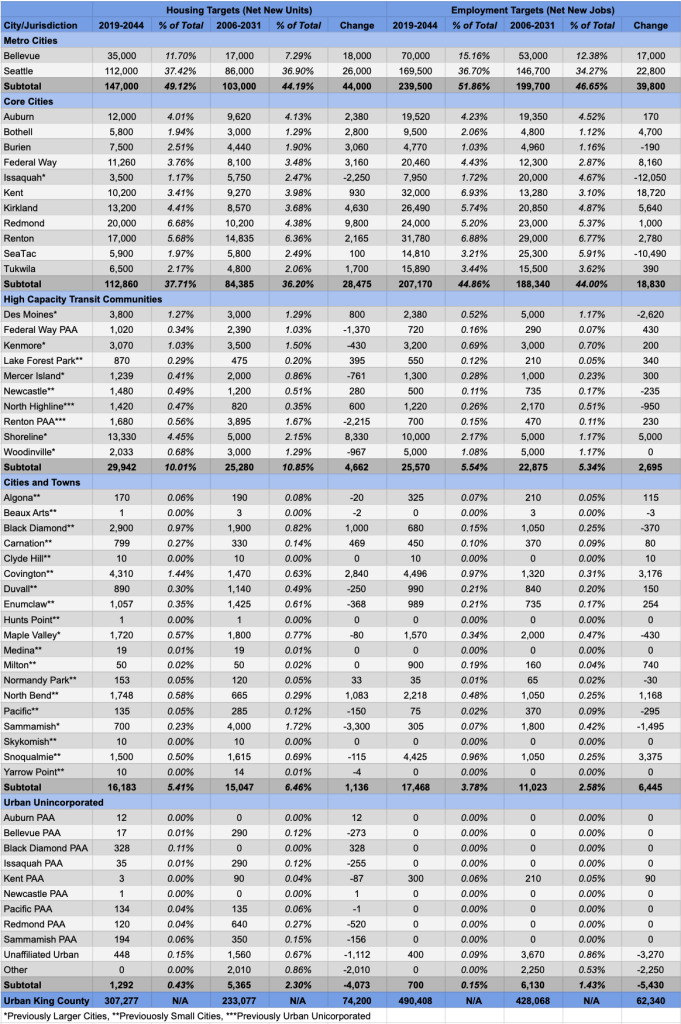

The future of jobs and housing growth in King County has been set. In late June, an obscure regional body known as the Growth Management Planning Council (GMPC) adopted updated Countywide Planning Policies (CPPs). These policies lay the groundwork for growth targets that local municipalities must use to plan for additional growth as part of their Comprehensive Plan updates and ongoing work plans. In this case, the CPPs have been revised with growth targets looking out to 2044. Throughout the county, urban areas will need to accommodate 307,277 net new housing units — including 263,000 net new affordable housing units — and 490,408 net new jobs. There’s no doubt that some aspects of these targets will be a heavy lift for the county and individual municipalities.

Seattle and Bellevue growth targets

The planning horizon for the new growth targets is 25 years, but when viewed through the window of the next major update to local Comprehensive Plans in 2024 will amount to 20 remaining years. Local municipalities will need to plan for the remaining growth targets, largely through updated policies and increases in development capacity, such as rezones and changes to development standards.

