The progressive wing of Seattle politics is having a vigorous debate about the future of the city with plenty of new policy ideas bouncing around. So, what’s going on in the center and right-wing politics? It’s hard to find anything new, but certainly the age-old issue of crime (and specifically getting tough on it) is rearing its head this primary season.

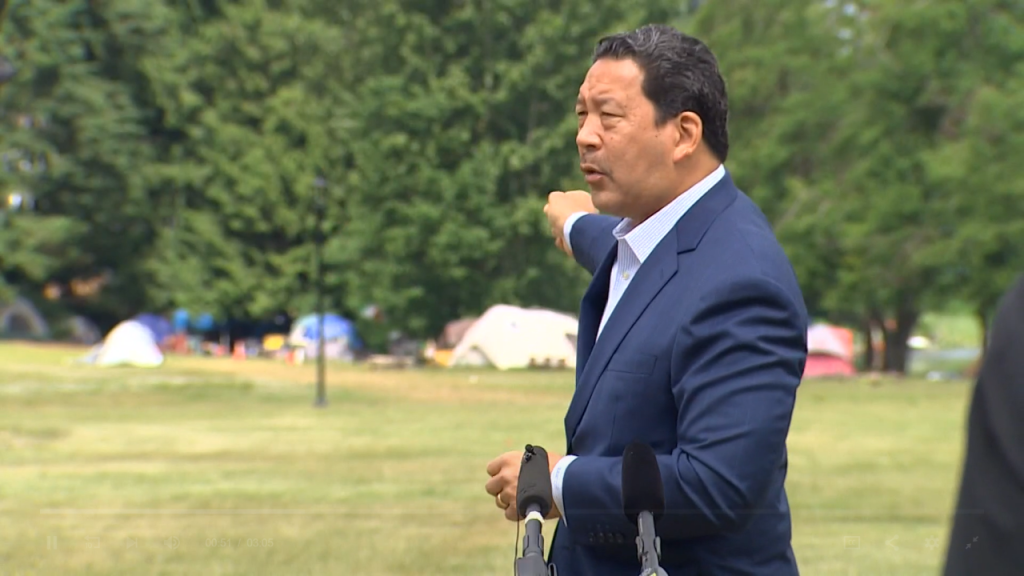

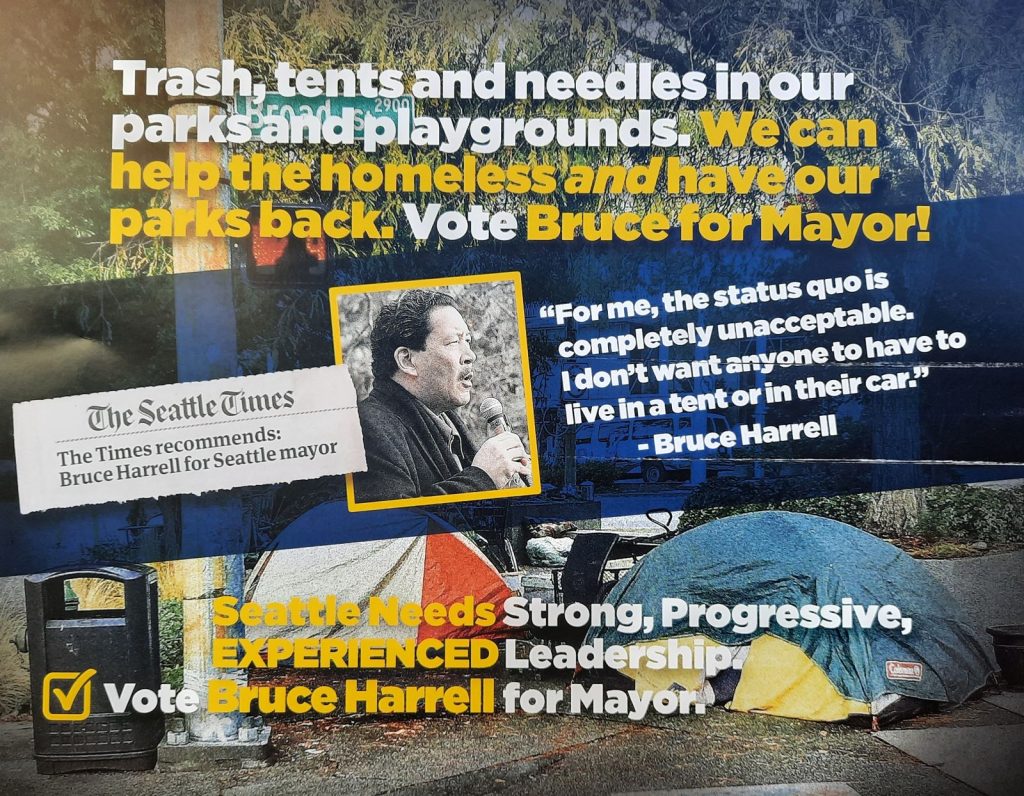

Interim Seattle Police Department (SPD) Chief Adrian Diaz went on KIRO Radio this week to essentially stump for Bruce Harrell’s campaign, arguing the next mayor must increase police funding, hire more officers, and toughen sentencing. “We need a mayor that will support the police department,” Diaz said.

The police chief’s comments amounted to electioneering and flaunted laws banning election activities in an official City capacity. However, he may not face any consequences for this, much like most of the SPD officers who attended the January 6th insurrection or the handful that illegally voted from their work address rather than home addresses in the suburbs. Frankly, it’s a pattern for SPD to believe it’s above the law and above reproach.

Centrist talking heads also seem to be drawing blanks when it comes to core change they’d make beyond more police and getting tough on homeless people and protesters. Take for example, a recent column by Joni Balter in Crosscut. She spends a lot of words criticizing progressive candidates, but what are the core problems she highlights and the solutions? Well, activists showing up at elected leaders’ homes to protest — particularly the centrist ones — seems to be the main thing that’s gone wrong in her eyes. What does she propose to do about it? Mainly blame progressive leaders and demand more police funding and tough-sounding rhetoric.

