In July, the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) released their draft three-pronged Regional Housing Strategy (RHS). The strategy is to be a collection of regional and local measures to preserve, improve, and expand the region’s housing inventory. It hopes to encourage fair and equal access to housing for the region’s residents with a range of affordable, accessible, healthy, and safe housing options. Work on the strategy kicked off in winter 2020 and will be finalized this fall.

So, how does the RHS fit into the catalog of planning policies that the Puget Sound region’s jurisdictions use? This document primarily acts as support and a resource for the region’s many housing actors and future housing planning actions. The strategy is meant to support Washington’s Growth Management Act and PSRC’s (King, Kitsap, Pierce, and Snohomish Counties) Vision 2050 that both help direct the four-county region’s growth. It also provides a coordinated, data informed, and ambitious framework that supports all levels of government to meet current and future market-rate and affordable housing needs.

The problem the strategy aims to ameliorate involves the current affordability and supply challenges, and the historic housing wrongs and their reverberations that include housing discrimination and today’s displacement dilemma. The issues are amplified by the region being two years behind in housing production and deficient in affordable housing. The strategy details the use of housing as a way to create great inequities in wealth, ownership, and opportunity and as a way to start repairs on the historical and continuing racial/income divide. PSRC aims to provide this redress with a litany of measures that can be categorized into three pillars: supply, stability, and subsidy.

Supply

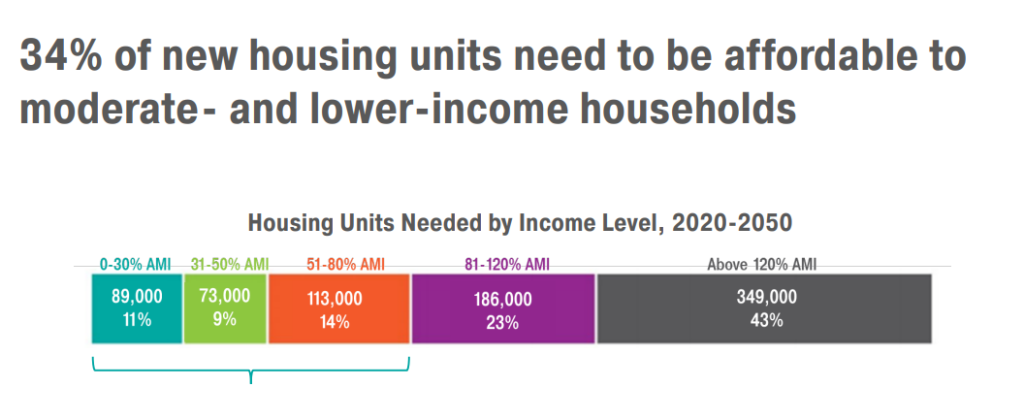

The Regional Housing Strategy’s call for more supply is only natural in a region with both a fast-growing population and a severe housing shortage. To accommodate an estimated population of 5.8 million people by 2050, the four-county Puget Sound region will need over 800,000 new housing units, based on PRSC projections. To meet this demand, the PSRC is calling for a major reexamination of the region’s zoning. The recommendations fall in line with the calls of a typical housing advocate, urging localities to upend or further liberalize existing zoning.

First, the RHS emphasizes the role they want to see transit-oriented development (TOD) playing in the region’s housing inventory. The strategy wants 65% of residential growth to be located near high-capacity transit stations with increased opportunity for moderate and high-density housing. That’s roughly 526,500 new housing units by King, Pierce, and Snohomish County’s bus rapid transit, light rail, and other capacity transit stations.

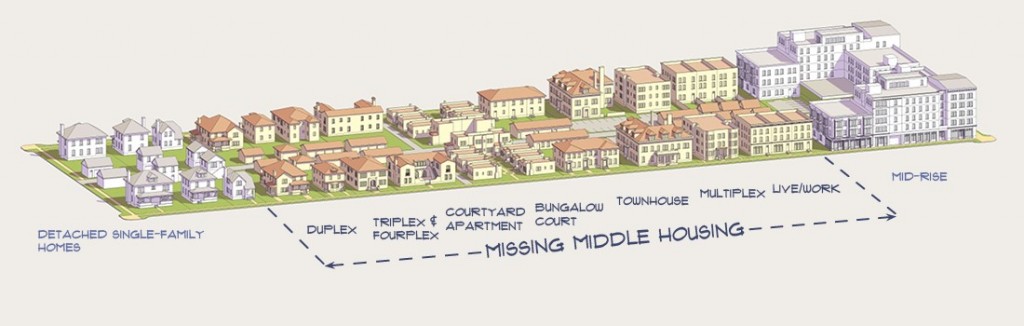

Less intensive upzoning measures include increasing moderate “missing middle” housing density areas and reforming single-family zones. These two changes are thought to be the best for affordability and supply. Moderate density zoning supports a more diverse catalog of housing options for residents, and also tends to be more affordable compared to low- or high-density housing options. Since large-lot single-family zoning is dominant throughout the region, changes to the strict low-intensity zoning could yield significant regional impact. Though the RHS only mentions reforms to possibly increase opportunity for small lots, zero-lot-lines, accessory dwelling units, and duplexes.

