Participating mayors pledge to enlist an additional 1,000 cities to achieve net zero carbon emissions.

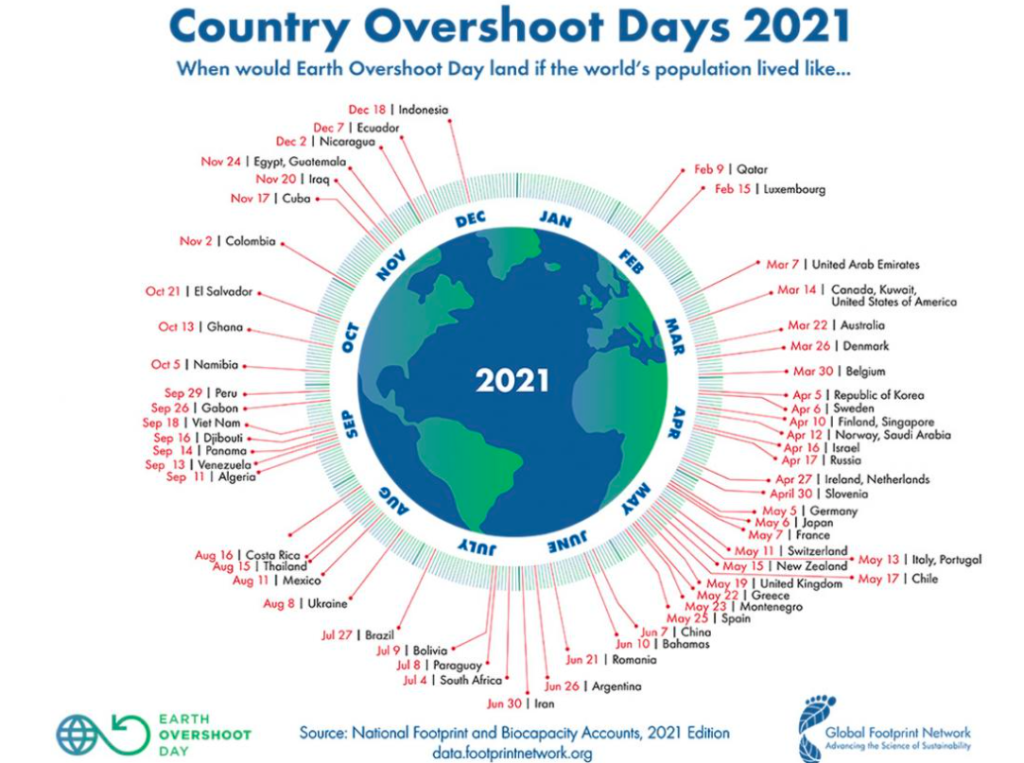

July 29th, 2021 marked an important date that only the most evil supervillains would celebrate, yet no one should forget. Dubbed Earth Overshoot Day, the date represents when the global population used up 74% more biological resources than our planet’s ecosystems can regenerate in a given year — in other words, the moment in 2021 when our combined resource consumption hit a level that would require the biological capacity of 1.7 Earths to sustain, according to calculations from the Global Footprint Network.

To put into context what resource bingeing countries like the United States owe to more frugal developing countries, such as Bhutan for instance, the U.S. actually passed its own 2021 Earth Overshoot Day months earlier, back in mid-March alongside fellow energy guzzlers Canada and Kuwait.

In 2020, restrictions resulting from the Covid pandemic pushed the date back to August 22nd; yet, despite global transportation emissions remaining below pre-pandemic levels, factors like a rise in global energy use and increased deforestation of the Amazon rainforest nudged up consumption by 6.6% overall, with carbon alone constituting 57% of humanity’s ecological footprint.

Like the record wildfires and floods making news across the world, Earth Overshoot Day provides another stark reminder of the gravity of the climate crisis confronting us. As the climate crisis becomes increasingly difficult to dismiss, more elected officials are stepping up to pledge action to decrease carbon emissions. Among the most vocal of these are mayors, an indicator of the important role cities have historically held as laboratories of social, economic, and environmental change.

