Bellevue’s reputation as our region’s most car-dominated metropolis is well-established and, to my chagrin, well-founded. Guided in part by the desires of our city’s wealthy landowners, our elected officials have historically made policy choices that make using a personal car the easiest and fastest way to get around Bellevue. However, as the city moves from its suburban past of Kemper Freeman to its urban future of Amazon and Facebook, even conservative leaders have recognized the importance of shifting to a more multimodal transportation network.

The city, ever one for lengthy process and data-gathering before making common-sense safety and mobility decisions, has tasked the Transportation Commission with the development of the Mobility Implementation Plan — a complex but important year-long policy discussion that has the potential to (at least partially and slowly) rid Bellevue of its car dominance.

Take the Mobility Implementation Survey to help Bellevue build a better transportation future!

All of the body’s discussions revolve around the principle of concurrency. Because of the Growth Management Act (every policy wonk’s favorite piece of state legislation), cities like Bellevue are required to ensure their transportation systems have enough capacity to accommodate planned growth. When a city’s transportation system has enough capacity to accommodate expected demand, it’s said to be meeting concurrency.

However, what if a new development in a rapidly-growing neighborhood would lead to more trips than what the current system can accommodate? In that case, the developer would be required to fund the transportation improvements necessary to bring the system back into concurrency — an arrangement that saves the city money while still allowing Bellevue to accommodate new growth. Although a great system in theory, Bellevue’s current concurrency policies leave much to be desired. Most importantly, the current approach to concurrency and the required performance targets to meet it are exclusively related to automobile traffic.

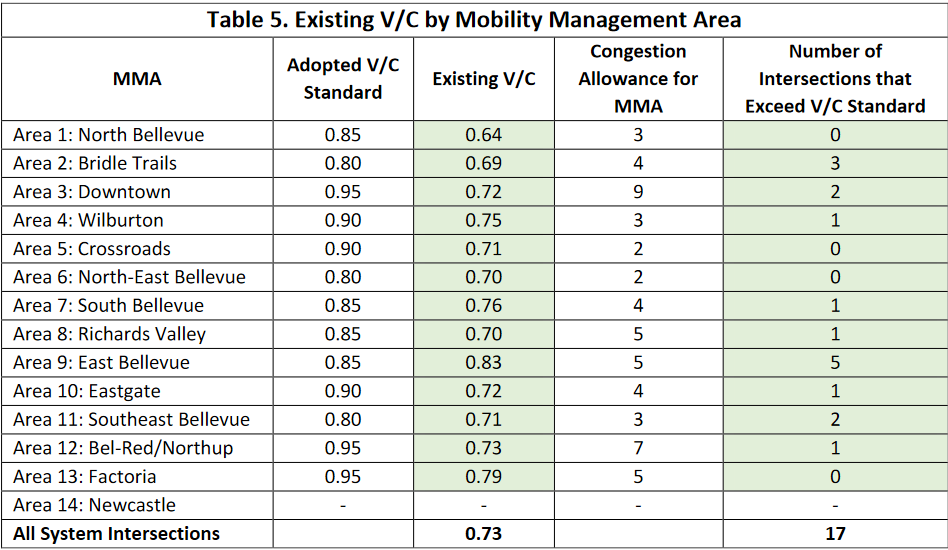

A neighborhood is meeting concurrency when the projected volume of automobile traffic divided by the total capacity of roadways (abbreviated as v/c) is less than its particular target. This means that, even though significant portions of our residents walk, bike, and take transit to get where they need to go, their needs are not inherently accounted in the way that the needs of drivers are. Worse still, because concurrency currently only examines automobile capacity, developers are required to fund projects that increase vehicle throughput when their projects would lead to the city failing concurrency. Because of induced demand, this just locks in further emissions and traffic at a time when the city needs to be reducing both.

