Update: Since this article was initially published, Councilmember Kshama Sawant has formally submitted a resolution calling on the City to “support community demands to fund quality affordable social housing to prevent and reverse displacement” and “urge the Office of Housing to fund the affordable housing project proposed by New Hope Community Development Institute.”

Last summer when Councilmember Kshama Sawant stood on the steps of New Hope Missionary Baptist Church in Seattle’s Central District, she called on the City to fund 1,000 new affordable housing units over three years for “historic residents and those displaced” from the neighborhood, which for decades was home to the largest Black community in the Pacific Northwest.

At that time Councilmember Sawant and advocates from the community stopped short of explicitly calling for reparations for Black Seattleites, who statistically have largely been left out of the economic growth accompanying the city’s most recent period of population expansion. Now a year later, the demands have shifted. On a sunny Saturday afternoon, Sawant and an expansive coalition of nonprofit organizations, faith-based institutions, and affordable housing providers held a rally for “reparations, unity, and affordable housing” held near the same site. The rally included live music and impassioned speakers.

“We are asking you, we are pleading for you to give reparations back, to give back what’s been stolen and taken,” said Pastor Lawrence Willis of True Vine of Holiness Missionary Baptist Church at a press conference Wednesday promoting the rally and cause.

Reparations, which are defined in the dictionary as “the making of amends for a wrong one has done, by paying money to or otherwise helping those who have been wronged,” have been a sensitive topic in the U.S. ever since the American government failed to pay reparations to freed slaves after the end of the Civil War. The idea to redistribute some 400,000 acres of Confederate land among the 3.9 million newly liberated slaves was developed by a group of twenty Black leaders in Savannah, Georgia, eleven of whom had been born free in slave states and thus would not have benefited from the action — though they faced racism and prejudice throughout their lives. Their petitioning resulted in Special Order #15, which was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln. Sadly, the act was overturned after Lincoln’s death by Andrew Johnson, setting into motion a pattern of ignoring or breaking promises made to Black Americans and advancing discriminatory policies favoring wealthy, mostly White landowners, some of which like exclusionary zoning and the mortgage interest tax deduction persist to this day.

After decades of stagnation in the Federal government, could cities lead the way for reparations for Black Americans?

As gentrification continues to tighten its grip on Seattle, it is unsurprising that Black residents and allies are stepping up calls for reparations for harms that have been done, but the evolution in rhetoric can also be linked to changes in national discourse around reparations. This spring the U.S. House of Representatives voted out of committee for the first time ever HB 40, a bill requiring the Federal government to study how it could undertake reparations for descendants of enslaved Americans.

At around the same time, Evanston, Illinois attracted national headlines when it passed its Local Reparations Restorative Housing Program granting qualifying households up to $25,000 for housing down payments or home repairs. According to the City of Evanston, in order to be eligible for the program, individuals must have lived in Evanston between 1919 and 1969 or be a direct descendant of someone harmed by discriminatory housing policies or practices during this time period. People who have lived in Evanston after 1969 and can demonstrate discriminatory housing practices by the City may also be eligible.

Seattle also has a history of discriminatory housing policies harming residents who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). The recently rally for “reparations, unity, and affordable housing” was spurred by an op-ed published in the Seattle Times by Reverend Robert Jeffrey Sr. of New Hope Missionary Baptist Church.

