Update: Council Bill 120081 was signed into law on by Mayor Durkan on July 9, 2021. Critics are still hoping that the amended law can be repealed. In September 2021, they got their wish, as the Seattle City Council passed a revision easing the affordable threshold to 80% of area median income, as originally drafted.

Critics are demanding a return to the 80% AMI threshold for affordable housing developed on land owned by religious institutions.

It was a long-awaited day, one that was supposed to mark a hopeful new chapter for Seattle’s Black churches, who have endured the frontlines of the city’s skyrocketing housing costs and gentrification. Cash poor, but rich in land, Seattle’s Black churches have been searching for creative ways to use their property to ensure that their communities have a future in a city where the percentage of Black residents has declined to the lowest level in 50 years, even as overall population growth has surged.

But what was supposed to be a day of celebration quickly dissolved into disappointment as church leaders and supporters watched a last-minute amendment alter legislation they had fought for on the state and local level. The legislation, which provides density bonuses (i.e., development capacity increases) to religious institutions seeking to build affordable housing on land they own or control, was supposed to be a way for Black churches to create homes for members of their communities impacted by displacement. But an amendment sponsored by Councilmember Lisa Herbold (District 1, West Seattle) deepening affordability requirements from 80% to 60% or less of area median income (AMI) has stirred up uncertainty.

“The last-minute change is effectively a poison pill, transforming a well-crafted policy to one that excludes those it’s meant to benefit,” wrote Donald King, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Nehemiah Initiative Seattle, in a open letter to City Council President M. Lorena González (At-Large) that calls on the City Council to correct their error and return the bill to its original form.

We support projects that serve the low-income community, but we are aware that they cannot cover their costs of development without heavy subsidy. Only deep pocketed non-profits or experienced developers with access to Federal tax credits can attempt projects like these. Modest Black churches and small BIPOC-led development firms simply cannot build to this level of affordability. The amendment is another action in the decades of well-intentioned measures that do more harm than good to the financial growth and independence of the Black community.

Donald King, President and CEO of the Nehemiah Initiative Seattle

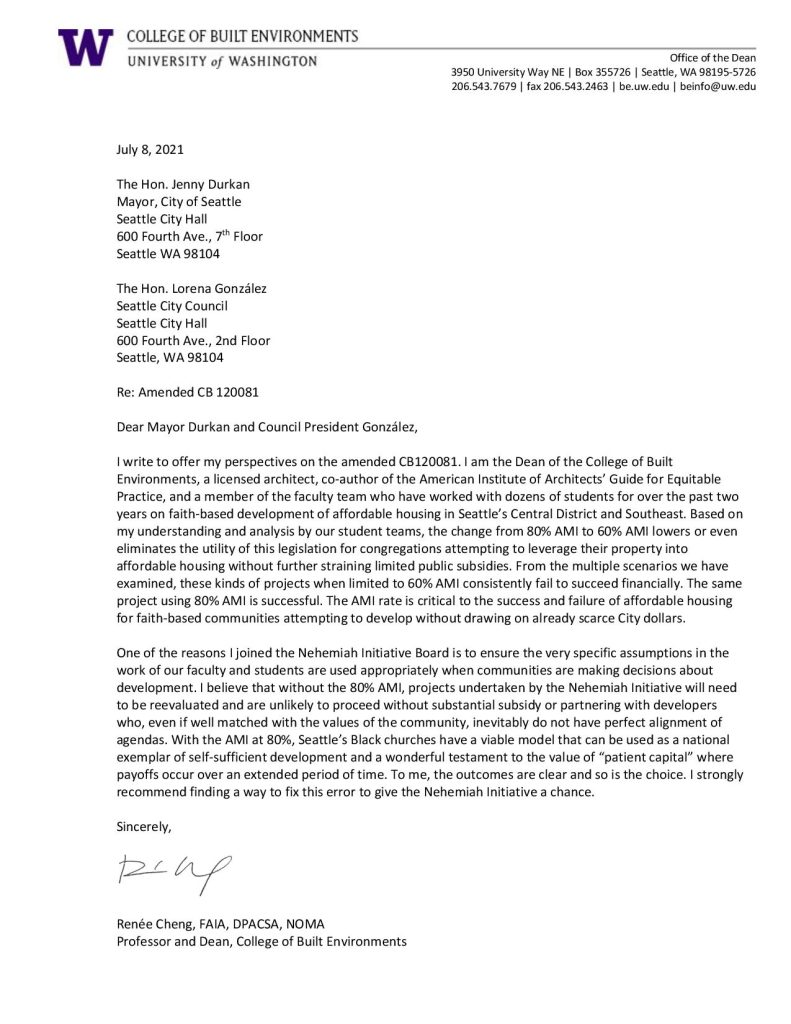

Reverend James P. Broughton III, Senior Pastor of Damascus International Fellowship, located in Rainier Valley, and Renée Cheng, Dean of the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington (UW) and Board Director of the Nehemiah Initiative, have also submitted letters to city leadership expressing disappointment with the amendment and hope that the mistake will be quickly remedied.

