Yesterday, the Seattle Community Police Commission (CPC) announced that Bruce Harrell had declined their invitation to a mayoral candidate forum on police accountability and public safety, leading them to cancel the event. Both leading candidates are promising to increase police accountability and reduce incidents of racial bias and excessive force, but their methods vary significantly.

Former Council President Bruce Harrell finished first in the August Primary with 34% of the vote, but Council President Lorena González was close on his heels with 32.1%. The two will square off in the General Election and some of the issues where they are contrasting the most include homelessness, policing, and corporate power. Harrell is passing on this opportunity to make the contrast at a forum hosted by the city’s official civilian voice on police matters.

“Police accountability and public safety are amongst the most critical issues in the city. I agreed to participate in the Community Police Commission mayoral forum because it would have been a meaningful opportunity to engage with voters on these topics and it is a shame that voters will not get that chance,” González said via email. “I plan to continue making these issues a central focus of my campaign.”

Harrell ally Tim Burgess made a similar contrast case in an endorsement and fundraising pitch for the Harrell campaign: “[T]heir visions for Seattle’s future are incredibly different, most significantly regarding homelessness, policing, and their perspective of our job-creating businesses.” The irony likely wasn’t lost on the González campaign. The side claiming the high ground on policing was passing on the opportunity to engage voters on it.

Burgess, who cultivated a Mr. Nice Guy persona before retiring from Council and moving on to running political hit pieces against former colleagues with a well-funded political action committee he set up, proceeded to aggressively go after his former colleague González while misspelling her name.

Going negative on González

“Gonzalez envisions a city with a dramatically reduced police force that pursues only the most serious crimes, leaving many misdemeanors, including property crime, unchecked,” he wrote. “She has no real plan to bring those living unsheltered inside or stem the proliferation of tent encampments in our parks and on our sidewalks and says if elected she will continue the current approaches of the City Council. She’s actively hostile to the downtown businesses that pay the bulk of taxes that fund city services. She promises to abolish all single-family neighborhoods, an astonishingly blunt action that will only create years of legal and political squabbling.”

Setting aside Burgess’ Trump-style “abolish the suburbs” fearmongering for now, of course, the former cop and Seattle Police Department (SPD) PR guy, trots out the familiar campaign trope of rising crime and scary unrest, as the Harrell camp did in the Primary. Between Burgess’ harangues and Harrell skipping the CPC forum suggests there will be no statesmen-like pivot to soberly debating public safety solutions rather than focusing on fearmongering about crime and not enough respect for police. Instead, every issue of public safety and policing is presented sensationally and laid at González’s feet.

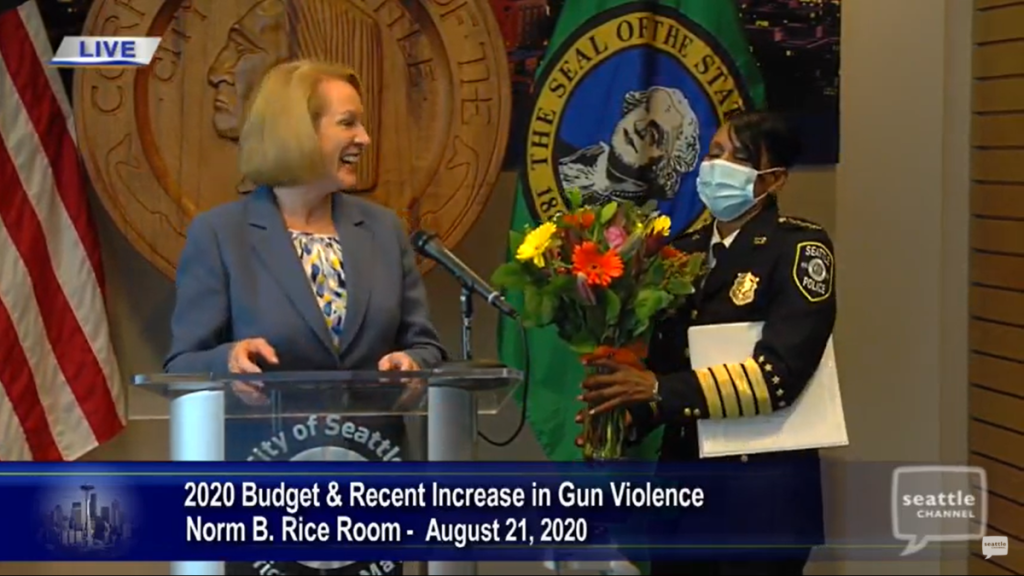

“She allowed the debate over policing to become so antagonistic, so disrespectful of the women and men who serve our city, that the police chief — the first Black woman to lead our officers — resigned in protest,” Burgess wrote.