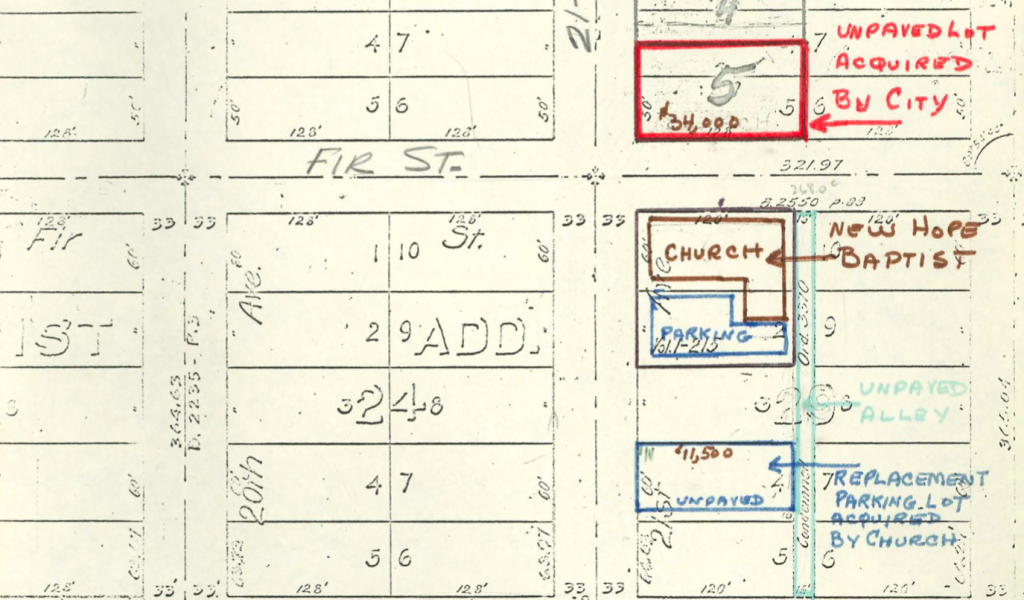

The op-ed makes the accusation that in 1969 the City of Seattle “forcibly took ownership” of two church properties “under the threat eminent domain and condemnation” to create Spruce Mini Park. Other Black property owners sold their land to create the park as well. Rev. Jeffrey is now calling for the City to return the land to the church or pay reparations for what was taken. In addition, he is demanding that City commit to $10.7 million of funding for the New Hope Family Housing Project, an 87 unit affordable housing development planned on land held by the church that is intended to provide housing to former residents of the Central District who has been displaced. Should the city opt not to return the land itself to the church, Jeffrey is currently pursuing an appraisal of the park’s land value for compensation.

“Why shouldn’t we quantify the pain?” Rev. Jeffrey asked. “We are tired of people estimating our pain and then throwing chump change at us.”

Councilmember Sawant has promised to put legislation in front of the City Council naming both of New Hope Missionary Baptist Church’s demands for reparations and additionally committing the City to paying compensation to “others who suffered under the racist urban renewal programs of the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s.”

