In the shadow of Asian Americans and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month and the midst of a dramatic rise in anti-Asian violence, I stumbled upon Tacoma’s Chinese Reconciliation Park. For me, parks are a place to exercise, sightsee, play, and come into contact with nature and sometimes history. I value them highly and see them as a place to escape the pace of the city. The Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Park certainly does all of that. However, instead of tackling the history of the land or long gone industry, it immortalizes a period of dark racial animus.

There have only been two waves of Chinese immigration to the United States. One that began in the 1970s and continues to this day, mostly defining how Chinese Americans are perceived by American society today. The other wave happened in the 1800s, characterized by hard labor and its suppression. The first wave mostly came from southeast China, sometimes fleeing war and famine, and lured by the promise of economic opportunity. They typically arrived in California first; eventually the then Territory of Washington would start to see an increase in Chinese laborers in the 1860s and 1870s. Tacoma may have seen its own real influx of Chinese migrants when Chinese were hired to work on the Northern Pacific Railroad line, the western terminus of which ended in the city at the time.

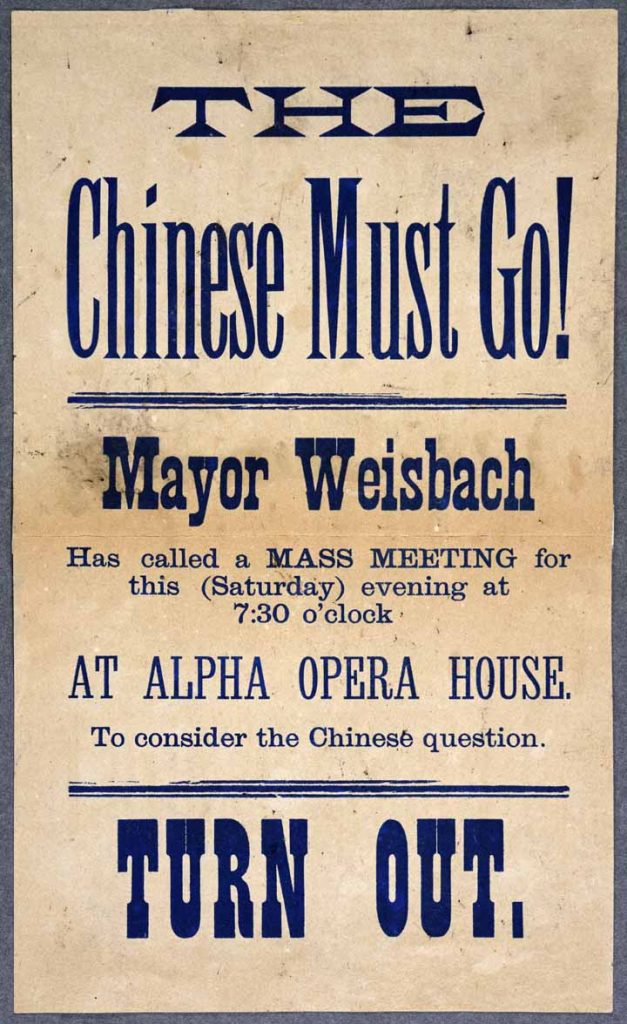

Stemming from mounting economic and racial tensions, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This law prohibited Chinese laborer migration, and made existing immigrants permanent aliens. It, in effect, was just a compromise to placate the White population and not provoke the Chinese government from banning trade. Counter to the wishes of the most extreme anti-Chinese population, existing Chinese laborer populations endured. That, paired with issues with enforcement, loopholes, and time limits, would cause anti-Chinese labor sentiments to boil over.

[In the Washington territory,] violence erupted first in Tacoma on 2 November. Unopposed by local authorities, a mob of nearly 300 whites, many of them armed, forced some 200 Chinese to leave in wagons. During a drive in pouring rain to Lake View Station, where the Chinese were to board a train to Portland, several Chinese suffered ill effects from exposure and died soon after.

From The role of federal military forces in domestic disorders, 1877-1945 by Clayton D. Laurie, Ronald H. Cole

“The next day some Tacomans ravaged Chinese businesses downtown and burned shops and lodgings that formed the Chinese settlement along the waterfront.” This expulsion and destruction in early November 1885 wasn’t spontaneous, there were anti-Chinese meetings, warnings and threats issued, and replacement of Chinese workers with workers of other ethnicities before the riots came. As a result of this expulsion and continued campaigning, no Chinese would return to Tacoma until the 1920s.

Remembering racial harm

The Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Park came about from a suggestion by Dr. David Murdoch to the City of Tacoma in response to a call for ideas about the development of the waterfront. Dr. Murdoch proposed a waterfront park with Chinese cultural motifs not far from Chinese settlements at the water’s edge before their expulsion and the properties’ destruction. An advisory committee of citizens that would become the Chinese Reconciliation Project Foundation formed in the fall of 1992, a year after the suggestion, and would form a vision of reconciliation that would educate the community about the incident and promote multicultural inclusiveness.

In 1993, funding for planning would be approved. Land transfer, groundbreaking, clean up, and construction would happen over a course of 17 years. Phase one and two of the project opened in late fall 2010. Phases three and four are ongoing work of the Foundation and City. Today, the park is appropriately situated by the water and the railroad that Chinese workers had helped build. The park is defined by the gleaming white bridge, open-walled pavilion, and symbolic carvings and pylons. Panels with snippets of the history of early Chinese and their expulsion dot the park.

