Americans typically associate the kind of accessibility offered by 15-minute cities with European metropoles, but with smart planning 15-minute cities can thrive in the United States too.

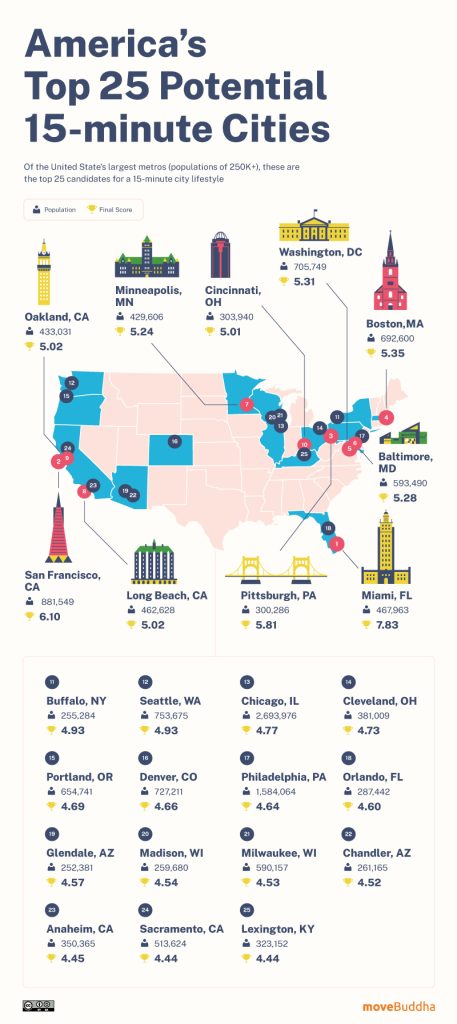

Step aside, New York and Los Angeles. According to a newly published study by moveBuddha, mid-size American cities of 250,000 to 750,000 residents dominated the rankings of the top 25 future 15-minute cities in the United States, with a few large cities known for engaging in urban planning on the neighborhood level, for instance Chicago and Philadelphia, also making the cut.

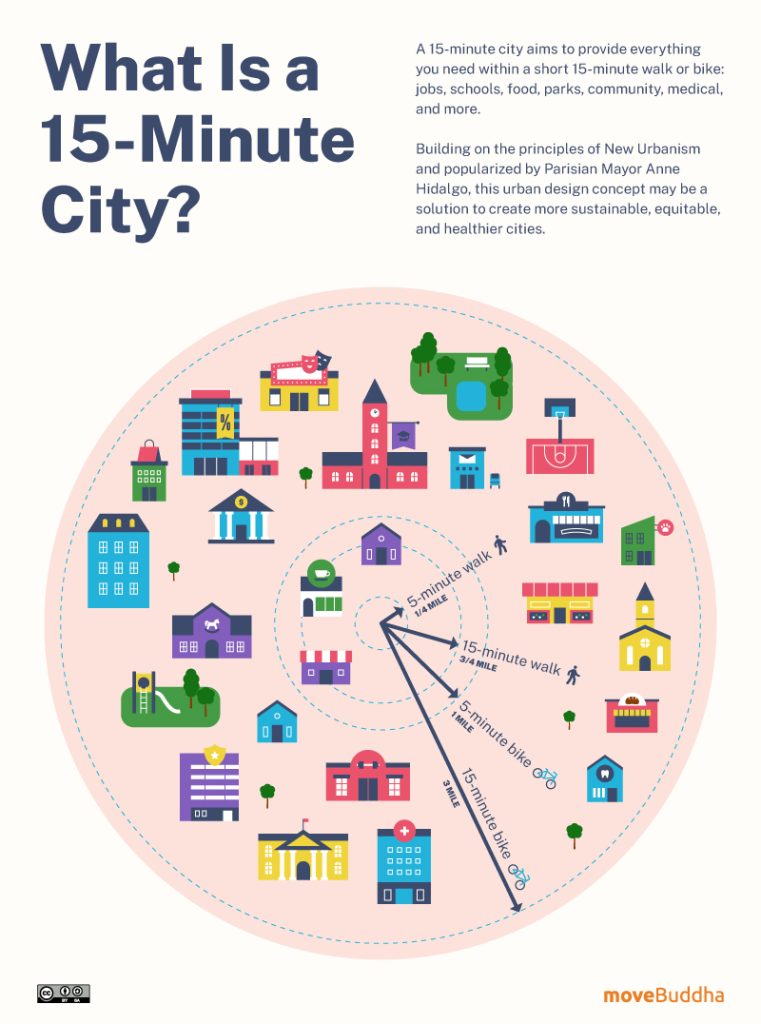

The idea that residents should be able to meet their basic needs within a short walk or roll of their home was popularized by Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris, early on in the Covid pandemic, and it has been met with widespread enthusiasm among urban planners and policymakers the world over, including in sprawling North America. If we are lucky, the 15-minute city might revolutionize planning of the 21st century to the same degree that Le Corbusier’s concept of the tower and car-centric radiant city did in the 20th century. Urban planners have begun to theorize on what ten-minute cities and even five-minute cities might look like as well.