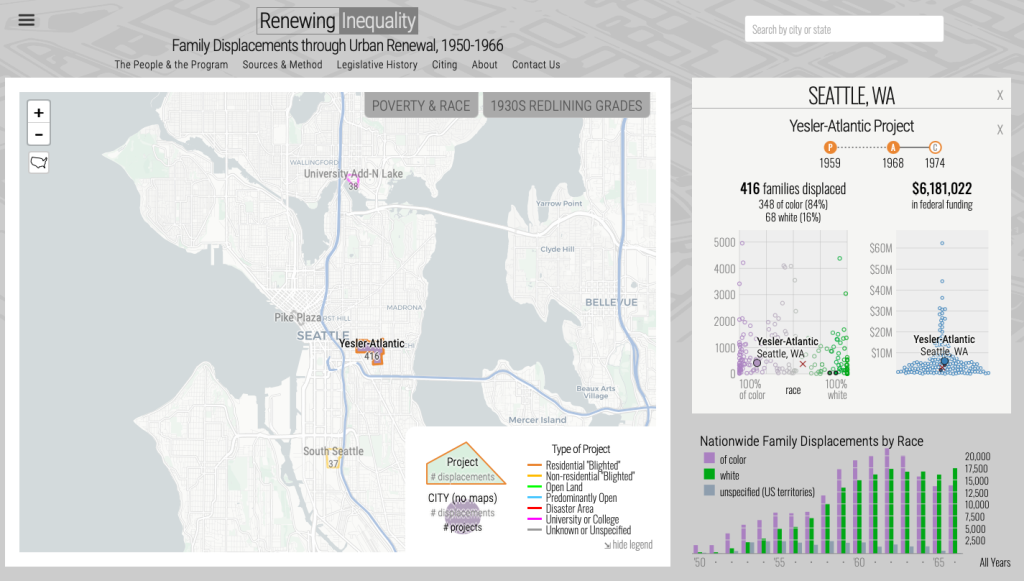

Like many American cities, Seattle engaged in urban renewal efforts with the financial backing of the Federal government between 1950 and 1966. According to research completed by the University of Richmond’s Renewing Inequality website, approximately $12.4 million was spent by the Federal government on three urban renewal projects in Seattle. These projects resulted in the displacement of 491 families, 73% of whom were people of color. The Yesler-Atlantic urban renewal project was by far the largest, spanning 340 acres in the present day Judkins Park, Mount Baker, and Central District neighborhoods. 416 families were displaced from the Yesler-Atlantic area alone, 84% of whom were people of color. Because of the disproportionate burden it placed on Black Americans, critics of the era referred to the practice of urban renewal as “negro removal,” a moniker that endures today.

Hammering out the details for reparations is not an easy task, yet the moral argument remains strong

Evanston became a pioneer when it created its reparations policy; yet, the city has faced criticism from some residents, with the lone vote against the initiative coming a Black city councilmember who felt that eligible recipients should receive the $25,000 as a cash grant to be used as they see fit instead of for costs related to home ownership. Such thorny debates around eligibility and compensation have always accompanied reparations efforts, but they have not lessened the moral case for making reparations when harm has been done.

Rev. Jeffrey has called for the City to begin by the returning the church’s land. However, it seems unlikely that such an action could be completed in isolation, and even if it were to be, it would incite questions of fairness over why an individual institution should receive reparations while many more BIPOC residents of Seattle have faced discrimination from the City.

It is also important to point out there are some potential weaknesses in their specific claim for reparations. According to Rev. Jeffrey, the case for reparations for the church stems from the fact that by selling the land to the City, the church lost out on the opportunity to acquire wealth as land values rose in the Central District in the decades that followed the sale.

However, records from Seattle’s Municipal Archives show that when the church was compensated $34,000 for the land used to create Spruce Mini Park, it also acquired land on the same block for $11,500 to create the parking lot it desired. In recent years, the church developed townhouses on some of that land which were sold for market value. Additional land held by the church on two parcels on opposite sides the same street (21st Street) are slated for the development of affordable housing according to Seattle in Progress, a website that tracks development activity.

To provide a bit more context, the acquisition of Spruce Mini-Park was financed by the Forward Thrust series of bond initiatives that were approved by voters. According to author, historian, and political activist Shaun Scott’s series of essays on Forward Thrust for The Urbanist, “in the 1968 election, Forward Thrust outperformed among Black Seattleites relative to Seattleites as a whole on every individual measure, and by an overall mean of 8.4%.”

But Forward Thrust’s popularity among Black Seattleites does not mean that their concerns were front and center to what the initiatives entailed. In one of his essays, Scott quotes Dick Page of Forward Thrust’s campaign staff who confessed to Seattle Magazine “our organization never once [asked] ‘what are we going to do for the Negro?’ For every person suggesting we give special preference to the Central District, we had two others claiming that the major problem area was the Green River Valley.”

It is impossible to create a time capsule to go back and examine all of the circumstances that influenced New Hope Missionary Baptist Church to sell its land to the City in 1969, or to create an alternate timeline in which the church held on to the land and did not purchase the other parcel. However, the claim that this particular institution was shut out from the economic growth of the surrounding neighborhood invites questions.