“In a crisis defined by scarcity, in a city with limited land available for development, any lost affordable unit is a significant loss. The city cannot turn its back on these faith communities now,” wrote Rev. James P. Broughton III.

A giveaway for religious institutions?

Since the passage of House Bill 1377 one year and a half ago, religious institutions in Seattle have eagerly anticipated the new zoning flexibility the legislation would unlock. “I expect to see an immediate impact,” said Dan Strauss (District 6, Northwest Seattle), who sponsored the council bill. Strauss also urged his fellow council members to approve the bill as written and stood with councilmembers Teresa Mosqueda (At-Large) and Tammy Morales (District 2, Southeast Seattle) to oppose the amendment reducing AMI requirements to 60%.

“I’m happy to come back in a year to analyze the changes,” said Strauss, referencing a desire to first see how the policy performs before amending it.

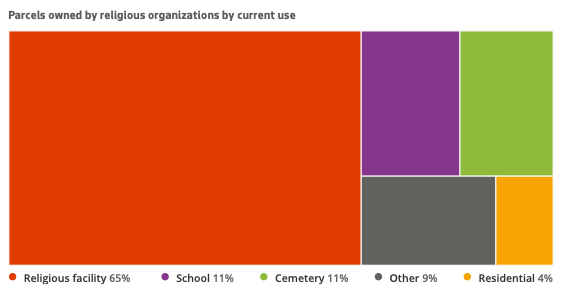

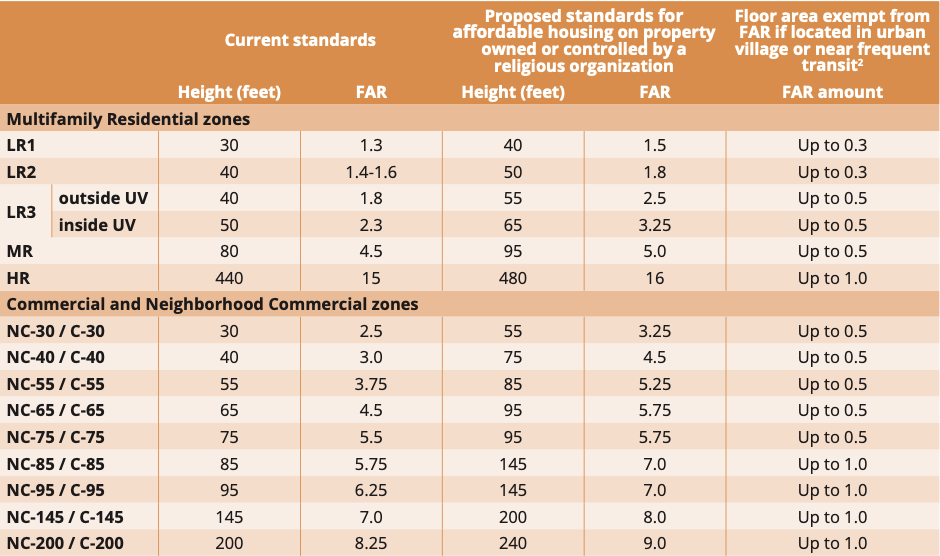

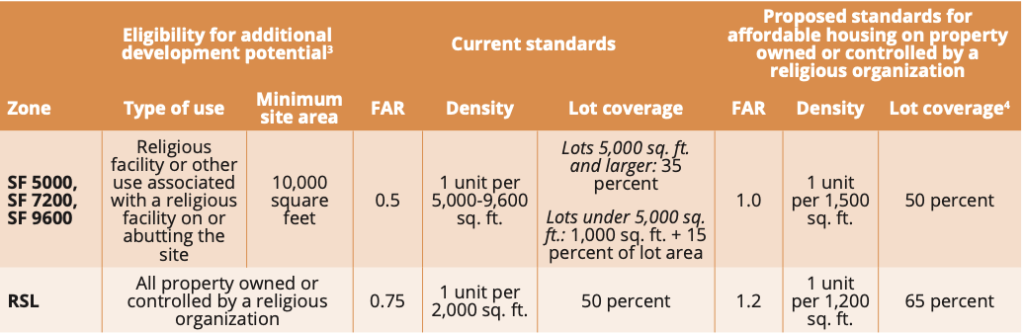

Intended to facilitate the production of affordable housing across Washington State, HB 1377 requires that cities grant density bonuses in the form of increased maximum building heights, density, and/or floor area limits to property owned or controlled by religious institutions in exchange for the development of affordable housing. Groups like the Housing Development Consortium and Greater Church Council of Seattle advocated for the passage of HB 1377, arguing that church-owned and -controlled properties, especially surplus land like underutilized parking lots, were an untapped resource in the fight to expand affordable housing.