The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) will take place in Glasgow in late autumn of this year. As part of the lead up to the event, twelve mayors from around the globe have endorsed a call to action letter promoting the Race to Zero campaign for cities alongside trade unionists. According to a press release, the mayors have committed to recruiting 1,000 cities across the world to join their coalition, which promises to “deliver inclusive climate action plans, consistent with constraining global temperature rise to 1.5°C set out in the Paris Agreement, and initiate a green and just recovery from COVID-19.” Signatories to the call action include:

Eric Garcetti, Mayor of Los Angeles and C40 Chair Jenny Durkan, Mayor of Seattle Steve Adler, Mayor of Austin Ada Colau, Mayor of Barcelona Susan Aitken, Leader of Glasgow City Council Sylvester Turner, Mayor of Houston Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London Giuseppe Sala, Mayor of Milan Kate Gallego, Mayor of Phoenix Ricardo Nunes, Mayor of São Paulo Randall Williams, Mayor of Tshwane Mohammed Adjei Sowah, Mayor of Accra Sharan Burrow, General Secretary, International Trade Union Confederation

Key elements of the call to action include a pledge to create new jobs and opportunities for training, further social equity by to provide social protection and affordable access to essential public services, engage in new partnerships on the local and national level, and secure the investment necessary for a “just and green recovery.”

All participating cities are members of the C40 Knowledge Hub, an international network of nearly 100 city governments committed to confronting the climate crisis with a “a science-based and people-focused approach.”

Big promises have been made, but can mayors deliver real results?

Over the past 26 years, the United Nations Climate Conference has moved from a fringe event to one that garners international attention. Yet, apart from the short-term dip in carbon emissions spurred on by pandemic lockdowns, CO2 levels have continued to climb even as we bear witness to the ecological and social damage inflicted by a changing climate.

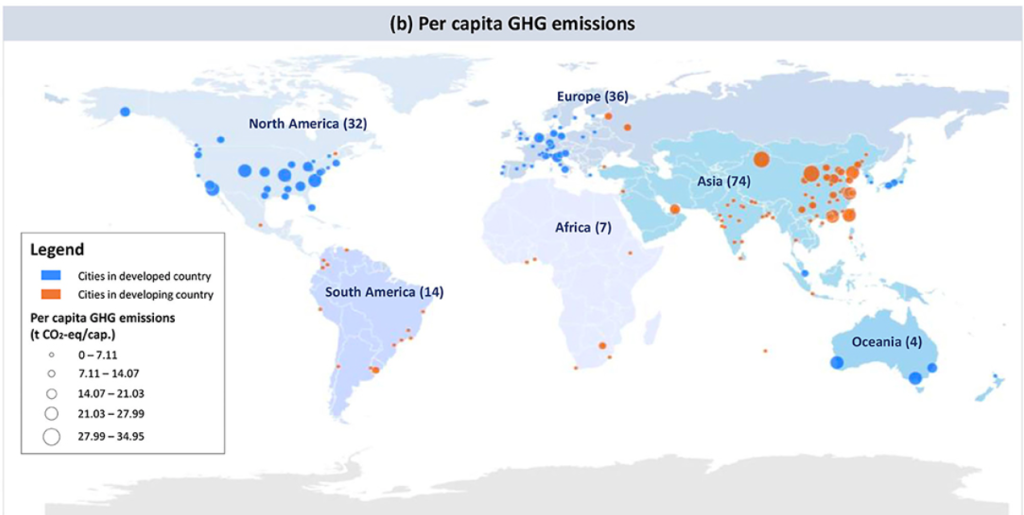

A study published this July in Frontiers in Sustainable Cities tracked the effectiveness of greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction policies implemented by 167 cities across the globe. The study found that the top 25 cities accounted for 52% of urban carbon emissions. While nearly all of these cities were located in China, cities in Europe, Australia, and the U.S. had significantly higher per capita emissions than cities in developing areas including China. Additionally, industrial buildings and processes were primary areas of carbon emissions in China, while road transportation and residential and commercial buildings accounted for the bulk of emissions in North America and Europe.