Yet, when you look at the factors that led to the displacement of BIPOC communities in Seattle, it is undeniable that disturbing patterns appear. From the initial seizure of the land on which Seattle sits from the Duwamish, who are still federally unrecognized as a tribe despite having signed the treaty of Point Elliott in 1855, to the forced removal and internment of Japanese Seattleites during World War II, to the construction of both I-5 and the Kingdome in the International District which displaced homes and businesses, to redlining and racist covenants which restricted Jewish and BIPOC Seattleites from living in much of the city for decades, to the aforementioned urban renewal of the 1950’s and 60’s, and finally to Weed and Seed, the destructive anti-crime initiative of 1990’s that resulted in the asset forfeiture of people’s homes, notably Black Seattleites in the Central District, many examples exist. This list is long, but it is also incomplete.

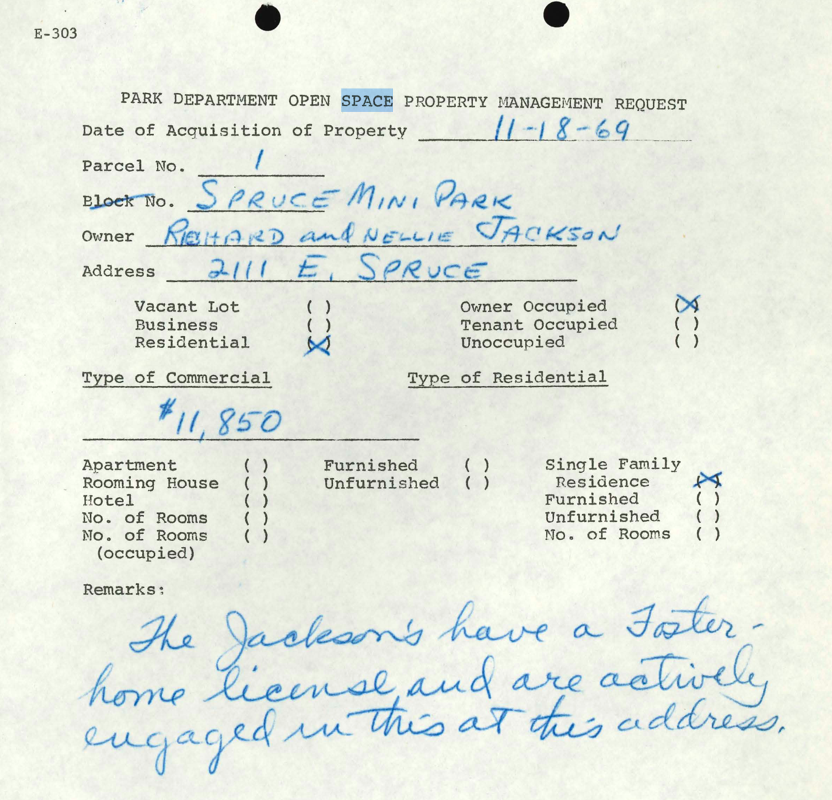

Some injustices are writ-large, like the case of the Yesler-Atlantic urban renewal project which displaced hundreds of families. Yet, sometimes it is the small examples that bring most vividly to life the hardships people have faced. Take for example, the case of Spruce Mini Park. About half of the park’s land is below street level, serving to help drain rainwater runoff away from the surrounding area, which includes a childcare center that has been in operation since 1963 and is separated from the park by a cement retaining wall. However, although never an ideal spot for buildings, before the land became a park, it was the site of people’s homes. One of the letters of acquisition from the City provides insight into past inhabitants, an “actively engaged” foster family, Richard and Nellie Jackson.

When approached by the City to sell the land, could the Jacksons have felt relieved to receive compensation for land in a low lying area? Or did they feel coerced to give up their home and cheated by the payment they received? Were they able to find another home to continue fostering youth in?

Understanding and quantifying these damages is a tall order. But if Seattle and countless other American cities want to write a new, more socially just chapter of their history, it is work that needs to be done. During a speech, Rev. Jeffrey put it well when he explained why the City needs to invest in paying reparations to Seattle residents that have faced discrimination. “You cannot build a stable future on a crooked foundation,” he said. “Just as we are here today asking to correct the wrongs that happened in 1969, there will be others here, standing in this place, standing in other places, to correct the injustices that are not corrected today.”

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.