Seattle Parks and Recreation staff set off a bit of a backlash last week when they shared a blog post praising its four golf courses for serving as valuable habitat for urban wildlife. The department proclaimed the 528 acres occupied by the publicly owned golf courses are home to a long list of species including coyotes, beavers, raccoons, tree frogs, herons, river otters, wood peckers, and more. Trout and salmon bearing streams are located within or downstream of golf courses as well, wrote Seattle Parks’ staff.

“These wild animals may not be playing a round of golf, but they rely on the habitat in these parks to live in our city,” quipped writer Chris Nicholson in the blog post.

Some Seattleites didn’t buy it.

“Mown grass is a wildlife desert. Pesticides are bad for wildlife. The land could be used for affordable housing, community services, and the actually wild spaces that wildlife needs to thrive. Also, the water expended to maintain the grass is an insane waste of resources,” tweeted @hikemonster in a response that encapsulated much of the criticism directed toward the post on Twitter.

Golf courses have become a hot topic in growing Seattle where publicly owned land and affordable housing are both in short supply. Data from a 2017 study completed by EMC Research for the City of Seattle shows that golf courses are the least utilized facilities owned by Seattle Parks and that the number of people accessing them is on the decline. According to EMC’s data, only 12% of Seattle residents visited golf courses two or more times per year, and only 3% visited golf courses 10 or more times annually.

Thus, when Nicholson kicked off his blog post with the line, “When most people think of parks, they don’t initially think of golf courses,” he struck on a vein of truth — a substantial majority of Seattleites do not think of golf courses as parks because they simply do not visit or use them.

It is also important to note that those numbers do not take into consideration whether those visitors actually played golf during their visit since Seattle Parks occasionally opens golf courses for limited community access, such as for sledding on snow days. However, if rounds of golf played and green fees collected from golfers are any indication, the amount of golf played is decreasing in tandem with sinking visitor numbers. According to Mike Eliason’s 2019 article in The Urbanist, “Unlike Seattle, Golf is Really Dying,” rounds of golf played on the City’s municipal courses declined by 43% between 2000 and 2017 when adjusted for population growth. This is in keeping with national trends showing younger generations have been less drawn to the sport, which has a well-documented elitist, racist, and sexist history. (Gentleman Only, Ladies Forbidden)

Fewer green fees collected from golfers has resulted in a downward trajectory in revenue for Seattle’s golf courses. EMC found that from 2013-2017 golf courses were unable to meet their financial targets. Additionally, golf courses have not been able to raise the capital funding necessary to make investments in aging infrastructure, leaving a Golf Master Plan created by Seattle Parks in 2009 unfunded.

Do golf courses really contribute to biodiversity in Seattle?

In an effort to strengthen their case for preserving golf courses in an era of declining use, some golf course boosters are turning to biodiversity to bolster their argument.

Roughly 8% of land owned by Seattle Parks is occupied by golf courses, which is not an insubstantial amount of park acreage in the city. According to the Trust for Public Land’s 2021 ParkScore index, Seattle scored 55 out of 100 for total park acreage, identifying acreage as one of the city’s weak spots when analyzing park performance. For golf supporters, keeping these lands as golf courses instead of converting them to other uses such as housing is imperative because of the city’s need to maintain or increase green space.

However, unlike golf courses, most Seattle park land is much more accessible and widely utilized by the public. That’s where golf course supporters turn to wildlife as beneficiaries of golf course land, arguing that the green space occupied by golf courses functions as wildlife habitat or corridors. Yet, the amount of golf course land that can be actually used by wildlife is far less than its total of 528 acres.

Seattle Parks acknowledged in its own post that the bulk of the wildlife habitat within its golf courses is “contained in the edges and natural areas.” While the department did not cite exact acreage numbers, it did share that it is currently restoring 30 acres of golf course land with help from the Green Seattle Partnership, SPR’s urban forest restoration program. In total, Green Seattle Partnership has identified 85 acres within golf courses for restoration, representing only 16% of the total land area.

Pollution is also a major concern when it comes to golf courses. While Seattle Parks has made efforts to eliminate the use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers used on its meadows in partnership with a certification program administered by the Audubon Society, grass fairways still demand of the application of these hazardous substances which harm wildlife and enter the city’s watershed. Additionally, the regular mowing and removal of weeds on grass fairways makes the land inhospitable as habitat for birds and other pollinators.

With this context, the argument for biodiversity on Seattle’s golf courses falls short, even when you consider the charismatic coyotes that venture out on the fairways from time to time. Those coyotes would probably be happier loping around the dense trails of Seward Park or another similarly verdant spot anyways.