Of the 167 cities in the study, 113 cities had already set traceable targets for GHG emission reduction. In China, the national carbon emission reduction target of 18% has resulted in many cities establishing their own goals, and cities with higher urbanization rates and more developed economies like Guangzhou and Shenzhen have set more ambitious targets of 23%. Overall, as of 2019, China announced it surpassed its own national targeted carbon intensity reduction goal of 40% to 45% by achieving a 48% reduction compared with 2005.

In the European Union, 90% of cities have set the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 to synch up with the EU’s general carbon reduction target. The push to shift the timeline to 2040 or sooner will force these cities to establish more ambitious policies, although a small number of European cities have already advanced to a 2040 or 2030 timeline for carbon neutrality.

In North America, Canada has similarly set 2050 as its target date for carbon neutrality; however, in the U.S. the situation is more complicated. Under the Trump administration, the U.S. declined to establish carbon emission targets. President Joe Biden broke from that policy when he declared that the U.S would achieve a 50% to 52% reduction from 2005 levels in GHG pollution by 2030. The newly established target is an improvement, but it breaks from other developed countries pledges to achieve carbon neutrality, making it all the more imperative that American cities continue to push for greater action.

According to data compiled in the report, there was a clear emission decrease in 30 cities during the time period studied (2012 to 2016). The top four cities with the largest per capita emission reductions were Oslo, Houston, Seattle, and Bogotá, while the report cited the top four cities with the largest per capita emissions increases as Rio de Janeiro, Curitiba, Johannesburg, and Venice. It should be noted that another study completed in 2018 found that carbon emissions were decreasing in Venice, a sign of how difficult it can be to measure carbon emissions and how often outputs can be subject to change and debate.

Should Seattle declare itself a climate leader?

Seattle should be proud of its achievement in decreasing per capita carbon emissions; however, ongoing population growth actually has resulted in a net increase in carbon emissions in the city and surrounding region, underscoring the need to push for greater progress.

On a brighter note, Seattle succeeded in approving its own Green New Deal back in 2019, and since then Mayor Durkan signed into law an executive order directing all city departments to collaborate together and with the Green New Deal Oversight board and Mayor’s Youth Climate Council to further the objectives set out in Seattle’s Green New Deal. Despite the executive order and international pledges, Mayor Durkan has sometimes stood in the way of climate work as she has delayed, canceled, and cut funding to various bike, pedestrian, or transit projects and “pivoted” from a pledge to advance congestion pricing in her first term.

In 2020, the Seattle City Council directed 9% of long-term JumpStart Seattle corporate payroll tax revenue to fund Green New Deal work; current estimates place the amount at about $20 million annually, which is expected to be spent on converting buildings from fossil fuel to electric heat, weatherizing residential buildings, and making them more energy efficient. The funding will prioritize homeowners earning 80% or less of Seattle’s median income and outreach for these programs will be conducted with residents who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). Mayor Durkan opposed the payroll tax, fearing it would scare off job growth and upset major corporations. Facing a veto-proof Council majority, she let it become law without her signature and later redirected proceeds to fill holes in her annual budget.

However, to meet the ambitious carbon neutrality target of 2030, Seattle will need to engage in even bolder action. Policies espoused by writers for The Urbanist such as investing in safe infrastructure for walking, biking, and rolling, increasing options for electric-powered public transportation, and amending zoning codes to allow for the construction of more multifamily housing and the development of more urban villages throughout the city all would help push the dial in the direction of carbon neutrality for Seattle.

On their own, these actions will not be enough to prevent the planet from warming to a degree that scientists forecast will endanger life as we know it on our planet, but if Seattle and other cities can both follow through on their pledges with real results and inspire 1,000 — or more — cities to do the same, we will make real progress in preventing the climate crisis’s worst possible outcomes.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.