HB 1377 allows for cities to tailor the density bonuses to their specific affordable housing needs, but it does put forth a few general rules. As mentioned earlier, any housing created with the density bonus must be affordable to households earning 80% or less of AMI, although cities do have the right to deepen the affordability requirements, as Seattle officials chose to do. Regardless of the AMI selected, future residents may not be charged rents exceeding 30% of their annual incomes.

The affordability restrictions must also be held in place for 50 years, even if the religious institution elects to sell the property during that timeframe. Councilmember Herbold proposed a second amendment expanding the 50-year requirement to 75 years, but that amendment was narrowly voted down with Council President González issuing the decisive vote.

Defending her proposed amendments, Herbold argued that the density bonuses would roughly double the value of the land, and as a result religious institutions should be required to make a contribution to the a public good, in this case, more deeply affordable housing. “As fond as I am of the church council, they are advocating for the interests of the property owners in this case,” said Herbold, asserting that prices at the 80% AMI threshold were comparable to market rate housing prices, a position also held by councilmembers Alex Pedersen (District 4, Northeast Seattle) and Kshama Sawant (District 3, East Central Seattle), both supporters of the amendment.

However, voicing opposition, Councilmember Mosqueda cited the need for more housing at all price levels in Seattle, including at 80% of AMI.

“The fact that rental unit prices are so high is because we do not have enough rental units. It’s not because developers are seeking certain price points. So if we want to address the cost of the rental units, I think one of the best things that we can do through this legislation is increase the amount of rental units in Seattle across the market,” said Mosqueda.

Councilmember Sawant rejected Mosqueda’s supply-side stance, arguing, “At the end of the day, it’s a question of affordability and simply building more does not assure affordability.”

In order to avoid disrupting development plans already in the works, the 60% AMI requirement will not come into effect until July 2022. Additionally, affordable housing projects receiving funding from the City of Seattle already have to meet the 60% AMI requirement per existing policy from the Office of Housing (OH). Ownership housing, which has historically constituted a very small portion of affordable housing built in Seattle, will remain affordable to households earning up to 80% of AMI despite the passage of the amendment.

However, critics believe that even with the lead-in time and other mitigating factors, the deeper affordability requirement will essentially shut out many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) religious institutions from utilizing the legislation.

Why is the 60% AMI requirement seen as such a hurdle?

The desire to build affordable housing on church owned land might be most keenly felt in Seattle’s historically Black Central District, where in recent years efforts like the Nehemiah Initiative and UW partnered Nehemiah Studio have provided technical assistance and support for Black churches seeking to leverage the value of their land to combat community displacement. The initiative estimates that the seven largest Black churches in Seattle alone own over seven acres of property with a total appraised land value exceeding $65 million.