By the way, I should probably clarify: protesting outside an elected official house is not illegal. However, it does feel mean-spirited to some. And if it’s accompanied by threats and/or hate speech, there may well be legal recourse.

Like the Police Chief, Balter points to an uptick in the homicide rate to support her assertion that cutting police funding is ludicrous and throwing more money at them is the only serious solution. But with SPD’s budget still on a massive upward trend long-term even after the Seattle City Council trimmed 18% off SPD’s books last year, it’s not clear what more money would accomplish. Even with the homicide spike during the pandemic, Seattle has significantly fewer homicides and violent crimes per capita now than in the 1980s and 1990s. Seattle spends more on policing despite fewer violent crimes, but at the same time the clearance rate (percentage of crimes that are solved) has actually gotten worse. Plus, despite a decade of reform efforts, crowd control tactics have grown more brutal and counterproductive.

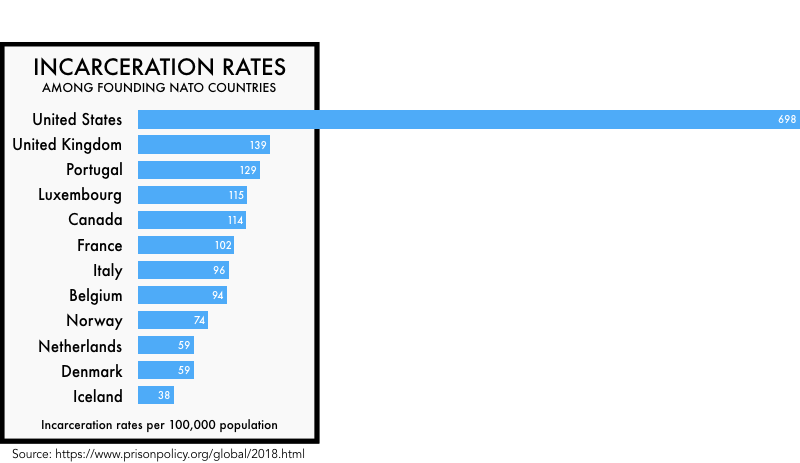

What is one to make of these statistics? Reflexively increase police funding to say we did something? That’s what we’ve done throughout the drug war era and see where it’s gotten us. The United States has the highest incarceration rate and the largest prison population in the world, accounting for a quarter of all inmates with less than 5% of the world’s population. And yet centrists and conservatives are never satisfied. It’s always the right time to get tough on crime when there’s an election to win. We as voters have to stop rewarding these cynical fear-based appeals.