Luckily, it’s the goal of the Mobility Implementation Plan (MIP) to change this paradigm by establishing new standards for all modes (walking, biking, transit, and driving) and, importantly, allow impact fees go towards the construction of multimodal facilities. Which facilities will be prioritized in the use of these fees will largely depend upon the standards that the transportation commission chooses to set for each mode and just how deficient the current infrastructure is compared to those standards.

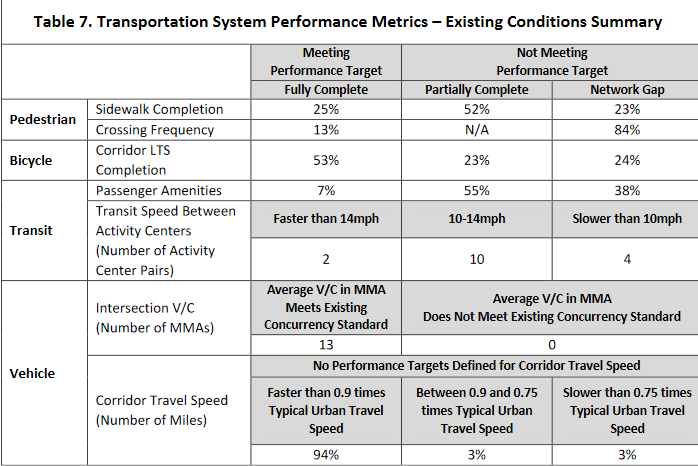

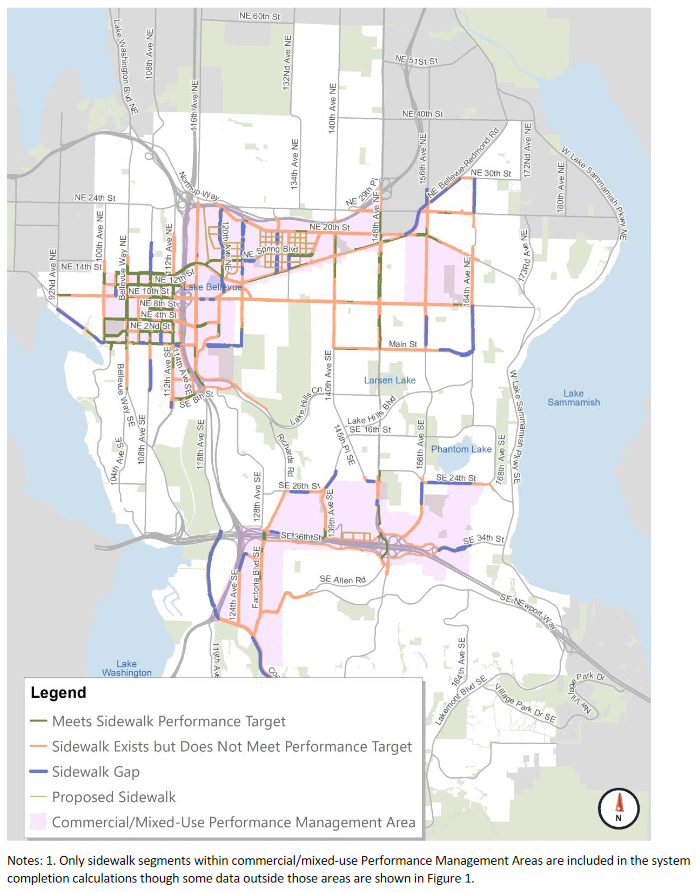

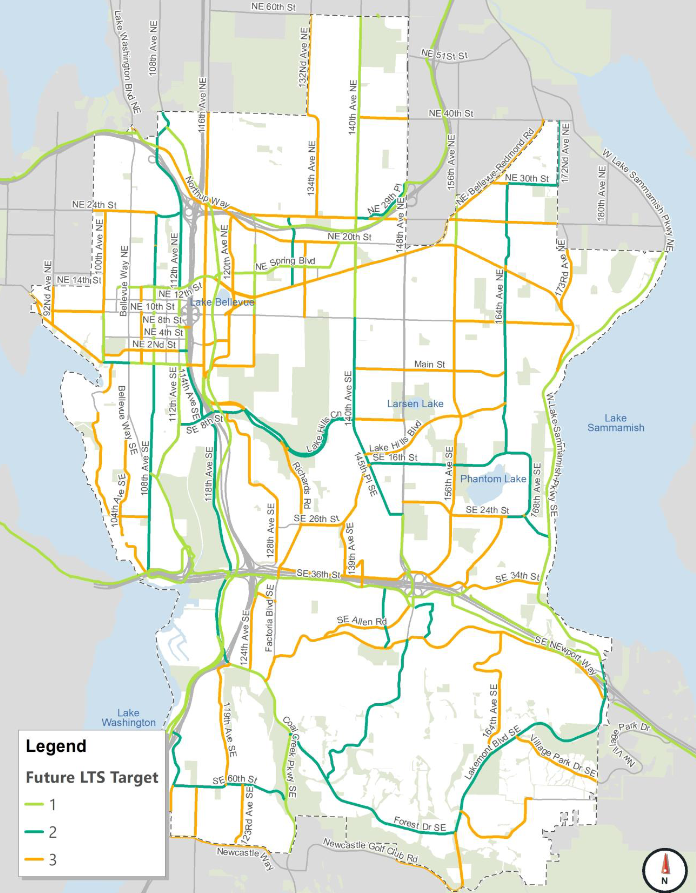

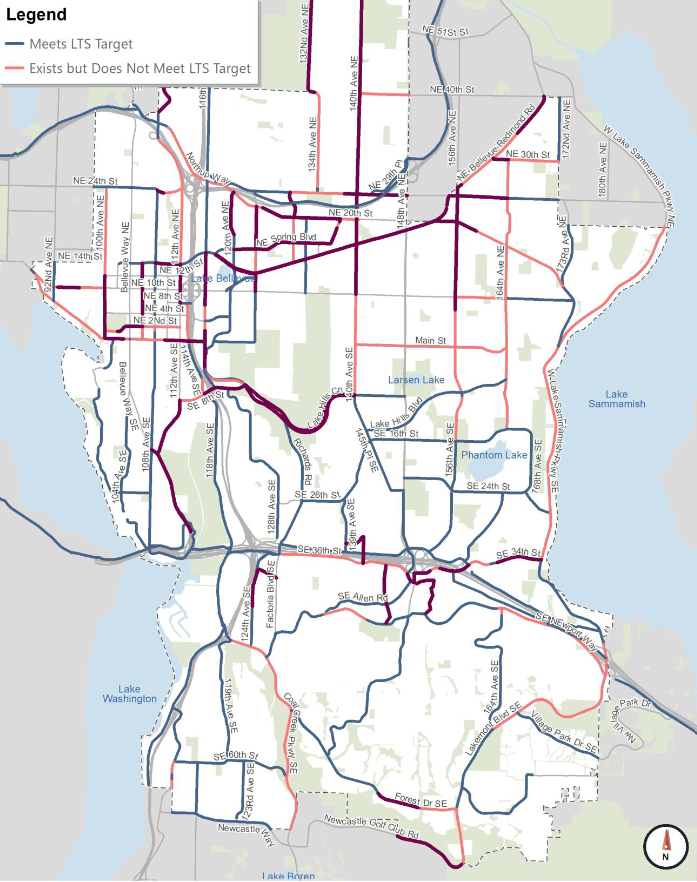

For example, transportation staff outlined the level of completion of each modal network based upon standards set in the city’s 2017 MMLOS Report. Although these standards are not necessarily the ones that the Transportation Commission will ultimately choose for the MIP, they paint a sobering picture of Bellevue’s multimodal infrastructure.

- In the city’s designated growth areas, only 25% of Bellevue’s pedestrian network is meeting performance targets of at least 12 to 16 feet of combined landscape strip and sidewalk space.

- Only 53% of Bellevue’s cycle infrastructure currently meets the expected Level of Traffic Stress (LTS) metric.