The Urbanist has covered how Carmen Best’s reasons for resigning were much more complicated than mere disrespect. For one, she was being asked to weed out officers who were particularly dishonest, violent, and bad at their jobs and bristled at that approach, instead backing the police guild position that firings shouldn’t happen and that they would need to happen in order: last in, first out. The Council urged Best to fire officers with a history of misconduct and use a provision allowing her to break from the hiring order, but she resisted, citing the high amount of paperwork and appeal process it required.

Beyond being asked to clean house of her worst officers, Chief Best was dealing with an extremist police guild president and insubordinate commanders undermining her authority, including one who abandoned East Precinct without an order from her or Mayor Durkan (who skipped the relevant meeting). The full gravity of that issue was hidden for a year after Mayor Durkan, Chief Best, and four other senior SPD command staff orchestrated a coverup illegally deleting months of text messages. Surely, being undermined by her insubordinates and used as a political shield by a floundering mayor wasn’t an ideal job situation. She went about blaming the Seattle City Council, which didn’t create those particular issues, as an easy way out.

“The Gonzalez approach to policing creates unnecessary risk at a time when violent crime has surged to the highest it’s been in the past ten years, a documented increase comparing the January-July period each year between 2012 and 2021,” Burgess wrote. “On the other hand, Bruce Harrell seeks reform without risking public safety or demonizing the many officers who serve our city with professionalism and integrity, treating all people with dignity. Harrell understands safe neighborhoods are essential for shared prosperity. He appreciates the vital work of our police officers and isn’t afraid to say so.”

If only police reform was as simple as Seattleites being nice to police officers to earn their good behavior, then the Harrell-Burgess plan might get us somewhere. But let’s be honest, we know their police reform approach track record because each had three terms, including stints for each as public safety chair, and they didn’t make headway.

The intertwined careers of Harrell and Burgess

Burgess’ new role as Harrell’s attack dog isn’t a total surprise. Harrell and Burgess’s careers are very intertwined and many of their positions were similar.

Both men were first elected to Council in 2007. Both men ran for mayor in 2013, but exited the race after Murray got in and then ultimately endorsed Murray — for Burgess, this was despite Murray poaching his political consultant, the highly sought-after centrist campaign whisperer Christian Sinderman. Both men sparred with Murray’s predecessor, Mayor Mike McGinn, and helped to stonewall his agenda including Consent Decree-driven police reform efforts, laying the groundwork for ousting him. Both men initially defended Mayor Murray in 2017 after numerous sexual abuse allegations surfaced, but turned on him after it was clear he was a political goner and they could be interim mayor.

“I’m not asking him to step down,” Harrell told reporters in July, adding Seattle residents “did not ask us to judge anyone for something that happened 33 years ago or maybe didn’t happen. We just don’t know. And I would ask that I don’t want to be judged for anything 33 years ago…. And I would challenge each of you to think about where you were 33 years ago. The question is are you doing your job today right now?” Similarly, Durkan accepted Murray’s endorsement in late June before later disavowing it as more allegations arose.

In contrast, Councilmember González led the charge on Council to encourage Murray’s resignation and take allegations seriously rather than immediately discredit them. “As a dogged advocate for sexual abuse survivors, I take these administrative findings very seriously, and they raise grave concerns,” she said. However, because removing Murray would take six votes and Harrell, Burgess, Debora Juarez, Sally Bagshaw, and Lisa Herbold opposed the move, the effort stagnated. Because of that, Murray survived in office until September, after a fifth victim came forward and went public with a signed declaration of Murray’s abuses.

