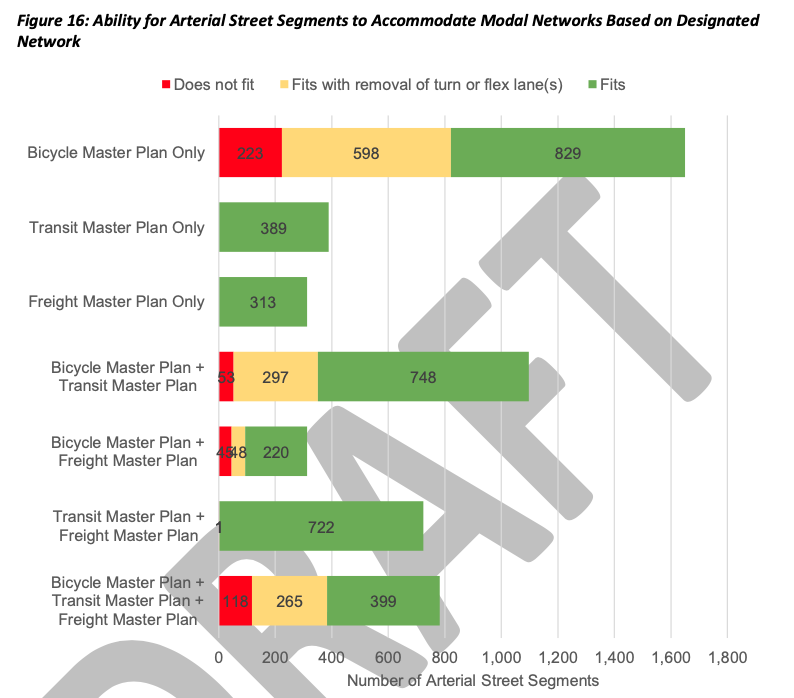

Seattle’s 2013 Bicycle Master Plan is by far the most ambitious of Seattle’s approved multimodal plans. If it were entirely built out, a random sample of one hundred blocks in the city would include twenty-two blocks of protected bike lanes or neighborhood greenways. Contrast that with only nine blocks out of that same hundred that would occupy part of Seattle’s freight network, and thirteen blocks for the frequent transit network. But there’s another imbalance as well: the bicycle network is the only one that occupies both neighborhood streets and busy arterials. The frequent transit network occupies 46% of all of the arterial blocks in town, and the freight network 32%; neither occupy any neighborhood streets. The fully built-out bike network only would take up 20% of the arterial blocks, with many more blocks on residential streets of which there are much more in quantity.

These imbalances are one big reason that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is continuing to push ahead on a plan to integrate all of its siloed modal plans together. But the framework being proposed would create a new bike network map, elevated in importance above the other connections, in which specific segments are deemed “critical,” essentially dismantling that ambitious bike network as envisioned in the Bicycle Master Plan (BMP).