Balter said she supports police reform, but it’s not clear which reforms and how she would hope to achieve them and how successful they would be — particularly without using the budget as leverage to bring the Seattle Police Officers Guild to the bargaining table and hold them to accountability measures. She frets that defunding the police could hurt Democrats higher up on the ticket in coming elections, but this is a rather generalized and amorphous anxiety on which to base city policy. Harrell has been critical of defunding the police, and that does seem to be the primary issue he’s tangibly parted ways with the city council since he left.

It’s pretty clear Balter favors Harrell in this race, but even she admits he has a tightrope to walk. Harrell is only 18 months removed from a 12-year stint on Seattle City Council and yet he’s running as an outsider and painting himself as an entity separate from City Council’s problems, which apparently all quickly developed after he left.

“Based on my conversations at farmers markets and grocery stores, the city has lost total confidence in the city council,” Harrell told Balter in an interview last week. “They have lost confidence in the executive office working with the council. I make it crystal clear that I am tired of criticizing the past. I am going forward.”

The refusal to grapple more deeply with why voters apparently have grown impatient with the city council and the executive branch happens to be convenient. Harrell had three terms to try to make a dent in homelessness, public safety, reforming the police, addressing the housing crisis, curbing climate emissions, and shrinking the racial wealth gap. He endorsed the last two elected mayors in Ed Murray and Jenny Durkan. Even with an ally in the Mayor’s office, he mostly didn’t make a dent. Still, he promises swift decisive action and a data-centered approach.

During a June campaign event, Harrell stood in front of a homelessness encampment near Broadview Thomson Elementary School in Bitter Lake and promised the camp wouldn’t exist if he were elected. The how part gets murky. Would he sweep the encampment? He didn’t say that. However, Harrell does support camp removals in certain cases, but doesn’t use the word “sweep.” So rather than a new policy, he seems to be promising a rebranding of existing Durkan administration policy on encampments. What an innovator!

Harrell backs Compassion Seattle’s charter amendment, an unfunded mandate to spend an extra roughly $18 million per year and create 2,000 “emergency housing” units within a year. The Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce is throwing its weight behind the measure while at the same time pursuing a legal challenge of the Jumpstart payroll tax that would be a key source of funding for its programs should it pass. For all the Council’s purported problems, they did deliver the goods when it comes to new progressive revenue, and that’s why Compassion Seattle had the gall to not propose a major initiative without dedicated funding, pointing instead to the freshly passed payroll tax.

The charter amendment is the brainchild of Tim Burgess, a long-time colleague of Harrell’s on the City Council, who retired two years before him after a 71-day stint as interim Mayor. Why Burgess and Harrell couldn’t get a similar package of policies passed when they were in office is unclear. Burgess nearly succeeded in criminalizing panhandling and has been a major critic of corporate taxation, while Harrell has been lukewarm on it. Regardless, the charter amendment is likely to be a major issue in the November election, and early polling suggests it will pass — unless a lot changes by then. Balter’s stance on the charter amendment, by the way, is that it’s promising but she did ponder if maybe it’s not pro-sweeps enough, channeling former hardline City Attorney Mark Sidran.

The former Council President has also promised to foster better relations between Mayor and Council. Nonetheless, the charter amendment is designed to rewrite the City Charter to circumvent the normal legislative process. The Urbanist Elections Committee opposes Compassion Seattle because it seems designed to justify sweeps and force the city to build temporary housing to make the unfunded quotas rather than the permanent supportive housing needed to break the cycle of homelessness and truly bring this emergency to an end. Writing policy and budget levels into the charter is a blunt instrument not in line with good governance. Compassion Seattle signature gatherers have promised their amendment will end the homelessness crisis, but in itself it’s insufficient. And that sets up a dangerous problem for voter expectations that could further poison the well for real solutions.

A couple thousand emergency shelter units when more than 10,000 people are homeless in the county are not going to cut it. Plus, homelessness isn’t a static problem and people cycle in and out of shelters and housing. When rents spike, so too does homelessness. That means the problem can get worse even as we invest more in it unless we also address the housing affordability crisis. Harrell’s platform on zoning reform is the weakest of leading candidates which would be an obstacle to addressing those interlinked problems. Thinking a quick but short-lived and minor infusion of dollars will turn the tides is naïve. The homelessness emergency persists because it’s a gnarly multifaceted issue, especially in an environment of self-imposed budget scarcity.

Homelessness, housing affordability, and stalled out police reforms are problems that can be solved. But not by incremental tinkering and rebranding exercises. We need leaders with courage to tackle these issues head-on.

August 3rd is the last day to vote in the Primary. The Urbanist’s endorsements are here.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.