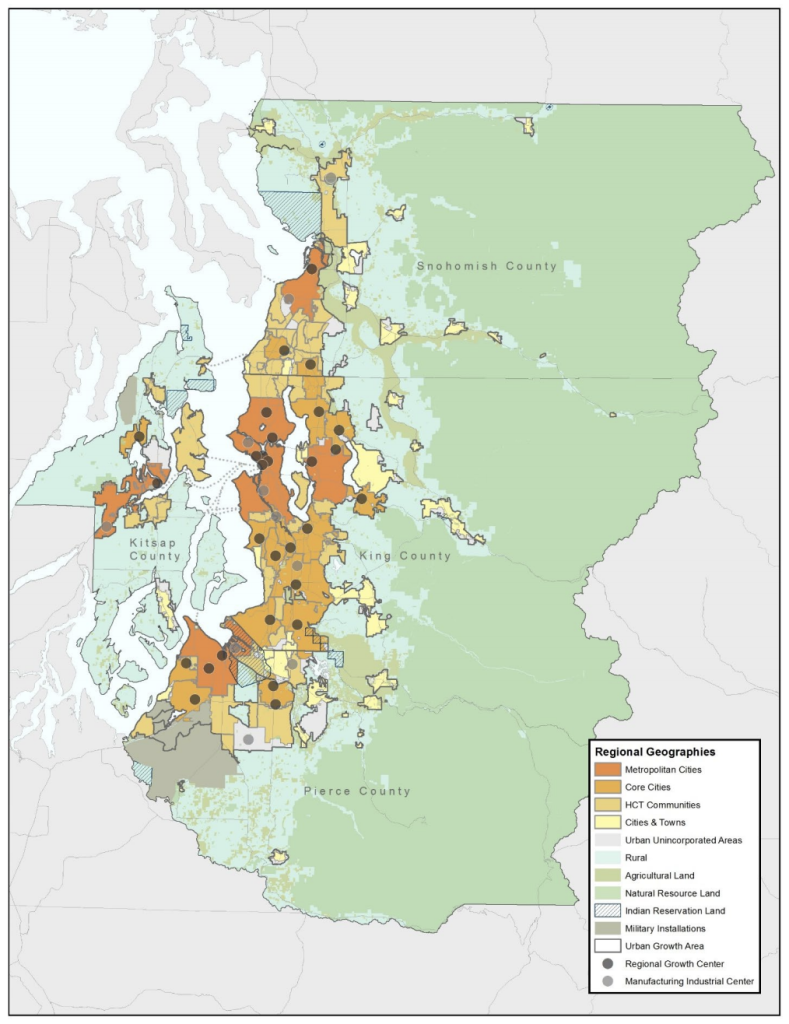

The cities with the highest growth targets are Seattle and Bellevue, accounting for over 49% of net new housing units and 51% of net new jobs. Both municipalities are designated as Metro Cities — the most prominent urban geography identified by the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) — which are supposed to act as major poles for growth and investment in the region. Outside of King County, there are three other Metro Cities in Pierce, Snohomish, and Kitsap Counties — Tacoma, Everett, and Bremerton, respectively.

In King County, Metro Cities are expected to accommodate 381,000 net new residents and 311,000 net new jobs under VISION 2050, which runs to the year 2050. Meanwhile, King County is expected to plan more broadly for 866,000 net new residents and 679,000 net new jobs in urban areas. Note that net new residents is converted into housing requirements by assuming typical household sizes when setting targets for housing growth by jurisdiction.

Seattle is supposed to accommodate at least 112,000 net new housing units and 146,700 net new jobs. This is higher than the previous planning period from 2006 to 2031 when the city’s targets were 86,000 net new housing units (26,000 fewer than the new target) and 146,700 net new jobs (22,800 fewer than the new target). Seattle alone is set to carry over 37% of all new housing units and nearly 52% of all new jobs in the county under the targets.

Bellevue is also supposed to play a larger role in growth than it has in the past. An amendment to what was a draft plan directed the city to plan for 35,000 net new housing units instead of 27,000 and 70,000 net new jobs instead of 54,000. Like Seattle, this is all higher than the prior planning period from 2006 to 2031 when only 17,000 net new housing units (18,000 fewer than the new target) and 53,000 net new jobs (17,000 fewer than the new target) were called for. The additional targets for housing are significant, more than doubling the 25-year goal over the previous planning period. The city could end up shouldering about 7.3% of all net new housing units and 12.4% of all net new jobs in the county under the growth targets.