This model of local action to integrate a past and public wrong into local green space is an interesting way to publicly address an incident and time of intentional racial animus. Given the long history of racial wrongs in the United States, there is plenty to draw up to inspire parks amenities and programming. Examining hyperlocal incidents centered around race can help us understand the environments and demographics that urbanites dwell in. Seattle, Bellingham, and other Washington settlements also had incidents. There’s likely no shortage of wrongs committed against other Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities in our local histories. Redlining comes to mind, its consequences still affecting how our neighborhoods look.

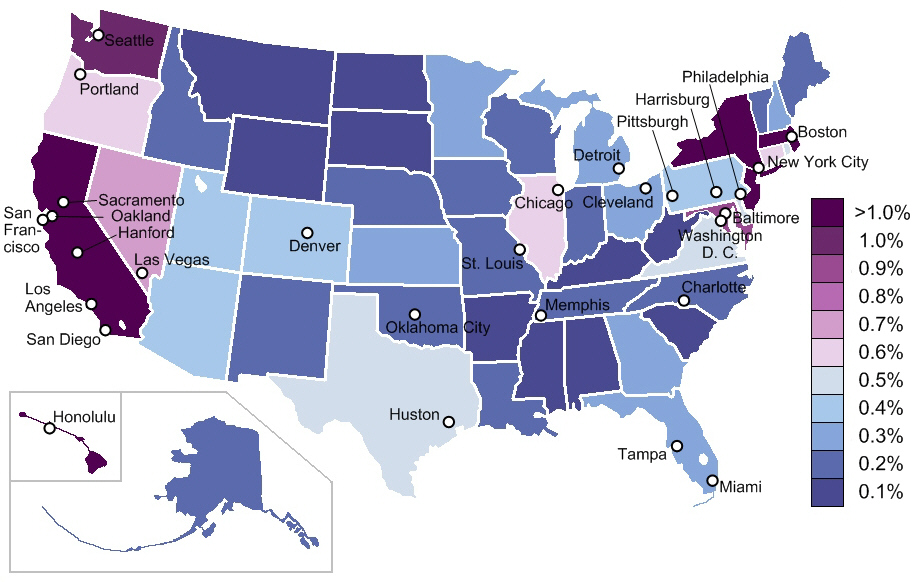

Today, Chinese Americans are among the smallest minorities in the states. Had Chinese been allowed to migrate and form families in the late 1800s and early 1900s, then we might be seeing a very different make up of our cities. The Chinese Exclusion Act was renewed and refreshed a few times, and would not be repealed until the 1940s. Even then immigration was limited, and all of these policies restricted and even shrank the Chinese American population over decades.

It would also be remiss of me to not mention the drastically different light that Chinese Americans are seen in by American society. Before, Chinese Americans migrants were typically unskilled laborers, as the migrants were of peasant castes. Changes in immigration law, which relegalized Chinese immigration in the mid-1900s and decreased restrictions on non-European immigration, prioritized skilled and highly sought after professionals and their families, creating the generally prosperous Asian American alcoves within today’s America. Many misinterpret this migration pattern as evidence supporting the myth of a model minority.

Planning parks with our history in mind

Parks already often give us the natural history of the lands we inhabit today, and teach us about how we are shaped to this day. It wouldn’t be much of a further step to provide the context of local racial incidents and policies that shade how our communities appear today. Perhaps it might be appropriate for park planning policies of our localities to consider local racial histories to grant their residents a whole picture of their past. It’s also an opportunity for cities to fund racial justice programs to work with local communities to create interesting and diverse green space on our public lands. Shaping green spaces to match the history of our city’s history seems appropriate to me.

These early Chinese laborers helped build the cities we live in now. They help us recognize the pattern of immigration and where our immigrant populations are now. I don’t think monuments to racial wrongs need to stand out, just having the park with some occasional cultural programming will bring attention to the history and lessons learned and learning. Clearly, there’s more to learn considering that AAPI communities also a whole are victim to rising anti-Asian violence when perpetrators are supposedly emboldened by pandemic scapegoating of a single nation and not a continent.

Building spaces that reflect the disenfranchised who helped build our cities should be a consideration by local government. Seattle Parks and Recreation seems to already be heading in this direction, as the 2020-2032 strategic plan for the agency heavily emphasizes their Pathway to Equity — a roadmap for the department to help meet Seattle’s racial equity goals. The agency is developing plans to integrate this kind of thinking into its processes and planning. Perhaps they could take a closer look at their much more bloody and dramatic anti-Chinese riots in 1886. Other cities like Bellevue have older planning documents for their parks, which only hint at equity and race. By the time their parks levies go up renewal — 2028 for Bellevue — I’d hope that their planning would entertain the idea of integrating racial equity into their spending programs.

Our parks are Jacks of all trades. Pairing racial history with other attractive amenities in our parks would add an extra dimension that acknowledges how our cities came to where they are today and where they’re headed. Our cities and parks departments should be able find past wrongs to acknowledge, without the need for the public to alert them to horrendous past wrongs. If you want to see more projects like the Tacoma Chinese Reconciliation Park, let your local representatives and your parks department know.

Shaun Kuo is a junior editor at The Urbanist and a recent graduate from the UW Tacoma Master of Arts in Community Planning. He is a urban planner at the Puget Sound Regional Council and a Seattle native that has lived in Wallingford, Northgate, and Lake Forest Park. He enjoys exploring the city by bus and foot.