While transportation is not the domain of the RHS, the focus on TOD could prove as a way to shield much of the low-density single-family housing in the region. When considering the slow pace and potentially even slower pace that our high-capacity transit is being built, it’s slightly disconcerting to see the separation of missing middle legalization and single-family zone reform in the strategy document. Accessory dwelling units and duplexes are not the bold reforms that we need to see to combat the region’s supply and affordability crisis.

Outside of zoning, the RHS also wants to help lower construction costs to boost housing construction rates and improve affordability. Already mentioned measures like reduced minimum lot size, increased density, and reduced or eliminated parking requirements all make it less costly to build. The strategy also details increased development predictability by way of increased regulatory consistency and reduced complexity, as a way to lower costs. This would require cross-jurisdiction and agency cooperation, but the PSRC has found that developers report complexity of varying regulations, increasing costs for housing

Stability

The stabilizing prong of the RHS focuses on allowing people to remain in their communities and also improve their quality of life. The category aims to protect tenants and potentially turn them into homeowners. The first measure for stability that the RHS calls for is strengthening tenant assistance and protections by providing tenant counseling, assistance, and landlord education for fair, safe, and healthy housing. It wants cities and agencies to provide assistance and education, and to ensure affordable housing meets basic health and safety standards.

To increase access to homeownership, the RHS wants to see advocacy for a bill to support equitable homeownership assistance for tenants seeking to buy a home in their community with down payment assistance programs. The PSRC finds that often renters are able to afford the monthly costs of a mortgage, but are unable to make a down payment at the region’s current housing costs. The strategy points toward past success of low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans at increasing homeownership. The agency would like to see these tools in a modern federal program.

Stability through opportunity is also called for by the RHS. The strategy hopes to achieve this with increased services and amenities in low opportunity areas, and the creation and preservation of long-term affordable units near transit and higher opportunity areas. It calls for local bodies to incentivize early childhood education, medical care, and other community commercial use in mixed-used development. These services are also under threat of displacement, so development of more commercial spaces via mixed-use buildings are called for.

Additionally, as the opportunity of high-capacity transit does attract development and the PSRC calls for most of the region’s residential growth in high-capacity transit areas, residents in those areas are more susceptible to displacement. The strategy calls for voluntary or mandatory incentives to include affordable housing in all new development in proximity to transit and other high opportunity areas. One incentive is multifamily tax exemptions, which have been a major factor in creating housing for those earning less than 80% of the area median income (AMI). For example, much of Shoreline’s more affordable developments have used the city’s multifamily tax exemption program.

Subsidy

When discussing subsidy as the last prong of the RHS, market-rate housing is acknowledged as the largest source of new housing. The increasing market-rate housing supply does help slow the worsening housing affordability crisis in our region, as housing supply studies have supported. However, it is clear from the research and PSRC’s understanding of housing supply that the private market can’t provide housing or much relief to those with the lowest incomes. The housing strategy notes that the region can’t fully address its affordability crisis until housing needs of extremely low-income (less than 30% AMI) households are met.

To meet those needs, PSRC calls for intervention by the region’s public bodies to identify public, private, and philanthropic funding to increase affordable housing inventory and access. The strategy calls for advocacy and expansion of funding from all levels of government. Rental assistance for very low-income households and building more affordable housing would be top of mind for federal and state funding advocacy. Locally, the RHS does point out that a housing levy or increasing general funds toward housing may be challenging. However, it also states that local funds have played a major role in getting “matching” funds from other sources. For small jurisdictions that can’t raise significant funds of their own, the RHS proposes raising housing funding with a multi-jurisdictional housing body.

Mention of private financing and philanthropy is also included in the RHS, as there is a moral and even economic responsibility of private firms to spend on affordable housing. Housing options, affordability, and even a moral facade can help firms recruit in an increasing competitive environment. Private financing and funds for affordable homes have already been committed recently, but this largely has come in the form of below-market loans. Combined, roughly 8,900 affordable units in the region will be made available from Microsoft and Amazon’s loans. Local jurisdictions and housing organizations are also called to facilitate continued corporate involvement.

Implementation, Monitoring, and Outlook

To implement this strategy, PSRC needs responsible local governments to act. Both capacity and accountability are needed to meet our housing needs, as jurisdictions are typically either incapable or unwilling to meet development needs when they can or do not meet GMA requirements. However, there are no excuses for not meeting housing needs. Regional housing agencies have been used to help cities with less resources in each county implement the RHS. Accountability is outside the realm of the PSRC’s power for housing, but the regional council can provide incentives for cities to implement the RHS.