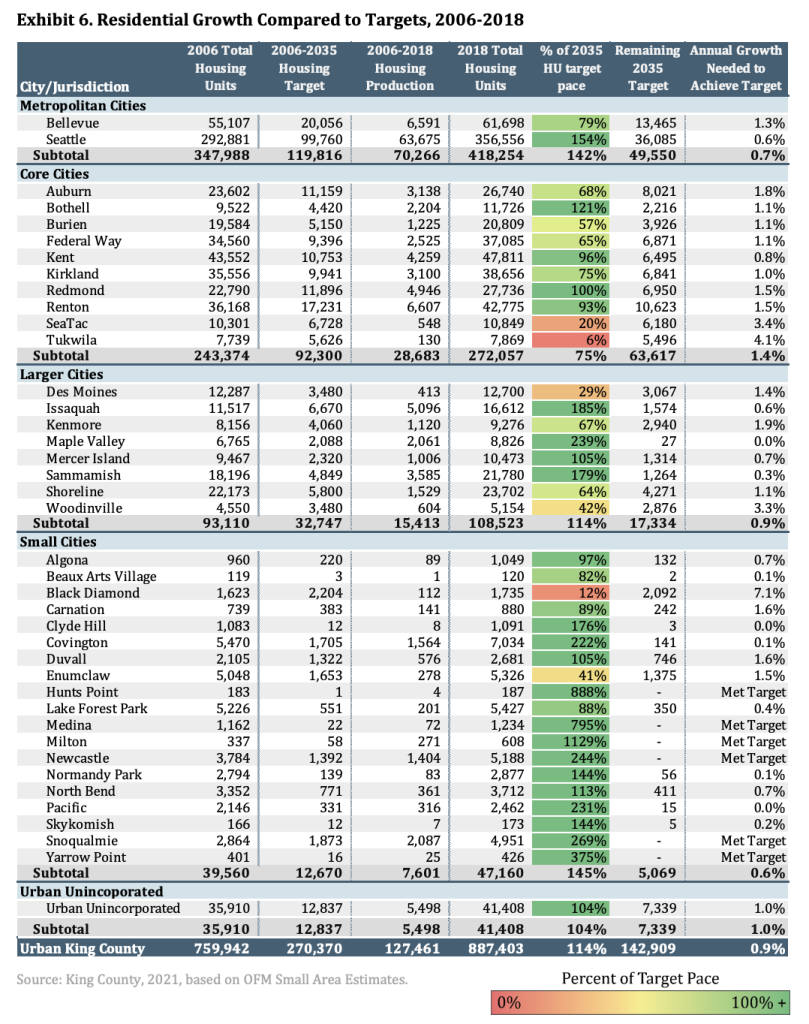

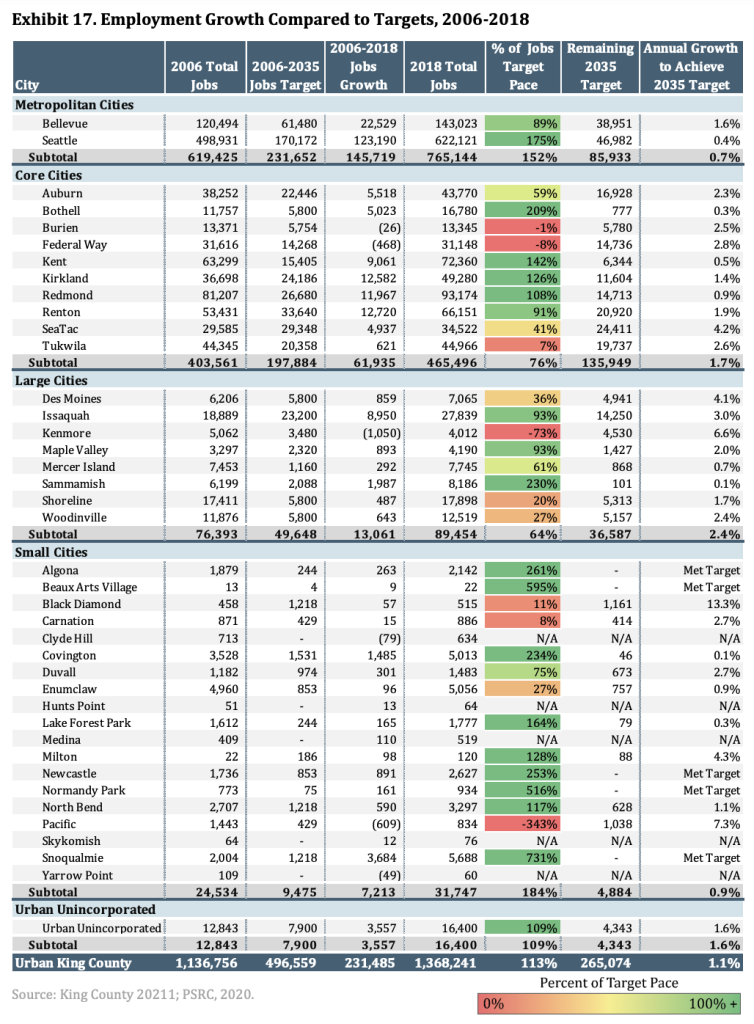

Bellevue, however, has been a poor performer when it comes to achieving its growth targets — especially for housing — when compared to its peer city, Seattle. Based upon data from 2018, Bellevue was on pace to miss its very modest housing targets for 2035 by 21%, having only produced 6,591 net new housing units between 2006 and 2018. Meanwhile, Seattle had produced nearly ten times the number with 63,675 net new housing units. That ambitious level of housing growth has put Seattle on pace to hit 154% of the city’s housing targets by 2035 with only 36,085 net new housing units to go — a number that the city could surpass early this decade or may have already.

