes is partly attributable to bunk traffic volume forecasts.

The traffic analysis, conducted for the 520 replacement project’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) in 2011, used data showing a 15% increase in traffic by 2030 at the Montlake interchange during the morning peak period and a 21% increase during the afternoon peak period. According to that EIS, if no changes were made, the eastbound ramps at 520 and Montlake Boulevard would see so much traffic that they would end up 50% over their designed capacity, compared to only 15% over their designed capacity with the highway expansion. Whew, disaster averted.

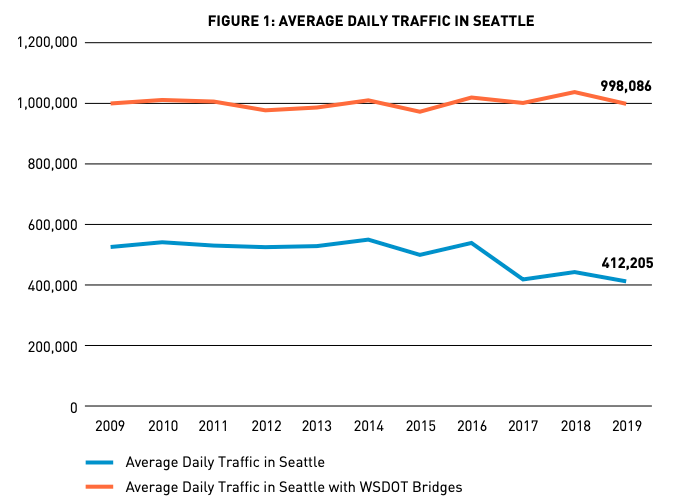

The EIS cites a 2006 report from the Puget Sound Regional Council that “the region” would “need to accommodate close to 40 percent more traffic” by 2030, a fact that only seems relevant in retrospect for how wrong it now appears to be, at least in Seattle. Average daily traffic volumes in the city have been almost completely flat since that report was put out, even declining a bit when the biggest sources of traffic, the state-controlled bridges like SR-520, were not included in the yearly counts, as shown below.

In an effort to advocate for more dedicated transit in the Montlake Boulevard corridor, the Seattle City Council went on record in 2010. “Dedicated HOV/transit lanes should be provided on Montlake Boulevard…WSDOT should also commit to working with SDOT to consider extending the dedicated HOV/transit lanes on Montlake Boulevard to the north, and on 23rd Avenue to the south. The southern corridor should be reviewed as far south as the intersection of Madison and 23rd Avenues,” noted a letter submitted as part of the EIS process and signed by all nine councilmembers at the time. But the Durkan administration missed a more recent opportunity to add bus-only lanes to the 23rd Avenue corridor as part of a recent rechannelization, or road diet, on that street, and the Route 48 “transit plus multi-modal corridor project” along that street has the smallest planned budget of any transit corridor improvements moving forward, only a little over $2 million. The 520 project was clearly a missed opportunity for improving transit access through the corridor.

Of course, the four-lane Montlake drawbridge will remain a pinch point for transit for the foreseeable future, with dedicated transit lanes on that bridge a nearly impossible lift. The 520 project actually plans a second bascule bridge over the Montlake Cut, something that the City of Seattle has never supported: not in 2010 when the city council commented on the EIS, and not in 2019 when interim Councilmember Abel Pacheco tried to introduce a resolution supporting a new bridge if the added capacity went to transit, bicycle, and pedestrian space. That resolution went nowhere, with then-transportation committee chair Mike O’Brien making clear he did not support adding any new roadways.

Recent comments by State Senator Jamie Pedersen, who represents the district where the new bridge would be built, suggest that the state may seek to reallocate funding for that second bascule bridge to other projects given the lack of political will to push that project forward without city support. The second bascule bridge may be dead, but the added road capacity over 520 will remain.