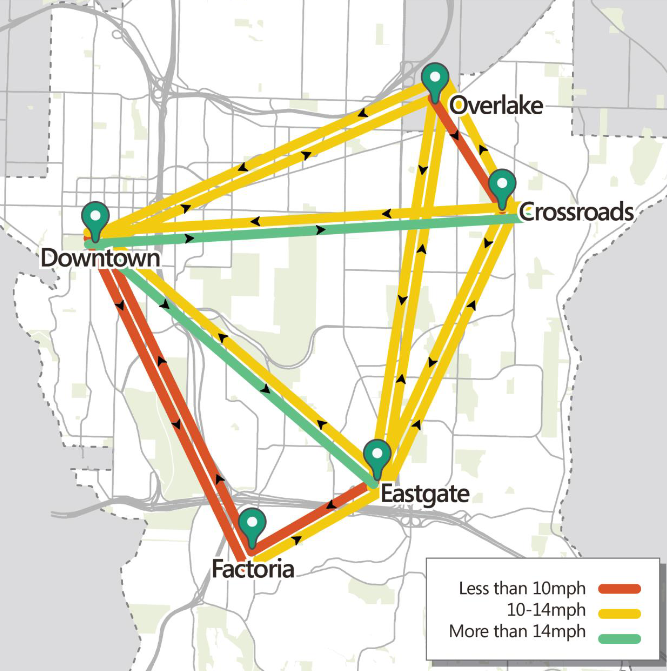

- 14 of 16 neighborhood transit connections (e.g., Downtown to Factoria and Crossroads to Eastgate) run at speeds of less than 15 mph.

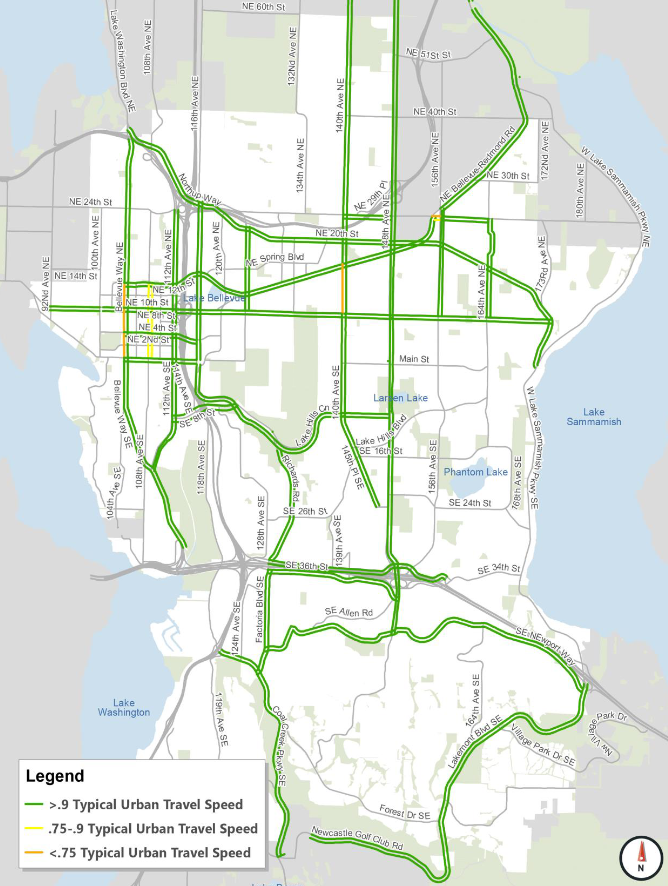

- In contrast, 94% of Bellevue’s priority roadways are operating near the expected Urban Travel Speed.

These statistics and standards paint a clear picture: because of historical policy choices, Bellevue’s road network is currently adequate to accommodate demand, but our pedestrian, cycling, and transit networks are in need of prioritized investment.