Bellevue has performed better on the net new jobs front reaching 22,529 in 2018. But the city still came up short on the pace by 11%. The city will need to accelerate the pace a bit if it’s to achieve the 2035 targets and it may have already with big investments in new jobs by Amazon, which has all but made the city its actual HQ2. Seattle, however, still out-punched Bellevue by miles.

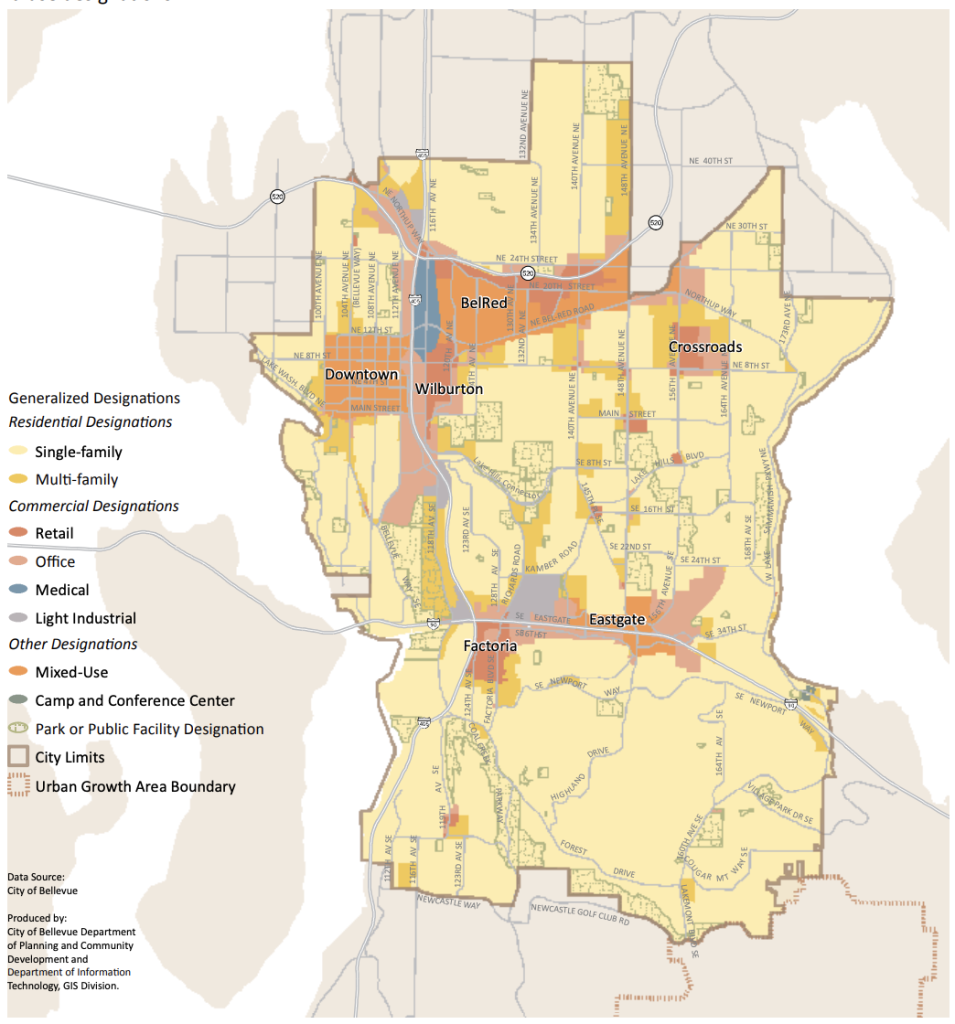

What’s most striking about the two cities, however, is just how low Bellevue has set its sights on housing. The allocated housing targets are exceedingly modest for a city that wants to grow as a major center of business, despite the amendment more than doubling the housing targets for this go-around. While the jobs-to-housing ratio may be somewhat similar to Seattle, Bellevue has routinely failed to adequately zone for housing and attain development of it. Put another way, the new housing targets don’t try to make up for the past, they merely attempt to bring closer parity of the jobs-to-housing ratio with Seattle. Falling as short as Bellevue has in the previous planning period, for instance, is a disastrous and predictable outcome. The city’s zoning map is reflective of just how exclusionary the city has chosen to be, locking housing for millionaires in amber and only attaining paltry amounts of affordable housing for those lucky enough to find it.