Harrell was City Council President in 2017 when Mayor Ed Murray resigned due to his sexual abuse scandal. The City Charter gave the Council President first dibs to be interim mayor until the next election, but Harrell only kept the role for five days before passing the honor to his colleague Burgess, who served for 71 days until the results of the next election were certified. Both men endorsed the winner of the election: Jenny Durkan. Fast forward four years and Harrell largely followed Durkan’s playbook and reunited the same homeowning coastal coalition to Primary victory.

Abolish the suburbs pearl clutching

Burgess also chose to make zoning policy a major area of attack on González. This is an area where he may not be on as solid ground as he thinks. After all, Bruce Harrell doesn’t have a housing plan on his website, nor has he really articulated one on the trail. Beyond outsourcing an emergency shelter plan to the Compassion Seattle ballot measure, he lacks a platform to address housing affordability and creating more housing at all income levels.

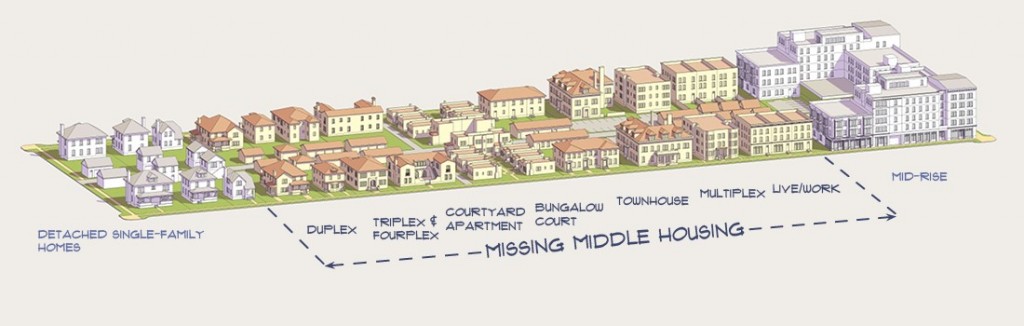

In contrast, González’s housing platform is refreshingly direct and to the point: “End exclusionary zoning that makes our neighborhoods sprawl, increasing reliance on driving and causing congestion. Increase mixed use zoning that allows more corner stores, coffee shops and other neighborhood amenities within walking distance, making extra car trips unnecessary. We need policy to support this — that means zoning that encourages complete communities, and a permitting process that preserves community voice but prevents obstructionism.”

González brings up the concepts of missing middle housing and 15-minute cities frequently to underscore the climate and livability benefits of zoning reform and urbanization. She repeatedly voted to increase the scope of Mandatory Housing Affordability rezones rather than scale them back, as Councilmember Harrell did in his district. He managed to drop some areas from affordability requirements.

The Urbanist Elections Committee questionnaire took special effort to ferret out candidate positions on housing and zoning, but Harrell’s responses evaded our efforts and stayed vague and noncommittal. Asked whether he’d rezone wealthy White neighborhoods like Madison Valley, Laurelhurst, Montlake (where access to opportunity is high and displacement risk is low), Harrell said he agreed with smart growth but that “the wealth or lack of wealth of the neighborhood should not be the determinative factor.” In practice, the City ignoring wealth as a factor has meant that the wealthiest neighborhoods have largely avoided upzones and affordable housing development.

Tim Burgess, who lives in a $1.2 million condo in Queen Anne, chaired the Queen Anne Community Council (QACC) in the 1990s — a time when neighborhood groups across Seattle were coming up with neighborhood plans that set the zoning as part of Seattle’s 1994 Comprehensive Plan required by the Growth Management Act passed by the state legislature a few years earlier. The City’s plan aimed to designate a smattering of urban villages across the city where growth would be focused while leaving the rest of the city a sea of single-family zoning and other non-residential uses. Of Seattle’s 84 square miles of land, about 10 square miles were urban villages and centers where dense housing, offices, and retail could go. Roughly 30 square miles were set aside as detached single-family zoning, where a new duplex or triplex couldn’t be built even if plenty of historic “grandfathered in” examples were already there.