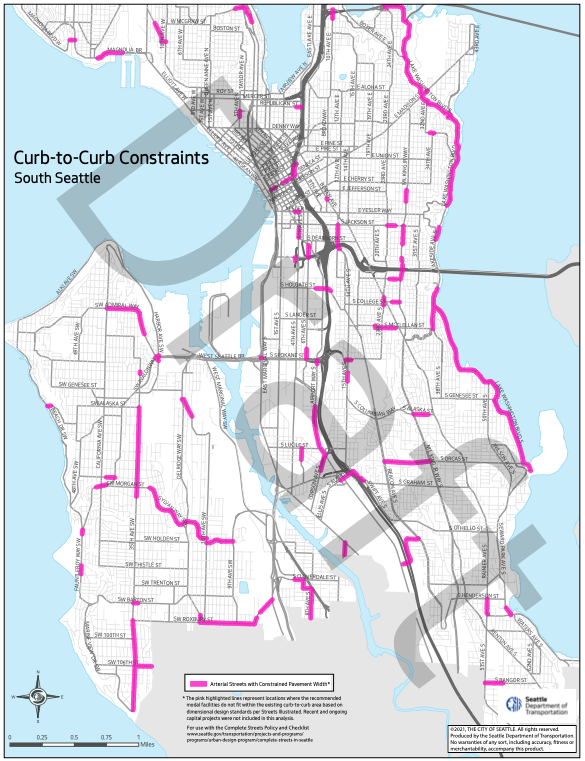

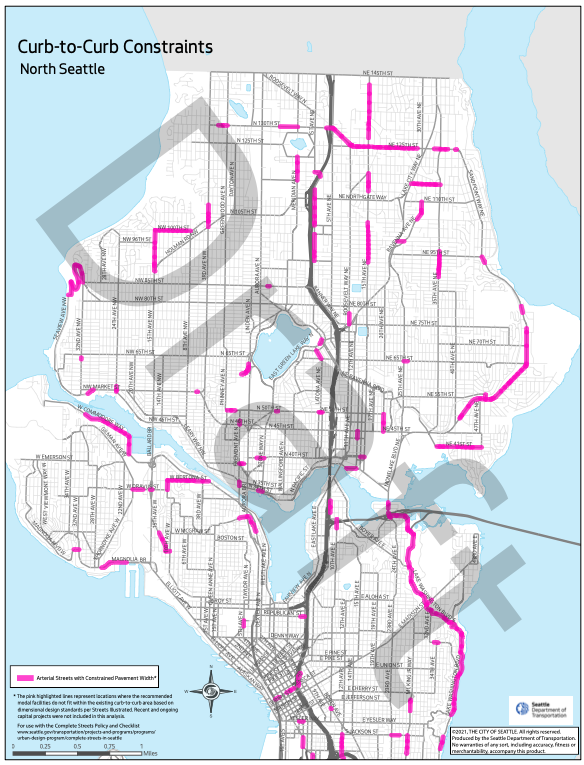

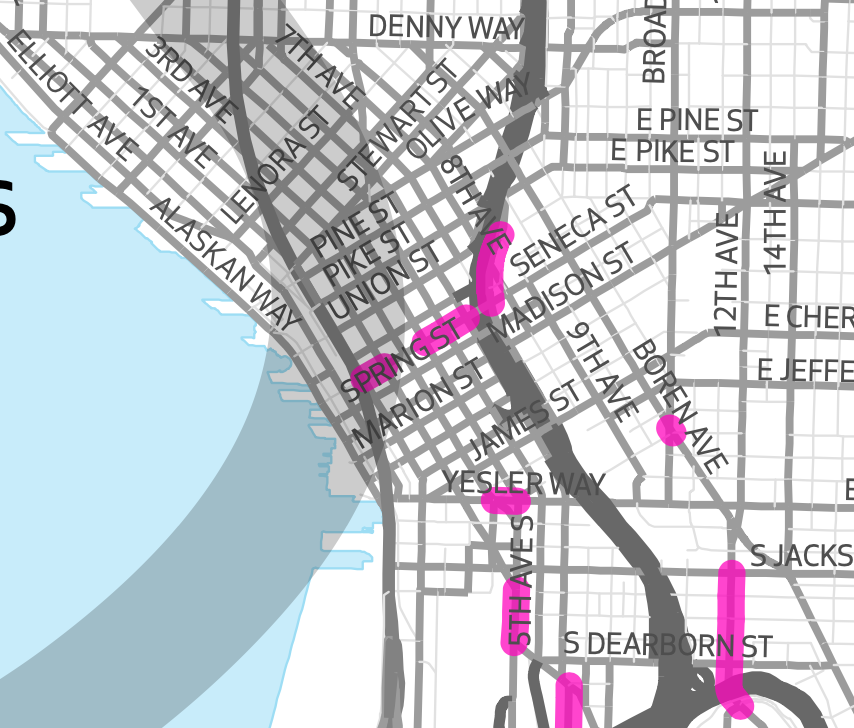

Where this most matters, according to SDOT, is at spots in the street network where there isn’t enough room to physically fit everything. Trying to fit a transit lane, a freight lane, and a protected bike lane onto one block, there might just not be enough space to get everything in there. SDOT has mapped these “deficient” streets and found that there are 440 arterial blocks, or around 8% of the 5,269 blocks with planned modal networks, where the roadway width is too narrow. SDOT has now released maps of all these segments in a newly released white paper on their proposed integration policy, and these maps underscore just how separate the fact of physical constraints is from the very political issue of where the City prioritizes certain modes.