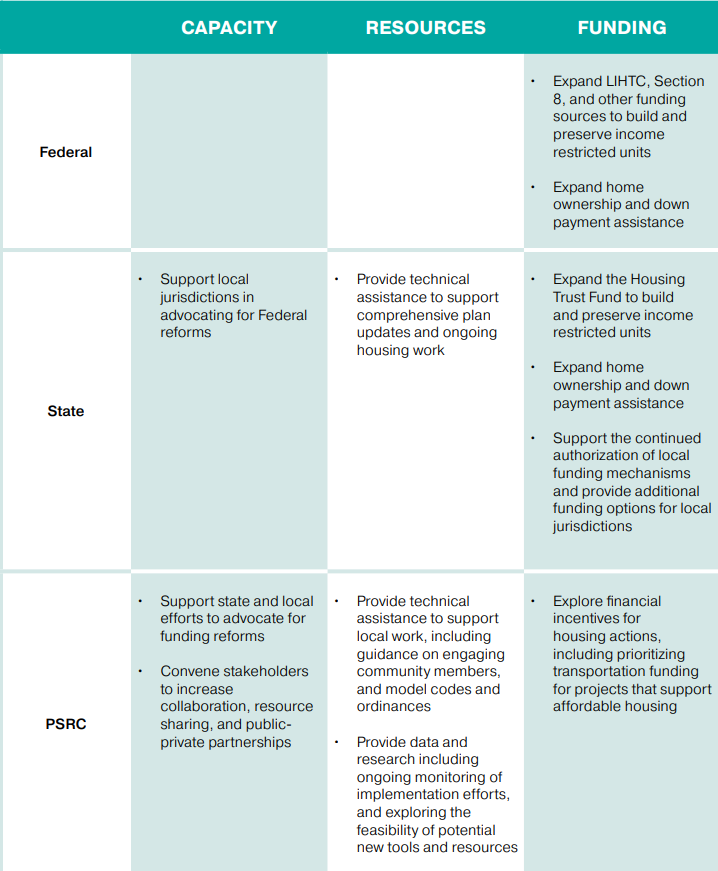

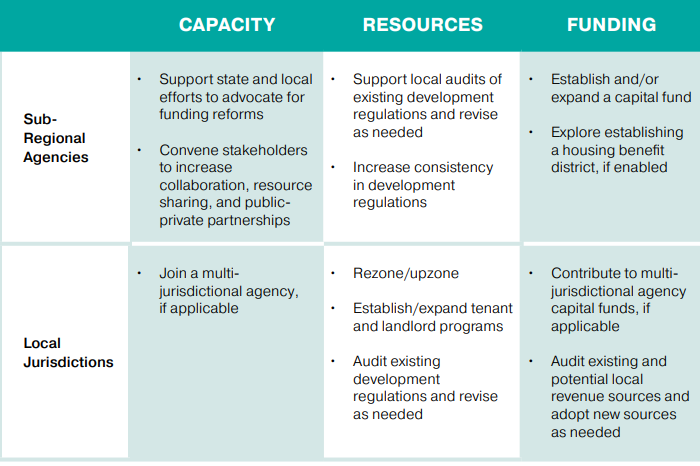

PSRC also put together a chart of what each level of government can do to meet the region’s housing and affordability needs. The chart follows:

PSRC is also taking steps to measure the changes in our housing inventory to help keep track of their goals. The regional council has committed to developing a framework to track performance and identify challenges. This monitoring will also be made shareable for the region’s many jurisdictions. It will also hopefully find that we’re on our way to over 810,000 new units, of which 89,000 new units would be affordable to those earning 0% to 30% AMI, to avoid continuing the current crisis. Getting there will be a slog, but it’s critically important for the region to at least keep pace with its housing needs.

The draft puts it best when concluding with the stakes of our housing crisis:

Housing is critical for every resident, and every community plays a role in addressing this collective responsibility. The complexity of addressing the full range of housing needs and challenges requires a coordinated regional-local approach and will require action from cities, counties, residents, businesses, and other agencies and stakeholders to work together to meet the needs. A coordinated, regionwide effort to build and preserve housing accessible to all residents is not just about housing. It is also about building healthy, complete, and welcoming communities where all families and people, regardless of income, race, family size or need, are able to live near good schools, transit, employment opportunities, and open space.

Draft RHS conclusion (Courtesy of PSRC)

Optimism aside, this strategy only works if every single measure is taken upon by most of the local governments in the Puget Sound. Increased market-rate housing supply alone begets displacement and affordability issues for those with the lowest incomes. Non-compliant local governments can push the burden on others and keep the region in a housing shortage. Even fully executed, the strategy preserves much of the low-density sprawl that is responsible for much of the region’s emissions. Additionally, the state could’ve undershot the 2050 population estimate, keeping the region in the housing crisis it finds itself in right now.

Ideally, the Puget Sound region could have much more liberalized zoning laws, robust tenant rights, and a large pool of public funds for social housing. That way both private market developers and public authorities could swiftly react to demand increases in either market-rate or affordable housing. Maybe displacement could be voluntary. Perhaps the region could even have surplus housing to increase affordability and cushion Puget Sound from demand spikes. But region doesn’t live in that kind of political environment yet, so keep pushing for the pro-housing docket.

A list of upcoming pro-housing opportunities by Share The Cities details what you could participate in soon.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.