A historic site of apartment density, the City wanted to tap Queen Anne as an urban village. The QACC succeeded in shrinking the urban village contours significantly, so the top of the hill has seen minimal growth in the ensuing decades, just as former Councilmember Jim Street predicted as he reassured a wary QACC. Other rich neighborhoods like Magnolia, Laurelhurst, and Madison Park succeeded in getting themselves removed from urban village plans entirely. Burgess’s view corridor condominium has accrued considerable value as housing has grown scarcer and the city has grown wealthier, which perhaps reveals why he doesn’t see the need for dramatic changes and instead is trying to rile up homeowners like himself to fight them. Likewise, Harrell owns a multi-million-dollar home in Seward Park and long held a second home, a condo in Downtown Bellevue that he portrayed as an investment property rather than a residence. He sold the condo before running for mayor this year.

“As for housing, on primary election night, Gonzalez said she would abolish all single-family zoning in Seattle,” Burgess wrote. Consider the implications if you live in Beacon Hill, Rainier Valley, West Seattle, Lake City, Greenwood, Ballard, Wallingford, or Fremont. Gonzalez would rezone all these neighborhoods — and many more — to allow large multi-family apartment buildings, triplexes, duplexes, and condominiums. Her primary election night statement was consistent with the answer she gave The Seattle Times in late June; when asked if she would eliminate all single-family zoning, she answered ‘yes.'”

Burgess does shed some light on what Harrell’s housing strategy might be, which is largely more of the same strategy of focusing housing growth on busy polluted thoroughfares to shield leafy suburban neighborhoods from change.

“Harrell understands the significance and complexity of Seattle’s housing supply shortage yet doesn’t believe the answer is to completely wipe out single-family neighborhoods. He favors increased density where it makes sense, for example, along major transit corridors and arterials, including those in single-family zones,” Burgess wrote. “As for leadership style, Gonzalez has allowed the politics of exclusion to dominate, the ‘us versus them’ approach of confrontation and denigration of opponents. It’s an approach largely responsible for the City Council’s paralysis and dysfunctionality on so many issues and the public’s appallingly poor perception of the Council.”

The reality is that 70% of Seattle’s population lived within a 10-minute walk of very frequent bus services (10-minute all day service) as of 2019. That means that the idea that wide swaths of Seattle aren’t suitable for transit-oriented development isn’t borne out by the facts. The conversation isn’t just about dense apartment buildings, but also missing middle housing types like fourplexes that need not be restricted to only frequent transit corridors. Plus, we would expect visionary climate leaders to be solving the gaps in transit service where they exist rather than using them as an excuse to keep exclusionary zoning and lock in million-dollar homes.

In Burgess’ world, issuing a short paragraph of compliments — she’s intelligent, committed to public service, cares deeply, and is politically progressive — which also makes clear Harrell has all those qualities too in greater measure is enough to qualify as a friendly non-confrontational approach even though everything in the piece is dripping in disdain and loaded with aggressive political attacks of varying veracity. For example, ending exclusionary zoning hardly equals “abolishing” or “completely wiping out single-family neighborhoods” — a neighborhood will still be alive and well when a triplex or courtyard apartment goes in a few doors down. Why still pretend to be Mr. Nice Guy when he’s settling exclusively into the ‘get off my lawn’ attack dog role? Perhaps, old habits die hard. And why do people like Burgess descend into a rage at the thought of houses touching and apartments commingling with his precious suburbia? Perhaps because tenants are always assumed to be the nuisance, and homeowners God’s gift to Seattle? It’s a mystery. One doesn’t see tenants going around losing their heads like this and getting so nasty when a new single-family home goes up and a wealthy family moves in next door.

Whether sprinkled with a few compliments or not, Burgess’ fiery hit piece has hit on some of the key issues of the race between angry barbs. Do we trust police reform, public safety, climate action, housing affordability, and homelessness to the same faltering approaches and leaders of decades past? Or do we forge ahead with a more progressive vision bold enough to question the assumptions of the past? Who do we put first in crafting policy: the well-heeled homeowners on top of the hill who have always gotten their way or the rent-burdened masses at the bottom who sorely need a break?

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.