New pedestrian and bike connections will improve mobility in the corridor

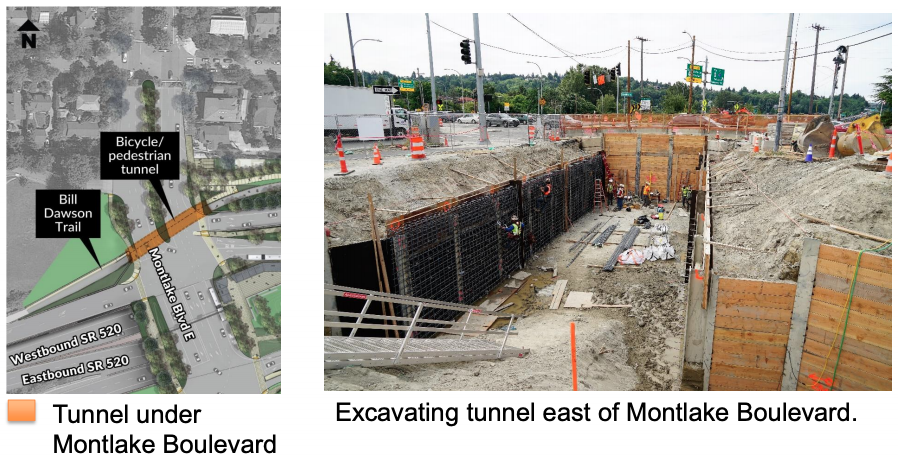

Another part of the project happening right now is excavation work to create a tunnel under Montlake Boulevard just north of 520 that will enable the Bill Dawson Trail, which connects to Montlake and enables people walking and biking to avoid most of the 520 ramps, to eventually connect directly with the Montlake lid and the shared-use path across the lake.

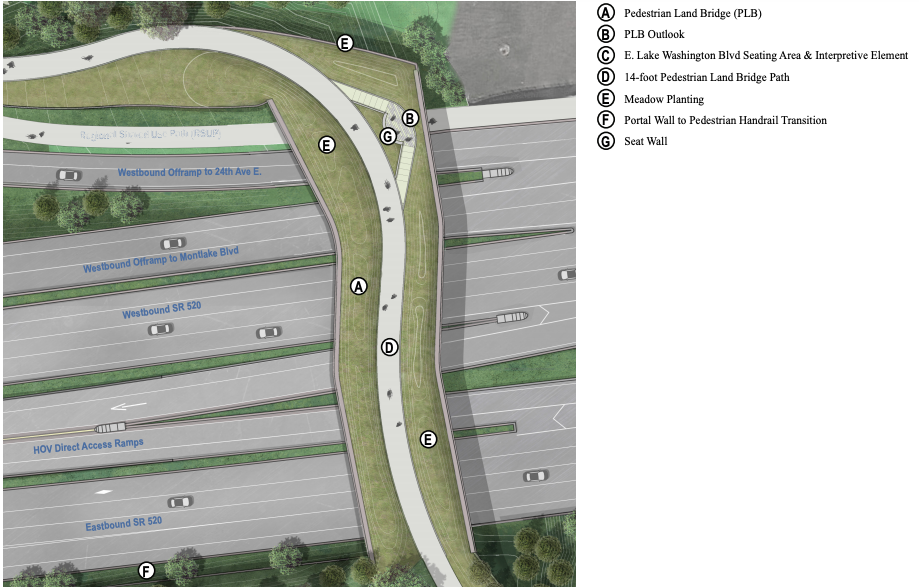

The pathway will also connect directly with the planned “land bridge” (i.e., pedestrian and bike overpass) overlooking Union Bay on the east end of Montlake, taking the place of the temporary underpass on that end of the 520 project that is currently in place during construction.

The bike and pedestrian overpass is a result of the Montlake lid being scaled back dramatically compared to the original concepts for the lid. A 1,400 foot lid was originally envisioned in Montlake, but after working with the Seattle Design Commission, an 800 foot lid moved forward that removed “areas of the lid that would have had poor public access and would not have met the project goals of providing safe public space,” according to WSDOT’s update to the EIS. The larger lid would have necessitated ventilation structures and an operations and maintenance facility, which would have themselves taken up space on the lid itself. The coming “land bridge” will be the best connection for people on bikes to connect from the Washington Arboretum up into Montlake. Unlike a normal overpass, it is being built with heavy landscaping and overlook features that will make it function a little more like a freeway lid.

The entire Montlake project is expected to wrap up by 2023. The bike and pedestrian connections, many of which have not really existed before, are going to significantly improve mobility through the area. But rebuilding nine lanes of Montlake Boulevard over 520 really illustrates the degree to which this megaproject reflects an outdated mode of thinking in which Seattle needs to accommodate more and more vehicle traffic. It also reflects a missed opportunity to fully plan around transit, and not only accommodate it as a side project.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.