While it’s true that Bellevue has tackled zoning in some ways over the past decade, it has put nearly all of its eggs in two small baskets when it comes to new development capacity: Downtown Bellevue and the Spring District. New plans under development will only slightly lift the lid to expand capacity. Recent parking reform in Bellevue took a very narrow lens and wound up in a bizarre legal battle because of an exclusionary community council. Plus, Bellevue City Councilmember Jennifer Robertson recently made dubious excuses as to why the city couldn’t do more to accommodate housing in single-family zones.

It almost seems as if Bellevue city leaders want all the benefits of jobs without any of the responsibility in actually housing people. So in this way, the modest housing targets shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, but it does raise serious equity questions about the CCPs update process that let the county’s second largest city off the hook.

Fortunately though, the adopted CPPs mean that growth targets for Metro Cities and Core Cities are only a baseline target. Cities like Bellevue are explicitly encouraged to exceed them, so zoning for higher development capacity should be a city policy. But will Bellevue leaders seize the moment? It’s hard to imagine that right now.

Other urban geographies growth targets

Turning to other urban geographies in the county in brief, there are four types besides Metro Cities. These include Core Cities, High Capacity Transit Communities, Cities and Towns, and Urban Unincorporated, which cover cities, towns, and other urban areas. Some of these were reclassifications as part of the PSRC’s VISION 2050 update, which elevated select municipalities for more growth as high-quality transit expands in the region.

Core Cities include places like Kent, Auburn, and Redmond. Many of these cities are well served by key transportation corridors and substantially sized in geographic area. Core Cities are slated to grow by another 112,860 net new housing units (more than 37% of the countywide target) and 207,170 net new jobs (more than 44% of the countywide target).

High-Capacity Transit Communities tend to be smaller cities but still served — or planned to be — by high quality light rail and bus rapid transit services. Cities in this group include Mercer Island, Shoreline, Des Moines, and larger potential annexation areas like White Center (North Highline). They get the next largest allocation of jobs and housing with 29,942 net new housing units (more than 10% of the countywide target) and 25,570 net new jobs (more than 5% of the countywide target).

Cities and Towns as well as Urban Unincorporated round out the rest of the cities and urban geographies. These include places like Clyde Hill, Algona, Sammamish, and various small potential annexation areas to cities. Among these places, they are set to get at least 17,475 net new housing units (more than 5% of the countywide target) and 18,168 net new jobs (more than 3% of the countywide target).