As mentioned previously, however, these statistics (and thus which infrastructure will be prioritized) are significantly influenced by the targets that the Transportation Commission sets for each mode. If the body selects low or easy-to-meet targets for multimodal facilities while increasing targets for road infrastructure, it’s possible that Bellevue’s history of automobile-dominance will continue into the future.

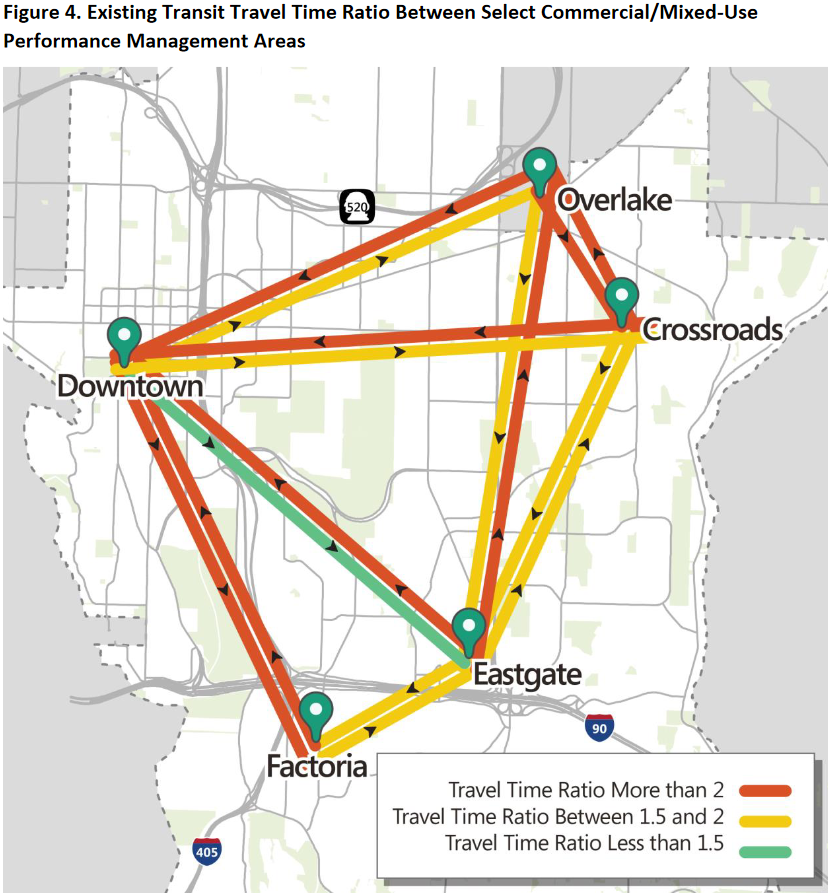

Recent commission discussions hint that this may the direction the body is going — in their July 8th meeting, commissioners directed staff to present transit performance data in a way not dependent on route speed, but rather based on a ratio of transit to automobile travel times. Staff’s report claims that conditions of transit travel times being less than 1.5 times greater than corresponding car travel times would encourage choice riders to choose transit. However, in a growing and urbanizing city, there are situations when transit travel can (and should) be faster than car travel. Tying transit standards to car travel times means that, if car travel times increase, the acceptable travel times for transit increase along with them, thus lowering the quality of the transit experience. This would be a disservice to existing transit riders and not serve to encourage drivers to make the switch. And even by this standard, Bellevue transit facilities are still shown to be significantly lacking.

Luckily, there is a way for you to make your voice heard and help the Transportation Commission avoid further blunders. Bellevue is hosting an important survey on the city’s public engagement portal that allows you to share your experiences walking, biking, taking transit, and driving in the city. The results from this survey will inform staff and commissioners which facilities the community wants to be prioritized in the MIP, so it’s important that community members speak strongly for increased prioritization of walking, rolling, biking, and transit investments. You can provide feedback no matter where you hail from, but if you live, work, or study in Bellevue, your feedback is especially important.

Take the Mobility Implementation Survey to help Bellevue build a better transportation future!

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.