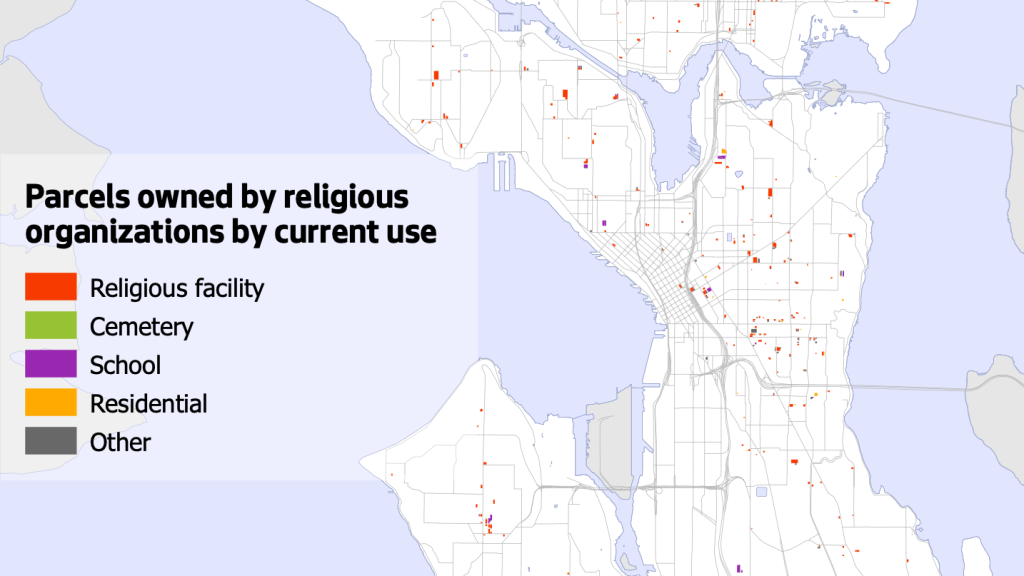

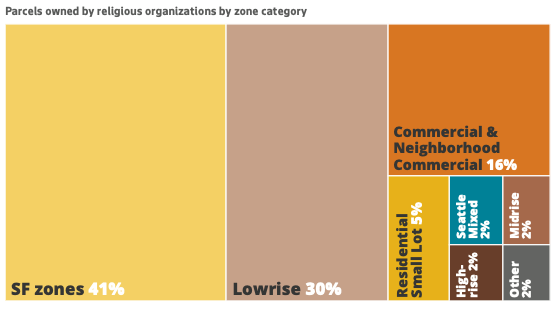

Property owned or controlled by religious institutions can be found in all corners of Seattle, but the Central District has an especially high number of properties located in urban village zones. Roughly 18.1 acres of land owned by religious institutions fall within the boundaries of the 23rd and South Jackson urban village, by far the highest percentage of any urban village in the city. Density bonuses differ based on existing zoning designations and affordable housing constructed in commercial and multifamily residential zones tend to receive the largest density bonuses.

Location can play out well for certain religious institutions. Situated near the core of the bustling 23rd Avenue and Union Street corridor in the Central District, the Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd is an example of a religious institution that would have benefited from the legislation, had it been passed earlier. A community anchor since 1951, Good Shepherd has a history of sharing its space with its neighbors, and most recently this has meant a partnership with Nickelsville and the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI). In fall, the LIHI and Good Shepherd plan to break ground on a seven-story, 92-unit apartment building (68 small efficiency dwelling units, 24 apartments). To arrive at this point, leadership from Good Shepherd and LIHI had to petition for the land to be rezoned, an expensive and time-consuming process.

But while religious institutions can expect to face fewer future hurdles, many other Black churches may never be able to leverage their land as Good Shepherd has. This is especially true for religious institutions whose land falls in single-family and lowrise zones, which have more modest density bonuses. Over 70% of land parcels owned by religious institutions are located in areas of Seattle zoned for lower density.

Still, many Black churches aspire to develop affordable housing on their land, whether located in single family or commercial zones. But research completed in partnership with the UW shows that in most instances affordable housing development will be impossible unless supported with deep levels of financial subsidy from government or nonprofit sources. According to the development scenarios conducted by the UW, the majority of the developments that are financially viable at 80% AMI, simply do not pencil out at 60%, a difference King describes as “stark.”

Our experience and analysis shows that at 80% AMI, a typical church with 5,000 square feet of extra land could build an 18-unit family housing project which would cover its costs and earn about a 4.2% per year yield before interest. The same project targeting 60% AMI would yield only 2.9%. That seems small, until you realize that the churches without massive endowments will need to borrow money at current interest rates around 3.75% per year. The 80% AMI project works — the 60% AMI project goes bankrupt.

Donald King, President/CEO of the Nehemiah Initiative Seattle

In the lead up to the amendment vote, Herbold expressed a desire to steer religious institutions away from partnership with private developers and toward “mission driven nonprofits” like LIHI, whose leadership expressed support for Herbold’s amendment. However, on the opposing side, the Nehemiah Initiative points out that such subsidies are not unlimited and competition can be fierce.

In her letter to Mayor Durkan and Council President González, Renée Cheng points out potential problems that could arise if Black churches are forced to rely on outside subsidies. In addition to funding scarcity, Cheng calls out the fact that these religious institutions may be forced to partner with organizations who “do not have perfect alignment of agendas” simply to access the funding they need.

Yet, Cheng believes success is possible if the bill is returned to its original form. “With the AMI at 80%, Seattle’s Black churches have a viable model that can be used as a national exemplar of self-sufficient development and a wonderful testament to the value of ‘patient capital’ where payoffs occur over an extended period of time.”

Now that the bill has been signed into law by Mayor Durkan, critics are hoping that the amended bill can be repealed and returned to its original form.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.