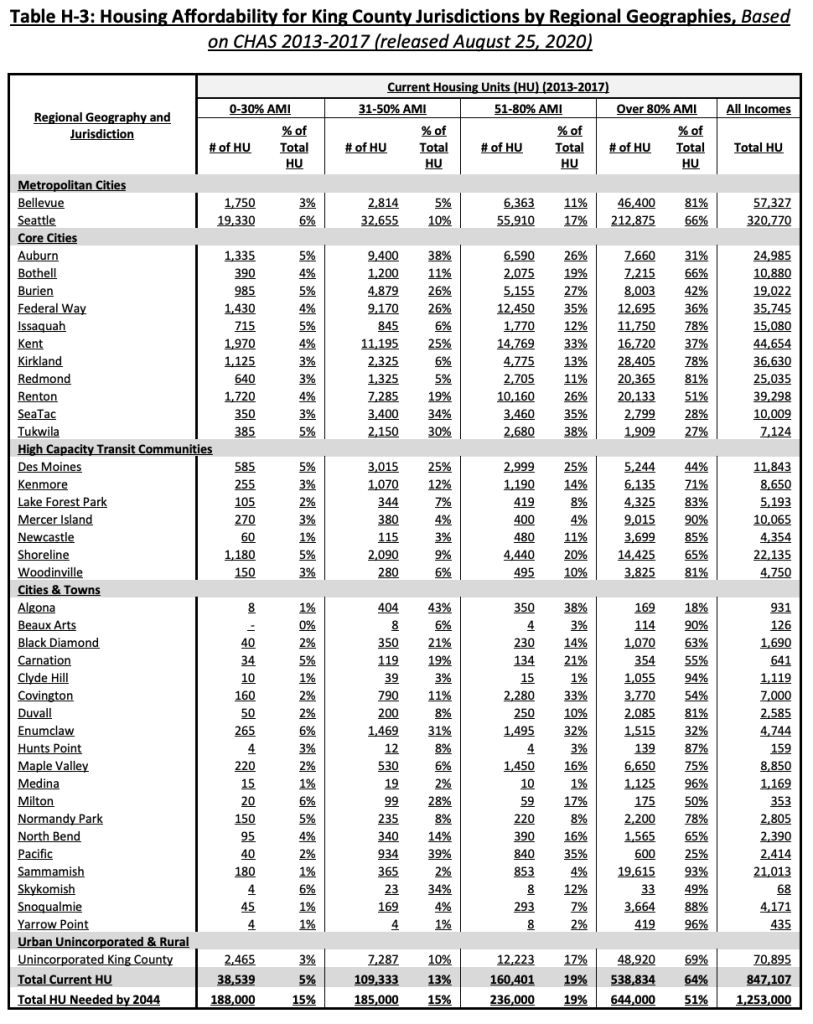

Affordable housing targets

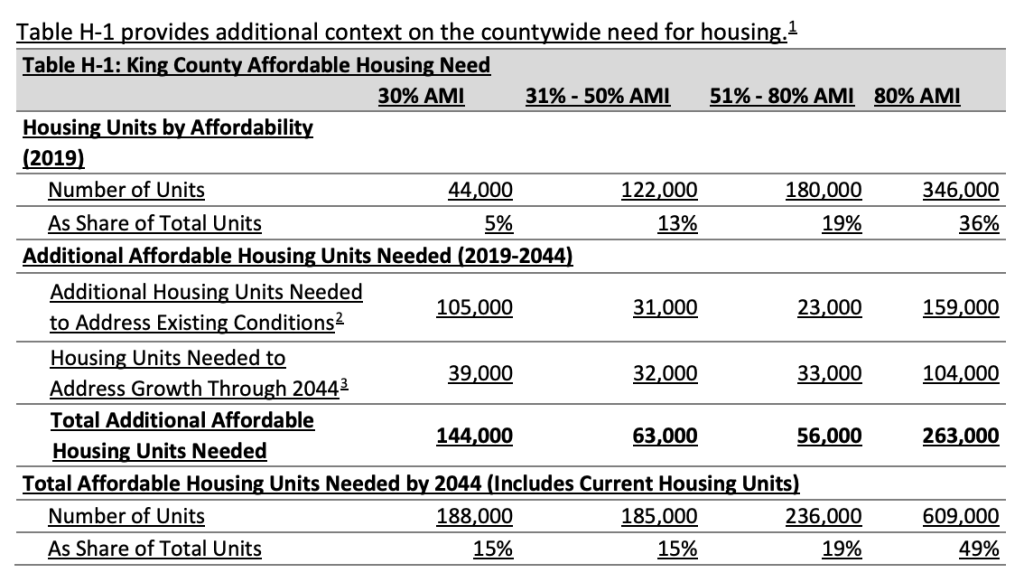

Related to the growth targets, the county also adopted general affordable housing targets by area median income (AMI) level. Over 263,000 new affordable housing units at or below 80% AMI are needed through 2044, including 159,000 units to meet existing conditions. All cities will need to track and plan for affordable housing consistent with the CPPs, which were extensively updated on the topic with many new policies and goals.

The CPPs, however, don’t establish net new AMI housing targets by jurisdiction like the general housing growth targets do. This was left for another day by the GMPC since there was some debate on how to do this fairly. Some areas are naturally more affordable in the county like Enumclaw and Kent, for instance. Time in the update process to nail down precise numbers also was running short, so this will likely come back, as a separate group works through the issue for the GMPC. Still, this is highly concerning given that there is an affordable housing emergency in King County and Puget Sound generally. Cities like Bellevue, Mercer Island, and Medina have not carried their weight despite their extreme wealth, leaving that mostly to Seattle to address single-handedly.

The Metropolitan King County Council still needs to ratify the GMPC’s proposed CPPs, which should come soon. And then local municipalities will need to do the same, but the changes are virtually a done deal.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.