In Downtown Seattle, for example, where jostling over street space can be at its most intense, almost no streets are highlighted as being physically constrained: a few stretches of Seneca Street and a swath of Hubbell Place next to Freeway Park, envisioned as having a protected bike lane in the BMP. 4th Avenue, where Mayor Jenny Durkan held off on green lighting a protected bike lane that was ready to be built when she took office, doesn’t register.

Most of Rainier Avenue is also, incredibly, not highlighted as lacking physical space for all the modes with claims on it. Nor is Eastlake Avenue, one of the recent rare instances of intense disagreement over the allocation of street space where bike lanes have been prioritized. A protected bike lane recently built on 12th Ave S across the José Rizal Bridge to Beacon Hill doesn’t run north of King Street due to concerns over traffic impacts to transit, but the constraint map actually shows that it’s the stretch across the bridge where space is tightest.

On the other hand, Lake Washington Boulevard stands out like a sore thumb, illustrating another limitation in this analysis: an assumption baked into the process is that no arterial street segment would see general-purpose vehicle lanes entirely removed, so a narrow street with two lanes currently like Lake Washington Boulevard can’t accommodate any changes. Clearly any changes to this street, like the ones being tried out now with a weekend summer pilot project, would reflect the context of uses along it. Knowing that a traditional protected bike lane doesn’t fit here doesn’t really help anything, and that’s a fact that will be true at many of the other stretches of street where right-of-way is “deficient.”

At last week’s Bicycle Advisory Board meeting, Jonathan Lewis of SDOT, who has been working on the policy, steered the board away from discussion of specific segments of the map and noted that the map should primarily be used to understand the “scale of the problem.” I think this is right, and that the map illustrates the scale of our problem accommodating mode prioritization is almost entirely political and not geometric. When the subject of removal of general-purpose lanes as an alternate parameter to be studied was brought up, Lewis responded that such a change would likely be considered on a case-by-case basis — an answer that is true generally everywhere.

In addition to the 8% of arterial streets that SDOT says aren’t wide enough to accommodate all modes, there is another 23% that will accommodate the modes designated for them only if a turn lane, parking lane, or loading zone is removed. That is over 1,200 additional blocks of additional case-by-case analysis that will still be needed to determine how to prioritize in the best way; in many cases parking lanes can be removed to accommodate more efficient travel, but in some cases turn lanes and loading zones may need to be retained. For nearly 600 of these blocks SDOT says the only mode to be prioritized over the parking or turn lane is a bicycle facility. This underscores the pressures that exist to create a scaled-back version of the bike network that wouldn’t have such an appetite for parking removal.

What about the Pedestrian Master Plan? SDOT also analyzed the space between property lines, as opposed to curbs, to analyze spots where sidewalks are not up to standards. Their analysis only found around 6% of sidewalks along arterials in the City were more than three feet shorter than current standards, with 40% of those sidewalks inside urban villages and centers. This doesn’t include the nearly 2,000 blocks in Seattle along arterials that don’t have sidewalks at all. In most cases prioritizing expanding existing sidewalks isn’t going to happen, as the city focuses on the long (and impossible given current funding) task of completing the existing sidewalk network. But the white paper includes a welcome acknowledgement that the current Pedestrian Master Plan, focused on adding sidewalks and crossing improvements, “is missing a pedestrian-oriented map that prioritizes the creation, improvement, and management of public spaces, and special areas in the right-of-way.”

As for the proposed dismantling of the Bicycle Master Plan, SDOT is still moving ahead with the creation of a map of critical bike connections that will be used in Seattle’s Complete Streets process in advance of being integrated into the overall multimodal transportation plan that is currently on track to go into the City’s Comprehensive Plan update in 2024. The proposed criteria for a critical connection includes routes that have the fewest number of turns, a grade of less than 6%, and are spaced no more than a half-mile apart from one another. But all of the analysis that has been presented so far around this policy demonstrates that there isn’t any need to start systematically prioritizing some routes above others in the first place.

The citywide transportation plan is now heading to a consultant phase, where SDOT will pay $2.7 million to have the plan fully developed in anticipation of the Comprehensive Plan update. The new protected bike lanes along N 34th St in Fremont only cost $1.9 million, according to SDOT’s Capital Projects Dashboard. $2.7 million is a lot of money to create a new plan to tell us what we already know: our main constraints are political, not spatial.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.