But before we get carried away with visions of a five-minute city, a title which tiny Whittier, Alaska, a town of 200 residents who live under the same roof might be among the few to lay claim to, let’s examine closer what it means to be a 15-minute city.

What criteria were measured by the study?

To calculate its data, moveBuddha collected and assessed data from the 78 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. To generate its scores, study author Joe Robison used walking and biking scores assigned to cities by Walkscore.com; it also takes into consideration a variety of additional factors using publicly available data (often via Google Places API) that included:

- Labor force participation;

- Number of social associations;

- Food environment index (determines level of access to healthy foods);

- Access to exercise opportunity;

- Density of health and safety providers (hospitals, emergency medical services, mental health providers, primary care physicians, nursing homes, fire stations, and local law enforcement);

- Severe housing problem index (measures overcrowding and properties in urgent need of repair); and

- Housing to income ratio.

Using this data, cities were each assigned point scores of 1 to 10 (10 being the best) in five areas that included commutability, social and physical health, childcare/education, medical and safety, and home affordability. These area scores were then compiled together into a general score. As a company focused on selling long-distance moving services, moveBuddha does have an interest in encouraging people to pack up and head for a more enticing city. Still, even if it the study uses rather blunt metrics and may have an agenda, it’s still an interesting snapshot and discussion starter.

One decision made by the creators of the study that could be considered controversial was to exclude destinations that could be accessed by transit. The decision was based on guidance from the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU), which has decided to omit transit from its definition of a 15-minute city. Still, it seems odd to ignore access to transit when assessing the 15-minute city, since most of us would want to head out of even the most utopian 15-minute city from time to time.

The case could be made to include or exclude certain criteria as well. For example, I would like to see access to veterinarians added to the list. Moreover, some criteria could be parsed differently. For example, some residents — particularly those who experienced police harassment and racial profiling — would view density of local law enforcement as a risk to their health and public safety rather than boosting it.

Which cities were identified as future 15-minute cities?

Miami topped the rankings this year with a total score of 7.83. San Francisco came in second, with a total score of 6.10. San Francisco’s score was negatively impacted by lack of access to childcare (2.3), a common problem in many high ranking cities in the list, including Boston, which earned a dismal score of 0.4 in this area.

According to the makers of the study, Miami earned its number one spot as a result of plans to create small, walkable urban centers throughout the city bearing fruit. The Miami Herald has called Miami “a city of interconnected villages,” and ambitious projects like the Underline, which is repurposing land under its Metrorail elevated transit lines into a ten-mile linear park and trail, are increasing safe walking and rolling options for residents. All of this sounds like a far cry from the city I remember walking and riding transit through when I last visited Miami about 14 years ago so it’s encouraging to learn of these improvements. Granted, the decision to exclude transit quality as a metric likely boosted Miami’s score; the city has been bleeding bus ridership over the past decade.

However, housing affordability emerged as a major issue among nearly all cities that made the list, with Miami (2.9) and San Francisco (3.3) certainly included. Overall, six of the top ten cities listed had home affordability scores lower than 5 (out of 10). Looking more broadly, the least affordable city on the top 25 list was Long Beach, California (2.7) while the most affordable was Pittsburgh (7.3).

What scores did Seattle and Portland earn?

The Pacific Northwest cities of Seattle and Portland were identified by the study as cities actively engaged in planning to become 15-minute cities; however, each city needs to make improvements in key areas to meet that goal.

Seattle, which landed at 12th place in the top 25 list, scored well for its walk and bike score (8.1) and dining, parks, and community score (7.3); however, scores for childcare (2.3), health and safety (2.6), and housing affordability (4.5) were all significantly lower.

Portland was placed at 15th on the list and exhibited strengths and weaknesses similar to those of Seattle. Earning an impressive walking and biking score of 8.4 — Portland was actually assessed as fourth overall in this area — and dining, parks, and community was another strong spot for the Rose City at 6.9. However, childcare (1.0), health and safety (3.2), and housing affordability (4.1) were all found lacking using the data measured.

How do we actually transform “promising” 15-minute cities into real ones?

People may enjoy having nice restaurants and cafés to walk and bike to, but real livability must support people across different income levels and phases of life. Unless concentrated efforts are made to increase availability of affordable housing in high opportunity urban areas in tandem with making easier for families to live in or near urban centers and increasing protection and support for communities at-risk of displacement by gentrification, the U.S. risks 15-minute cities becoming just one more luxury most Americans cannot afford. These investments will be just as vital to the future of 15-minute cities as investments in creating safer infrastructure for people walking, biking, and rolling.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.