Using golf course land for public benefit

A burgeoning movement calling for publicly owned golf course land to be put to greater use in cities is emerging nationwide as more cities put former golf course land to use as housing and park space. A 2018 report from the National Golf Foundation found that more than 200 golf courses closed in the U.S. in 2017 alone as golf facilities continue to exceed demand from golfers.

Some of Seattle’s neighboring cities and suburbs have already embraced the trend of converting golf courses to new uses. In Kent, a 492-unit urban and garden style apartment development with 12,000 square feet of retail is in development near its town center on land formerly occupied by a nine-hole golf course, while in Mountlake Terrace a nine-hole golf course was converted into a 55 acre passive park, expanding the footprint of Lake Ballinger Park and increasing the amount of land dedicated to wildlife habitat.

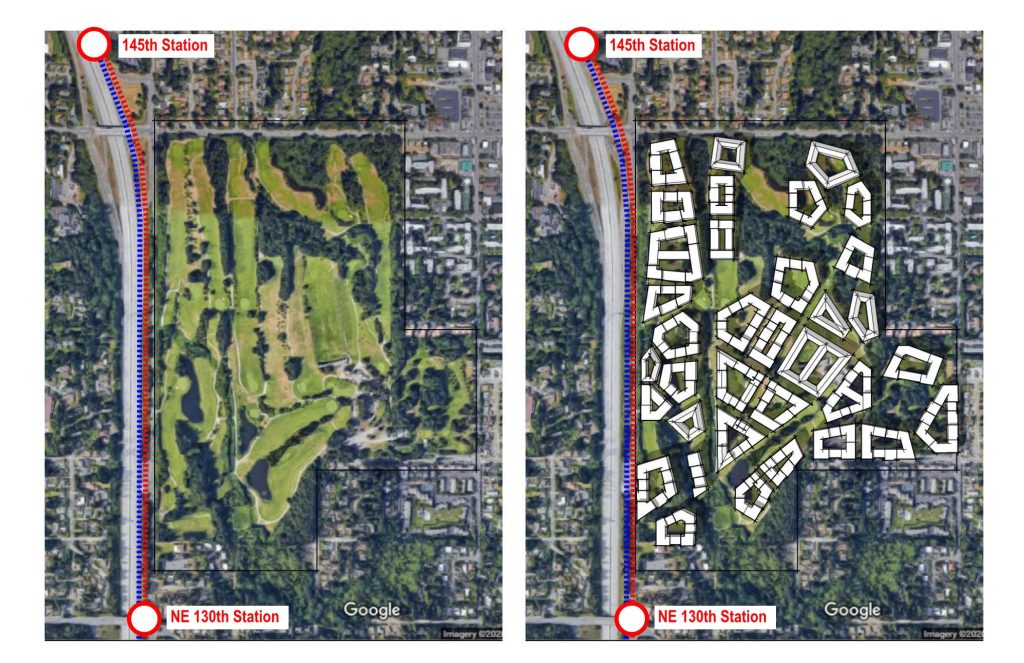

Beyond actions taken by other cities, however, recent developments have put new urgency on examining the future of publicly owned golf courses in Seattle. On August 6th, 2021, the Sound Transit Board voted to approve plans to keep the expansion of Link light rail mostly on schedule and actually accelerating 130th Street Station. This means that two light rail stations will be opening within walking distance of Jackson Park golf course: NE 145th Street Station in 2024 and 130th Street Station in 2025. The City has been engaging in planning efforts around these station areas, including a community survey soliciting feedback on proposals to change the surrounding zoning from single-family to commercial/mixed use and multi-family residential zoning that closed in late July of this year.

The millions of dollars in public funding that have gone into the development of these light rail stations has spurred housing advocates to call for a reevaluation of the 160 acre, 27-hole Jackson Park golf course in particular. In an op-ed for the The Urbanist, titled “Let’s Tee Off for Housing,” Ryan DiRaimo makes the case for converting the course into a new eco-district that could house 35,000 people on the 60 acres of fairways and preserve the remaining 100 forested acres as public open space, all of which would be within a short walk of rapid transit.

DiRaimo also supports removing the name of genocidal U.S. president Andrew Jackson from the park, suggesting renaming it after Jim Ellis, a Seattle planner who dedicated his professional life to the expansion of the mass transit in the region and set the groundwork for today’s Link light rail system.

Ensuring that affordable housing makes its way into the mix would be an important way for the City to further distance itself from a legacy of exclusion, and enable a diverse array of humans — and wildlife — to benefit from this publicly owned land.

Regardless of the particular solution, the status quo of an unpopular, money-sucking public golf course next to a soon-to-open light rail station is untenable. The first planning concern within a short walk of a transit station should be increasing the count of human residents rather than raccoons and coyotes.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.